- Submissions

Full Text

Research & Investigations in Sports Medicine

Video Self-Modeling and Collegiate Field Hockey: The Effect of a Self-Selected Feedforward Intervention on Player Hitting Ability

Brad D Foltz1*, Lisa K Denton2 and Jesse Steinfeldt3

1Department of Athletics, Purdue University, USA

2Department of Psychology, State University of New York at Fredonia, USA

3Department of Counseling and Educational Psychology, Indiana University, USA

*Corresponding author: Brad D Foltz, Department of Athletics, Purdue University, Mackey Arena 900 John R Wooden Dr West Lafayette, Indiana, USA

Submission: August 12, 2019;Published: August 19, 2020

ISSN: 2577-1914 Volume7 Issue1

Abstract

The purpose of this study is to test the effectiveness of a Video Self-Modeling (VSM) intervention on the hitting performance of collegiate field hockey players. Using a multiple-baseline single-subject design, 4 female collegiate field hockey players took part in a 3-week VSM intervention following a 1-week baseline measurement period. Each participant watched a personalized VSM video once per day on the device (e.g., computer, smartphone) of their choosing. The 1-minute videos consisted of recordings of each participant’s performances edited to show only the shots that the participant selected as ideal representations of her swing. Measurements of participant performance (e.g., shot accuracy) were taken four times per week during the 3-week intervention phase. Findings of this study may have implications for psychology practitioners in regard to the potential utility of modern technology when delivering VSM interventions. Additionally, the results may provide insight for sport psychology practitioners into the efficacy of VSM interventions with field hockey players.

Keywords: Video self-monitoring; Performance enhancement; Skill acquisition; Single-subject design; Technology

Introduction

The ubiquitous nature of modern technology in everyday life suggests that it is a worthwhile endeavor to explore how technology can enhance psychological service delivery and interventions [1-3]. One specific domain of psychological practice that may benefit from further exploration regarding the use of technology is sport and performance psychology [4,5]. In terms of sport psychology interventions, the use of imagery has been identified as a core performance-enhancement mental skill [5-8] and has been found to be effective in the enhancement of learning, performance, and self-efficacy [8-14].

Video self-modeling (VSM) presents an intersection of modern technology and imagery use that maximizes the similarity between the model and the observer. VSM is similar to imagery in that the subject is seeing him- or herself complete a particular task or skill. However, VSM differs from imagery in that instead of using the subject’s imagination to provide the stimulus, the subject engages in vicarious learning by watching a video of him- or herself completing a non-acquired or underdeveloped behavior [15-18]. VSM itself is different than that of simple review of feedback through video or alternative review methods. Reviewing feedback generally involves a review of all outcomes of an attempted behavior, whether they are adaptive or maladaptive [19]. In contrast, VSM procedures focus the subject’s attention only on representations of him- or herself performing adaptive behaviors [17]. VSM itself is then classified into two interventions categories: positive self-review and feedforward [17,18].

Positive self-review (PSR) is a representation of the best efforts an individual has made on their attempts to complete an objective [17]. The alternative VSM methodology, feedforward, presents representations of behavioral objectives not yet acquired or completed [17]. Feedforward, similar to PSR, represents images of skills already in the subject’s range of ability but reorganized to simulate completion of an uncompleted task or completion of the objective in a new context. VSM utilizes concepts from Bandura’s self-efficacy theory to engage an individual in observational learning in which the subject is both the observer and the observed. Bandura’s [15,16,20] 19 social-cognitive theory of learning is often cited in explanations of how VSM affects an individual’s self-efficacy and, in turn, his or her target behavioral outcomes. In Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy, an individual’s belief in his or her ability to achieve an outcome is believed to be influenced through four sources of learning (i.e., performance accomplishments, vicarious experiences, verbal persuasion, emotional arousal). It has been suggested that all four of these sources of learning may be influenced by VSM interventions; however, it is performance accomplishments and vicarious experiences that are most applicable to VSM [21].

VSM is a form of modeling that provides performance accomplishments that represent mastery information for the subject [17,19]. Presenting the subject with VSM interventions may contribute to the individual feeling that he or she has developed mastery of the target behavior [19]. This, in turn, could potentially enhance the subject’s sense of self-efficacy for the objective behaviors and increase the prospects of the subject successfully completing the behavior.

The second category, vicarious experiences, consists of learning though the observation of others performing a task. Model-observer similarity has been proposed as a means to explain the efficacy of vicarious experiences in VSM interventions [19,21]. In essence, it is hypothesized that an observer will have greater increases in performance and/or self-efficacy when he or she judges the model being observed as similar to him- or herself.

VSM has shown a great deal of success as an intervention for social and behavioral skill development [17,22,23]. In contrast, research on VSM use in sport has lagged behind that of other domains and has produced mixed results [24-28]. The scarcity and equivocal results of studies utilizing VSM in sport suggest that VSM as a sport psychology intervention is in need of further exploration. Munroe-Chandler & Morris [5] assert that research on the effective use of modern technology as a tool for imagery interventions should be a priority within sport psychology literature. The current study will address the suggestions of Munroe-Chandler & Morris [5] by utilizing commonly available technology (e.g., iPhone) and software (e.g., YouTube) to engage student athletes in a VSM intervention. The results of this study could provide further insight into the utility of VSM in an unstudied context (i.e., collegiate field hockey) as well as the utility of modern technology to deliver VSM interventions. The results of this study could be used by current sport psychology practitioners to inform their delivery of imagery interventions with athletes. In addition, the results may serve to provide further insight into the potential utility of modern technology as a tool for psychological intervention.

Method

Participants

The study utilized a mixed-methods multiple-baseline single-subject design. Participants in the study were four volunteers recruited from an NCAA Division I collegiate field hockey team. Participants were female student-athletes between the ages of 18 and 24. Participants were recruited through an in-person presentation of the proposed study’s purpose and methodology prior to a regularly scheduled team meeting. In an effort to maximize the internal validity of the study, priority for participation was given to underclassmen (e.g., freshman, sophomores), because underclassmen student-athletes may have had less instruction and practice with the performance task (e.g., hitting) than their upperclassmen teammates.

Equipment

All recordings of the athletes for creation of the feedforward videos, and performance recordings, were done with a Sony Handicam. During the intervention portion of the study, the Sony camcorder recorded from a stationary position behind each participant with direct view of the goal. All performance recordings were reviewed by the investigator to validate recorded shot accuracy scores. Shot velocity was recorded using a Bushnell velocity speed gun.

Task

On each of the six performance days, participants were asked to take a total of 12 shots on goal from the top of the scoring circle. Each participant completed two full rotations of the performance task on each day with an approximately 5- to 10-minute break in between performances. Performance on this task was evaluated through shot accuracy. In addition, shot velocity was recorded to assess changes in effort that may influence performance (e.g., reduction in shot velocity in order to maximize control and accuracy of a shot).

Procedure

Participants met with the investigator twice per week during their participation in the study. During each meeting, the participants completed the performance task twice, providing a total of two completed performances to establish their baselines of performance. There was a minimum of five minutes between each performance on the meeting days and one day between each meeting. During each performance throughout the baseline phase, every shot taken was recorded for use in creating each participant’s individual Ffwd recording.

Due to unforeseen circumstances (e.g., participant recovery from injury, changes in class schedules) not all participants were able to begin the baseline phase of the study at the same time. Given the inability to begin the baseline measurement at the same time, a true staggered introduction of the intervention was not possible. Instead the subjects were paired and had the VSM video introduced at separate points in an effort to provide a contrast in the effect the intervention had while their paired subject was still completing the baseline phase (Table 1).

Table 1: Participant performance schedule.

Note: B: Baseline Performance; I: Intervention Performance

Following the establishment of each participant’s baseline scores, the two video recordings of each shot taken during the baseline phase were uploaded to the video-sharing website YouTube; one video was comprised of all recordings made from in front of the participant, and the second consisted of footage taken from behind the participants while performing. Each participant received a private web address to view her raw performance footage. Each participant was asked to identify the six best representations of her swing from the footage taken from both in front of and behind the participant. The investigator edited these selected swings, altering the camera angle from front to back on each swing, in with footage of each target being struck accurately. Thus, the edited video was a representation of the subject’s self-selected swings with outcomes (i.e., 100% shot accuracy) greater than what they currently were able to accomplish. The completed Ffwd videos were approximately one minute in duration. In addition, each participant was asked to select a song that they felt would facilitate their engagement and concentration on the video during the intervention phase. Each participant’s selected song was inserted to replace the audio of each swing, with only the sound of the ball striking the target remaining in the completed Ffwd video.

The completed Ffwd recordings were uploaded to YouTube. In order to maintain confidentiality, each participant was provided with a private, unlisted web address to her personal Ffwd recording. Participants were then instructed to view the recordings daily throughout the intervention phase using a device of their choosing (e.g., smartphone, tablet, laptop). Leaving device selection up to the participants was done to maximize the ease of access and, subsequently, potential adherence to the intervention. Adherence to the intervention was assessed through weekly social validity self-reports from the participants.

The intervention phase of the study lasted a total of three weeks. Participants were instructed to review their Ffwd videos daily. Participants met with the investigator twice per week during the intervention phase and completed the performance task twice per meeting for a total of four complete performances per week. Given the repetition the participants will have with the performance measures, variance in their performance may be influenced by practice effects [29]. A minimum of one day between each meeting, as well as a five- to ten-minute rest period between performances was required, in an effort to minimize practice effects. Following the completion of the 3-week intervention phase, participants also completed a brief semi-structured post-intervention interview.

Measures

Performance: The student-athletes’ performance on the field hockey hitting skill was assessed based on the percentage of accurate shots taken per performance. In addition, shot velocity was measured to assess for any changes in effort (e.g., reduction in hitting force to increase control of shot trajectory) that may influence the validity of the participants’ performance data. The measures of performance were derived through consultation with the coaching staff of the field hockey team from which participants were drawn.

The accuracy performance measure was assessed via the 12 shots on goal taken from the top of the scoring circle in each performance. The ball was placed at the top of the scoring circle, which is 16 yards from the goal cage. The goal itself is 12 feet wide. Within the goal, four 1-foot by 1-foot steel targets were placed equidistant along the baseboard with a 32-inch gap between each target. The targets were labeled with numbers one through four from left to right along the baseboard.

Shot accuracy was assessed by prompting the participants to take three shots on each of the four targets randomly identified by the investigator. Randomization of the target zones was done in an effort to minimize practice effects [29]. Each shot that struck the directed target was scored as a hit. Any shot taken that did not hit the directed target was scored as a miss. In addition, the velocity performance measure was assessed using a velocity radar gun for speed of travel following contact. The velocity measurements were then averaged to provide a metric for comparing overall shot speed changes.

Social validity: The assessment of social validity is an important criterion to consider when evaluating the outcome of an intervention [30-33]. Social validity provides insight into the subjective evaluation and acceptance of an intervention by the consumers of said intervention [32]. Social validity encompasses three primary evaluative questions about an intervention: a) Do the goals of the treatment have social significance to the consumer?, b) Are the intervention procedures deemed appropriate and acceptable by those that utilize the intervention?, and c) Are the outcomes of the intervention important within the social context it was designed to effect [31,32]? Social validity for this study was assessed using an eight-item questionnaire asking the participants to rate their agreement with statements regarding their experiences with the VSM videos in the past week. The questions utilized a 4-point Likert scale with responses ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Items included “The video self-modeling activity has interfered with my normal practice routine” “I believe the video self-modeling activity is beneficial to me” and “The video self-modeling activity is easy to utilize”.

Post-intervention Interview: Upon completion of their participation in the VSM intervention phase, participants were interviewed by the first author regarding the subjective evaluations of the participants’ experiences with the intervention. The interviews took place using a semi-structured format and focused on participant perceptions of the effect and utility of the VSM interventions. The interviews were recorded using a digital audio recorder and stored using de-identified coding to protect each subject’s confidentiality. Following completion of the interviews, the recordings were transcribed and reviewed to identify general themes present in the participants’ experiences with VSM.

Data analysis

As is common in single-subject design research, the results of this study were evaluated through visual analysis of graphically plotted data collected throughout the baseline and interventions phases [30,34]. The magnitude of changes in performance was assessed through comparison of the baseline and intervention performance means. Comparison of the means provides insight into whether or not the intervention contributed to meaningful and consistent changes in participant scores. Immediacy of effect was evaluated through analysis of the number of performances following the introduction of the intervention prior to scores exceeding each subject’s baseline scores [32,35]. The immediacy of change in the data points provides information from which inferences may be made regarding the change in outcome measures being affected by the introduction of the VSM intervention [35]. A trends analysis was conducted through comparison of performance trend lines between each participant’s baseline- and intervention-phase scores. The trends analysis provides information regarding the potential direction of future changes on the outcome variable and shows systematic increases or decreases in performance over time [30,32].

Percentage of data points exceeding the median (PEM) is used to evaluate the reliability of the intervention across participants and to provide an estimate of effect sizes [36]. PEM has been identified as an improvement over previous measures of effect in single subjects designs as it is less susceptible to floor or ceiling effects [36]. PEM provides a percentage of data points during the intervention phase that exceed the median data point of the baseline phase. PEM provides a score ranging from 0 to 1 and can be interpreted the same as an effect size [36]. PEM scores are interpreted using the criterion for evaluation outlined by Scruggs, et al. [37] (e.g., PEM of .9 to 1 is highly effective treatment, PEM of .7 to .9 is moderately effective treatment, and PEM of .7 or less is mildly to not effective treatment).

The post-intervention interviews were analyzed using a constant comparative method [38]. The constant comparative method has been developed as an extension of grounded theory. Using the constant comparative method, the lead investigator compared prominent themes from each interview in an effort to derive categories and their inherent properties [38].

Results

Performance

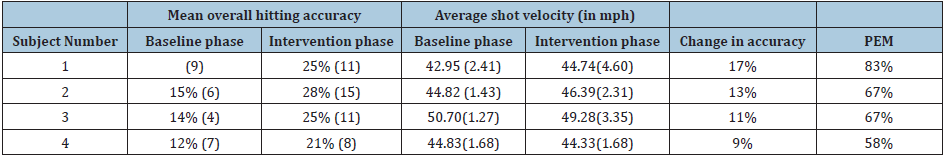

Table 2: Participant performance summaries and PEM scores.

Note: Standard deviations are presented in parentheses. PEM: Percentage of data points exceeding the median.

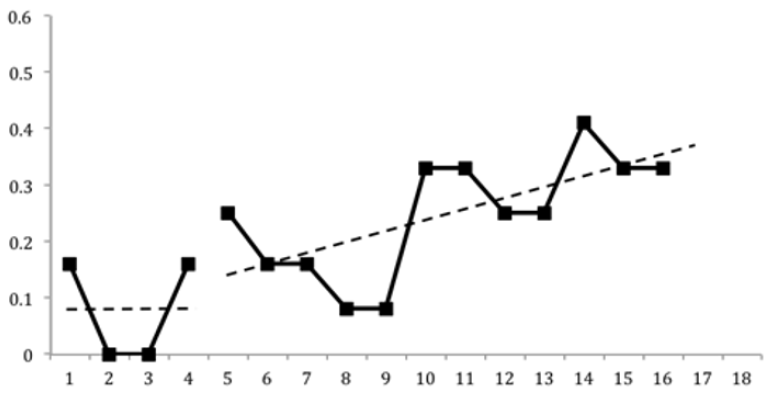

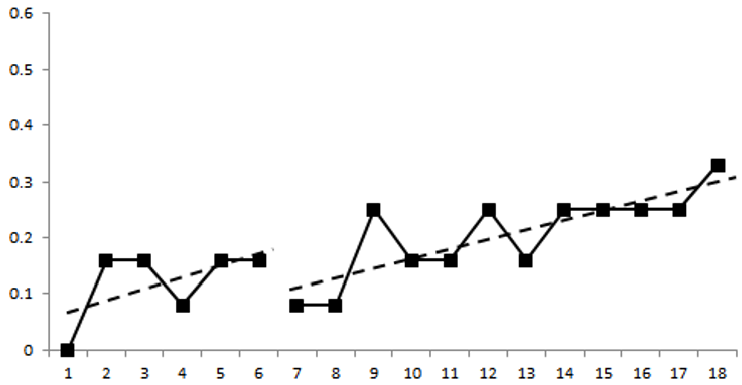

Table 2 provides PEM scores and a summary of performance for all four subjects. Subjects 1, 2, 3, and 4 demonstrated improvements in accuracy of 17%, 13%, 11%, and 9%, respectively, after introduction of the VSM intervention. However, trends in performance changes vary by participant. Subject 1 demonstrated an immediate increase in hitting accuracy during her first performance of the intervention phase. Her final accuracy total during baseline was 16%, while her first performance during intervention was 25%. However, following her first intervention performance, her next four performances produced accuracies within the range of her baseline scores. It was not until her sixth performance during the intervention phase that her accuracy rose above her baseline range of scores and remained above her baseline score for the remainder of the intervention phase. During baseline, Subject 1’s performances demonstrated no trend (m = 0; R2 = 0). Following the introduction of the Ffwd intervention, Subject 1’s performances demonstrated an accelerating slope (m = .02; R2 = .43). See Figure 1 for a graphical representation of trend lines.

Figure 1: Subject 1 trend lines. Hitting accuracy (percent of targets hit) by hitting task session number.

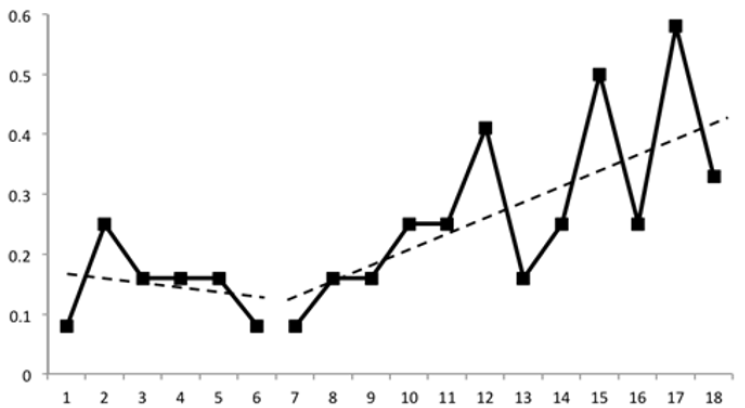

Unlike Subject 1, Subject 2 did not experience an immediate increase in hitting accuracy after beginning the intervention phase. Her first baseline performance produced accuracy (8%) equivalent to her final baseline performance. Her first intervention performance was the lowest accuracy total for the remainder of the intervention phase, as her second and third performances improved to 16%. Her fourth and fifth performances matched her peak baseline performance; however, it was not until her sixth intervention performance that her hitting accuracy exceeded the peak accuracy of her baseline phase. Subject 2 has a slight downward trend in performance during baseline (m = -.01; R2 = .05). See Figure 2. In contrast, her intervention performances followed a more positive trend (m = .03; R2 = .48).

Figure 2: Subject 2 trend lines. Hitting accuracy (percent of targets hit) by hitting task session number.

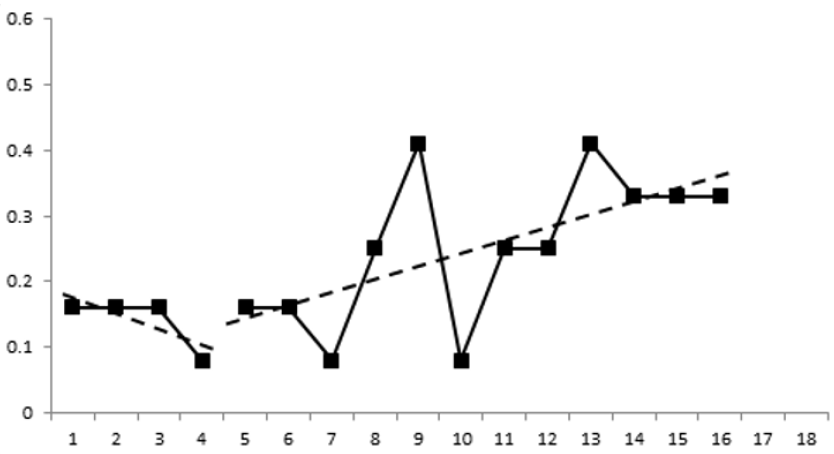

Subject 3’s final hitting accuracy score during baseline was 8%, and her first intervention performance produced an accuracy of 16%. Her accuracy scores fell within the range of her baseline performances for her first three intervention performances. Subject 3 exceeded her peak baseline accuracy on her fourth intervention performance with an accuracy of 25% and a high of 41% on her fifth and ninth performances. Similar to Subject 2, Subject 3’s performances followed a decreasing trend during baseline (m = -.02; R2 = .6). Her performance trend during intervention followed an accelerating slope (m = .02; R2 = .39). See Figure 3.

Figure 3: Subject 3 trend lines. Hitting accuracy (percent of targets hit) by hitting task session number.

Subject 4’s accuracy fell from 16% on her final two baseline performances to 8% on her first two performances immediately following the introduction of the VSM intervention. Upon her third performance, her accuracy exceeded her peak baseline performance with an accuracy of 25%. Subject 4’s accuracy scores remained at or above her peak baseline scores for the remainder of her participation. Subject 4’s baseline performance produced a positive trend (m = .02; R2 = .33). Her intervention performances also followed a positive trend with a slope similar to her baseline performances (m = .02; R2 = .65). Figure 4 provides trend lines for subject 4.

Figure 4: Subject 4 trend lines. Hitting accuracy (percent of targets hit) by hitting task session number.

Social validity

Subjects completed the social validity questionnaire for each of the three weeks they utilized the Ffwd intervention. They also indicated the number of times per week of the intervention that they watched their video. The mean number of days per week during the intervention phase that the Subjects 1, 2, 3, and 4 watched their videos were 3.67 (SD=5.77), 3 (SD=0), 6.33 (SD=1.15), and 7 (SD=0), respectively.

On each of the three weeks of the intervention, Subjects 1 and 3 both indicated that they disagreed that the self-modeling activity interfered with their normal practice routine. This is in contrast to the other subjects. Subject 2 indicated that the activity interfered with her normal practice in weeks one and three, but not in week two of the intervention. Subject 3 indicated no interference in weeks 1 and 2, but ‘strongly agreed’ that the activity interfered with her routine in week 3. Overall, responses to the remaining prompts on the social validity questionnaire indicate a positive reception of the Ffwd intervention for all subjects.

Post-intervention interviews

The lead investigator reviewed the manuscripts of the post-intervention interviews conducted with each subject using a constant comparative method [38]. Through utilization of the constant comparative method, nine themes were derived within three primary categories (a) skill development, (b) moderators of Ffwd effectiveness, and (c) recommendations for future.

Skill development: The first category, skill development, addressed how the subjects felt the Ffwd intervention had helped them improve as an athlete. Three themes emerged within the skill development category: (a) hitting, (b) self-confidence, and (c) imagery. The first theme within the skill development category, hitting, involved the subjects feeling as though their hitting skill had improved through utilization of the Ffwd intervention. In discussing how her hit had improved through watching the Ffwd video, one subject stated, “I thought that I was getting much better, like the hitting was getting a lot better.” Another subject stated, “I think it definitely made my hit better just because, like, I could see it. I think it helped me adjust small things in my hitting that actually helped hit targets better.”

The second theme of responses within the skill development category revolved around the subjects feeling as though their self-confidence had improved through using the Ffwd video. When speaking about her experience watching the Ffwd video during the study, one subject shared, “I know, me personally, my hits got so much better by the end, and it definitely was a confidence booster.” Another subject expressed that she felt watching herself perform well on the Ffwd video helped develop her belief that she could perform well. Specifically, she stated, I struggle with my mental side of the game, especially like the negativity. So trying not to critique myself and, you know, look at the positives was really difficult for me at first...Especially watching the ball hit the [targets], I was like “Oh, I really didn’t hit the (targets).” This was first time I saw it...I thought it was pretty good, you know, to have a visual of you hitting the (targets) and you finally start to get it ingrained in your head “yes you can do it.”

Imagery, the third theme within the skill development category, involved the subjects sharing that they felt the Ffwd video enhanced their ability to engage in imagery use. One comment made by a participant regarding imagery during the interviews was, “I can visualize it in my head before I hit, and I get a more clear picture.” Another subject stated, After watching the video, like, I saw that I could do that so I imagined myself doing the same as on the video. I was better after watching the video. Before I hit the ball I could visualize the exact place that I wanted to hit.

Moderators of Ffwd effectiveness: The second category reflected the characteristics of the Ffwd intervention that facilitated the intervention’s effectiveness. Within the moderators of Ffwd effectiveness category, 4 themes emerged (a) ease of use, (b) audio, (c) unfamiliarity with Ffwd, and (d) self-selection. The first theme, ease of use, reflected the subjects’ favorable view of the Ffwd interventions usability during the study and in the future as part of their training routines. One subject stated, “I think it was like, the timing of it was good, it was short, like quick, easy to watch.” Another subject shared a similar perspective:

Being able to watch it online or download it was good. Just watching it and just taking five minutes, not even, like two minutes a day because I downloaded it. So I could just watch it any time I wanted, whether it was on my phone or on my computer. So just taking two minutes to watch it, like, I’ll probably still watch it to be quite honest.

The second theme in the moderators category addressed the subjects’ view of the audio that accompanied their videos and how the audio enhanced their experiences with the Ffwd intervention. When talking about the music she selected to accompany her video, one participant stated, “I picked the song I listened to before every game so, like, with the video I’m already in that mentality of, you know, it’s game day get ready.” Another participant shared that she felt the music she chose for her video helped her evoke “two separate feelings, being like calm, and at the same time, just that very distinct, like, game day type feeling.”

Unfamiliarity with Ffwd addressed the feeling that it took time for the participants to accommodate to the individual nature and focus of the Ffwd videos before they could best utilize the intervention. One subject stated that it “was like kind of weird at first to accept the fact that, like, ‘alright just watch the video,’ but that got better as we went.” Another subject stated, It was a little weird at first, but I kind of liked it because you get to see a lot of things that you don’t really get to notice every other day that you’re hitting. It was just weird in a way, like, I never watched film like that of myself just hitting, like constant reps.

The fourth theme, self-selection, reflected the participants’ feelings regarding choosing the hits to be made into their Ffwd intervention videos. When speaking on selecting her hits for the video, one subject stated, I thought it was useful because then, you know, no one knows your hit better than yourself. So, I feel like, you know, picking your own hit, everyone hits differently you know. I hit completely different from (Name Redacted), you know, she probably has the fastest hit on the team. But like (Name Redacted), her accuracy like definitely improves throughout the experiment, so I mean like, everyone is so different so you picking your own hit was definitely beneficial because you know which way you hit. You know what it looks like and what’s most effective for you, so I thought it was good that we got to pick our own.

Recommendations for future. The third category, recommendations for future, is comprised of thoughts the subjects shared regarding how to make future use and study of Ffwd more effective. Within the recommendations for future category, two themes emerged: (a) measure sensitivity and (b) use of Ffwd with different skills. The first theme, measure sensitivity, reflected the thoughts the subjects had regarding performance measure for the study not fully reflecting their improvement in performance. When talking about her thoughts regarding the study, one subject stated, “I would say one thing is either making bigger targets or somehow we could see improvement, like getting closer to the target, or some way to measure that, because there were some where I got much closer.” Similarly, another subject stated, You know, the first round everyone is like so far off, but as we went everyone, like, slowly gets closer and closer and closer to the target. It’s not that we were not improving, but it’s just that we are not hitting the target, but we are getting closer to it.

The second theme, use of Ffwd with different skills, represented the participants’ suggestions that Ffwd videos could be effective for developing field hockey skills beyond just hitting. One subject shared that she thought it would be good to use Ffwd with “not only hitting but sweeping, for me I can hit better, but sweeping is complicated.” Another subject stated, “Maybe like filming drills, or something like that. Like chipping drills, I don’t know if you’ve ever seen our chipping drills, but I think this video thing would be perfect for something like that.”

Discussion

Performance

This study intended to address the gap in VSM literature by examining the effectiveness of an Ffwd video self-modeling intervention on the hitting performance of collegiate field hockey players. Upon visual inspection of the participants’ performance data, the results of this study provide mixed support for the Ffwd intervention’s impact on hitting performance. All four subjects demonstrated an increase in their average hitting accuracy following the introduction of the Ffwd videos. In addition, the results of the post-intervention interviews provide additional support for the intervention’s positive impact on the subjects’ hitting skills. A theme that emerged within the skill development category represented the participants’ perspective that their hitting skills had improved. This combination of results—the improvement in average hitting accuracy from baseline to intervention and self-perception of skill improvement—provides support for the Ffwd intervention as a skill development tool.

However, further inspection of the performance data presents contrasting evidence supporting the efficacy of the Ffwd intervention. All four subjects experienced an ascending trend in performance following the introduction of the Ffwd intervention. During baseline measurement, Subjects 1, 2, and 3 produced either no trend (Subject 1) or a descending trend (Subjects 2 and 3). The flat and descending performance trends during baseline help provide evidence that the performances of Subjects 1, 2, and 3 were not improving through practice effects or familiarity with the performance task. However, Subject 4 contrasted the other participants’ data by producing an increasing trend in performance for both study phases. Subject 4’s positive trends in both phases potentially challenge the support for the notion that the intervention alone contributed to improving trends in performance. Subject 4’s responses during the post-intervention interview may provide insight into why her performance trends differed from the other three subjects. Subject 4 disclosed during her interview that she had been injured prior to her participation in the study and that her first performance coincided with her first day being medically cleared to return to practice. Subject 4 had not been practicing or playing regularly prior to her first performance, and she produced an accuracy of 0.00% during her first attempt at the performance task. Following her first attempt at the performance task, Subject 4’s remaining baseline performances produce a trend with no slope. It is possible that the final five performances during the baseline phase are more representative of Subject 4’s actual skill level during baseline than the first performance, where she may have been acclimating to the hitting skill. While practice effects cannot be fully ruled out in explaining the increasing slope of performance while using the Ffwd intervention for each of these subjects, following flat or descending slopes of performance during baseline lends support for the effectiveness of the Ffwd intervention as a skill development tool.

Only 1 subject, Subject 1, had a PEM (83%) that was within the moderately effective range defined by Scruggs, Mastropieri, Cook, and Escobar (1986). The PEM scores of Subject 2 (67%), Subject 3 (67%), and Subject 4 (58%) all fell within the mild to questionable effect range. The PEM values produced by the participants appear to reflect a lack of consistency in the intervention phase performances. So, while the overall average accuracy and trend in performances improved for each participant, the performances still produced variability in outcome. It should be noted that each subject produced her peak performance on the hitting task during the intervention phase of the study. This result may indicate that the intervention may contribute to increase in peak performance but not necessarily lead to short-term improvements in consistency of performance.

The latency of the improvement in performance scores makes it difficult to relate the improvements in performance to the Ffwd intervention alone. All four participants produced improvements in performance by their second week of using the Ffwd intervention, however, the delay in performance improvements could be a reflection of skill development through familiarity and practice with the performance task rather than due to the intervention itself. Law & Ste-Marie [39] postulate that self-modeling interventions may be most effective with individuals who would be classified as novices in respect to the skill being developed. This phenomenon has been supported in previous VSM literature, which shows that novice-level performers experience greater performance gains [28,40] than do performers of intermediate or elite skill level [19,39,41]. The results of this study may further support the contention of Law and Ste-Marie. Given the advanced skill level of the participants, any improvement in skill may have been minimal compared to what a novice may have experienced upon introduction of the intervention. Thus, the delay in performance change in this study may represent the relatively small room for immediate improvement in skill for the participants, given the elite level of skill already in their repertoire.

Results of the post-intervention interviews also may account for the delay in performance improvements. A theme within the moderators category, unfamiliarity with Ffwd, spoke to the subjects feeling that it took time to become comfortable with the intervention. Dowrick [18,42] explains that Ffwd presents opportunities for the subject to learn from a yet-to-be-obtained future level of performance. Conceivably, the subjects in this study initially found it difficult to engage in prospection, and not until they acclimated to the MTT were they able to fully experience the benefits of the Ffwd intervention. The delay in change in performance aligns with the results of previous literature on VSM use in sport, in which improvements in performance peaked following several weeks of exposure to the intervention [24,25]. The results of this study, as well as previous VSM literature, suggest that perhaps VSM interventions in sport may represent a skill domain that necessitates an adjustment period prior to the intervention contributing to skill improvement. Such domains should be taken into consideration when evaluating the immediacy of change in single-subject designs [32].

Social validity

The social validity of the Ffwd intervention was evaluated through qualitative analysis of the descriptive data obtained from the social validity questionnaires and the post-intervention interviews. The data obtained suggest that the Ffwd intervention used in this study had high social validity. Positive attitudes toward an intervention’s efficacy and ease of use can improve the likelihood of treatment adherence and treatment satisfaction, as well as help sport psychology practitioners gain entry with athletes and athletic organizations [43-46]. The positive appraisal of the Ffwd intervention was not universal for all prompts. Two subjects indicated on the social validity questionnaire that they found the intervention interfered with their normal practice routines.

The data gathered through the social validity questionnaires also provided information regarding how often each participant watched her video. Of potential interest to future research and practitioners is that regularity or number of viewings of the Ffwd videos did not appear to influence the performance results. Subjects 1 and 2 watched their videos less often than Subjects 3 and 4, yet all participants experienced gains in performance. This result could indicate that increased exposure to the intervention may not lead to greater skill gains. It could also lend doubt to the efficacy of the intervention, as similar gains occurred in all participants, independent of number of viewings, which may be a factor of potential practice effects.

Limitations

Limitations of the design and methodology of this study should be considered when interpreting the presented results. A primary limitation of the current study was the inability to utilize a full multiple-baseline design. This study’s inability to begin all subjects’ participation at the same time makes it more difficult to attribute improvements in performance to intervention and not extraneous variables. Sample size, and the use of a convenience sample, is also an important limitation to consider when evaluating the results of this study. Due to a limited sampling population (i.e., field hockey athletes) it was not possible for this study to follow the recommendation of Feltz and colleagues [24] to use a large sample size. In addition, there may be selection bias among the subjects in this study based on their voluntary desire to participate.

Results of the post-intervention interviews also identified another potential limitation of this study. A theme emerged in which the participants felt the performance measure may not have been sensitive enough to measure incremental performance improvements. Task performance was assessed through a binary system of shots taken at a target only being scored as a hit or a miss. This means of measurement was not able to account for an increase in accuracy the subjects may have experienced even when they may not have hit the target. Future assessment of an Ffwd intervention of a similar skill may benefit from devising a mechanism of performance measurement that is able to account for such incremental improvements, especially when working with elite-level athletes whose skill level may only experience marginal improvement as compared to that of a novice.

The self-report nature of the data collected may present another possible limitation for the study. The methodology of this study relied on the subjects’ self-reports to assess adherence to the Ffwd intervention, thus it is possible that the data reported on the social validity questionnaire do not accurately reflect how often and in what quantity the participants may have watched their videos.

Possible external factors must also be considered regarding the participants’ performance data. It is possible that external factors such as injury, illness, academic stressors, practice effects, and instruction from coaches, among others, may have influenced the hitting performances of the subjects. The potential effects of such extraneous variables should be considered when interpreting the results of this study.

Implications for Practice and Future Directions

The results of this study provide moderate support for the use of Ffwd as a field hockey performance enhancement intervention. The data gathered were not able to provide unequivocal support, as latency in improvement and PEM scores for three of the four subjects were in the questionable effect range. However, the Ffwd intervention was evaluated by the participants as having a high degree of social validity. Contrasting support for VSM as a performance enhancement intervention may reflect the possibility that VSM is more effective with continuous skills as compared to discrete skills [39].

The subjects identified three additional moderators that enhanced their use of the Ffwd intervention. Both the length and accessibility (e.g., ability to access the videos online) were cited as facilitators of the interventions effectiveness and the participants’ likely future utilization of the intervention in training routines. The subjects felt positively about the ease of use of the intervention and even expressed interest in continuing to use their videos at the end of the study. The second moderator the subjects identified in their interviews was that the audio playing during the video aided in its effectiveness. Imagery that is both vivid and evokes a positive emotional response is most effective in aiding performance [8]. The participants in this study suggested that they chose music for their Ffwd videos that elicited a similar mental state as they would experience prior to a game. This result suggests that the audio accompanying an Ffwd intervention should be given consideration when developing the intervention for use in different contexts, with different skills, and with different outcomes in mind. The third potential moderating factor to consider for future Ffwd use was the subjects’ view of self-selecting their hits for the videos. The subjects expressed that by choosing their own hits to include, they were better able to evaluate the quality of the hits included than that of someone unfamiliar with their hits. This result does not necessarily lay claim that only the subject should select the clips to include in a VSM video, however, it may point to the benefit of getting an opinion of an outsider with more expertise in the skill to select the clips to include. It may be beneficial for practitioners and future research to explore the connection between self-selection and Ffwd effectiveness.

The participants in this study recommended that the VSM intervention used would be beneficial for several different skills within their sport. Of particular interest, the subjects identified team skills that may benefit from the intervention beyond the individual skills VSM most often focuses on. Research into the utility of Ffwd interventions on a team level could be valuable in opening up potential avenues for VSM use in additional sport and performance psychology domains.

References

- Hansen JC (2012) Contemporary counseling psychology. Oxford University Press, New York, USA.

- Mallen MJ, Vogel DL, Rochlen AB (2005) The practical aspects of online counseling: Ethics, training, technology, and competency. The Counseling Psychologist 33(6): 776-

- Vodanovich S, Sundaram D, Myers M (2010) Digital natives and ubiquitous information systems. Information Systems Research 21: 711-723.

- Ives JC, Straub WF, Shelley GA (2002) Enhancing athletic performance using digital video in consulting. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 14(3): 237-

- Munroe-Chandler K, Morris T (2011) Imagery. In: Morris T & Terry P (Eds.), The new sport and exercise psychology companion, Fitness Information Technology, Morgantown, West Virginia, USA, pp. 275-308.

- Cumming J, Hall C, Shambrook C (2004) The influence of an imagery workshop on athletes’ use of imagery. Athletic Insight: The Online Journal of Sport Psychology 6.

- Morris T, Spittle M, Watt AP (2005) Imagery in sport. Human Kinetics, Champaign, Illinois, USA.

- Murphy SM (2005) Imagery: Inner theater becomes reality. In: SM Murphy (Ed.), The Sport Psych Handbook. Human Kinetics, Champaign, Illinois, USA, pp. 127-

- Barr KA, Hall CR (1992) The use of imagery by rowers. International Journal of Sport Psychology 23(3): 243-

- Callow N, Hardy L, Hall C (2001) The effects of a motivational general-mastery imagery intervention on the sport confidence of high-level badminton players. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 72(4): 389-

- Driskell JE, Copper C, Moran A (1994) Does mental practice enhance performance? Journal of Applied Psychology 79(4): 481-492.

- Feltz DL, Landers DM (1983) The effect of mental practice on motor skill learning and performance. A meta-analysis. Journal of Sport Psychology 5(1): 25-57.

- Guillot A, Genevois C, Desliens S, Saieb S, Rogowski I (2012) Motor imagery and ‘placebo-racket effects’ in tennis serve performance. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 13(5): 533-

- Pain MA, Harwood C, Anderson R (2011) Pre-competition imagery and music: The impact on flow and performance in competitive soccer. The Sport Psychologist 25(2): 212-

- Bandura A (1977) Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev 84(2): 191-215.

- Bandura A (1986) Social foundation of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, Prentice-Hall, New Jersey, USA.

- Dowrick PW (1999) A review of self-modeling and related interventions. Applied and Preventative Psychology 8: 23-39.

- Dowrick PW (2012a) Self-model theory: Learning from the future. WIREs: Cognitive Science 3: 215-230.

- Ram N, McCullagh P (2003) Self-modeling: Influence on psychological responses and physical performance. The Sport Psychologist 17(2): 220-241.

- Bandura A (1997) Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Henry Holt, New York, USA.

- McCullagh P, Weiss MR (2001) Modeling: Considerations for motor skill performance and psychological responses. In: RN Singer, et al. (Eds.), Handbook of sport psychology (2nd edn), Wiley, New York, USA, pp. 205-238.

- Bellini S, Akullian J, Hopf A (2007) Increasing social engagement in young children with autism spectrum disorders using video self-modeling. School Psychology Review 36(1): 80-90.

- Buggey T, Ogle L (2012) Video self‐ Psychology in the Schools 49(1): 52-70.

- Feltz DL, Short SE, Singleton DA (2008) Short communication B: The effect of self-modeling on shooting performance and self-efficacy with intercollegiate hockey players. In: Simmons MP & Foster LA (Eds.), Sport and Exercise Psychology Research Advances Hauppauge, Nova Biomedical Books, New York, USA, pp. 9-18.

- Franks IM, Maile LJ (1991) The use of video in sport skill acquisition. In: Dowrick PW (Ed.), Practical guide to using video in the behavioral sciences. Wiley, New York, USA, pp. 231-243.

- Hall EG, Erffmeyer ES (1983) The effect of visuomotor behavior rehearsal with videotaped modeling on free-throw accuracy of intercollegiate female basketball players. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 5(3): 343-346.

- Nelson J, Czech DR, Joyner AB, Munkasy B, Lachowetz T (2008) The effects of video and cognitive imagery on throwing performance of baseball pitchers: A single subject design. The Sport Journal 11.

- Starek J, McCullagh P (1999) The effect of self-modeling on the performance of beginning swimmers. The Sport Psychologist 13: 269-287.

- Shaughnessy JJ, Zechmeister EB, Zechmeister JS (2000) Research methods in psychology (5th edn), McGraw-Hill, New York, USA.

- Alberto PA, Troutman AC (2009) Single-subject designs. In: Alberto PA & Troutman AC (Eds.), Applied Behavioral Analysis for Teachers (8th edn), Upper Saddle River, Pearson, New Jersey, USA, pp. 115-167.

- Carter SL (2010) The social validity manual: A guide to subjective evaluation of behavior interventions. Maryland Heights, Academic Press, USA

- Kazdin AE (2011) Single-case research designs: Methods for clinical and applied settings. Oxford University Press, New York, USA.

- Wolery M, Harris SR (1982) Interpreting results of single-subject research designs. Phys Ther 62(4): 445-

- Horner RH, Carr EG, Halle J, McGee G, Odom S, et al. (2005) The use of single-subject research to identify evidence-based practice in special education. Exceptional Children 71(2): 165-

- Kratochwill TR, Hitchcock J, Horner RH, Levin JR, Odom SL, et al. (2010) Single-case designs technical documentation. What Works Clearinghouse.

- Ma H (2006) An alternative method for quantitative synthesis of single-subject researches: Percentage of data points exceeding the median. Behavior Modification 30(5): 598-617.

- Scruggs TE, Mastropieri MA, Forness SR, Escobar C (1986) Early interventions for children with conduct disorders: A quantitative synthesis of single-subject research. Behavioral Disorders 11(4): 260-271.

- Merriam SB (2009) Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, California, USA.

- Law B, Ste-Marie D (2005) Effects of self-modeling on figure skating jump performance and psychological variables. European Journal of Sport Science 5(3): 143-152.

- Dowrick PW, Dove C (1980) The use of self-modeling to improve the swimming performance of spina bifida children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis 13: 51-56.

- Winfrey ML, Weeks DL (1993) Effects of self-modeling on self-efficacy and balance beam performance. Perceptual and Motor Skills 77(3): 907-913.

- Dowrick PW (2012b) Self-modeling: Expanding the theories of learning. Psychology in the Schools 49(1): 30-41.

- Cheney CD (1996) Medical nonadherance: A behavioral analysis. Plenum, New York, USA.

- Fifer A, Henschen K, Gould D, Ravizza K (2008) What works when working with athletes. The Sport Psychologist 22(3): 356-377.

- Hundt NE, Armento MEA, Porter B, Cully JA, Kunik ME, et al. (2013) Predictors of treatment satisfaction among older adults with anxiety in a primary care psychology program. Eval Program Plann 37: 58-63.

- Taylor S, Abramowitz JS, McKay D (2012) Non-adherence and non-response in the treatment of anxiety disorders. J Anxiety Disord 26: 583-589.

© 2020 Brad D Foltz. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)