- Submissions

Full Text

Research & Investigations in Sports Medicine

LGB-KASH and Shortened Workplace Incivility Scale Scores Among Athletic Trainers: A Pilot Study

JP Goza1,2, SA Cage3,4*, M Decker5, BJ Warner2,4 and DM Gallegos3

1Collin College, USA

2Grand Canyon University, USA

3University of Texas at Tyler, USA

4University of North Carolina, USA

5University of Texas at Arlington, USA

*Corresponding author: SA Cage, University of Texas at Tyler, University of North Carolina, Greensboro, USA

Submission: July 19, 2021;Published: July 27, 2021

ISSN: 2577-1914 Volume7 Issue5

Abstract

Current literature suggests that Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, and Asexual (LGBTQIA) athletic trainers encounter difficulties in their workplace given their status as minorities. Previous studies have examined the attitudes of athletic trainers towards LGBTQIA patients but have not looked into attitudes of athletic trainers and coaches towards LGBTQIA athletic trainers. However, in order to effectively assess these attitudes, it is important to have a valid and reliable instrument to do so. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to describe the scores on the LGB-KASH and Shortened Workplace Incivility Scale among credentialed athletic trainers in the state of Texas. A total of 42 credentialed athletic trainers participated in this study (age= 33 ± 10 years, certified experience = 11 ± 10 years). Participants were sent an electronic survey by email that gathered data on demographics, LGB-KASH scores, and Shortened Workplace Incivility Scale scores. Measures of central tendency (means, standard deviations, frequencies) were calculated for all survey items. Pearson Correlations were used to assess correlations between age, years of experiences, all subcategories of the LGB-KASH, and the Shortened Workplace Incivility Scale. An independent samples t-test was performed to determine differences between responses from heterosexual participants and gay, lesbian, and bisexual participants. Data analysis yielded several significant correlations. There was a low positive correlation between age and the Hate subcategory, and a low negative correlation between age and the Civil Rights subcategory. There was also a high negative correlation between the Hate subcategory and the Civil Rights subcategory. There were also significant differences between groups in the Knowledge, Religious Conflicts, and Internalized Affirmation subcategories. There were no significant differences in the Hate or Civil Rights subcategories, or on the Shortened Workplace Incivility Scale. Future research should examine the causes of the correlations described in this pilot study. Future research should also be directed towards examining the impact of lack of education and knowledge of LGBTQIA individuals and the issues they encounter on feelings of discomfort and self-consciousness.

Introduction

It has been documented in the literature that Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, and Asexual (LGBTQIA) athletic trainers encounter difficulties in their workplace given their status as minorities [1,2]. To date, there has been little research conducted to investigate the challenges and concerns of LGBTQIA allied healthcare professionals, in particular athletic trainers. Previous research has been conducted that suggests that patients generally have a positive opinion of athletic trainers who identified as LGBTQ [1]. Studies have also explored the perceptions of athletic trainers regarding LGBTQIA patients [3-5]. However, there does not appear to be any published research that would reflect the opinions of athletic trainers on fellow athletic trainers who are LGBTQIA.

One validated measure of the knowledge and attitudes of

individuals toward LGBTQIA persons is the Lesbian, Gay, and

Bisexual Knowledge and Attitudes Scale for Homosexuals (LGBKASH)

[6,7]. First developed in 2005 through the collective

findings of four studies, the LGB-KASH utilizes a series of questions

to provide a measure of the knowledge and attitudes held by

individuals regarding lesbians, gays, and bisexuals [7]. Further

research was conducted in 2019 to further validate the use of this

instrument as a reliable measure [6].

Another instrument that has the potential to help describe and

assess the experiences and environments LGBTQIA athletic trainers

work in is the Workplace Incivility Scale. This scale has been used

across multiple industries and across the globe to determine

whether or not an individual was working in a setting that would

allow them to flourish [8-11]. In 2018, a shortened version of this

scale was created and validated in order to create a more concise

measure of incivility in the workplace [8].

While both the LGB-KASH and Workplace Incivility Scale have

been validated across multiple populations, there does not appear to

be any previous studies utilizing these instruments with an athletic

training population. Prior to a larger scale study being conducted

on athletic trainers’ knowledge and attitude towards LGBTQIA

athletic trainers, it would be worthwhile to conduct a pilot study

of a smaller sampling of the target population. Thus, the purpose

of this pilot study was to describe the scores on the LGB-KASH and

Shortened Workplace Incivility Scale among credentialed athletic

trainers in the state of Texas. A secondary purpose was to examine

the difference in scores between heterosexual athletic trainers and

gay, lesbian, and bisexual athletic trainers.

Methods

Design

This study was conducted using a cross-sectional design using an electronic survey for data collection.

Participants

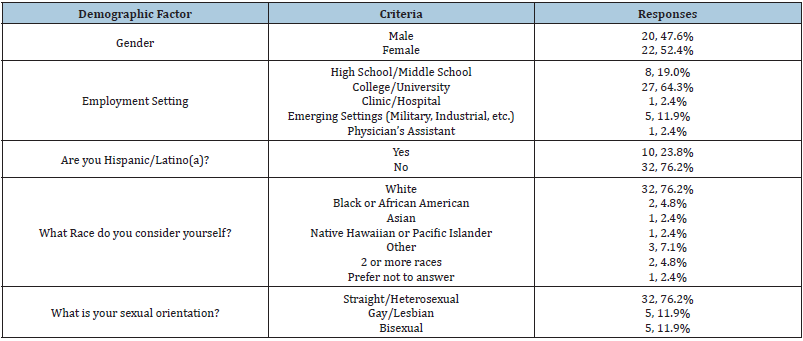

Participants were recruited for this study by emailing the athletic training staffs at NCAA Division I, II, and III institutions, and emailing the membership database for the East Texas Athletic Trainers’ Association. A total of 42 athletic trainers opened and completed the survey (age= 33 ± 10 years, certified experience = 11 ± 10 years). Demographic information for the participants is presented in Table 1. All participants were informed of the survey’s purpose and aims at the start of the survey. Informed consent was then obtained based on the protocol approved by the University of Texas at Tyler Institutional Review Board.

Table 1: Totals and percentage for participant demographic information.

Data collection

An email was sent to the athletic trainers in the East Texas Athletic Trainers’ Association membership database, and to athletic trainers in the state of Texas whose contact information was publicly available on their organization’s website. The email invited all prospective participants to participate in an electronic survey via a link from a web-based server (Qualtrics Inc., Provo, UT) in July 2021. The invitation contained information about the authors, the purpose and aims of the study, and assurances that the participants could quit the survey at any time. A follow-up email was sent to program directors a week after the initial email, and the survey was left open for a week prior to the survey being closed for statistical analysis to begin.

Instrument

Following the informed consent and demographics section, the instrument contained questions taken from the LGB-KASH to gather information regarding the participants’ knowledge and attitudes toward LGBTQIA persons. Participants were asked to answer 28 questions on a scale of 1 “Very uncharacteristic of me or my views” to 6 “Very characteristic of me or my views”. Participants were then asked to answer the four questions taken from the Shortened Workplace Incivility Scale on a scale of 1 “Never” to 5 “Many Times”. The responses were broken down into subcategories described in Table 2.

Table 2: LGB-KASH subcategories and descriptions.

Ultimately, the survey consisted of 41 questions. These questions included: one question regarding informed consent, five multiple-choice and two fill in the blank questions on demographics, 28 multiple choice questions from the LGB-KASH, and four multiple choice questions from the Shortened Workplace Incivility Scale.

Statistical analysis

Data were downloaded and analyzed using commercially available statistics software (SPSS Version 27, IBM, Armonk, NY). A total of 42 completed responses were included in the data analysis. Measures of central tendency (means, standard deviations, frequencies) were calculated where appropriate. Pearson Correlations were used to assess correlations between age, years of experiences, all subcategories of the LGB-KASH, and the Shortened Workplace Incivility Scale. An independent samples t-test was performed to assess differences between responses from heterosexual participants and gay, lesbian, and bisexual participants.

Results

LGB-KASH scores

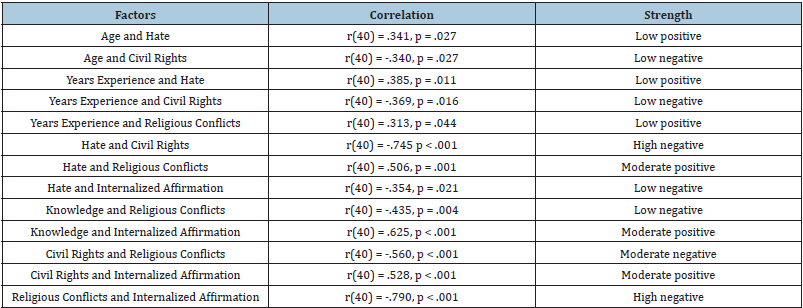

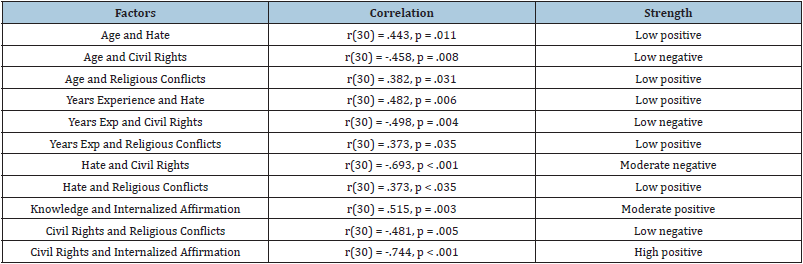

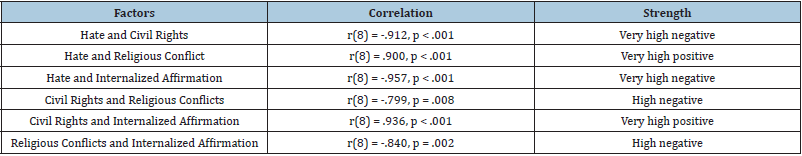

Average scores and standard deviations for scores on LGBKASH subcategories are included in Table 3. When looking at the responses of all participants, several correlations were statistically significant. Significant correlations from the entirety of the participant population are included in Table 4. Significant correlations for heterosexual participants are included in Table 5. Significant correlations for gay, lesbian, and bisexual participants are included in Table 6.

Table 3: LGB-KASH scores.

Table 4: Significant correlations in all participants

Table 5: Significant correlations in heterosexual participants

Table 6: Significant correlations in lesbian, gay, and bisexual participants.

When assessing differences in scores on the LGB-KASH between heterosexual participants and gay, lesbian, and bisexual participants, there was a significant difference in the Knowledge subcategory (Heterosexual = 2.19 ± 0.92, LGB = 3.64 ± 1.28), t(40) = -3.95, p < .001. A significant difference was also found in the Religious Conflicts subcategory (Heterosexual = 3.02 ± 1.08, LGB = 2.03 ± 1.18, t(40) = 1.12, p = .016). There was also a significant difference in the Internalized Affirmation subcategory (Heterosexual = 3.32 ± 1.46, LGB = 5.28 ± 1.34), t(40) = -3.78, p = .001. There were no other subcategories that had a significant difference between groups.

Shortened workplace incivility scale

On the Shortened Workplace Incivility Scale, there were no correlations found between age and years’ experience and scores on the scale. Furthermore, there were no significant differences found between heterosexual participants (1.89 ± 0.97), and gay, lesbian, and bisexual participants (2.03 ± 1.03).

Discussion

The purpose of this pilot study was to describe the scores on

the LGB-KASH and Shortened Workplace Incivility Scale among

credentialed athletic trainers in the state of Texas. A secondary

purpose was to examine the difference in scores between

heterosexual athletic trainers and gay, lesbian, and bisexual athletic

trainers.

Our findings indicated several significant correlations between

age, years of experience, and different subcategories of the LGBKASH.

There was a low positive correlation between age and the

Hate subcategory, and a low negative correlation between age

and the Civil Rights subcategory. This indicated that older athletic

trainers might be more likely to be self-conscious around LGB

individuals and less likely to overtly support the civil rights of LGB

individuals. There was also a high negative correlation between

the Hate subcategory and the Civil Rights subcategory. This

indicated that individuals who were less self-conscious around

LGB individuals were more likely to support the civil rights of LGB

individuals overtly. A moderate positive correlation between the

Knowledge and Internalized Affirmation subcategories indicated

that individuals with more knowledge about LGB individuals and

the issues they face were more likely to engage in social activism

activities designed to advocate for LGB individuals. Lastly, there

was a high negative correlation between the Religious Conflicts

and Internalized Affirmation subcategories. This indicated that

individuals who were conflicted about their feelings and beliefs

toward LGB individuals based on their religion or faith were less

likely to engage in social activism activities designed to advocate

for LGB individuals.

When participants were separated by sexual orientation, the

high negative correlation between the Civil Rights and Internalized

Affirmation subcategories remained among heterosexual athletic

trainers. However, this same correlation did not exist among gay,

lesbian, and bisexual athletic trainers. When compared between

groups, the only subcategories with significant differences were

Knowledge, Religious Conflicts, and Internalized Affirmation. This

suggested that gay, lesbian, and bisexual athletic trainers were more likely to be knowledgeable and comfortable with LGBTQIA

issues. Furthermore, the results suggested that heterosexual

athletic trainers were more likely to experience conflictions with

their feelings and beliefs toward LGB individuals based on their

religious beliefs.

Previous research has indicated that athletic trainers have a

generally positive view of LGBTQIA patients and providing care

for them [3-5]. These studies also suggested that while athletic

trainers may be willing to provide care for LGBTQIA patients, they

may need to improve their knowledge of healthcare issues specific

to LGBTQIA patients [3-5]. The findings of this study regarding

LGBTQIA knowledge differences between heterosexual and gay,

lesbian, and bisexual athletic trainers appears to support these

previous studies.

When examining the environments at the workplaces of the

athletic trainers surveyed, there was no significant difference

between heterosexual athletic trainers and gay, lesbian, and

bisexual athletic trainers on the Shortened Workplace Incivility

Scale. Furthermore, the scores on the Shortened Workplace

Incivility Scale did not yield mean scores above the midpoint of the

scale. This suggested athletic trainers surveyed generally did not

encounter incivility in their workplace.

While correlation does not necessarily mean causation, these

findings may suggest a need to revisit the amount of information

on LGBTQIA patients that is required within athletic training

curriculums. Athletic training educators should also consider

including screening tools for their athletic training students

to identify any potential knowledge gaps related to all patient

populations they may encounter. Even if athletic training education

programs are able to include more information about healthcare

issues for LGBTQIA patients, continuing education interventions

should be considered for refreshing knowledge of the definition,

issues, and ways to support LGBTQIA patients and peers. When

these continuing education interventions are created, they should

go through frequent re-evaluation to make sure that they effectively

improve and refresh knowledge of LGBTQIA patient populations

and peers.

A possible limitation of this study was the number of

participants. However, this is a similar limitation that other surveybased

studies on athletic trainers have encountered and may affect

the generalizability of the results when looking to analyze across the

profession [12-14]. Another limitation was that the data gathered

did not allow the authors to determine causation for the findings.

When performing this pilot study, the authors were focused on

determining correlations that warranted further examination in

future studies.

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to use the

LGB-KASH and Shortened Workplace Incivility Scale with athletic

trainers. To this end, future research should examine the causes

of the correlations described in this pilot study. Future research

should also be directed towards examining the impact of lack of

education and knowledge of LGBTQIA individuals and the issues

they encounter on feelings of discomfort and self-consciousness.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study did not find significant differences between heterosexual athletic trainers and gay, lesbian, and bisexual athletic trainers regarding the Hate and Civil Rights subcategories on the LGB-KASH. There were, however, significant differences regarding the Knowledge, Religious Conflicts, and Internalized Affirmation subcategories. Neither heterosexual athletic trainers nor gay, lesbian, and bisexual athletic trainers appeared to experience a high degree of incivility in their workplace. Even though previous studies have suggested the majority of athletic trainers generally have positive attitudes toward LGBTQIA patients, there is still a need for further examination of the attitudes of athletic trainers and other stakeholders toward LGBTQIA athletic trainers.

References

- Crossway A, Rogers SM, Nye EA, Games KE, Eberman LE (2019) Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer athletic trainers: Collegiate Student-Athletes’ Perceptions. Journal of Athletic Training 54(3): 324-333.

- Darr B, Kibbey T (2016) Pronouns and thoughts on neutrality: Gender concerns in modern grammar. Pursuit 7(1): 71-84.

- Nye EA, Crossway A, Rogers SM, Games KE, Eberman LE (2019) Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer patients: collegiate athletic trainers’ perceptions. Journal of Athletic Training 54(3): 334-344.

- Nye EA, Walen DR, Rogers SM, Crossway AK, Winkelmann ZK, et al. (2019) Athletic trainers’ perceptions about collegiate transgender student-athletes’ unfair advantage in sport participation. Journal of Athletic Training 54(6S): S72.

- Walen DR, Nye AE, Rogers SM, Crossway AK, Winkelmann ZK, et al. (2019) Athletic trainers’ perceived competence and educational influences in their ability to care for collegiate transgender student-athletes. Journal of Athletic Training 54(6S): S72-S73.

- Raju D, Beck L, Azuero A, Azuero C, Vance D, et al. (2019) A comprehensive psychometric examination of the Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Knowledge and Attitudes Scale for Heterosexuals (LGB-KASH). J Homosex 66(8): 1104-1125.

- Worthington RL, Becker-Schutte AM, Dillon FR (2005) Development, reliability, and validity of the Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Knowledge and Attitudes Scale for Heterosexuals (LGB-KASH). Journal of Counseling Psychology 52(1): 104-118.

- Di Marco D, Martinez-Corts I, Arenas A, Gamero N (2018) Spanish validation of the shorter version of the workplace incivility scale: An employment status invariant measure. Front Psychol 9: 959.

- Tarihi G, Tarihi K (2018) Workplace incivility: Scale development and validation. Third Sector Social Economic Review 53(2): 433-449.

- Jimenez P, Bregenzer A, Leiter M, Magley V (2018) Psychometric properties of the German version of the workplace incivility scale and the instigated workplace incivility scale. Swiss Journal of Psychology 77(4): 159-172.

- Smidt O, de Beer LT, Brink L, Leiter MP (2016) The validation of a workplace incivility scale within the South African banking industry. South African Journal of Industrial Psychology 42(1): a1316.

- Cage SA, Warner BJ, Gallegos DM, Goza JP, Winkelmann ZK (2020) Perceived and actual knowledge of cupping therapy concepts among athletic trainers in the state of Texas. Research & Investigations in Sports Medicine 6(4): 538-542.

- Yang CW, Yen ZS, McGowan JE, Chen HC, Chiang WC, et al (2012) A systematic review of retention of adult advanced life support knowledge and skills in healthcare providers. Resuscitation 83(9): 1055-1060.

- Schellhase K, Plant J, Rothschild C (2015) Collegiate athletic trainers’ perceived and actual knowledge of therapeutic ultrasound concepts. International Journal of Athletic Therapy and Training 20(5): 43-53.

© 2021 SA Cage. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)