- Submissions

Full Text

Research & Investigations in Sports Medicine

Sports Ethnography and Anthropology: Issues and Scopes-A Preliminary Overview

Abhijit Das*

Department of Anthropology, West Bengal State University, India

*Corresponding author: Abhijit Das, Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology,West Bengal State University, West Bengal, India

Submission: April 16, 2018;Published: July 05, 2018

ISSN: 2577-1914 Volume3 Issue4

Preamble

Ethnography is the study of people in naturally occurring settings or ‘fields’ by methods of data collection which capture their social meanings and ordinary activities, involving the researcher participating directly in the setting, if not also the activities, in order to collect data in a systematic manner but without meaning being imposed on them externally [1]. The goal of ethnography is ‘to communicate understandings about a culture which are held by members of the cultures themselves’ [2], Anthropology distinguishes itself from the other social sciences through the great emphasis placed on ethnographic fieldwork as the most important source of new knowledge about society and culture [3].

Defined in this way, it is one of the principal research methods in the social sciences (especially in Anthropology), and foremost in the repertoire of qualitative researchers. It is not one particular method of data collection but a style of research that is distinguished by its objectives, which are to understand the social and cultural meanings and activities of people in a given ‘field’ or setting, and its approach, which involves close association with, and often participation in this setting. As such, ethnography has a distinguished career in the social sciences, including social -cultural anthropology.

Origin and Historical Genesis -A Brief Outline

Ethnography is qualitative research method which is originated in the field of Anthropology, where it was used to study cultures seen as, exotic, or unfamiliar in ‘the West’. The term ‘Ethnography’ is used to describe both the research style and the written product of that research activity [4]. The Chicago School of urban sociologists, who were prominent from the 1940s to 1960s and were committed to symbolic interactionism, has also had a seminal influence on the development of the ‘genre’ of sociological ethnography [4]. They helped to fix its focus on the micro community, subculture, or subworld.

The aim of ethnography

The aim of ethnography is to comprehend the totality of the culture, group, social world or subculture being studied and hence it is finally considered as a mainstay of anthropological fieldwork as well as research. It endeavours to understand how people behave in their contexts as well as ‘natural settings’, and to construct the participants’ perspective(‘emic’) and make explicit their taken for granted assumptions [5]. Ethnographic studies involve in-depth and extended study. Although Participant Observation has been ‘taken as the type-case of ethnographic procedures, [4], within ethnographic investigation a number of research techniques are employed including document analysis, participant observation, and in-depth interviews. It is worth mentioning that participant observation is the mainstay of anthropological ethnography [6-12].

Sports Ethnography and Anthropological Issues: A Brief Overview

In its simplest sense of the term, Sports Ethnography is nothing but the first hand study of sports as an aspect of society and culture or as a form of subculture. Over the past few decades ethnographic research has become popular in many fields of study, including sports studies. The Sociology of Sports Journal (special issue, 1997) was consisted of some excellent summaries of various sporting ethnographies. However, it is important to recognize that the meaning and practice of ethnography, in sport as in other fields, varies considerably. As Silk [13] argued, a variety of different ‘approaches, schools, or sub-types exist’ under the ‘banner’ of ethnography and these are underpinned by different and often opposing theoretical, philosophical, epistemological and ontological assumptions. Thus, the genealogy of contemporary ethnography needs to be understood as a ‘constant process of oppositions’ [13].

If we look back to the early work in sports (during the 1970s) in the symbolic interactionist tradition focused on cultural description, reflecting early anthropological work. But writers as well as ethnographers in this tradition did not place their findings in their broader social and historical contexts [14], nor did they explore the wider power relationships involved. In the 1980s and 1990s, sports sociologists adopted more contextualized ethnographic approaches to study different life worlds, subcultures, and identity practices and these ranged from football fans to golf, from climbing to skateboarding [15]; such a contextualizing approach attempts not just to understand cultural experience in its face to face production and location in time, it also wants to situate that interaction in the so- cial reproduction of relations of sports and society as a whole (Hollands, 1985:17). In this context, Beals [15] gives a detailed review of the ways in which symbolic interactionism and cultural studies have been combined in critical ethnography.

Recent sub-cultural studies of sports, have integrated a critical cultural studies perspective with the rigorous documentation of interactions which generate symbolic meanings and identity [16]. Ethnographic work on deviance has been another productive line in sports research, generating numerous studies of the performance of masculinity in football fan cultures [17] as well as boxing (Sugden, 1996) and criminality among ticket scalpers [18] and sports media, addressing, for example, their institutionalized practices, the gendered nature of production and the consumption of sports media by audience.

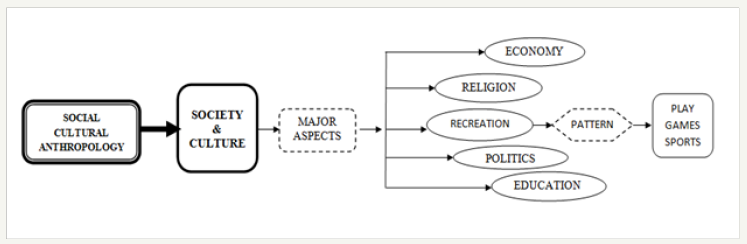

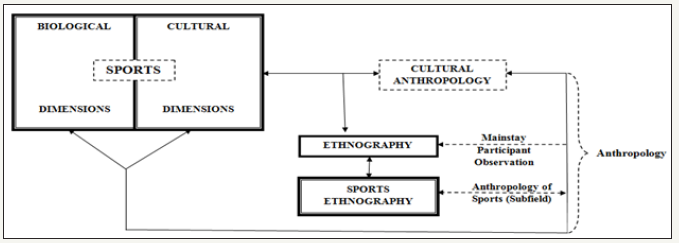

It is worth mentioning at the end that the typical sports ethnography is still absent in Indian contexts, except the work of the present author in his Ph.D Thesis on Social-Cultural Study of Games in West Bengal, India (2002). Some stray anthropological observations on tribal sports [19] along with the contemporary rural and urban based modern sports and allied institutions have been explored by very few sociologists, historians, anthropologists, and folklorists. In this context, some Bengali novels as written by sports journalists cum authors (e.g. Mati Nandi, Rupak Saha) are mentionable, namely, Koni (the story of a swimmer’s achievement), Stopper, Striker(auto ethnographic novels of soccer players of Bengali Hindu lower middle class families). These novels are the typical examples of interface between literary ethnography and sports ethnography [20-22] (Figure 1 & 2).

Figure 1: Sports in social-cultural anthropology.

Figure 2: Sports-ethnography-anthropology: interrelationship.

Therefore, in using ethnographic techniques, the sports ethnographers as well as social-cultural anthropologists are attempting to capture the meanings used and made by members of the culture to describe its sporting and physical activity as an important recreational aspect or pattern, like music and dance. Interviews involve the direct questioning of members of the culture being studied in order to hear about their sports and allied activities from an insider’s (‘emic’) perspective. As a means of complementing this approach and the information gleaned, ethnographers often employ participant observation (as in Anthropology) techniques, whereby they participate in on-going sports events of the culture as well as observe what is going on around sports events in a holistic perspective. As such, they adopt an outsider’s (‘etic’) perspective and orientation. In either case, they are searching for the meanings and functions of a culture’s sporting behavior and allied arenas in an integrated whole.

References

- Brewer JD (2010) Ethnography. Rawat Publications, New Delhi, India.

- Harris J, Park R (1983) Play, games, and sports in cultural contexts. Champaign, Human Kinetics, USA.

- Eriksen TH (2010) Small places, large issues: an introduction to social and cultural anthropology. Pluto Press, London, UK.

- Atkinson P (1990) The ethnographic imagination: textual construction of reality. Routledge, UK.

- Hammersley M, Atkinson P (1995) Ethnography: principles in practice. Routledge, London, UK.

- Ember CR, Ember M, Peregrine PN (2007) Anthropology. Pearson, New Delhi, India.

- Scupin R,DeCorse CR (2005) Anthropology: A global perspective. Prentice Hall of India PVT LTD, New Delhi, India.

- Miller B (2011) Cultural anthropology. PHI Learning, New Delhi, India.

- Eller JD (2009) Cultural anthropology: global forces, local lives. Routledge, New York, USA.

- Kottak CP (2000) Cultural anthropology. McGraw Hill, USA.

- Haviland WA (2002) Cultural anthropology. Wadsworth Thompson Learning, USA.

- Nanda S, Warms RL (2011) Cultural anthropology. Wadsworth Cengage Learning, USA.

- Silk ML (2005) Sporting etnography: Philosophy, methodology, and reflection. In: Andrews DL, Mason DS, Silk M (Eds.),Qualitative methods in sports studies. Berg, Oxford, USA, pp. 65-103.

- Donnelly P (1985) Sport Subcultures.Exercise and Sport Sciences Review 13:539-578.

- Beals B (2002) Symbolic interactionism and cultural studies: doing critical ethnography. In: Maguire J, Young K (Eds.),Theory, Sport and Society. Oxford, USA.

- Crosset T, Beal B (1997) The use of subculture” and “subworld” in ethnographic works on sport: a discussion of definitional distinctions. Sociology of Sport Journal 14: 73-85.

- Giulianotti R (1995) Participant observation and research into football hooliganism: reflections on the problems of entrée and everyday risks. Sociology of Sport Journal 12:1-20.

- Atkinson M (2000) Brother, can you spare a seat? Developing recipes of knowledge in the ticket scalping subculture. Sociology of Sports Journal 17: 151-170.

- Narayan S (1995) Play and games in tribal india. Commonwealth Publishers, New Delhi, India.

- Armstrong G, Giulianotti R (1997) Entering the field: new perspectives on world football. Oxford, Berg, UK.

- Donnelly P (2000) Interactionism. In: Coakley J, Dunning E (Eds.), Handbook of Sport Studies. Sage, London, UK.

- Sands R (2002) Sporting ethnography. Champaign, Human Kinetics, USA.

© 2018 Abhijit Das. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)