- Submissions

Full Text

Research in Pediatrics & Neonatology

Rapunzel Syndrome: An Unusual Onset Case Report

Sergio Manieri1*, Maria P Mirauda1, Carmela Colangelo1, Rosa Lapolla1, Luciana Romaniello1, Donatello Salvatore1 and Paolo Caiazzo2

1Department of Pediatrics, San Carlo Hospital, Potenza, Italy

2Pediatric surgery unit, San Carlo Hospital, Potenza, Italy

*Corresponding author: Sergio Manieri, Department of Pediatrics, San Carlo Hospital, Potenza, Italy

Submission: February 11, 2021 Published: February 24, 2021

ISSN: 2577-9200 Volume5 Issue3

Abstract

Bezoar is an accumulation of organic substances in the gastrointestinal tract. This condition is extremely rare, their incidence in the pediatric population is unknown. Bezoars usually occur in females, adolescents, and children with psychiatric or neurological disorders. Trichobezoar refers to the accumulation of hair usually in the stomach and even beyond it (Rapunzel syndrome). We present the clinical case of a schoolage female patient who started with neurological symptoms (headache, syncope) and then developed gastrointestinal symptoms. Only later was clarified a history of bullying at school and consequent anxious behaviors (trichotillomania and trichophagia). It’s very important a thorough medical history, especially in patients with Trichobezoar, to highlight psychological disorders that can cause trichotillomania and trichophagia.

Keywords: Trichobezoar; Trichotillomania; Trichofagia; Laparoscopy

Introduction

Bezoar is an accumulation of exogenous matter in the stomach or intestine. Rapunzel syndrome refers to a trichobezoar that extends from the stomach into the entire small bowel [1]. Bezoars are classified on the basis of their composition [2]. Trichobezoars are composed of the patient’s own hair. Phytobezoars are composed of a combination of plant and animal material. Trichophytobezoars are mix composition. It’s defined Orthobezoar when mineral salt are deposited on a nucleous of animal or vegetable. Lactobezoars were previously found most often in premature infants and may be attributed to the high casein or calcium content of some premature formulas. Shallowed chewing gum may occasionally lead to bezoars. This condition is extremely rare, their incidence in the pediatric population is unknown [3]. Most bezoars have been found in females with underlying personality problems or neurologically impaired individuals. About 70% of patients with trichobezoar intestinal obstructive syndrome are women under age 20 years [4]. Bezoars can be fatal because they can cause gastric and bowel perforation, peritonitis, bleeding, or ischemic to necrotic changes of the gut [5]. Patients diagnosed with a bezoar usually are asymptomatic for many years [6]. Some bezoars are found incidentally with imaging, where they appear as masses or filling defects on abdominal radiographs and computed tomography (CT) scans. Therefore, a thorough medical history is important, especially in patients with Trichobezoar, to highlight psychological disorders that can cause trichotillomania and trichophagia. In fact, about 6% of patients with Tricotillomania develop a trichobezoar [5]. Diagnosis can be established by an upper endoscopy with extraction sampling to determine the composition or extract the whole bezoar in fragments if it is only in the stomach and/or proximal bowel. Although endoscopy is the preferred diagnostic study to differentiate bezoars, but only a few cases in the literature describe the complete endoscopic removal of a trichobezoar after mechanical or chemical fragmentation, and these cases refer exclusively to pediatric patients in whom presumably the total foreign body mass was easier to handle [7]. Conventional laparotomy is the treatment of choice for trichobezoar with satellite fragments beyond the stomach or extending into the small bowel as in Rapunzel syndrome [1-5].

Case Report

We present the case of a trichobezoar intestinal obstructive

syndrome in a 12-year-old girl. The girl was hospitalized for

recurrent syncopal episodes, which started a few months ago,

some of which with doubtful loss of consciousness. In addition,

frequent headache episodes were reported for about 3 years, well

responsive to paracetamol. The medical history did not highlight

family pathologies, while the pathological history showed the

presence of hepatic hemartoma, diagnosed at the age of 2, for which

periodic ultrasound examinations are performed, and an episode of

Schonlein-Henoch purpura at the age 5 years old.

Physical examination revealed a palpable tumor within the

epigastrium, initially interpreted as referable to hepatic hemartoma,

for which we planned a control abdominal ultrasound. During the

hospitalization, several tests were performed including blood

biochemical examination, routine electrocardiogram, dynamic

electrocardiogram, echocardiography, vestibular examination, eye

examination, electroencephalogram, head magnetic resonance

imaging (RMI), excluding the organic disease of nervous system

and circulatory system. All tests were substantially normal.

Subsequently, in light of all this, psychological consultation was also

performed suspecting psychological involvement, which detected

a condition of psychological distress due to anxiety disorder, for

which child neuropsychiatric consultation was planned.

In the meantime, a few days after admission, another abdomen

ultrasound was performed which showed a mass in the stomach

that was not well interpretable, for which a CT of the abdomen was

performed which showed the presence of solid tissue in the epigastric

area not well defined, extending for about 6 cm, with no evident

cleavage plane towards the head of the pancreas, the gastric antrum

(apparently infiltrated) and the duodenal C. For further study, MRI

of the abdomen was performed which interpreted the abdominal

lesion as likely pancreatic nature (annular pancreas?). In the

meantime, the symptoms had changed as the girl began to present

abdominal pain and vomiting and appeared particularly dejected.

Apart from hypochromic and microcytic anemia, laboratory test

results were unremarkable. Therefore a new ultrasound evaluation

was carried out which this time highlighted, in the context of the

gastric lumen, the presence of a solid mass, extended for about

13cm from the gastric body to the duodenum. The subsequent

barium abdominal X-ray raised the suspicion of trichobezoar, later

confirmed by upper gastrointestinal tract endoscopy which showed

a large trichobezoar occluding the stomach from the fundus to the

antrum with extension into the duodenum and a peptic ulcers was

detected in the area of Vater’s papilla underneath the attachment

base of the hair mass as a result of pressure necrosis (Figure 1).

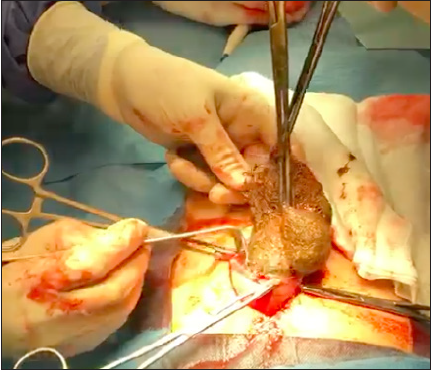

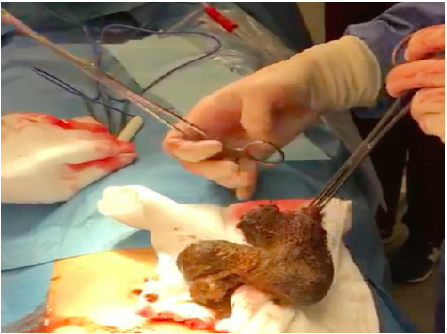

Repeated attempts at fragmentation and extraction of the mass

have been made, but without success, for which a gastrostomy and

removal of the trichobezoar were used (Figures 2 & 3). The postsurgery

course was regular, without complications. Subsequently,

as planned, child neuropsychiatric consultation was performed,

from which a condition of trichotillomania emerged for about 2

years, probably linked to bullying at school and an anxious state.

Currently, the girl is in good health in the absence of symptoms

referable to relapse and is followed up by the neuropsychiatrist.

Figure 1:Endoscopic view of the trichobezoar.

Figure 2:Surgical breach with the trichobezoar.

Figure 3:Intraoperative view of the trichobezoar.

Discussion

Bezoars are masses of partially or totally indigestible material,

that is, unassailable by gastrointestinal secretions, which generally

gather in the stomach and can cause various dyspeptic disorders

up to gastrointestinal occlusion. Trichobezoars are clusters of

undigested hair, mucus and fats. They are responsible for Rapunzel

Syndrome, named after the character created by the brothers

Grimm’s imagination, a rare medical condition in which the hair,

which people ingest, forms a tangled mass that remains trapped

in the stomach and extends to the small intestine. A trichobezoar

occurs mainly in association with a psychiatric disorder affecting

usually young women, having the tendency of pulling out their

own hair (trichotillomania) and eating it (trichophagia). Affected

people are often asymptomatic. Symptoms and signs are related

to the mass that progressively occupies the space of the gastric

lumen and its obstacle to gastric function. Most common symptoms

are abdominal pain, vomiting, and gastrointestinal bleeding from

asymptomatic anemia to hematemesis [8]. Moreover, patients can

complain early satiety, obstruction, peritonitis, intussusception and

weight loss [9]. A few cases present with obstructive jaundice [10],

pancreatitis [11,12], appendicitis [13] and gut perforation [14,15].

Abdominal examination typically reveals an upper abdominal mass

(Lamerton’s sign) [9].

The Gold standard of diagnosis of trichobezoars is upper

gastrointestinal endoscopy [16]. Others modalities are of additional

help. The upper abdomen CT is reported to be more effective than

ultrasound and barium meal in revealing concomitant gastric and

intestinal bezoars, and it also has proven accuracy in determining

the level and degree of intestinal obstruction [17]. However, upper

endoscopy is the most sensitive examination for diagnosis and also

plays a fundamental therapeutic role. Treatment of trichobezoars

aims to completely remove the mass and prevent recurrence.

Laparotomy is still the treatment of choice for large trichobezoars

because of its advantages which include the simplicity of the

procedure, less time required and feasibility to examination all the

bowel for satellite lesions [18]. However, laparoscopic intervention

seems to be gaining ground over open surgical operation and there

are several cases reporting the laparoscopic removal of extremely

long and large trichobezoars [19]. Recurrence has been reported

owing to improperly treated psychiatric conditions and missed

follow-up [20].

Conclusion

The diagnosis of trichobezoar is easy after detailed enquiry of medical history, paying close attention to the risk factors (trichotillomania, trichophagia, alopecia). In our case report the initial diagnosis was oriented towards a neurological pathology (headache, syncope) and only later did neuropsychiatric disorders emerge. Therefore, it is very important to pay attention to the psychological aspects, to avoid diagnostic delays or misdiagnoses. There are no standardized techniques for treatment. In the case of small sized trichobezoars, endoscopic treatment may be useful, on the contrary in the case of large, non-fragmentable or molded trichibezoars, the surgical approach is the treatment of choice.

References

- Atul M, Jainty J (2018) Trichobezoar requiring surgical intervention. JAAPA 31(9): 32-34.

- Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB (2004) Nelson textbook of pediatrics. (17th edn), Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia, USA, p.1244.

- Azevedo S, Lopes J, Marques A, Mourato P, Freitas L (2011) Successful endoscopic resolution of a large gastric bezoar in a child. World J Gastrointest Endosc 3(6): 129-132.

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (5th edn), American Psychiatric Association, Washington DC, USA.

- Wyllie R, Hyams JS, Kay M (2011) Pediatric gastrointestinal and liver disease. (5th edn), Elsevier Saunders; Philadelphia, USA, p. 340-343.

- Gorter RR, Kneepkens CM, Mattens EC, Aronson DC, Heji HA (2010) Management of trichobezoar: Case report and literature review. Pediatr Surg Int 26(5): 457-463.

- Benatta MA (2015) Endoscopic retrieval of gastric trichobezoar after fragmentation with electrocautery using polypectomy snare and argon plasma coagulation in a pediatric patient. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 4(3): 251-253.

- Iwamuro M, Okada H, Matsueda K, Inaba T, Kusumoto C, et al. (2015) Review of the diagnosis and management of gastrointestinal bezoars. World J Gastrointest Endosc 7(4): 336-345.

- Naik S, Gupta V, Naik S, Rangole A, Chaudhary AK, et al. (2007) Rapunzel syndrome reviewed and redefined. Dig Surg 24(3): 157-161.

- Chogle A, Bonilla S, Browne M, Madonna MB, Parsons W, et al. (2010) Rapunzel syndrome: A rare cause of biliary obstruction. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 51(4): 522-523.

- Kohler JE, Millie M, Neuger E (2012) Trichobezoar causing pancreatitis: First reported case of rapunzel syndrome in a boy in North America. J Pediatr Surg 47(3): e17-e19.

- Jalali BK, Bingöl A, Reyad A (2016) Laparoscopic management of acute pancreatitis secondary to Rapunzel syndrome. Case Rep Surg 2016: 7638504.

- Kumar TR, Rao GC (2014) Isolated Rapunzel tail presenting as acute appendicitis. Indian J Pediatr 81(11): 1260.

- Koc O, Yildiz FD, Narci A, Sen TA (2009) An unusual cause of gastric perforation in childhood: Trichobezoar (Rapunzel syndrome). A case report. Eur J Pediatr 168(4): 495-497.

- Parakh JS, McAvoy A, Corless DJ (2016) Rapunzel syndrome resulting in gastric perforation. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 98(1): e6-e7.

- Gonuguntla V, Joshi DD (2009) Rapunzel syndrome: A comprehensive review of an unusual case of trichobezoar. Clin Med Res 7(3): 99-102.

- Ripolles T, Aguayo JG, Martinez MJ, Gil P (2001) Gastrointestinal bezoars: Sonographic and CT characteristics. AJR Am J Roentgenol 177(1): 65-69.

- Middleton E, Macksey LF, Phillips JD (2012) Rapunzel syndrome in a paediatric patient: A case report. AANA J 80(2): 115-119.

- Jatal SN, Jamadar NP, Jadhav B, Siddiqui S, Ingle SB (2015) Extremely unusual case of gastrointestinal trichobezoar. World J Clin Cases 3(5): 466-469.

- Tiwary SK, Kumar S, Khanna R, Khanna AK (2011) Recurrent rapunzel syndrome. Singapore Med J 52(6): e128-130.

© 2021 Sergio Manieri. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)