- Submissions

Full Text

Research & Investigations in Sports Medicine

Inclusion of Cupping Therapy in CAATE Accredited Athletic Training Programs Curriculums

S Andrew C1,2*, Brandon W2,3, David M3, Diana G1, Lynzi W4 and Julie G5

1University of Texas at Tyler, USA

2University of North Carolina, Greensboro, USA

3Grand Canyon University, USA

*Corresponding author: S Andrew C, University of Texas at Tyler, USA

Submission: July 28, 2020;Published: August 19, 2020

ISSN: 2577-1914 Volume6 Issue5

Abstract

To date, there appears to be a lack of research on the inclusion of cupping therapy in formal athletic training education. Previous studies have suggested that most athletic trainers use cupping therapy in their clinical practice but exhibit a gap in their perceived and actual knowledge of the modality. However, these studies did not evaluate whether the participants had participated in cupping therapy education within their professional curriculum. Thus, the purpose of this study was to describe the inclusion of cupping therapy within accredited athletic training programs.A total of 56 athletic trainers who serve as therapeutic modalities educators participated in this study (age= 44 ± 9 years, certified experience = 21 ± 9 years, faculty experience = 14 ± 8 years). Participants were sent an electronic survey by email that assessed demographic information, inclusion of cupping therapy in coursework, and impressions on the necessity of cupping therapy in clinical practice. Measures of central tendency (means, standard deviations, frequencies) were calculated for all survey items. Data was downloaded and analyzed using a commercially available statistics package (SPSS Version 26, IBM, Armonk, NY). The majority of faculty members reported including cupping therapy in lecture-based education but did not include cupping therapy in lab-based education. Additionally, most participants reported not including cupping therapy on exams, quizzes, or research papers. Most faculty members did not believe that cupping therapy was a necessary skill for athletic training (57.1%, n = 32) or that cupping therapy warranted inclusion in athletic training accreditation standards (67.9%, n = 38). This finding appears to be in contrast with previous research on clinical athletic trainers, which indicated that athletic trainers felt cupping therapy was a necessary skill. Considering this apparent difference in opinion, athletic training educators should consider increasing the level of coverage cupping therapy receives within their curriculum. Further research should be conducted to determine the best method of knowledge transfer regarding cupping therapy.

Introduction

Cupping therapy is a therapeutic modality that has been used for over 5,000 years [1]. By using suction to decompress tissues, cupping therapy is employed by clinicians around the world for the purpose of improving blood flow, decreasing pain, increasing range of motion, and increasing function [2-4]. By the 2016 Olympics, cupping therapy has grown in popularity in the United States of America [1]. A large amount of this popularity is likely due to increased media interest resulting from elite level athletes receiving cupping therapy [5,6]. To date, there is still no consensus on the ideal parameters for prescribing and applying cupping therapy to either amateur or professional athletes [1]. This lack of consensus can be attributed in part to a lack of high quality studies and no agreed upon standardized methodology [4,7].

Studies have shown cupping therapy to produce a positive effect on local and regional blood flow [3,8,9]. When a cup is applied to the skin, the treated tissues undergo negative pressure that results in compression of the tissues in contact with the rim of the cup and decompression of the tissues in the cup. The lower pressure within the cup potentially causes a pressure differential between the skin within the cup and underlying superficial blood vessels [10]. When exposed to this change in pressure, blood vessels dilate, which causes localized increased blood flow at the site of treatment [10]. This increased blood flow may result in the decreased pain shown in previous research [11]. Cupping therapy may also reduce pain through other mechanisms. It has been reported that while the body is healing the marks left by cupping therapy, leukocytes are attracted to the area and the enzyme heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) is produced [11]. As the body breaks down HO-1, the bi products include heme, biliverdin, bilirubin, carbon monoxide, and iron [11]. During this process, the iron is sequestered by ferritin and the other bi products have direct and indirect effects that may create a better environment for healing at the treatment site [11].

In athletic training, cupping therapy has become more popular in recent years. Researchers have also begun investigating the uses for cupping therapy for treating athletic populations [1]. Recent studies have also shown that cupping therapy is used by the majority of clinical athletic trainers [12-14]. However, many of the athletic trainers surveyed in these studies reported not learning about cupping therapy in their athletic training curriculums. Thus, the purpose of this study was to describe the inclusion of cupping therapy within accredited athletic training programs.

Methods

Design

This study was conducted using a cross-sectional design utilizing an internet-based survey for data collection.

Participants

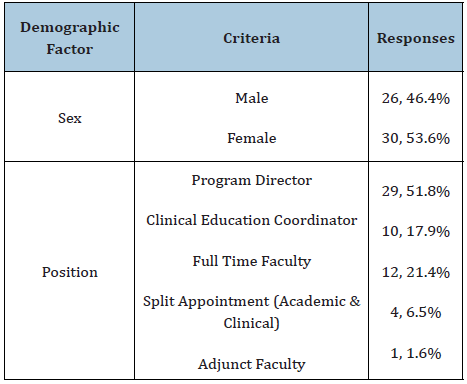

Table 1: Totals and percentage for participant demographic information.

Participants were recruited for this study by emailing the program directors for accredited athletic training programs that were listed as being in good standing with the Commission for the Accreditation of Athletic Training Education (CAATE). Program directors were asked to distribute an email containing an explanation of the study and a link to the survey to the faculty member who was primarily responsible for instructing athletic training students on therapeutic modalities. A total 56 athletic trainers who serve as therapeutic modalities educators participated in this study (age= 44 ± 9 years, certified experience = 21 ± 9 years, faculty experience = 14 ± 8 years). Demographic information regarding the participants is presented in Table 1. All participants were informed of the survey’s purpose at the beginning of the survey, at which point informed consent was obtained per the protocol approved by the University of Texas at Tyler Institutional Review Board.

Data collection

An email was sent to the program directors of CAATE accredited programs that were listed as “in good standing” on the CAATE website asking them to send the email invitation to the primary faculty member responsible for teaching therapeutic modalities. The message was then forwarded to all prospective participants inviting them to participate in an electronic survey via a hyperlink from a web-based server (Qualtrics Inc., Provo, UT) from in May 2020. The inviting message contained information about the investigators, the purpose of the study, the nature of the survey, and assurances that the participants could quit the survey at any time. A follow-up email was sent to program directors a week after the initial email and left open for a week prior to the survey being closed for statistical analysis.

Instrument

Following the informed consent and demographics section, the instrument contained items related to the inclusion of cupping therapy within course curriculum, beliefs on cupping therapy being a necessary skill for athletic trainers, and formal education and training regarding cupping therapy. Participants were also asked if they included cupping therapy in their graded course materials.

Ultimately, the survey consisted of 19 questions. These questions included: one question regarding informed consent, three multiple choice and three fill in the blank questions on demographics, one multiple choice question on the format of the participant’s modality course, five questions on the inclusion of cupping therapy in the participant’s modality course, two multiple questions on the participant’s beliefs about cupping therapy being a necessary skill in athletic training, and three questions on the participant’s education on cupping therapy.

Statistical analysis

Information from participant responses was downloaded and analyzed using a commercially available statistics package (SPSS Version 26, IBM, Armonk, NY). A total of 56 completed responses were included in the data analysis. Measures of central tendency (means, standard deviations, frequencies) were calculated where appropriate. Pearson correlations were calculated to assess the relationship between education on cupping therapy and beliefs that cupping therapy was a necessary skill. Significance was set at P < .05 a priori.

Results

Inclusion of cupping therapy in curriculum

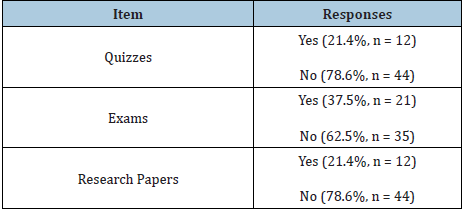

Participants reported that 58.9% (n = 33) covered cupping therapy within the lecture portion of their therapeutic modalities course. Conversely, only 48.2% (n = 27) reported covering cupping therapy during the laboratory portion of their therapeutic modalities course. Data on inclusion of cupping therapy in gradable materials is included in Table 2.

Table 2: Inclusion of cupping therapy in gradable materials.

Beliefs on cupping therapy

Over half of participants (57.1%, n = 32) agreed that they felt cupping therapy was not a necessary skill for athletic training practice. Conversely, 42.9% (n = 24) felt the cupping therapy was a necessary skill. The majority of participants also felt that cupping therapy should not be included in CAATE standards for education (67.9%, n = 38). In contrast, 32.1% (n = 18) felt that cupping therapy should be included in CAATE standards.

Correlation between cupping therapy education and beliefs

We identified a weak positive relationship between previous cupping therapy education in formal curriculum and the belief that cupping therapy was a necessary skill for athletic trainers (r = 0.362, P = .006). There was a very strong positive relationship between attendance of a cupping therapy presentation and the belief that cupping therapy was a necessary skill (r = 0.806, P < .001). We also identified a moderate positive relationship between holding a cupping therapy certification and believing that cupping therapy was a necessary skill (r = 0.505, P < .001). This suggested that individuals who had some form of education on cupping therapy were more likely to believe that cupping therapy is a necessary skill for athletic trainers.

We identified a moderate positive relationship between previous cupping therapy education in formal curriculum and the belief that cupping therapy should be included in CAATE standards (r = 0.455, P < .001). There was a strong positive relationship between attendance of a cupping therapy presentation and the belief that cupping therapy should be included in CAATE standards (r = 0.641, P < .001). We also identified a strong relationship between holding a cupping therapy certification and that cupping therapy should be included in CAATE standards (r = .636, P < .001). This suggest that individuals who had some form of education on cupping therapy were more likely to believe that cupping therapy should be included in CAATE standards.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to describe the inclusion of cupping therapy within therapeutic modalities courses taught in CAATE accredited athletic training programs. A secondary purpose was to describe the beliefs of athletic training educators toward cupping therapy.

Our findings indicate that over half of the participants felt that cupping therapy was not a necessary skill for athletic training clinical practice (57.1%, n = 32). Additionally, the majority of participants reported believing that cupping therapy should not be included in CAATE education standards (67.9%, n = 38). In fact, only 32.1% (n = 18) of athletic training educators surveyed reported feeling that cupping therapy should be included in CAATE education standards. These findings suggest that athletic training educators do not believe that cupping therapy is a necessary skill for clinically practicing athletic trainers.

While cupping therapy has grown increasingly popular in recent years, athletic trainers appear to be split with regard to their perceived knowledge of the modality [12-14]. Additionally, previous studies have reported a gap between perceived and actual knowledge of cupping therapy among athletic trainers [12-14]. This information suggests prospective athletic trainers might benefit from increased coverage of cupping therapy within athletic training programs. However, many athletic training educators reported not including cupping therapy in their laboratory portions of therapeutic modalities courses or gradable materials.

Previous research has indicated that clinical skills are subject to deterioration if they are not practiced over time [15,16]. One such study indicated that skills such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation can decrease in as little as six months [15]. On average, athletic trainers are more likely to use cupping therapy on a weekly basis compared to cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Still, if cupping therapy is not well covered during professional education, this skill may deteriorate faster than others. Additionally, there is a potential for knowledge and skill deterioration if the modality is not used regularly. In the absence of clinical practice, continuing education has been shown to be a valuable method of knowledge transfer and retention [16].

These findings may suggest a need to reconsider the inclusion information about the theory and concepts related to cupping therapy within athletic training curriculums. Athletic training educators should also consider including laboratory-based instruction on cupping therapy as well. Even if athletic training programs are able to include more information about cupping therapy, continuing education interventions should be considered for refreshing knowledge of the definition, modes of action, indications, and contraindications of cupping therapy. When these continuing education interventions are created, they should undergo evaluation and frequent re-evaluation to ensure that they are effective at improving and refreshing knowledge of cupping therapy.

A possible limitation of this study was the number of participants. However, this is a similar limitation that other survey based studies on athletic trainers have encountered, and may affect the generalizability of the results when looking to analyze across the profession [14-16]. This study demonstrates a differing opinion between athletic training educators and clinically practicing athletic trainers regarding the necessity of including cupping therapy in athletic training curriculums [12-14]. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to describe the inclusion of cupping therapy in athletic training curriculums. Future research should also be directed towards imparting and refreshing knowledge related to cupping therapy and other therapeutic modalities.

Conclusion

In conclusion, cupping therapy is an increasingly popular modality being used by athletic trainers and is viewed by many clinicians as a necessary skill. However, the athletic training educators surveyed in this study appeared to believe that cupping therapy was not a necessary skill. Even though previous studies have suggested the majority of athletic trainers use cupping therapy to some extent in their clinical practice, many educators reported not including laboratory-based instruction on the skill. Given the growing popularity of cupping therapy, athletic training educators should consider including more content on cupping therapy within their therapeutic modalities curriculums.

References

- Bridgett R, Mas D, Prac C, Klose P, Duffield R, et al. (2018) Effects of cupping therapy in amateur and professional athletes: Systematic review of randomized controlled trials. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 24(3): 208-219.

- Cage SA, Warner BJ, Gallegos DM, Sims-Koenig K (2020) Effects of cupping therapy on Lower Quarter Y-Balance Test scores in collegiate baseball players. Research & Investigation in Sports Medicine 6(1): 466-468.

- Arce-Esquivel A, Warner B, Gallegos D, Cage SA (2017) Effect of dry cupping therapy on vascular function among young individuals. International Journal of Health Sciences 5(3): 10-15.

- Cao H, Lia X, Yan X, Wang N, Bensoussan A, et al. (2014) Cupping therapy for acute and chronic pain management: A systematic review. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medical Sciences 2: 49-61.

- Futterman M (2016) Michael phelps leads rio cupping craze. The Wall Street Journal.

- Lyons K (2016) Interest in cupping therapy spikes after Michael Phelps gold win. The Guardian.

- Cao H, Li X, Liu J (2012) An updated review of the efficacy of cupping therapy. PLos ONE 7(2): e31793.

- Cage SA, Warner BJ, Gallegos DM (2020) Effect of cupping therapy on skin surface temperature in healthy individuals. Journal of Sports Medicine and Allied Health Sciences 5(3).

- Chi L, Lin L, Chen C, Wang S, Lai H, et al. (2016) The effectiveness of cupping therapy on relieving chronic neck and shoulder pain: A randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2016: 7358918.

- Liu W, Piao S, Meng X, Wei L (2013) Effects of cupping on blood flow under the skin of back in healthy human. World Journal of Acupuncture-Moxibustion 23(3): 50-52.

- Lowe D (2017) Cupping therapy: An analysis of the effects of suction on the skin and possible influence on human health. Complimentary Therapies in Clinical Practice 29(2017): 162-168.

- Cage SA, Warner BJ, Gallegos DM, Winkelmann ZK (2020) Athletic trainers’ perceived and actual knowledge of cupping therapy concepts. Journal of Sports Medicine and Allied Health Sciences 5(3).

- Cage SA, Winkelmann ZK, Warner BJ, Gallegos DM (2020) Perceived and actual knowledge of cupping therapy concepts among athletic training preceptors in CAATE accredited programs. Research & Investigations in Sports Medicine 6(3): 514-518.

- Cage SA, Warner BJ, Gallegos DM, Goza JP, Winkelmann ZK (2020) Perceived and Actual knowledge of cupping therapy concepts among athletic trainers in the state of Texas. Research & Investigations in Sports Medicine 6(4): 538-542.

- Yang CW, Yen ZS, McGowan JE, Chen HC, Chiang WC, et al (2012) A systematic review of retention of adult advanced life support knowledge and skills in healthcare providers. Resuscitation 83(9): 1055-1060.

- Schellhase K, Plant J, Rothschild C (2015) Collegiate athletic trainers perceived and actual knowledge of therapeutic ultrasound concepts. International Journal of Athletic Therapy and Training 20(5): 43-53.

© 2020 S Andrew C. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)