- Submissions

Full Text

Research & Investigations in Sports Medicine

How to Write a “Prescription” for Physical Exercise

Neev Shah, Rifaat El Mallakh and Philip May*

Clinical Associate Professor of Medicine, University of Louisville School of Medicine, USA

*Corresponding author:Philip May, Clinical Associate Professor of Medicine, University of Louisville School of Medicine, USA

Submission: February 08, 2024;Published: February 22, 2024

ISSN: 2577-1914 Volume10 Issue2

Background

The 2018 American Physical Activity Guidelines recommend a minimum of 150 to 300 minutes per week of “moderate” exercise, 75 to 150 minutes per week of “vigorous/Intense” exercise or a combination of both [1] for all adult Americans, including those adults with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AIDD). AIDDs have been found to have increased minutes/week of sedentary behavior as well as reduced minutes/week of meaningful physical exercise [2,3]. This places AIDD at increased risk for many chronic physical and mental health conditions [4]. Therefore, it is important for all health professionals who treat AIDD to be able to determine their baseline “physical activity level” (i.e., minutes/week of both Sedentary behavior and Moderate/Vigorous physical activity) and prescribe effective patient-preferred endurance (aerobic) and/or resistance (strength-building) exercise programs [5-11]. While AIDDs will willingly wear activity watches [12], there has been difficulty “recording” their minutes of exercise due to lack of abilities of AIDDs and/or cooperation of their caregivers [13,14]. These measures are important because extensive research has shown that they are associated with increased risk for mental illness, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and many other diseases, as well as an overall increased mortality risk. The problem of documentation of exercise outcomes may be solved by using remote monitoring of fitness watch-generated exercise data, such as that provided by the Fitabase, Inc. company (Table 1). Fitabase, Inc., is a comprehensive data management platform primarily designed to support innovative research projects using wearable and internet-connected devices. Fitabase, Inc. collects all physical activity data tracked by Fitbit and Garmin devices. This includes steps, activity intensity, energy expenditure, and METs. Once a device is connected to Fitabase, the clinician or researcher can bring in that device’s data as soon as the wearable service makes it available. This usually happens immediately after the device synchronizes. (www.fitabase.com).

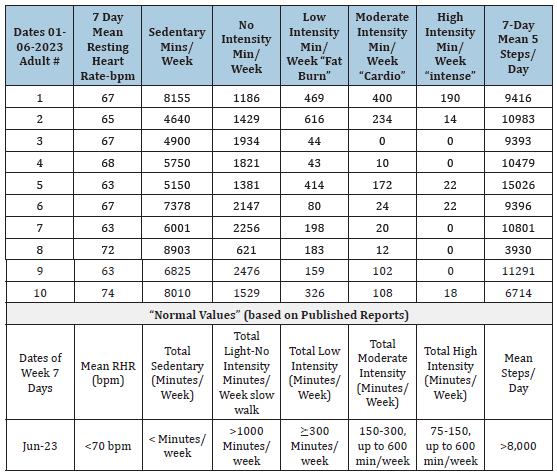

Table 1:Weekly Exercise results (out comes)–(7-different health parameters) from 10 “Neuro typical” (not IDD) adult men and women of various ages who have variable exercise programs [1].

Note: “Intensity” refers to degree (%) of age-corrected increase of heartrate.

Results: Only 3 participants (30%) met the US standard for moderate exercise (150-300 min/week). Only 1 participant

met the US government Standard for high intensity exercise. Most of these individuals were health professionals.

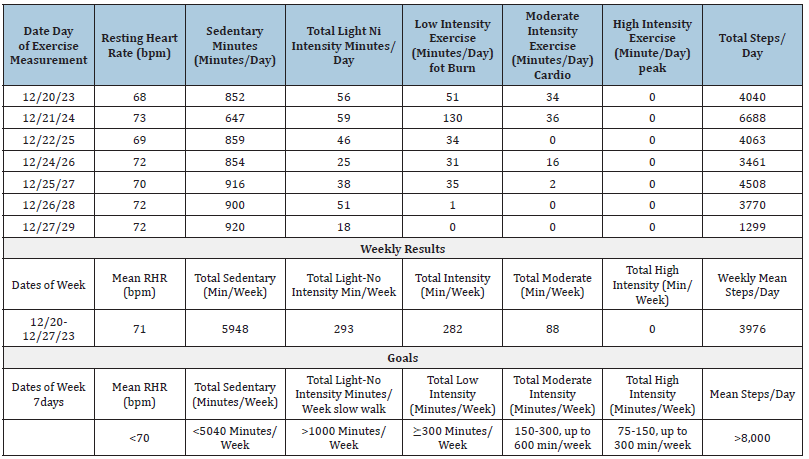

To measure exercise in our patients, we currently use The Fitabase, Inc. system (www.fitabase.com) which allows the user of a Fitbit or Garmin activity watch to automatically record seven parameters of fitness, namely, 1)Resting heart rate [15], 2) Sedentary minutes per day [16], 3)“Light” exercise minutes per day [16], “Active” (heartrate-increasing) minutes per day of 4)Mild, 5) Moderate or 6)Intense heartrate increasing exercise [17] and 7) Steps-per day. It has recently been shown that higher levels of total physical activity, at any intensity, and less time spent sedentary, are associated with substantially reduced risk for premature mortality, with evidence of a non-linear dose-response pattern in middle aged and older adults [5]. In addition, it has been shown that being sedentary for more than 12 hours per day was associated with 38% higher mortality risk, but only among individuals accumulating less than 22min per day of Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity [18]. Thus, if individuals obtain at least 22 minutes per day (or 154 minutes/week) of moderate physical activity the risk from sedentary behavior is eliminated. These data can be used by the primary care health professional to inform and advise his/her patient/client regarding whether adequate levels of these seven parameters of exercise have been obtained (www.fitabase.com) and to provide recommendations for an individualized patient/ client preferred exercise program/routine, and feedback regarding progress in obtaining measurable goals. Table 2 demonstrates the results from an overweight 30-year-old man with Limb Girdle Muscular Dystrophy. He began an exercise program in a community pool and was able to attain a significant number of minutes of meaningful exercise, which he tolerated well. It will be easier for him to eliminate the risk from his increased sedentary minutes by increasing his exercise (if tolerated), than directly attempting to reduce the number of sedentary minutes. This is an example of how the primary care health provider, by using Fitbit watch/Fitabase collected exercise data can create an exercise “prescription” for his/ her patient.

Table 2:Patient physical activity report form.

Name: Deidentified adult with limb girdle muscular dystrophy; Date of Birth: Deidentified; Age: Deidentified; Gender:

Deidentified.

Impression: (Note: No exercise recorded on 12/23/23): First week of monitoring exercise in pool. “intensity” refers

to increase of heart rate, with percent of “maximum heart rate” 220=29=191 beats per minute for Zachary. He did

demonstrate significant (“heart pumping”) exercise. Optimal goal would be 150 minutes of “moderate” per government

guidelines, but it is unknown whether he can tolerate this much exercise. He has almost normal “low intensity” levels.

He might focus on attaining > 300 min/week of low intensity exercise as initial goal or reduction of sedentary minutes.

Achieving the American Activity Guidelines for Exercise reduces the risk for 35 different health conditions, including Heart Attacks, strokes, cancer, osteoporosis, obesity, anxiety/ depression, periodontal disease, aging-related hearing loss and Alzheimer’s Disease [4]. Obtaining these objectives will require motivation of the health professional to support his/her AIDD patient in a meaningful exercise program. Unfortunately, there is evidence that currently, physician support for this type of service is lacking in the general population [19] and especially so for AIDD [8]. For the reasons discussed above, we believe that if health professionals were familiar with and comfortable in utilization of the “remote” Fitabase system and were then able to discuss objective exercise outcomes with their patients, their AIDD patients and their caregivers [20] would be more likely to cooperate with an individualized, evidence-based health promoting physical exercise program. Finally, a recent article in JAMA [18] indicated that clinicians should now be encouraged to recommend physical activity for their patients using the various health parameters determined by activity devices as guides to establish goals and objectives for physical exercise. It was also recommended in this same article that the “clinicians themselves should hew to the same advice not only to set an example but also to personally experience and understand potential barriers that can exist”.

References

- Piercy K (2018) The physical activity guidelines for Americans. JAMA 320(19): 2020-2028.

- Elinder L (2010) Promoting a healthy diet and physical activity in adults with intellectual disabilities living in community residences: Design and evaluation of a cluster-randomized intervention. BMC Public Health 10: 761.

- Simon Siles S (2022) Effects of exercise on fitness in adults with intellectual disability: A protocol of an overview of systematic reviews. Disabil Rehabil 41(26): 3118-3140.

- Booth F (2012) Lack of exercise is a major cause of chronic diseases. Compr Physiol 2(2): 1143-1211.

- Hassan N (2019) Effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity in individuals with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 63(2): 168-191.

- Oviedo G (2014) Effects of aerobic, resistance and balance training in adults with intellectual disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities 35(11): 2624-2634.

- Weterings S (2020) The feasibility of vigorous resistance exercise training in adults with intellectual disabilities with cardiovascular disease risk. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil 33(3): 488-495.

- Martin Peter (2019) Medical treatment for people with intellectual impairment: A particular challenge for the health service. Dtsch Arztebl Int 116(48): 807-808.

- Pestana M (2018) Effects of physical exercise for adults with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review. J Phys Educ 41(26): 3118-3140.

- Fjellstrom S (2022) Web-based training intervention to increase physical activity level and improve health for adults with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 66(12): 967-977.

- Shields N (2013) A community-based strength training program increases muscle strength and physical activity in young people with Down syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. Research in Developmental Disabilities 34(12): 4385-4394.

- Brewer W (2017) Validity of fitbit’s active minutes as compared with a research-grade accelerometer and self-reported measures. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 3(1): e000254.

- Bains K, Turnbull T (2020) Using a theoretically driven approach with adults with mild moderate intellectual disabilities and carers to understand and improve uptake of healthy eating and physical activity. Obesity Medicine 19: 100234.

- Tudor Locke C (2011) How many steps/days are enough? For older adults and special populations. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 8: 80.

- Reimers (2018) Effects of exercise on the resting heart rate: A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventional studies. J Clin Med 7(12): 503.

- Dohrn I (2018) Replacing sedentary time with physical activity: A 15-year follow-up of mortality in a national cohort. Clinical Epidemiology 10: 179-186.

- Grassler B (2021) Effects of different exercise interventions on heart rate variability and cardiovascular health factors in older adults: A systematic Review. European Review of Aging and Physical Activity 18(1): 24.

- Lee I Min, Keadle S, Matthews C (2023) Fitness trackers to guide advice on activity prescription. JAMA 330(18): 1733-1734.

- Asif I (2022) Exercise medicine and physical activity promotion: Core curricula for US medical schools, residencies and sports medicine fellowships: developed by the American medical society for sports medicine and endorsed by the Canadian academy of sport and exercise medicine. Br J Sports Med 56(7): 369-375.

- Angba Tessy (2020) Exercise counseling for intellectual disabled care givers in Ibadan: How beneficial? Sapiential Foundation Journal of Education, Sciences and Gender Studies (SFJESGS) 2(3): 25-37.

© 2024 Philip May. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)