- Submissions

Full Text

Research in Pediatrics & Neonatology

Unusual Location of a Gastric Perforation Due to a Huge Trichobezoar

D Hanine1,2*, B Rouijel1,2, L El Aqqaoui1,2, H Oubejja1,2, H Zerhouni1,2, M Erraji1,2 and F Ettayebi1,2

1Pediatric Surgery Emergencies Department, Children’s Hospital of Rabat, Morocco

2Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, Mohammed V University Rabat, Morocco

*Corresponding author:D Hanine, Pediatric Surgery Emergencies Department, Children’s Hospital of Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, Mohammed V University Rabat, Morocco

Submission: April 01, 2021 Published: April 29, 2021

ISSN: 2577-9200 Volume5 Issue4

Abstract

Trichobezoar is defined by the presence of an intragastric foreign body formed by hair or textile fibers. It is a rare condition that usually occurs in adolescents with mental health problems. The clinical symptoms are very varied and the diagnosis is often suspected on radiology and endoscopy, but sometimes certain complications such as peritonitis can be revealing. The treatment associates surgical and psychological care. We report the observation of a 14-year-old girl hospitalized with acute generalized peritonitis, clinical and radiological investigations concluded in a Trichobezoar complicated by gastric perforation. The treatment was surgical with pre and post-operative resuscitation. The evolution was favorable thereafter with a child psychiatric follow-up for the young adolescent. At the end of this observation, we highlight the possible complications of Trichobezoar and their management.

Keywords: Trichobezoar; Bezoar; Gastric perforation

Introduction

The term bezoar refers to various foreign bodies found in the gastrointestinal tract. Most are formed in the stomach by the accumulation of non-digestible substances, such as certain plant fibers (phytobezoar), hair (trichobezoar), concentrated dairy products (lactobezoar), more rarely certain drugs (pharmacobezoar) [1]. Trichobezoars usually result from the accumulation of hair, but, in rare cases, it can be papier-mâché, wool from carpets or clothing [1]. Although rare, but not exceptional; the trichobezoar usually affects children or young adolescents with mental health problems [2]. Its clinical symptoms are very varied, ranging from simple epigastralgia to a complete occlusive syndrome complicated by digestive perforation which can be fatal. The diagnosis is often suspected on radiology and endoscopy. The treatment is essentially surgical associated with psychological care. This work consists of a review of the literature on the trichobezoar in children, with a brief presentation and some reflections concerning the management of this condition.

Materials & Methods

Our study was done in January 2020 at the pediatric surgery emergencies department at

the Children’s Hospital of Rabat, the case studied is a 14-year-old girl brought by her parents

in an acute abdomen chart.

Having as a history, chronic epigastralgia with retrosternal pain. The history of the disease

was characterized by the onset one week earlier of acute abdominal pain with vomiting and

fever. Clinical examination showed a teenage girl in poor general condition, fever at 39° with

a septic face. Abdominal palpation revealed a mass of the left hypochondrium and left flank

extending beyond the midline with generalized abdominal defense.

The physical examination found also a slight alopecia of the scalp. The clinical diagnosis

of acute generalized peritonitis was retained. X-ray examinations were performed to

support the etiological diagnosis. An abdominal X-ray was performed showing an enormous

pneumoperitoneum with probable mass pushing back the transverse colon and the digestive

loops at the bottom (Figure 1). An abdominal ultrasound showed a peritoneal effusion of great

abundance without objectifying mass. After stabilizing the patient preoperative resuscitation,

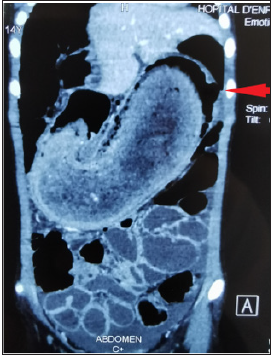

a CT scan was performed for orientation before surgical exploration (Figure 2).

Figure 1:Thoracoabdominal X-ray showing a huge pneumoperitoneum with backflow of the intestines at the bottom.

Figure 2:CT image showing the gastric trichobezoard with a perforation in the fundus (arrow).

This CT revealed an enormous intragastric mass extending to the pylorus with a perforation at the level of the Fundus (Figure 2) and a peritoneal effusion of great abundance. The supraumbilical midline laparotomy revealed a huge stomach that has been pulled out of the abdomen (Figure 3). After Gastrotomy, a large J-shaped Trichobezoar was removed which had the shape of the stomach (Figure 4). After abundant washing, an ulcerative perforation was found in the gastric Fundus with several false membranes around (Figure 5). We delimited the edges with suture in 2 planes as well as a suture of the gastrotomy in 2 planes. The postoperative followup was simple, marked by an exclusively parenteral diet for 5 days with resumption of transit and progressive enteral feeding. The short and long term course was good. Child psychiatric care was instituted for our young patient.

Figure 3: Surgical exploration showing a huge gastric mass.

Figure 4:Trichobezoard after being removed.

Figure 5:Trichobezoard after being removed.

Discussion

Trichobezoar is a rare condition, and in children it accounts

for 0.15% of gastrointestinal foreign bodies. The female sex is the

most affected (90% of cases) and the age of onset is in 80% of

cases less than 30 years, with a peak incidence between ten and

19 years [3], this was the case of our patient. It is important to

note that environmental and psychological factors can constitute

a predisposing ground for the development of Trichobezoars. The

gastric localization is the most frequent, the curls of hair thus

ingested are caught by the gastric mucosa to which they attach and

form a more or less complex tangle, a kind of wire mesh at the level

of which the food aggregates, forming a mass compact intimately

attached to the gastric wall. The trichobezoar thus formed can

spread to the small intestine, sometimes arriving at the last ileal

loop, or even in the transverse colon, thus producing Rapunzel

syndrome [4,5]. In our patient, it is a trichobezoar involving the

stomach and the first portion of the duodenum. This condition

can remain asymptomatic for a long time, which explains the

delay in diagnosis which can go up to several years. The clinical

symptoms are various and nonspecific [6]. It can range from simple

epigastralgia to a complete occlusive syndrome complicated by

digestive perforation which can be fatal.

The most frequent digestive disorders are abdominal pain

mainly epigastric, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, peptic

esophagitis and sometimes bad breath due to food putrefaction,

anorexia and weight loss can sometimes be the major clinical

element. It can be revealed immediately by acute complications;

such as gastrointestinal bleeding, acute bowel obstruction,

gastrointestinal perforation, or acute pancreatitis attributed

to obstruction of the ampulla of Vater by prolongation of the

trichobezoar or reactive edema, cholestatic jaundice, gastric ulcer

or duodenal and rarely volvulus of the large intestine [4].

In our patient, it was a gastric ulcer perforation in a trichobezoar,

thus complicating a generalized peritonitis.

The clinical examination, apart from the complications, finds

an abdominal mass located most often at the level of the left

hypochondrium and/or the epigastrium which should not be

missing in the diagnosis [7].

The discovery of a localized alopecia patch, of a mechanical

nature, is a major sign of orientation and should lead to a search

for trichophagia. Once the diagnosis of trichobezoar is made,

paraclinical investigations are necessary, whether radiological or

endoscopic. Esogastroduodenal fibroscopy (OGDF) confirms the

diagnosis by visualizing tangled hair generally green or dark green

in color, altered from normal, due to the chemical effect of gastric

acidity [8].In the giant trichobezoar, the fibroscopy is insufficient,

it does not make it possible to evaluate the extension at the level

of the jejuno-ileal loops, in these cases, the imaging finds all its

interest. The trichobezoar appears on Computed Tomography (CT)

as a mass of variable, heterogeneous volume, occupying almost the

entire gastric lumen and consisting of a multitude of concentric

circles of different densities distributed in onion bulbs.

Two pathognomonic and constant signs are the presence of

tiny air bubbles dispersed within the mass and the absence of any

attachment of the mass to the gastric wall [1,4]. The therapeutic

management depends on the size and the presence or absence of

complications, but remains surgical, by laparoscopy or laparotomy

[7-9]. The extraction of trichobezoar by gastrotomy is the reference

technique. Rarely, there will be a need to perform an enterotomy for

very extensive forms. The fact of performing a gastrostomy remains

controversial according to the authors, depending on experience

and the presence of complications. Psychiatric care, based on

behavioral therapy, parental education and medical treatment,

must often be instituted in these children.

Conclusion

Trichobezoar is a rare condition that usually occurs in adolescents with mental health problems. The clinical symptoms are very varied. The diagnosis is suspected due to the association of alopecia, trichomania and digestive disorder and its confirmation is based on data from oesogastro-duodenal fibroscopy and imaging (especially computed tomography) which thus guides therapeutic management. In addition to surgery, psychological care is an essential part of the treatment and especially the prevention of recurrences and complications.

References

- Aarje AL, Elhattabi K, Lefryekh R, Fadil A, Khaiz D, et al. (2006) Gastroduodenal and small intestine trichobezoar. Presse Med 45(2): 265-269.

- Roche C, Guye E, Coinde E, Galambrun C, Glastre C, et al. (2005) Five cases of trichobezoars in children. Arch Pediatr 12(11): 1608-1612.

- Ziadi T, En-nafaa I, Lamsiah T, Abilkacem EH, et al. (2011) Epigastric mass. Rev Med Interne 32(7): 445-446.

- Alouini R, Allani M, Arfaoui D, Arbi N, Graiess KT (2005) Duodenojejunal trichobezoar. Presse Med 34(16 Pt 1): 1178-1179.

- Duncan ND, Aitken R, Venugopal S, West W, Carpenter R (1994) The Rapunzel syndrome-report of a case and review of the literature. West Indian Med J 43(2): 63-65.

- Moujahid M, Ziadi T, Ennafe I, Kechma H, Ouzzad O, et al. (2011) A case of gastric trichobezoar. Pan Afr Med J 9: 19.

- Hafsa C, Golli M, Mekki M, Kriaa S, Belguith M, et al. (2005) Giant trichobezoard in children. Place of ultrasound and oesogastroduodenal transit. Journal of Pediatrics and Childcare 18(1): 28-32.

- Ousadden A, Mazaz K, Mellouki I, Taleb KA (2004) Gastric trichobezoar: An observation. Annals of Surgery 129(4): 237-240.

- Anoop D, Raza MA, Tiwari R (2016) Gastric trichobezoar with rapunzel syndrome: A case report. J Clin Diagn Res 10(2): PD10-PD11.

© 2021 D Hanine. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)