- Submissions

Full Text

Research & Investigations in Sports Medicine

Safety of Applying Cupping Therapy to Treat Musculoskeletal Pathologies

Cage SA1*, Peebles RL3,5, Coulombe B4, Warner BJ2, Gallegos DM1,3, Galbraith RM3,5 and Cox C1

1University of Texas at Tyler, USA

2Grand Canyon University, USA

3UT Health East Texas, USA

4Texas Lutheran University, USA

5University of Texas Health Science Center, USA

*Corresponding author: Cage SA, University of Texas at Tyler, USA

Submission: November 18, 2021;Published: December 03, 2021

ISSN: 2577-1914 Volume8 Issue1

Abstract

Cupping therapy is becoming a popular therapeutic modality employed by athletic trainers and other allied healthcare professionals. It uses negative pressure to reduce pain, increase blood flow, and improve muscle function. Like many other therapeutic interventions, adverse effects related to cupping therapy treatment can occur. The majority of these effects-particularly muscle soreness-are mild and similar to those encountered in other treatments. While severe adverse events following treatment with cupping therapy have been reported, these events are rare and can often be explained by poor clinician education or flawed methodology. The risks associated with cupping therapy are comparable to, and sometimes fewer than, those associated with other contemporary therapeutic interventions. Proper clinician education, methodology, patient education, and patient communication are crucial when attempting to mitigate the risk of adverse effects related to cupping therapy.

Introduction

Cupping therapy, or myofascial decompression, is a therapeutic technique that has been documented as early as 3300 BC [1]. Used by healthcare professionals globally, cupping creates negative pressure at the treatment site for the purpose of increasing blood flow, reducing pain, increasing flexibility, and increasing function [2-4]. After receiving mainstream exposure during the 2016 Olympics, cupping therapy began to grow in popularity in the United States and Western Europe [1]. Some of this popularity can be attributed to increased media interest resulting from popular athletes, such as Michael Phelps, having received this type of treatment [5,6]. While there remains no consensus on a standardized methodology for prescribing and applying cupping therapy to either amateur or professional athletes, this treatment technique continues to grow in popularity [1]. The lack of consensus can be attributed in part to a lack of high-quality studies and no agreed-upon standardized methodology [4,7]. A clinical experts’ statement was published in 2019 to provide some level of guidance to clinicians looking to use cupping therapy. However, the need for well-designed, rigorous studies is still apparent [8].

Previous studies have reported that cupping therapy has a positive effect on both local and regional blood flow [3,9,10]. When a cup is applied to the treatment site, the underlying tissue is subjected to negative pressure that results in compression of the tissue in contact with the rim of the cup and decompression of the tissue inside the cup. The lower pressure within the cup can lead to a pressure differential between the skin within the cup and the underlying superficial blood vessels [11]. When exposed to this change in pressure, vasodilation occurs, which causes localized increased blood flow at the treatment site [11]. This increased blood flow may be the mechanism resulting in reduced pain outcomes found in research [12].

There may also be other mechanisms through which cupping therapy can modulate pain. It has been reported that while the marks left on the body by cupping therapy are healing, macrophages are attracted to the treatment site [12]. The prevalence of the enzyme heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) has been found to increase in tissues treated with cupping therapy [12]. As the body catalyzes HO-1, the bi-products include heme, biliverdin, bilirubin, carbon monoxide, and iron [12]. During this process, iron is sequestered by ferritin, and the other biproducts have antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and neuromodulary effects that may create a more optimal environment for healing and ultimately pain reduction [12].

As previously mentioned, cupping therapy has increased in popularity among clinicians in recent years. Researchers have also begun a more extensive investigation into the uses of cupping therapy when caring for athletes [1]. Additionally, recent studies have reported that cupping therapy is used by the majority of clinical athletic trainers surveyed [13-15]. However, some clinicians and patients have expressed reservations regarding cupping therapy’s safety. Thus, the purpose of this review is to describe the safety of cupping therapy as a therapeutic modality for musculoskeletal pain.

Safety of Cupping Therapy

Within the current literature, there do not appear to be any systematic reviews or clinical trials that have reported severe adverse effects from cupping therapy [16-19]. One study went so far as to state that cupping therapy has fewer side effects than acetaminophen when treating musculoskeletal pain [18]. The authors noted particular concern regarding the effects that oral analgesics might have on the upper gastrointestinal tract [18]. Indeed, most of the reported mild adverse effects of cupping therapy are similar to those of other commonly used therapeutic modalities [16]. However, cases of adverse events following cupping therapy have been reported, particularly when performed improperly or by an untrained professional.

Muscle Soreness

The most commonly reported side effect of cupping therapy is muscle soreness at the treatment site [16,19]. This discomfort can be due to several factors, including the amount of negative pressure applied and the frequency and duration of the treatments. Despite this potential effect, the level of discomfort was notably reported to be tolerable in one study [19]. When compared to other therapeutic interventions, mild muscular soreness is not an uncommon side effect [20,21]. One case report of a patient who had been treated with massage resulted in severe radicular pain [22]. While muscular pain is certainly something clinicians must attempt to minimize when performing any treatment, proper cupping therapy training and techniques appear to minimize these concerns [8,16,23].

Skin Conditions

The circular marks that may appear during or after cupping therapy can elicit negative emotions from patients [24]. Researchers have noted that these responses can lead to patients being reluctant to continue receiving cupping therapy [24]. Therefore, it is important that clinicians educate patients on the nature of these marks, as such knowledge may help to resolve patients’ concerns.

When cupping therapy is applied, the negative pressure that is created can cause the underlying capillaries to dilate. This dilation can lead to capillary rupture and subsequent ecchymosis [12]. When capillary rupture occurs, macrophages become attracted to the treatment site, and this stimulates the production of HO-1 [12]. Based on this information, the marks left by cupping therapy may be a factor in creating a more optimal healing environment. As part of patient education, it is important to note that while cupping marks are similar in appearance to bruises, they do not have the accompanying trauma to non-vascular tissue that is associated with traumatic injuries [12].

Another effect that cupping therapy has been reported to have on treatment sites is blistering of the skin [24-27]. The majority of the literature reporting blistering following cupping therapy is in the form of case studies [24-26]. In these cases, the common factor was flawed methodology. One case involved a clinician who had not been trained in the prescription and application of cupping therapy [25]. Another reported a patient receiving cupping therapy while his private airplane was airborne, and the cabin was pressurized [27]. All these cases reasserted the need for proper training and education prior to using cupping therapy [24-26]. Studies that investigated the contents of blistered skin found no harmful pathogens [26,27]. One study found that the blister fluid contained proteins that have been shown to play a role in anti-oxidation, tissue repair, and metabolic reactions [27]. While blistering should be avoided through proper clinician training and education, if a blister does occur, normal wound care procedures should be followed [8].

Severe Events

As with many treatment techniques, severe adverse effects related to cupping therapy have been reported. Similar to the aforementioned side effects, within skin and muscle, the evidence on these severe events is limited to case reports. While these cases are noteworthy and should serve as cautionary information for clinicians, such adverse effects would likely be reported in more literature if they were widely prevalent. Some of these severe events included iron deficiency anemia, intraperitoneal hemorrhage, and cervical artery dissection [25,28,29]. Once again, these cases were the result of improperly trained clinicians using flawed methodology.

Precautions

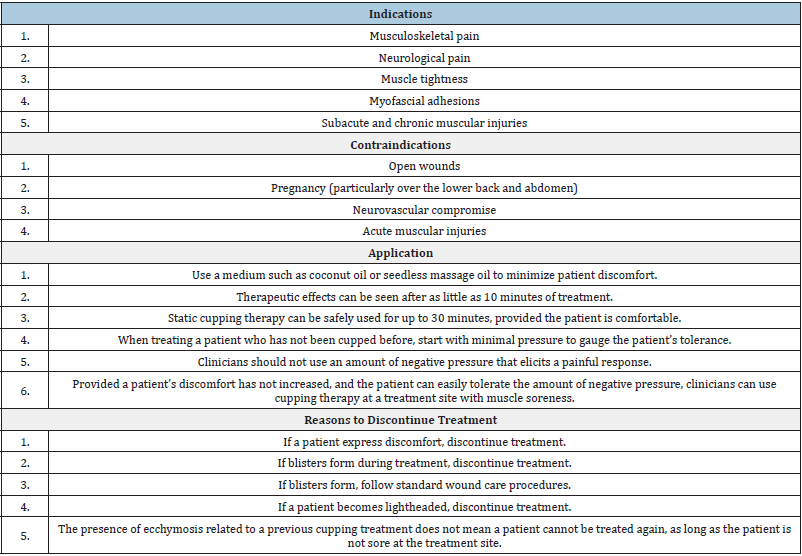

As with many other modalities, cupping therapy can result in adverse effects for patients. The risk of these events occurring increases when clinicians are improperly trained or use unsafe treatment methods [8,23]. Currently, there is a paucity of high level, rigorous, randomized controlled trials that would be required to create an evidence-based standardized method of practice [1,8]. In this absence of evidence, researchers have published an expert-driven statement on recommendations for cupping therapy prescription and application [8]. These recommendations are presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Recommendation for the prescription and application of cupping therapy [8].

Summary

The purpose of this review was to describe the currently available literature related to the safety of using cupping therapy to treat muscular pain. While the current literature does report that cupping therapy has potential adverse effects, these events are mostly mild in nature [16]. The risk of both mild and severe adverse effects can be mitigated through proper techniques and training [16,23]. Provided clinicians undergo education and training, cupping therapy appears to be a safe treatment for muscular pain. Clinicians should also be sure to educate their patients on the nature of these effects prior to treatment, particularly the circular marks that can occur during or after cupping therapy [12].

In comparison with other therapeutic interventions, cupping therapy appears to have comparable or fewer potential adverse effects. Massage, therapeutic ultrasound, electrical stimulation, ibuprofen, acetaminophen, and cold-related modalities have all been reported as having potentially adverse effects [20-22,30- 35]. Regarding systemic effects, cupping therapy has fewer risks than ibuprofen or acetaminophen [30,31,35]. When reviewing the literature on effects on the skin, more cases of adverse effects appear to have been reported for electrical stimulation without the same potential therapeutic benefits of marks left by cupping therapy [33,34]. Based on this information, cupping therapy appears to be a reasonably safe therapeutic modality compared to other contemporary interventions.

In conclusion, cupping therapy is a therapeutic modality that is widely used by allied healthcare professionals. As this treatment continues to grow in popularity, clinicians need to be aware of its potential adverse effects. Provided clinicians have undergone proper training and employ the proper technique, cupping therapy is a relatively safe treatment option for muscular pain. Patient education and communication before, during, and after treatment are critical to ensuring that patients are at minimal risk for an adverse outcome.

References

- Bridgett R, Mas D, Prac C, Klose P, Duffield R, et al. (2018) Effects of cupping therapy in amateur and professional athletes: Systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Altern Complement Med 24(3): 208-219.

- Cage SA, Warner BJ, Gallegos DM, Sims-Koenig K (2020) Effects of cupping therapy on Lower Quarter Y-Balance Test scores in collegiate baseball players. Res Inves Sports Med 6(1): 466-468.

- Arce-Esquivel A, Warner B, Gallegos D, Cage SA (2017) Effect of dry cupping therapy on vascular function among young individuals. International Journal of Health Sciences 5(3): 10-15.

- Cao H, Li X, Yan X, Wang N, Bensoussan A, et al. (2014) Cupping therapy for acute and chronic pain management: A systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medical Sciences 1(1): 49-61.

- Futterman M (2016) Michael Phelps leads Rio cupping craze. The Wall Street Journal.

- Lyons K (2016) Interest in cupping therapy spikes after Michael Phelps gold win. The Guardian.

- Cao H, Li X, Liu J (2012) An updated review of the efficacy of cupping therapy. PLoS ONE 7(2).

- Cage SA, Gallegos DM, Coulombe, Warner BJ (2019) Clinical experts statement: The definition, prescription, and application of cupping therapy. Clinical Practice in Athletic Training 2(2): 4-11.

- Cage SA, Warner BJ, Gallegos DM (2020) Effect of cupping therapy on skin surface temperature in healthy individuals. Journal of Sports Medicine and Allied Health Sciences 5(3).

- Chi L, Lin L, Chen C, Wang S, Lai H, et al. (2016) The effectiveness of cupping therapy on relieving chronic neck and shoulder pain: A randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med.

- Liu W, Piao S, Meng X, Wei L (2013) Effects of cupping on blood flow under the skin of back in healthy human. World Journal of Acupuncture-Moxibustion 23(3): 50-52.

- Lowe D (2017) Cupping therapy: An analysis of the effects of suction on the skin and possible influence on human health. Complement Ther Clin Pract 29: 162-168.

- Cage SA, Warner BJ, Gallegos DM, Winkelmann ZK (2020) Athletic trainers’ perceived and actual knowledge of cupping therapy concepts. Journal of Sports Medicine and Allied Health Sciences 5(3).

- Cage SA, Winkelmann ZK, Warner BJ, Gallegos DM (2020) Perceived and actual knowledge of cupping therapy concepts among athletic training preceptors in CAATE accredited programs. Research & Investigations in Sports Medicine 6(3): 514-518.

- Cage SA, Warner BJ, Gallegos DM, Goza JP, Winkelmann ZK (2020) Perceived and actual knowledge of cupping therapy concepts among athletic trainers in the state of Texas. Research & Investigations in Sports Medicine 6(4): 538-542.

- Cao HJ, Han M, Zhu X, Liu J (2015) An overview of systematic reviews of clinical evidence for cupping therapy. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 2: 3-10.

- Cao HJ, Zhang YJ, Zhou L, Xie ZG, Zheng RW, et al. (2020) Partially randomized patient preference trial: Comparative evaluation of fibromyalgia between acupuncture and cupping therapy (PRPP-FACT). Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice 41.

- Khan AA, Jahangir U, Urooj S (2013) Management of knee osteoarthritis with cupping therapy. J Adv Pharm Technol Res 4(4): 217-223.

- Murray D, Clarkson C (2019) Effects of moving cupping therapy on hip and knee range of movement and knee flexion power: A preliminary investigation. Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy 27(5): 287-294.

- Ricci V, Ozcakar L (2020) Ultrasound imaging of the paraspinal muscles for interscapular pain after back massage. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation 29(6): 830-832.

- Miller DL, Smith NB, Bailey MR, Czamota GJ, Hynynen K, et al. (2012) Overview of therapeutic ultrasound application and safety considerations. J Ultrasound Med 31: 623-634.

- Zhang X, Wang JJ, Guo Y, Dong S, Shi W, et al. (2020) Sudden aggravated radicular pain caused by hemorrhagic spinal angiolipomas after back massage. World Neurosurgery 134: 383-387.

- Chen B, Guo Y, Li MY, Chen ZL, Guo Y (2016) Standardization of cupping therapy may reduce adverse effects. QJM: QJM 287.

- Azizpour A, Nasimi M, Shakeoi S, Mohammadi F, Azizpour A (2018) Bullous pemphigoid induced by Hijama therapy (cupping). Dermatol Pract Concept 8(3): 163-165.

- Kim KH, Kim TH, Hwangbo M, Yang GI (2012) Anaemia and skin pigmentation after excessive cupping therapy by an unqualified therapist in Korea. Acupunct Med 30(3): 227-228.

- Lin CW, Wang JT, Choy CS, Tung HH (2009) Iatrogenic bullae following cupping therapy. J Altern Complement Med 15(11): 1243-1245.

- Liu Z, Chen C, Li X, Zhao C, Li Z, et al. (2018) Is cupping therapy harmful? A proteomics analysis of blister fluid induced by cupping therapy and scald. Complement Ther Med 36: 25-29.

- Lu MC, Yang CJ, Tsai SH, Hung CC, et al. (2020) Intraperitoneal hemorrhage after cupping therapy. Hong Kong Journal of Emergency Medicine 27(2): 107-109.

- Zuhorn F, Schabitz WR, Oelschlager C, Klingebiel R, Rogalewski A (2020) Cervical artery dissection caused by electrical cupping therapy with high negative pressure: Case report. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases 29(11).

- Chun LJ, Tong MJ, Busuttil RW, Hiatt JR (2009) Acetaminophen hepatotoxicity and acute liver failure. J Clin Gastroenterol 43(4): 342-349.

- Fontana RJ (2008) Acute liver failure including acetaminophen overdose. Med Clin North Am 92(4): 761-794.

- Stagnell S, Burrows G (2016) Accidental ice-burn. British Dental Journal 221(4): 149.

- Fagan J, Klepeiss S (2019) Epidermal and dermal burns overlying surgical hardware after electrical stimulation. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 79(3).

- Fary RE, Briffa NK (2011) Monophasic electrical stimulation produces high rates of adverse skin reactions in healthy subjects. Physiother Theory Pract 27(3): 246-251.

- Balestracci A, Ezquer M, Elmo ME, Molini A, Thorel C, et al. (2015) Ibuprofen-associated acute kidney injury in dehydrated children with acute gastroenteritis. Pediatr Nephrol 30(10): 1873-1878.

© 2021 Cage SA. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)