- Submissions

Full Text

Research & Investigations in Sports Medicine

The Effects of Peppermint Oil Ingestion on the Ventilatory Threshold: A Pilot Study

David F Salas and Chi-An W Emhoff*

Department of Kinesiology, Saint Mary’s College of California, USA

*Corresponding author: Chi-An WEmhoff, Department of Kinesiology, Saint Mary’s College of California, Moraga, CA, USA

Submission: December16, 2017;Published: July 05, 2018

ISSN: 2577-1914 Volume3 Issue3

Abstract

Peppermint oil (menthapiperita), a commonly used herbal remedy for gastrointestinal distress because of its effect of reduced smooth muscle tonicity, has been shown to improve results on pulmonary function tests, possibly due to bronchodilatory mechanisms. Given the potential benefits of peppermint on pulmonary function, our pilot study aimed to investigate the acute effects of peppermint oil ingestion on exercise performance, in particular the ventilatory threshold. Characterized as the inflection point at which pulmonary ventilation increases out of proportion to metabolic rate, the ventilatory threshold is positively associated with endurance performance. We hypothesized that a single ingestion of 1mL peppermint oil diluted in 250mL water would raise the ventilatory threshold as a percentage of maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max) during a cycling graded exercise test 10 minutes following ingestion. Six healthy male participants performed two graded maximal exercise tests on a cycle ergometer under randomized, single blind trials of peppermint oil and placebo. For each exercise test, agreement amongst three analytical methods was used to validate the inflection point at which the ventilatory threshold occurred. We found that ingestion of peppermint oil resulted in the ventilatory threshold occurring at a significantly higher percentage of VO2max compared to placebo (70.2±2.2% of VO2maxvs66.2±2.0% of VO2max, p<.05). In contrast, VO2max values were not different between the two conditions. Our findings suggest that peppermint oil ingestion may acutely have a positive impact on the ventilatory threshold by raising the percentage of VO2max at which the ventilatory threshold occurs. Further research is needed to elucidate the mechanism through which peppermint oil elicits this response.

Keywords: Peppermint oil;Ventilatory threshold;Endurance exercise

Abbreviations: VO2max: Maximal oxygen consumption; VO2: Oxygen consumption; VCO2: CarbonDProduction; W: Watts; PER: Respiratory Exchange Ratio; VE: Ventilation

Introduction

Peppermint is a hybrid herb of spearmint and water mint that possesses a wide range of remedial benefits, including pain management, anti-inflammation, and antibacterial and antiviral properties [1-3]. Peppermint essence, commonly denominated peppermint oil (mentha piperita), is included in clinical practice guidelines to ingest a recommended daily dose of 15-30 drops to treat gastrointestinal distress such as irritable bowel syndrome [4]. The purported mechanism of peppermint oil is a dose-dependent antagonistic response in calcium channels across the smooth muscle cell membrane, leading to relaxation and antispasmodic effects within the gastrointestinal tract [1,3]. Additionally, previous studies have found that peppermint oil ingestion improves performance on pulmonary function tests in healthy individuals, including forced vital capacity, peak inspiratory flow rate, and peak expiratory flow rate [5], possibly due to bronchodilatory mechanisms from reduced smooth muscle tonicity. However, these positive effects on pulmonary function were not observed in patients with chronic mild asthma [6].

Given the gastrointestinal and pulmonary applications for peppermint in healthy individuals, researchers have shown interest in investigating the ergogenic potential of peppermint during exercise. Sӧnmez et al. [7] found that following oral supplementation of peppermint oil, blood lactate levels were significantly lower after a 400-meter dash. Another study conducted by Riera et al. [8] found that following the supplementation of 0.5% menthol beverages, there was a significant improvement in 20kilometer time trials in trained cyclists. Peppermint oil was also shown to improve performances in isometric grip force, vertical and long jumps, and visual and audio reaction times in healthy individuals five minutes and one hour following oral administration [2]. The exact mechanisms related to these ergogenic effects of peppermint oilduring exercise are unknown, although it is hypothesized to involve stimulating the reticular activatingsystem, which is responsible for alertness within the central nervous system [2,9].

While peppermint oil has been shown to improve pulmonary function tests at rest [5] and may have ergogenic effects during exercise [2,5,7-9], studies investigating the acute effects of peppermint on the ventilatory threshold during a cycling graded exercise test to exhaustion to our knowledge have not been done. Ventilatory threshold is characterized as the point at which ventilation increases out of proportion to metabolic rate at exercise intensities beyond 50% to 60% of maximal oxygen consumption (VO2max) [10-13]. Quantified as a percentage of VO2max, the ventilatory threshold improves with endurance training and has been shown to predict maximal endurance performance [14-16], subject to the lungs’ capacity to eliminate carbon dioxide during exercise [17]. Hence, the purpose of this pilot study was to examine the acute effects of peppermint oil ingestion on the ventilatory threshold during a graded maximal exercise test in healthy individuals. Due to the previously reported ergogenic effects of peppermint oil administered five to 10 minutes before exercise [2,5,7-9], We hypothesized that oral ingestion of peppermint oil 10 minutes prior to a graded exercise test would increase the percentage of VO2max at which the ventilatory threshold occurred with no change in VO2max values.

Materials and Methods

Participants

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Saint Mary’s College and conformed to the standards set by the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation in the study. Six healthy male volunteers (20.5±2.2 age; 71.0±8.1kg bodyweight; 179.8±4.4cm height) (Table 1) were recruited from Saint Mary’s College of California via posted notices and word of mouth. Participants completed a medical history questionnaire and were included in the study if they were non-asthmatic, nonsmokers, free of medications, and have no indications of being allergic to any forms of mint.

Table 1: Subject characteristics. Values are means ±SD

Protocol

Participants were familiarized with the laboratory setting and the measurement techniques prior to data collection. Using a singleblind study design, participants performed a graded exercise test on an electronically braked leg-cycle ergometer (Lode Excalibur Sport, Netherlands) on two occasions separated by one week. The order of peppermint or placebo conditions was randomized. Participants were instructed to fast for two hours prior to exercise testing and to refrain from caffeine and strenuous exercise for 12 hours prior to examination. The exercise test was conducted 10 minutes following oral ingestion of a peppermint oil solution (1mL peppermint oil in 250mL of water) or placebo (250mL of decaffeinated tea) to allow time for absorption of the drink. The selected dose was based on the manufacturers recommended serving size (Peppermint Leaf Extract Alcohol Free, Nature’s Answer), as well as the clinical practice guidelines for peppermint oil ingestion [4]. Decaffeinated tea was used as the placebo because of its similarity in appearance and taste to the peppermint oil solution. Participants did not appear to be able to identify the peppermint versus the placebo drink.

To determine VO2max, exercise power output started at 60W for a 3minute warm-up and was increased by 30 W every minute until volitional fatigue. Subjects were instructed to maintain a consistent cycling cadence of ~80RPM throughout the test. Expired respiratory gases were monitored continuously throughout the test via an open-circuit, automated, indirect calorimetry system (TrueOne metabolic system; ParvoMedics, Sandy, UT) that was calibrated using room air and a certified calibration gas. Continuous data for oxygen consumption (VO2sub>), carbon dioxide production (VCO2sub>), pulmonary ventilation (VE), respiratory exchange ratio (RER), and heart rate via a chest strap monitor (Polar Electro Inc., New York) were averaged every 15 seconds. Several quantifiable criteria were used to determine whether or not VO2max was achieved.

These criteria included: a plateau in VO2 despite an increase in workload (less than 150mL O2 increase over the final minute of exercise), heart rate within 10 beats of age-predicted maximum, and a respiratory exchange ratio (RER) of 1.10 or greater. Ventilatory threshold was determined using agreement amongst three analytical methods [12,13,15]. First, the ventilatory threshold was determined as the point at which VE increases nonlinearly with time (VE vs. time). Second, the ventilatory threshold was determined as the point at which VCO2 increases disproportionally relative to VO2 (VCO2 vs. VO2). Third, the ventilatory threshold was determined as the point at which VE increases disproportionally relative to VO2 (VE/VO2 vs. time). Due to the subtle inflection at which the ventilatory threshold occurs, we applied these three analytical methods to enhance reliability of our determination of the exercise ventilatory threshold.

Statistical analysis

Differences between peppermint and placebo conditions were analyzed using a paired student’s t-test (Microsoft Excel). Statistical significance was set at α<.05. Values are presented as means±SE unless otherwise noted.

Results

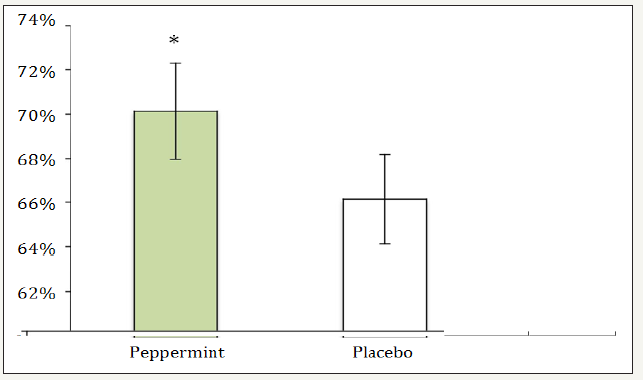

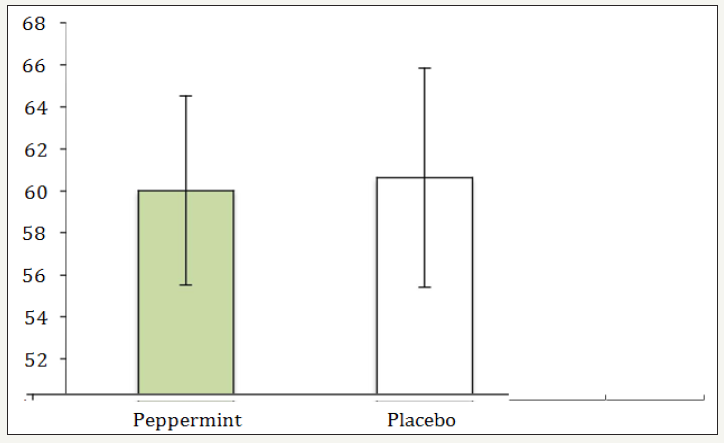

The ventilatory threshold andVO2maxwere determined for each exercise test. The three analytical methods are shown for one participant as an example (Figure 1), demonstrating agreement on a mutual point for determining the exercise ventilatory threshold. We observed that following oral ingestion of peppermint oil, the ventilatory threshold occurred at a higher percentage of VO2max compared to placebo (70.2±2.2% of VO2max vs. 66.2±2.0% of VO2max, p<.05, Figure 2). The VO2max values were not different between the peppermint and placebo conditions (60.0±4.5ml/kg/min vs. 60.6±5.2ml/kg/min, Figure 3).

Figure 1: Three methods were used to determine the ventilatory threshold: a) the point at which VEincreasesnonlinearly with time, b) the point at which VCO2increases disproportionally relative to VO2, and c) the point at which VE increases disproportionally relative to VO2. In this example, all methods agree on a ventilatory threshold occurring at 16.8 minutes at a VO2 of 3.7L/min, corresponding to 78% of VO2max.

Figure 2: The ventilatory threshold occurred at a higher percentage of VO2maxfollowing peppermint oilingestion, compared to placebo. *Significantly different from placebo condition (p<.05).

Figure 3: VO2max values were not different between the peppermint and placebo conditions.

Discussion

The aim of this pilot study was to examine the acute effects of peppermint oil ingestion on the ventilatory threshold during a cycling graded maximal exercise test. Our findings support our hypothesis that oral ingestion of 1mL of peppermint oil in 250mL of water may increase the ventilatory threshold of healthy participants as a percentage of VO2max, without affecting VO2max values. These results complement past research by dwelling deeper into the ergogenic effects of peppermint on exercise parameters such as the ventilatory threshold.The control of breathing during exercise is fascinating and complex. The increase in ventilation, or hyperpnea, observed during exercise is thought to be driven by feedforward input from central command as well as feedback pathways from central and peripheral chemoreceptors and muscle afferent mechanoreceptors [11,17]. At high exercise intensities, ventilation increases out of proportion to workload, which is observed as a hyperventilatory response, marking the exercise ventilatory threshold [12,15]. The primary mechanisms behind the ventilatory threshold are related to metabolic acidosis stimulating central chemoreceptors and arterial hypoxemia stimulating peripheral chemoreceptors, although these exact underlying mechanisms are still a source of controversy [11,18-20].

Since past research has shown enhancing effects of peppermint oil ingestion on forced vital capacity, peak inspiratory flow rate, and peak expiratory flow rate [5], it is plausible that during exercise, peppermint may augment bronchodilation to improve pulmonary gas exchange, particularly carbon dioxide elimination. The mechanism driving this proposed bronchodilation may stem from reduced smooth muscle tonicity due to peppermint [1,3], although this has not yet been directly shown in the human pulmonary system. In vitro studies in rodents have reported the antispasmodic effects of peppermint oil on the trachea by reducing the amplitude of smooth muscle contractions during electric stimulation [3]. Therefore, if the peppermint-induced bronchodilatory response facilitates carbon dioxide elimination during exercise to allow the ventilatory threshold to occur at higher exercise intensity [17], then there may be reason to suggest that peppermint supplementation could serve as an ergogenic aid to endurance athletes. However, since we found no acute effect of peppermint oil ingestion on VO2max results, it is uncertain whether the change in ventilatory threshold would translate into improved endurance performance. This finding was consistent with a previous study on peppermint inhalation, which observed no significant effect on VO2max results in male athletes undergoing a treadmill Bruce protocol test [21].

Other researchers found that the inhalation of mint essential oils improved 1500 meter time trial performance in young men [22], consistent with our findings that the effects of peppermint may be beneficial for pulmonary ventilation during endurance exercise. Additionally, long-term supplementation of peppermint oil for 10 days resulted in increased ventilation during a treadmill Bruce protocol test, including an increase in chest circumference at maximal inhalation, suggesting a reduction in bronchial smooth muscle tonicity [5]. Further studies investigating peppermint oil supplementation prior to continuous endurance exercise would be needed to explain the mechanisms for these observations.

Previous research has reported that peppermint ingestion and aroma inhalation may have widespread effects on the central nervous system [2,9,23-25]. Effects may include decreased reaction times to visual and audio stimulants [2], elevated mood and alertness [9,25], and increased electroencephalography activity [23,24]. Peppermint also contains a chemical compound, menthol, which has been shown to stimulate cold thermoreceptors [26], resulting in autonomic heat-gain responses such as shivering and skin vasoconstriction [27]. These effects on the central nervous system may alter feed-forward input from central command to control ventilation [11,28], possibly contributing to the observed increased in exercise ventilatory threshold in this study.

Limitations

While we found good agreement amongst the three analytical methods to determine ventilatory threshold in our participants, the small sample size in our pilot study is a limitation, impacting our confidence in drawing broader conclusions about significant effects of peppermint oil on the ventilatory threshold. Also, our participants were all male college students, so while the results were encouraging, they may not be generalizable. Finally, additional blood data collection pertaining to purported mechanisms of the ventilatory threshold, such as lactate, pH and oxygen saturation, would have strengthened the study.

Conclusion

In summary, we found that 10 minutes following oral ingestion of 1mL of peppermint oil in 250mL of water, the ventilatory threshold occurred at a higher percentage of VO2max during a cycling graded exercise test, compared to placebo. However, VO2max was not acutely affected by peppermint oil ingestion. We conclude that peppermint oil may have ergogenic properties during aerobic exercise at intensities near the ventilatory threshold. However, further studies involving a larger sample are warranted to understand the mechanisms of peppermint oil supplementation during exercise.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to the participation of enthusiastic students in this project.This research was supported by the Saint Mary’s College Faculty Development Fund and Student Development Award.

References

- Kligler B, Chaudhary S (2007) Peppermint Oil. Am Fam Physician 75(7): 1027-1030.

- Meamarbashi A (2014) Instant effects of peppermint essential oil on the physiological parameters and exercise performance. Avicenna J Phytomed 4(1): 72-78.

- Sachan AK, Das DR, Shuaib MD, Gangwar SS, Sharma R (2013) An overview on menthae piperitae (peppermint oil). Int J of Pharma Chem Biol Sci 3(3): 834-838.

- Mearin F, Ciriza C, Mínguez M, Rey E, Mascort JJ, et al. (2016) Clinical Practice Guideline: Irritable bowel syndrome with constipation and functional constipation in the adult. Rev EspEnferm Dig 108(6): 332- 363.

- Meamarbashi A, Rajabi A (2013) The effects of peppermint on exercise performance. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 10(15): 1-6.

- Tamaoki J, Chiyotani A, Sakai A, Takemura H, Konno K (1995) Effect of menthol vapour on airway hyperresponsiveness in patients with mild asthma. Respir Med 89(7): 503-504.

- Sӧnmez GT, Colak M, Sӧnmez S, Schoenfeld B (2010) Effects of oral supplementation of mint extract on muscle pain and blood lactate. Biomed Hum Kinetics 2(1): 66-69.

- Riera F, Trong TT, Sinnapah S, Hue O (2014) Physical and perceptual cooling with beverages to increase cycle performance in a tropical climate. PLoS One 9(8): 1-7.

- Raudenbush B, Corley N, Eppich W (2001) Enhancing athletic performance through the administration of peppermint odor. J Sport Ex Psych 23: 156-160.

- Blain G, Meste O, Bouchard T, Bermon S (2005) Assessment of ventilatory thresholds during graded and maximal exercise test using time varying analysis of respiratory sinus arrhythmia. Br J Sports Med 39(7): 448- 452.

- Forster HV, Haouzi P, Dempsey JA (2012) Control of breathing during exercise. ComprPhysiol 2(1): 743-777.

- Neder JA, Stein R (2006) A simplified strategy for the estimation of the exercise ventilatory thresholds. Med Sci Sports Exerc 38(5): 1007-1013.

- Weston SB, Gray AB, Schneider DA, Gass GC (2002) Effect of ramp slope on ventilation thresholds and VO2 peak in male cyclists. Int J Sports Med 23(1): 22-27.

- Plato PA, McNulty M, Crunk SM, Tug Ergun A (2008) Predicting lactate threshold using ventilatory threshold. Int J Sports Med 29(9): 732-737.

- Reybrouck T, Ghesquiere J, Weymans M, Amery A (1986) Ventilatory threshold measurement to evaluate maximal endurance performance. Int J Sports Med 7(1): 26-29.

- Vago P, Mercier J, Ramonatxo M, Prefaut C (1987) Is ventilatory anaerobic threshold a good index of endurance capacity? Int J Sports Med 8(3): 190-195.

- Scheuermann BW, Kowalchuk JM, Paterson DH, Cunningham DA (1999) VCO2 and VE kinetics during moderate- and heavy-intensity exercise after acetazolamide administration. J Appl Physiol 86(5): 1534-1543.

- Brooks GA (2000) Intra- and extra-cellular lactate shuttles. Med Sci Sports Exerc 32(4): 790-799.

- Meyer T, Faude O, Scharhag J, Urhausen A, Kindermann W (2004) Is lactic acidosis a cause of exercise-induced hyperventilation at the respiratory compensation point? Br J Sports Med 38(5): 622-625.

- Scheuermann BW, Kowalchuk JM, Paterson DH, Cunningham DA (2000) Carbonic anhydrase inhibition delays plasma lactate appearance with no effect on ventilatory threshold. J Appl Physiol 88(2): 713-721.

- Esfangreh AS, Azarbaijani MA, Habibi B (2011) Effects of mentha piperita inhalation on some factors of physical and movement performance of male athlete students. Phys Ed Sport 11(1): 40-42.

- Jaradat NA, Zabadi HA, Rahhal B, Hussein AM, Mahmoud JS, et al. (2016) The effect of inhalation of Citrus sinensis flowers and Mentha spicata leave essential oils on lung function and exercise performance: aquasiexperimental uncontrolled before-and-after study. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 13(36): 1-8.

- Kobal G, Hummel C (1989) Cerebral chemosensory evoked potentials elicited by chemical stimulation of the human olfactory and respiratory nasal mucosa. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 71(4): 241-250.

- Lorig TS, Huffman E, DeMartino A, DeMarco J (1991) The effects of low concentration odors on EEG activity and behaviour. J Psychophysiol 5(1):69-77.

- Varney E, Buckle J (2013) Effect of inhaled essential oils on mental exhaustion and moderate burnout: A small pilot study. J Altern Comp Med 19(1): 69-71.

- Schäfer K, Braun HA, Isenberg C (1986) Effect of menthol on cold receptor activity: Analysis of receptor processes. J Gen Physiol 88(6): 757-776.

- Tajino K, Matsumura K, Kosada K, Shibakusa T, Inoue K, et al. (2007) Application of menthol to the skin of whole trunk in mice induces autonomic and behavioral heat-gain responses. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 293(5): 2128-2135.

- White MD, Cabanac M (1996) Exercise hyperpnea and hyperthermia in humans. J Appl Physiol 81(3): 1249-1254.

© 2018 Chi-An WEmhoff. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)