- Submissions

Full Text

Research in Pediatrics & Neonatology

Common Congenital Neck Masses in Childhood: A Review Article

Volkan Sarper Erikci1* and Tunç Özdemir2

1Department of Pediatric Surgery, Tepecik Training Hospital & Sağlik Bilimleri University, Turkey

2Department of Pediatric Surgery, Saglik Bilimleri University, Turkey

*Corresponding author: Volkan Sarper Erikci, Department of Pediatric Surgery & Associate Professor of Pediatric Surgery, Tepecik Training Hospital, Turkey, Kazim Dirik Mah, Mustafa Kemal Cad, Hakkibey apt. No:45 D.10 35100 Bornova-tzmir, Tel: +90 2324696969/90 542 4372747; Fax: +90 2324330756; Email: verikci@yahoo.com

Submission: July 21, 2017; Published: December 11, 2017

ISSN : 2576-9200Volume1 Issue3

Keywords

Keywords: Congenital neck mass; Thyroglossal duct remnant; Branchial cleft anomaly; Dermoid cyst

Introduction

Congenital neck lesions are common clinical concern in infants and children. The differential diagnosis includes congenital, inflammatory and neoplastic lesions. The physicians caring for children with congenital neck lesions (CNLs) should be aware of different presentations since these lesions are known to be complicated by infection. An orderly examination of the neck with a clear understanding of embryology and anatomy of the region will facilitate the diagnosis. Surgical intervention is cornerstone in the treatment and early referral of these patients for pediatric surgeons is recommended. The most common CNLs encountered in pediatric practice are thyroglossal duct remnants (TGDR) followed by branchial cleft anomalies (BCA) and dermoid cysts (DC) [1]. With a correct preoperative diagnosis and appropriate surgical management it is possible to prevent recurrence that is the most common complication in these lesions.

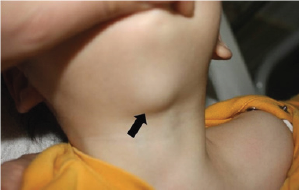

CNLs in children constitute one of the most intriguing areas of pediatric pathology and can produce diagnostic and therapeutic challenges for clinicians and surgeons. In the absence of infection, identification of a cystic mass in a child should raise the diagnosis of congenital malformations related to abnormal embryogenesis of the thyroglossal duct. TGDRs are the most common form of CNLs, accounting for up to 70-90% of such lesions [2-4]. In a recent report, more than half of the patients (53.4%) with CNLs presented with TGDR [5]. The true incidence is not known with certainty and in fact many are never detected clinically. A 7% incidence of TGDR in a postmortem study of 200 adults has been reported [6]. These lesions are commonly observed in children or adolescents and in a meta-analysis its incidence was found to be higher in children than in adults [7]. Although there are conflicting reports with regard to sex distribution [8-10], equal distribution among males and females has been reported in most of the reviews [7,11,12]. It should be kept in mind that a true female dominance does exist amongst familial TGDRs [13]. Main presentations of TGDR are that of a midline neck mass or infection as a single or a recurrent event (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Midline neck mass in a patient with TGDR (Arrow: midline neck mass).

Diagnostic methods in the preoperative evaluation of TGDR include US, CT, MRI, fine needle aspiration (FNA), radioisotope thyroid scanning, and thyroid function test [14]. US is the most common test ordered in children [15]. US is noninvasive and offers valuable information of both the TGDR and thyroid gland [16]. The absence of a normal appearing thyroid gland in the lower neck should alert the clinician that ectopic thyroid tissue might be present within the TGDR or elsewhere along the course of the thyroglossal duct and thyroid scintigraphy with thyroid function tests should be performed [17]. In the diagnostic work up, thoracic CT or MRI may be performed for the documentation of other comorbidities as such when the lesion is extensive crossing multiple anatomical spaces. Concerning FNA, although the diagnostic sensitivity of 62% and a positive predictive value of 69% is reported, it is not popular for diagnosing TGDR in children [14,18].

The most common location for the cystic mass in TGDR is close proximity to the hyoid bone with an incidence of 66%, but other locations including lingual, suprahyoid, suprasternal or within the thyroid gland have also been reported [7,19]. Although the incidence of complications including recurrence following the Sistrunk's procedure has been noted up to 29% [20], recurrence rate of TGDR after the procedure is reported to be 2.6% to 5% in most recent literature [21,22]. Deeper and wider excisions including removal of midportion of hyoid bone in patients without bone resection during the initial operation are suggested to remove any missed epithelial remnants during the subsequent operations in these patients with recurrence. Apart from recurrence, possible major complications of TGDR surgery such as abscess or hematoma requiring surgical drainage, inadvertent entry into the airway, tracheotomy, nerve paralysis, hypothyroidism are rare [23]. It is reported that fewer than 1% of patients with TGDRs may have malignant tissue, usually well differentiated thyroid carcinoma [24]. Minor complications may include seroma, local wound infection and dehiscence [20]. Although the Sistrunk's procedure is safe and successful technique with low complication rates, rare and life threatening complications should be kept in mind during the management of these children.

Figure 2: Bilateral second cleft fistula with mucoid discharge from the fistulae openings (Arrows: fistulae openings).

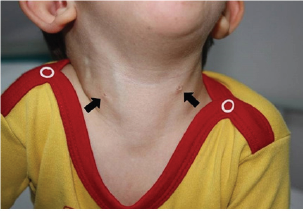

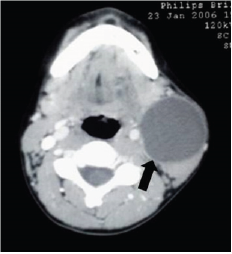

BCAs are the second most common CNL and comprise 20%-30% of all head and neck lesions [21,25-27]. It is reported that there is an equal sex distribution in BCAs [25,28]. Although branchial remnants are relatively rare, which can present in a variety of ways depending on the origin of the cleft, the most common type is the second cleft anomalies accounting for 95% of all lesions [1,5]. In classic cases, complete history and physical examination is adequate for diagnosis and no additional evaluation may be necessary (Figure 2). An upper airway endoscopy may be useful in determining the presence of a pharyngeal opening [21]. On the contrary to adults, FNA should not be performed and incisional biopsy should be avoided in children otherwise resection of branchial lesion will be technically more difficult [25]. US and CT may be helpful in defining the lesion and its anatomic course (Figure 3). These imaging modalities should be performed preoperatively for complete visualization of the tract [25]. Common current practice is to obtain a preoperative US for planning the treatment.

Figure 3: Axial CT image in a child with a second branchial cleft cyst (Arrow: cystic mass).

BCAs present as cysts, sinuses, or fistulae and clinical presentation heavily depends on the type of the lesion. Cysts present as swelling while sinuses or fistulae may produce clear discharge. In a recent study of the patients, 64% had discharging sinuses or fistulae and blind ending sinuses outnumbered other presentation types of BCA [5]. This finding is in accordance with the literature in that branchial fistulae and sinuses are diseases of childhood while cysts are more common in adults [29]. In the largest review of BCAs comprising 232 procedures, 90% of which included second branchial anomalies with an incidence of 13.5%, only 28 children with second branchial anomalies demonstrated complete fistulae [30].

Although studies of less invasive procedures are promising including sclerotherapy and endoscopic excision or cauterization, the definitive treatment of these lesions has historically been complete surgical excision of the entire tract [1,31]. There is controversy on the timing of the resection. Some suggest early resection in order to prevent infection whereas others advocate waiting until the ages of 2-3 years [25,32,33]. If there is prolonged period of symptoms before diagnosis and treatment, timing of surgical intervention may be during late period of childhood. Recurrence rates following surgical excision have been reported as high as 22% [34]. So during surgical treatment of these lesions meticulous technique should be performed. Sinus or fistula tracts of BCAs are typically lined by stratified squamous epithelia and some areas may also be replaced by respiratory epithelium [35,36].

Another lesion in the differential diagnosis of CNLs is DC which is a germ cell tumor that results from the inclusion of embryonic epithelial elements, and contains ectodermal and endodermal components [21,37]. Nomenclature of these lesions is quite confusing and not uniform. Although these lesions can be divided into epidermoid, dermoid and teratoid cysts based on the histological findings, the term DC has been used for all three lesions [38]. Cervical lesions typically present 20% of head and neck dermoids and are usually diagnosed before the age of 3 years [21]. After careful history and physical examination with an US, simple excision is all that is needed for cure. However if there is an attachment of the lesion with hyoid bone a Sistrunk's procedure should be performed [10].

Conclusion

In conclusion, the most common congenital neck masses include TGDR, BCA and DC. Surgical resection is optimal choice of therapy not only for aesthetic reasons but for the recurrent infections and the potential danger of malignancy especially for the cases with TGDR. Management of CNLs may be associated with high morbidity, especially recurrence. Since CNLs are known to be complicated by infection, early referral of these patients for pediatric surgeons and accurate and timely surgical treatment is suggested.

References

- LaRiviere CA, Waldhausen JHT (2012) Congenital cervical cysts, sinuses, and fistulae in Pediatric Surgery. Surg Clin North Am 92(3): 583-597.

- Shah R, Gow K, Sobol SE (2007) Outcome of thyroglossal duct cyst excision is independent of presenting age or symptomatology. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 71(11): 1731-1735.

- Thomas JR (1979) Thyroglossal-duct cysts. Ear Nose Throat J 58(12): 510-514.

- Pounds LA (1981) Neck masses of congenital origin. Pediatr Clin North Am 28(4): 841-844.

- Erikci V, Hojgör M (2014) Management of congenital neck lesions in children. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 67(9): e217-e222.

- Ellis PD, van Nostrand AW (1977) The applied anatomy of thyroglossal duct remnants. Laryngoscope 87(5 Pt 1): 765-770.

- Allard RH (1982) The thyroglossal cyst. Head Neck Surg 5(2): 134-146.

- Hsieh YY, Hsueh S, Lin JN (2003) Pathologic analysis of congenital cervical cysts in children: 20 years of experience at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital. Chang Gung Med J 26(2): 107-113.

- Al-Khateeb TH, Al Zaubi F (2007) Congenital neck masses: a descriptive retrospective study of 252 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 65(11): 22422247.

- Türkyilmaz Z, Sönmez K, Karabulut R (2004) Management of thyroglossal duct cysts in children. Pediatr Int 46(1): 77-80.

- Brousseau VJ, Solares CA, Xu M (2003) Thyroglossal duct cysts: presentation and management in children versus adults. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 67(12): 1285-1290.

- Lin ST, Tseng FY, Hsu CJ (2008) Thyroglossal duct cyst: a comparison between children and adults. Am J Otolaryngol 29(2): 83-87.

- Greinwald JH, Leichtman LG, Simko EJ (1996) Hereditary thyroglossal cysts. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 122(10): 1094-1096.

- Ren W, Zhi K, Zhao L (2011) Presentations and management of thyroglossal duct cyst in children versus adults: a review of 106 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 111(2): e1-e6.

- Brewis C, Mahadevan M, Bailey CM (2000) Investigation and treatment of thyroglossal cysts in children. J R Soc Med 93(1): 18-21.

- Ahuja AT, Wong KT, King AD (2005) Imaging for thyroglossal duct cyst:the bare essentials. Clin Radiol 60(2): 141-148.

- Koch BL (2005) Cystic malformations of the neck in children. Pediatr Radiol 35(5): 463-477.

- Shahin A, Burroughs FH, Kirby JP (2005) Thyroglossal duct cyst: a cytopathologic study of 26 cases. Diagn Cytopathol 33(6): 365-369.

- Foley DS, Fallat ME (2006) Thyroglossal duct and other congenital midline cervical anomalies. Semin Pediatr Surg 15(2): 70-75.

- Maddalozzo J, Venkatesan TK, Gupta P (2001) Complications associated with the Sistrunk procedure. Laryngoscope 111(1): 119-123.

- Enepekides DJ (2001) Management of congenital anomalies of the neck. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am 9(1): 131-145.

- Mohan PS, Chokshi RA, Moser RL (2005) Thyroglossal duct cysts: a consideration in adults. Am Surg 71(6): 508-511.

- Patel NN, Hartley BE, Howard DJ (2003) Management of thyroglossal tract disease after failed Sistrunk's procedure. J Laryngol Otol 117(9): 710-712.

- El Bakkouri W, Racy E, Vereecke A (2004) Squamous cell carcinoma in a thyroglossal duct cyst. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac 121(5): 303305.

- Waldhausen JH (2006) Branchial cleft and arch anomalies in children. Semin Pediatr Surg 15(2): 64-69.

- Albers GD (1963) Branchial anomalies. JAMA 183: 399-409.

- Torsiglieri AJ, Tom LW, Ross AJ 3 (1988) Pediatric neck masses: guidelines for evaluation. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 16(3): 199-210.

- Thomaidis V, Seretis K, Tamiolakis D (2006) Branchial cysts. A report of 4 cases. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Panonica Adriat 2006; 15(2): 85-89.

- Guldfred LA, Philipsen BB, Siim CJ (2012) Branchial cleft anomalies: accuracy of pre-operative diagnosis, clinical presentation and management. J Laryngol Otol 126(6): 598-604.

- Maddalozzo J, Rastatter JC, Dreyfuss HF (2012) The second branchial cleft fistula. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 76(7): 1042-1045.

- Goff JC, Allred C, Glade RS (2012) Current management of congenital branchial cleft cysts, sinuses, and fistulae. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 20(6): 533-539.

- Roback SA, Telander RL (1994) Thyroglossal duct cysts and branchial cleft anomalies. Semin Pediatr Surg 3(3): 142-146.

- O'Mara W, Amedee RG (1998) Anomalies of the branchial apparatus. J La State Med Soc 150(12): 570-573.

- Olusesi AD (2009) Combined approach branchial sinusectomy: a new technique for excision of second branchial cleft sinus. J Laryngol Otol 123(10): 1166-1168.

- Keogh IJ, Khoo SG, Waheed K (2007) Complete branchial cleft fistula: diagnosis and surgical management. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord) 128(1-2): 73-76.

- Benson MT, Dalen K, Mancuso AA (1992) Congenital anomalies of the branchial apparatus: embryology and pathologic anatomy. Radiographics 12(5): 943-960.

- Flint PW, Cummings CW (2010) Cummings otolaryngology head & neck surgery. (5 th edn), Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier.

- Batsakis JG (1979) Teratomas of the head and neck. In: Batsakis JG (Ed.), Tumors of the head and neck: clinical and pathological considerations, (2nd edn). Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)