- Submissions

Full Text

Research in Pediatrics & Neonatology

Diagnosis of Acquired Hemophilia A Must be Considered in Childhood: A Case Report

Harroche A1*, Lasne D2,3, Bally C1, Pascreau T2,3, Rothschild R1 and Borgel D2,3

1Hemophilia Care Center, Hematology Unit, Hôpital Universitaire Necker Enfants-Malades, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, France.

2Service dHématologie Biologique, Hôpital Universitaire Necker Enfants-Malades, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, France.

3UMR INSERM 1176, Hôpital Bicêtre, Le Kremlin-Bicêtre, France

*Corresponding author:Harroche Annie, Centre de traitement de l’Hémophilie, Service d’Hématologie Clinique, Hôpital Necker, France

Submission: November 11, 2019; Published: December 02, 2019

ISSN: 2577-9200 Volume4 Issue1

Abstract

Acquired Hemophilia A is a very rare disease in children but may be life-threatening. We report the case of a 5-year-old child, without any bleeding history. He presented a severe bleeding episode after a circumcision. The blood loss was important, with a hemoglobin rate at 54g/L, requiring a transfusion. The first biological assessment of hemostasis lead to the suspected diagnosis of congenital hemophilia (FVIII=4%), but factor VIII infusions were inefficient. Identification of a specific inhibitor against factor VIII rectified the diagnosis: it was an acquired hemophilia A. No underlying infectious, autoimmune or neoplastic disease was found. Interestingly, he has family history of immune disease: his brother has a juvenile arthritis and his father a Sjogren syndrome.

Clinical evolution was favorable after treatment by recombinant activated factor VII (Novoseven®). Afterwards, he has two bleeding episodes: a large post-venous puncture hematoma, and a post-traumatic hemarthrosis of the knee, efficiently treated by Novoseven®. An immunosuppressive treatment started then: he received a first line therapy of corticoids without any effect on the inhibitor level. A second line therapy with rituximab was attempted, with a greater efficacy. The inhibitor level is now below 1 BU/ml, and the factor VIII level is 120%. This case highlights the difficulties of diagnosing acquired hemophilia A in childhood. Due to its rarity, this condition was first not recognized. Concerning immunosuppressive therapy, this case is the second case of the pediatric literature in this indication that proves efficacy of rituximab.

Keywords: Acquired hemophilia A; Childhood; Rituximab; Post-operative hemorrhage; Hemarthrosis; Diagnosis

Case Report

Acquired hemophilia A (AHA) is a very rare yet potentially life-threatening disease, especially in children. We have reported the case of a 5-year-old Senegalese boy who underwent circumcision. The patient had an asymptomatic sickle cell trait, along with susceptibility to allergies presenting as cow’s milk protein allergy, asthma, and eczema. He had no history of bleeding, and was not receiving any treatment prior to the circumcision. No prior infection was reported. His parents denied consanguinity, and there was no familial bleeding history, although his father reported prior episodes of epistaxis and gum bruising. The father also suffered from idiopathic Sjögren’s syndrome, whereas his mother had no particular medical history. Additionally, his paternal half-brother exhibited juvenile idiopathic arthritis. As the patient had been walking since he was 14 months old and had neither personal nor familial bleeding history, no hemostasis exploration was performed prior to surgery [1]. The circumcision, carried out in a private clinic, was culturally motivated. As there were no perioperative complications, the patient was promptly discharged. Bleeding from the surgical site began 12 hours following the intervention when the patient was already at home. Due to the bleeding severity, the boy was rapidly transferred to the nearest hospital, and laboratory tests were performed. Hemostasis exploration revealed a prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) (ratio: 3.72), whereas prothrombin time and fibrinogen level were normal (ratio 1.03 and 4g/L, respectively).

The blood count showed significantly decreased hemoglobin levels (Hb: 54g/L), possibly secondary to the active hemorrhage, whereas platelet and white blood cell counts were normal. The patient had not previously undergone blood cell counting. Based on these preliminary findings, a coagulation defect was suspected, and the patient was transferred to our hospital, a national reference center for hemorrhagic diseases, in order to receive optimal management. Upon arrival (Day 1), the boy immediately received one red blood cell unit (15ml/Kg) resulting in hemoglobin levels increasing up to 91g/L. APTT prolongation was confirmed (ratio 2.04) and further explored, revealing low FVIII levels of 4% along with normal FIX and FXI levels (129% and 120%, respectively). Before obtaining these results and while waiting for deficient factor identification, the patient was treated using a bypassing agent, namely the recombinant activated factor VII (rFVIIa, NovoSeven®, by NovoNordisk®) that stopped the bleeding. The next morning, on Day 2, a second blood sample revealed FVIII levels below 1%. The von Willebrand factor was found at 251%, thereby excluding von Willebrand disease (vWD). Given this context, congenital severe hemophilia A was diagnosed, and the boy’s treatment was switched to 45IU/Kg of recombinant factor VIII (FVIII, Refacto®, Pfizer), infused every eight hours, aimed to increase FVIII to 60-80% as residual rate. This treatment proved inefficient since bleeding started again 12h after the first recombinant FVIII had been administered. Biological response to treatment was evaluated at this stage, with FVIII still below1%, despite administering curative doses of recombinant FVIII. Owing to the absence of clinical and biological response, the given diagnosis of congenital severe hemophilia A was reassessed. In particular, the patient’s first blood sample taken prior to FVIII supplementation was re-tested for detection of anti-FVIII inhibitory antibodies using mixing studies. This new exploration revealed the presence of a functional inhibitor, though the patient had never received plasma derived or recombinant FVIII prior to this episode. Inhibitor titration was performed using the Bethesda assay, resulting in a high positive titer (26BU/mL). Considering this context, the main hypothesis then suggested was that of acquired hemophilia A (AHA) with the development of autoantibodies against FVIII. To support this hypothesis and dismiss a severe congenital hemophilia A, complete FVIII gene sequencing was performed, with no mutation detected. Based on this new diagnosis, on Day 3, the boy’s treatment was switched to recombinant FVIIa (NovoSeven®), 150μg/Kg every three hours for 24h, which resulted in rapid bleeding control. Considering the favorable clinical evolution of the hemorrhagic episode, recombinant FVIIa was rapidly spaced out (150μg/Kg every four hours for 24h, and then every six hours for 24h). The patient was discharged on Day 5 and then returned to the hospital every day for a daily rFVIIa infusion until complete healing.

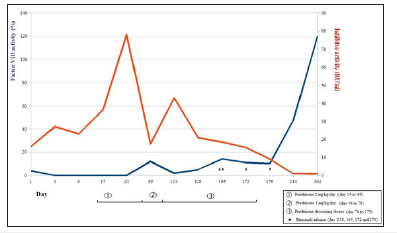

On Day 7, after vein puncture for NovoSeven® administration, the boy presented a significant and painful hematoma on his hand. He was then re-hospitalized and administered the same treatment, namely rFVIIa every 3 hours for 24h, which was then progressively spaced out. The boy was discharged after 4 days of treatment, with no further infusions required. Five days after he had been discharged, the patient exhibited a post-traumatic hemarthrosis of the right knee, was rehospitalized, and received the same rFVIIa treatment as before. Given the aim to obtain autoantibody production control, an immunosuppressive treatment was initiated on Day 15. The patient first received oral corticosteroids (prednisone) for 2 months, the first month at 2mg/Kg/day and second at 1mg/Kg/ day, followed by a progressive dose decrease during 3 months. This resulted in a partial inhibitor titer decrease, yet while decreasing prednisone, autoantibody production rate rose again. A secondline immunosuppressive treatment with MabThera® (rituximab, by Roche®, four weekly doses of 375mg/m2) was then initiated. As observed in Figure 1, after the four MabThera® treatments, there was a decrease in auto-antibody titers. The clinical outcome was favorable with no bleeding episodes noted since the beginning of the corticosteroid treatment. Finally, no underlying cause was found, although we tested for inflammatory, dysimmunitary, and neoplastic diseases, all tests resulting in negative results.This case highlights the difficulties of diagnosing AHA in childhood. Due to AHA’s rarity in childhood, this condition was first not recognized.

Figure 1:Progression curves for FVIII level and inhibitory activity, according different treatments.

Thus far, only 28 cases of acquired anti-FVIII inhibitor formation have been reported in children in the scientific literature [2]. In only four of the reported cases, the inhibitor against FVIII was detected in the context of post-operative bleeding, whereas in most of the other cases, autoantibody occurrence was revealed by either skin and mucosal bleeding or hematomas. This case calls attention to the need of excluding AHA in children with low FVIII levels. Given this scenario, mixing studies should be performed as soon as a low FVIII levels have been confirmed. In the reported case, several clinical data sources might in fact have suggested the clinical diagnosis of AHA. Firstly, it was the child’s first bleeding episode while he was already 5 years old at the moment of the diagnosis and had never before experienced soft tissue or joint bleeds, which are commonly observed symptoms in severe hemophilia when children learn to walk. The FVIII level, first established at 4%, was coherent with the absence of personal bleeding history, contrary to the <1% level found on Day 2. These FVIII level variations from one day to another would have been surprising for congenital hemophilia A, yet were retrospectively consistent with the AHA diagnosis. Secondly, the familial history could have caught our attention. However, the absence of familial bleeding history was non-contributory, since about one-third of congenital hemophilia originate from de novo mutations [3,4]. Nevertheless, the context of autoimmune disorders in both his father and half-brother was alerting, although we did not find any clinical nor biological arguments pleading for autoimmune disorders in our patient. In almost 55% of the reported acquired hemophilia cases in children [2], the autoantibody was shown to be associated with an underlying autoimmune disorder, infectious context, or antibiotic use.

None of these associated conditions were present in our case, rendering the disease presentation even more misleading. Concerning the treatment, our experience confirmed rituximab to be an effective treatment for AHA in children. This case is the second one of the pediatric literatures [5].

AHA treatment is currently guided by the 2015 consensus recommendations for adult patients [6-8]: corticosteroids as firstline treatment along with cyclophosphamide that may improve treatment efficiency. This first-line treatment has to be continued during at least 5 weeks before switching to second-line therapy. While intravenous immunoglobulin administration appears inefficient, spontaneous remissions may occur in 25% of untreated patients, especially during pregnancy [2,7]. Relapse is seen in up to 20% of cases occurring between one week to 14 months, which means that long-term follow-up is required. Concerning rituximab as second-line treatment, there is no published evidence that second-line rituximab is more efficient than first-line. Nevertheless, rituximab has been used as first-line therapy in certain cases, resulting in a lower relapse rate (1% of treated patients). Rituximab safety in children has been well-studied, especially for treating hematological malignancies and autoimmune disorders [9,10]. A rate of 37% adverse events was reported with both treatments, namely corticosteroids and rituximab [7]. Our patient exhibited no complications, and the inhibitor titer was recorded below 1BU/mL for the first time 1 year after corticosteroid therapy and 6 months after rituximab infusion. The inhibitor titer was for the first time negative (below 0.6UB/ml) 6 more months later and remained negative during the last three years. AHA diagnosis should be considered in children, especially those without bleeding history, while rituximab therapy may prove beneficial.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is important to note that acquired hemophilia is rare in children, but it is necessary to think about this diagnosis: our first hypothesis was a congenital hemophilia, and the first line treatment was thus not appropriate. Moreover, the therapeutic support must take into account the use of rituximab in case of corticosteroid treatment failure in children.

References

- Bonhomme F, Ajzenberg N, Schved JF, Molliex S, Samama CM, et al. (2013) Pre-interventional haemostatic assessment: guidelines from the french society of anaesthesia and intensive care. European Journal of Anaesthesiology 30(4): 142-162.

- Franchini M, Mannucci PM (2013) Acquired haemophilia A: a 2013 update. Thromb Haemost 110(6): 1114-1120.

- Kasper CK, Lin JC (2007) Prevalence of sporadic and familial haemophilia. Haemophilia 13(1): 90-92.

- Knoebl P, Marco P, Baudo F, Collins P, Huth Kuhne A, et al. (2012) Demographic and clinical data in acquired hemophilia A: results from the European Acquired Haemophilia Registry (EACH2). J Thromb Haemost 10(4): 622-631.

- Fletcher M, Crombet O, Morales Arias J (2014) Successful treatment of acquired hemophilia a with rituximab and steroids in a 5-year-old girl. Journal of pediatric hematology/oncology 36(2): e103-e104.

- Collins P, Baudo F, Huth Kuhne A, Ingerslev J, Kessler CM, et al, (2010) Consensus recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of acquired hemophilia A. BMC Research Notes 3: 161-168.

- Collins P, Baudo F, Knoebl P, Levesque H, Nemes L, et al. (2012) Immunosuppression for acquired hemophilia A: results from the European Acquired Haemophilia Registry (EACH2). Blood 120(1): 47-55.

- Collins PW (2012) Therapeutic challenges in acquired factor VIII deficiency. Hematology / the education program of the American society of hematology American society of hematology education program 2012: 369-374.

- Zhao Z, Liao G, Li Y, Zhou S, Zou H (2015) The efficacy and safety of rituximab in treating childhood refractory nephrotic syndrome: a meta-analysis. Scientific Reports 5: 8219.

- Olfat M, Silverman ED, Levy DM (2015) Rituximab therapy has a rapid and durable response for refractory cytopenia in childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 24(9): 966-972.

© 2019 Harroche Annie. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)