- Submissions

Full Text

Research in Pediatrics & Neonatology

Continuous Hand Hygiene Monitoring Associated with a Two-Year Elimination of Central Line Associated Bloodstream Infections in the NICU

Tarik Zahouani*, Zenaida Reyno, Suraiya Jahan, Lillian Diaz, Melba Talan, Ronald Bainbridge and Yekaterina Sitnitskaya

Department of Pediatrics, Lincoln Medical and Mental Health Center, USA

*Corresponding author: Tarik Zahouani, Department of Pediatrics, Lincoln Medical and Mental Health Center, New York, USA

Submission: June 08, 2018; Published: August 09, 2018

ISSN: 2576-9200 Volume2 Issue4

Abstract

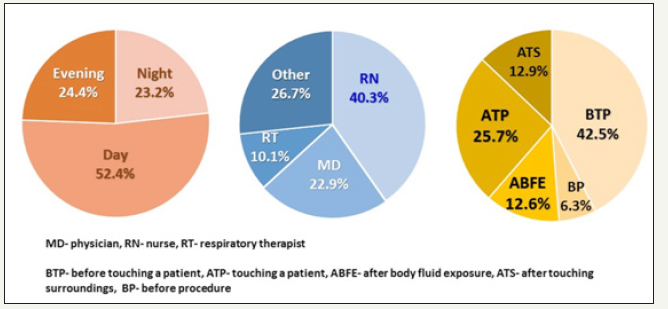

Hand Hygiene (HH) is the single most important method of preventing Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections (CLABSIs). We conducted a continuous 15 months long Performance Improvement project of HH monitoring in the NICU. Overt audit was conducted by trained unit staff, using modified World Health Organization Hand Hygiene Observation Tool. The data collected from October 2015 to December 2016 was entered into a departmental database. Of a total of 1466 observation, HH was observed 591, 40.3% times in nurses, 335, 22.9% times in resident and attending physicians, 148, 10.1% in Respiratory Therapists, and 392, 26.7% times in other ancillary staff. Most observations were conducted during the 0800- 1600day shift (768, 52.4%), followed by the 1600-0000 evening shift (358, 24.4%), and then by the 0000-0800night shift (340, 23.2%). HH before touching patient was observed most commonly. Overall HH compliance rate increased from the pre-project nadir of 63% to 99.9% during the project period.

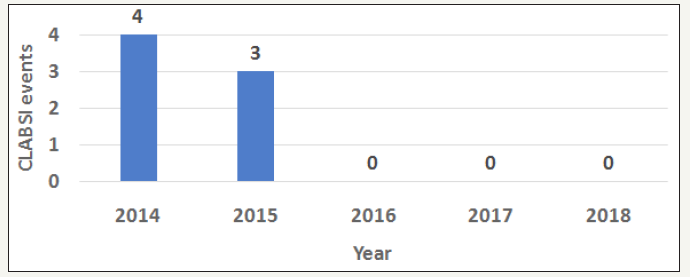

Only 4 fallouts were identified, all during the day shift. Of these, 3 fallouts were observed in nurses, and 1 in a resident physician. In each instance education was provided in real-time. The interim analysis was shared at monthly unit staff meetings. After the PI project was completed, HH was observed by Head/Charge Nurses and Infection control personnel. From January 2017 to January 2018 HH compliance rate in NICU remained at 100%. There were no CLABSI events for a total of 27 months. Our experience is consistent with previous reports suggesting that education and feedback are the most successful strategies in achieving high HH compliance. We believe that combining real time education with feedback is as important as routine sharing of performance indicators with the multidisciplinary unit team. A positive after-effect in the post PI project phase demonstrates a change in the safety culture of our NICU.

Keywords:Hand hygiene; Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infection (CLABSI); Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU)

Introduction

Hand hygiene (HH) is the cornerstone of prevention of Healthcare Associated Infection (HAI) [1]. Neonates are among the most vulnerable patient populations, however compliance with HH in the NICUs remains a struggle [2-7]. In the US current HH practices are regulated by the Association for Professionals in Infection Control (APIC) and epidemiology guidelines from 2015, which are in concordance with the “5 Moments for Hand Hygiene” approach introduced by the World Health Organization (WHO) [1].

There are multiple modalities for HH monitoring, from video surveillance to quantitation of hand sanitizer use by frequency per patient per day through electronic recording, or by volume per patient per day, to direct overt or covert monitoring by a hospital employee [8-15]. We share the experience of implementing a continuous 15 months HH monitoring project in our NICU using a modified WHO tool, and present an association between an increase in HH compliance rate and an absence of CLABSI events.

Setting and Methods

Our level III NICU has average of 350 admissions per year. The majority of catheter-days were related to the use of PICC lines. The unit is fully compliant with central line insertion and maintenance bundles, based on CDC recommendations [16], which are reflected in the institutional policy. In addition to spot checks by the Infection control personnel, compliance with CLABSI prevention bundle is monitored every shift by a Charge/Head Nurse, and recorded in individual patient’s check list. However, between 2013 and 2015, the CLABSI rate in the NICU was above the National Healthcare Safety Network benchmark (no clusters), and in June of 2015 the HH compliance rate in the unit reached a nadir of 63%.

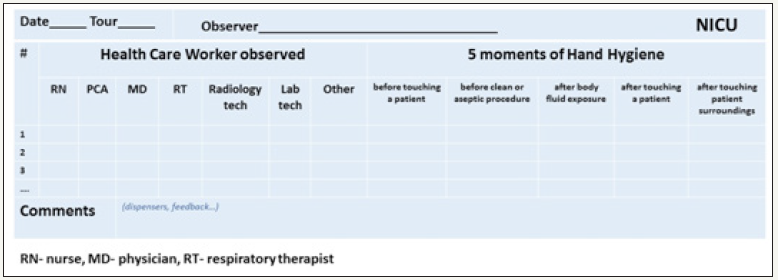

After comprehensive analysis of opportunities for improvement by a multidisciplinary team, the unit leadership developed a Performance Improvement (PI) project (Figure 1). The project was discussed and accepted by the entire NICU team. From October 2015 to December 2016 overt HH audit was conducted by trained unit staff. The training of observers was provided by the Infection Control Department. The observers used modified World Health Organization Hand Hygiene Observation Tool (Figure 2). The HH observation data was entered into the departmental database. Analysis was also conducted on CLABSI rates before and after implementation of the continuous HH monitoring, in conjunction with central line utilization. Feedback to the stakeholders was given individually in real time as needed, and to the unit staff on a monthly basis.

Figure 1:The performances improvement projects to increase compliances with HH in the NICU.

Figure 2:Hand hygiene observation tool.

Result

Of a total of 1466 observation, HH was observed 591, 40.3% times in nurses, 335, 22.9% times in physicians, 148, 10.1% in Respiratory Therapists, and 392, 26.7% times in other ancillary staff. Most observations were conducted during day shift (768, 52.4%), followed by night shift (358, 24.4%), and by evening shift (340, 23.2%). HH before touching patient was observed most commonly (Figure 3). Overall HH compliance rate increased from the pre-project nadir of 63% to 99.9%. Only 4 fallouts were identified, all during the day shift. Of these, 3 fallouts were observed in nurses, and 1 in a resident physician. In each instance a fallout feedback and education were provided in real-time. The interim analysis was shared at a monthly unit staff meeting. After the PI project was completed, HH in the unit was observed by Head/Charge Nurses and Infection control personnel. From January 2017 to January 2018HH compliance rate in NICU remained at 100%. There were no CLABSI events for a total of 27 months (Figure 4).

Figure 3:Observation of HH in the NICU by shift and discipline

Figure 4:CLABSI events in the NICU, January 2014-January 2018.

Discussion

Our experience is consistent with previous reports suggesting that education and feedback are the most successful strategies in achieving high HH compliance [10,17-19]. It appears that combining real time feedback with education is as important as routine sharing of performance indicators with the multidisciplinary unit team. We have demonstrated a positive after-effect in the post PI project phase: HH compliance rate in NICU remained at 100%. We believe that sustainability of compliance with HH reflects a change in the safety culture in our NICU. Zero CLABSI events for a total of 27 months has been a source of encouragement that has empowered the team.

Conclusion

We attribute our success to three points: First, unit team contribution to shaping the PI project and embracing it from the start. Second, feedback and education were individualized and given in real time. Finally, the staff members were motivated by zero CLABSI rate. We believe that this reflects a change in the safety culture of our NICU and is the most promising factor in sustaining compliance with HH.

References

- Guide to Hand Hygiene Programs for Infection Prevention (2015) Association for professionals in infection control and epidemiology. Printed in the United States of America First edition, Arlington, USA.

- Capretti MG, Sandri F, Tridapalli E, Galletti S, Petracci E, et al. (2008) Impact of a standardized hand hygiene program on the incidence of nosocomial infection in very low birth weight infants. Am J Infect Control 36(6): 430-435.

- Helder OK, Brug J, Looman CW, van Goudoever JB, Kornelisse RF (2010) The impact of an education program on hand hygiene compliance and nosocomial infection incidence in an urban neonatal intensive care unit: An intervention study with before and after comparison. Inter J Nurs Studie 47(10): 1245-1252.

- Wirtschafter DD, Pettit J, Kurtin P, Dalsey M, Chance K, et al. (2010) A state wide quality improvement collaborative to reduce neonatal central line-associated blood stream infections. J Perinatol 30(3): 170-181.

- Payne NR, Barry J, Berg W, Brasel DE, Hagen EA, et al. (2012) Sustained reduction in neonatal nosocomial infections through quality improvement efforts. Pediatrics 129: e165-e173.

- Ting JY, Goh VS, Osiovich H (2013) Reduction of central line-associated bloodstream infection rates in a neonatal intensive care unit after implementation of a multidisciplinary evidence-based quality improvement collaborative: A four-year surveillance. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 24(4): 185-190.

- Shepherd EG, Kelly TJ, Vinsel JA, Cunningham DJ, Keels E, et al. (2015) Significant reduction of central line associated bloodstream infections in a network of diverse neonatal nurseries. J Pediatr 167: 41-46.

- Raskind CH, Worley S, Vinski J, Goldfarb J (20017) Hand hygiene compliance rates after an educational intervention in a neonatal intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 28(9): 1096-1098.

- Mukerji A, Narciso J, Moore C, McGeer A, Kelly E, et al. (2013) An observational study of the hand hygiene initiative: a comparison of preintervention and postintervention outcomes. BMJ Open 3(5): e003018.

- Ofek Shlomai N, Raio S, Patole S (2015) Efficacy of interventions to improve hand hygiene compliance in neonatal units: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 34(5): 887-897.

- Haas JP, Larson EL (2007) Measurement of compliance with hand hygiene. J Hosp Infect 66(1): 6-14.

- Van den Hoogen A, Brouwer AJ, Verboon Maciolek MA, Gerards LJ, Fleer A, et al. (2011) Improvement of adherence to hand hygiene practice using a multimodal intervention program in a neonatal intensive care. J Nurs Care Qual 26(1): 22-29.

- Sakamoto F, Yamada H, Suzuki C, Sugiura H, Tokuda Y (2010) Increased use of alcohol-based hand sanitizers and successful eradication of methicillin- resistant Staphylococcus aureus from a neonatal intensive care unit: a multivariate time series analysis. Am J Infect Control 38(7): 529- 534.

- Helder OK, van Goudoever JB, Hop WC, Brug J, Kornelisse RF (2012) Hand disinfection in a neonatal intensive care unit: continuous electronic monitoring over a one-year period. BMC Infect Dis 12: 248.

- Alp E, Orhan T, Kürkcü CA, Ersoy S, McLaws ML (2015) The first six years of surveillance in pediatric and neonatal intensive care units in Turkey. Antimicrol Resis Infect Control 4: 34.

- O’Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, Dellinger EP, Garland J, et al. (2011) Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Clin Infect Dis 52(9): e162-e193.

- Toltzis P, Walsh M (2010) Recently tested strategies to reduce nosocomial infections in the neonatal intensive care unit. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 8(2): 235-242.

- Scheithauer S, Lemmen SW (2013) How can compliance with hand hygiene be improved in specialized areas of a university hospital? J Hosp Infect 83(Suppl 1): S17-S22.

- Kingston L, O’Connell NH, Dunne CP (2015) Hand hygiene-related clinical trials reported since 2010: A systematic review. J Hosp Infect 92(4): 309-320.

© 2018 Tarik Zahouani. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)