- Submissions

Full Text

Research & Investigations in Sports Medicine

Copper Compression Wear: No Better Than the Sum of its Parts

Amanda Peach1 and Anthony Mortara2*

1Hutchins Library, Berea College, USA

2Health and Human Performance, Berea College, USA

*Corresponding author: Anthony Mortara, Berea College, CPO 2187, Berea, KY, United States

Submission: August 16, 2017; Published: September 25, 2017

ISSN: 2577-1914 Volume1 Issue1

Abstract

Copper compression clothing is a seemingly unstoppable fitness trend, despite several articles in popular literature debunking their claims of enhanced performance, reduced recovery time, and even pain management. Despite copper compression wear companies’ claims of science-proven effectiveness, search for scholarly literature on compression clothing left the authors empty-handed. The authors reviewed the current literature on both copper and compression wears separately and arrived at the conclusion that the absence of research in this field appears justified.

Keywords: Copper compression; Pain management; Recovery; Performance

Opinion

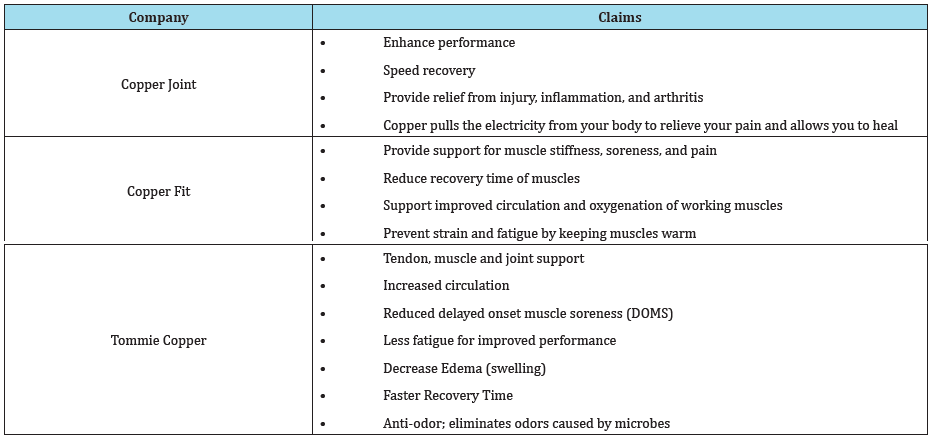

In 2015, fitness clothing company Tommie Copper was sued by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) for false claims regarding their copper compression wear. According to the FTC’s Bureau of Consumer Protection, Tommie Copper deceived consumers by claiming that the pain relief provided by their copper compression wear was so effective that it represented a legitimate alternative to medicinal or surgical interventions [1]; ultimately, the company agreed to pay 1.35 million in fines to settle the suit. That same year, articles appeared in popular magazines Time and Consumer Reports debunking the claims surrounding copper compression gear. Even when faced with such high profile criticism, sales of copper compression sportswear persisted. Besides Tommie Copper, other copper compression brands such as Copper Fit, Copper Compression, and Copper Joint benefited from this trend, as did their celebrity spokes people, like retired NFL champion, Brett Favre. What is copper compression clothing and how does it differ from traditional compression wear? While there does exist a history of medical-grade compression wear designed to improve circulation and lymphatic system functioning, that is not of interest here; the focus of this article is on commercial copperinfused compression wear which is readily available to consumers, over-the-counter. Copper compression performance clothing is not limited to compression sleeves or stockings; companies have expanded their arsenal to include shorts, shirts, socks, and even underwear made of form-fitting elastic material which is infused with copper fibers. These compression garments are designed to deliver graduated pressure, in addition to other benefits, as articulated in the Table 1. The chart is a list of claims made by the specific companies mentioned earlier, regarding the benefits of their copper compression wear. These assertions regarding the benefits of their brands come directly from their websites, as of July 2017, and are recorded here verbatim.

Table 1: Purported benefits by specific copper compression companies.

So, does the research support these claims? Currently, there exists a gap in the scholarly analysis of copper compression clothing specifically. If the treatment of the subject by the popular press and advocacy groups, such as Truth in Advertising, is to be believed, this dearth exists because the benefits of copper compression have been overstated for marketing purposes. There have been a significant number of studies which investigated the benefits of compression wear in general, with a focus on performance and recovery, but none on copper-infused compression wear. Additionally, there have been studies which have determined that copper, and copper textiles, can be highly effective at preventing the growth of bacteria. Finally, there have been several studies which have investigated copper, in the form of a bracelet, as a treatment for pain in patients suffering from arthritis. However, to date, none of the professional literature has investigated copper and compression simultaneously.

Discussion

Research on analgesic properties of copper

The FTC suit against Tommie Copper alleged that the company’s claims to provide pain relief were unsubstantiated. Since then, the company has pulled pain relief language from their ads. Copper Fit and Copper Joint continue to make such claims, however, and Copper Joint goes so far as to claim that the copper in their clothing “pulls the electricity from your body to relieve your pain and allows you to heal.” Unfortunately, the science does not support these claims. A 2009 study of magnetic and copper bracelets as a treatment for Osteoarthritis patients found that copper was ineffective at managing pain, stiffness, and physical function [2]. Any analgesic benefits associated with the copper bracelets were psychological in nature and were the result of the placebo effect. A 2013 study of the use of copper bracelets and magnetic wrist straps among Rheumatoid Arthritis patients reached a similar conclusion: that these items had no statistically significant therapeutic effects upon the patient group, offering no reduction in pain, inflammation, disability or medication use beyond the placebo affect [3]. Copper Fit and Copper Joint might do well to follow Tommie Copper’s lead and remove such dubious claims from their marketing materials.

Research on antimicrobial properties of copper

Can copper-impregnated fibers help fight odors, as Tommie Copper claims? On their website, the company cites a 2011 review by Grass & Soliozwhich [4] confirmed the antimicrobial qualities of copper, discussing its power to kill bacteria, yeast and viruses through a process known as “contact killing”; when microorganisms come into contact with copper surfaces, they are efficiently killed. The article discusses at length the promise and potential of copper as a self-sanitizing material. In a 2004 study of the antibacterial, antiviral, and antifungal qualities of copper-impregnated fibers, Borkow & Gabbay [5] gave socks containing 10% copper-coated fibers to 50 individuals suffering from the fungal infection athlete’s foot. With 1-2 days of wearing the socks, all 50 individuals reported the disappearance of the burning and itching that accompanies athlete’s foot and within 2-6 days, the blistering and fissures characteristic of athlete’s foot had disappeared. Since body odor is the result of bacteria breaking down protein into certain acids on skin, it makes sense that the elimination of said bacteria by copper clothing could help prevent odor. However, as Adrian de Novato points out in his 2014 editorial about copper compression clothes, whether this is true for these particular items would depend entirely on the amount and purity of the copper used in clothing, which is something we don’t actually know [6]. Even when specific companies make claims about the percentage of copper within their clothing, we do not have a context in which to make sense of those numbers.

Research on compression garments and recovery

In 2013, Born & Holmberg [7] published a systematic review of the literature on the effects of compression clothing on athletic performance and recovery. In their analysis of 31 articles, they found evidence that the benefits of compression clothing were strongest when their purpose was for recovery, with small to moderate effects felt when applied 12 to 48 hours after significant amounts of muscle-damage-inducing exercise. Benefits included reductions in muscle swelling and perceived muscle pain as well as blood lactate removal. Also published in 2013, Driller and Hanson’s study of highly-trained cyclists found that wearing compression garments between cycling bouts might aid in reducing perceptions of muscle soreness by assisting in the clearance of metabolic waster and/or lessening the inflammatory response. Most recently, a study found that runners experienced a 6% improvement in their recovery parameters when using graduated compression socks for 48 hours after exhaustive exercise [8]. The research supports compression company claims then some of their gear can potentially improve recovery and delay the onset of muscle soreness. It should be noted that the aforementioned studies looked at lower-limb compression gear (knee-high socks, tights, shorts, or leggings) and cannot support claims for gear worn on the upper body (or underwear).

Research on compression garments and performance

In their analysis of existing compression clothing studies, Born et al. [7] found that compression wear benefitted athletes performing some strength and power exercises through improved lactate removal and improved proprioception. While they calculated small effects on improving short-duration sprints and vertical-jump height, there were no effects on peak leg power, maximal-distance throwing, balance, or arm tremble during bench press. Where endurance exercises were concerned, they could not confirm a benefit. None of the physiological markers (oxygen uptake, blood lactate concentration during continuous exercise, blood gases, or cardiac parameters) were affected by compression wear, and yet they found a small percentage of studies that demonstrated positive effects where time-to-exhaustion and trial-time performance were concerned. The authors noted that time-to-exhaustion are less reliable as a test, as well as considered the possibility of placebo effect, when considering these contradictory findings. More recently, a 2015 study found that compression garments had no effect on the performance of endurance runners; wearing lower-leg compression did not alter running mechanics or running economy in highly trained distance runners during sub maximal running [9]. Like Born et al. [7], the Stick et al. [9] study considered the possibility that responses to compression were psychological in nature, noting that the 2 subjects in their study with the greatest improvements in running economy were the only subjects who had worn compression sleeves prior to the study and already believed that compression could improve their performance and recovery.

Conclusion

The absence of scholarly inquiry into the effectiveness of copper compression sportswear appears intentional and justified. While research continues to offer limited support that compression wear in general can aid in recovery, there is not any evidence yet to support the notion that the user benefits more from copper-infused compression clothing than from non-copper alternatives, beyond the potential aesthetic benefits related to odor. Further, claims related to performance-enhancement appear to be overstated and limited to only lower-limb compression wear at this time.

Conflict of Interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Cooper L (2015) What you need to know about copper compression sleeves and pain relief. In Consumer Reports.

- Richmond SJ, Brown SR, Campion PD, Porter AJ, Moffett JA, et al. (2009) Therapeutic effects of magnetic and copper bracelets in osteoarthritis: a randomised placebo-controlled crossover trial. Complement ther Med 17(5-6): 249-256..

- Richmond SJ, Gunadasa S, Bland M, MacPherson H (2013) Copper bracelets and magnetic wrist straps for rheumatoid arthritis–analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects: A randomised double-blind placebo controlled crossover trial. PloS One 8(9): e71529.

- Grass G, Rensing C, Solioz M (2011) Metallic copper as an antimicrobial surface. Applied and environmental microbiology 77(5): 1541-1547.

- Borkow G, Gabbay J (2004) Putting copper into action: copperimpregnated products with potent biocidal activities. The FASEB J 18(14): 1728-1730.

- de Novato A (2014) What does science say? Copper compression clothes. In Science around Michigan.

- Born DP, Sperlich B, Holmberg HC (2013) Bringing light into the dark: effects of compression clothing on performance and recovery. Int J sports Physiol Perform 8(1): 4-18.

- Armstrong SA, Till ES, Maloney SR, Harris GA (2015) Compression socks and functional recovery following marathon running: a randomized controlled trial. J strength Cond Res 29(2): 528-533.

- Stickford AS, Chapman RF, Johnston JD, Stager JM (2015) Lower-leg compression, running mechanics, and economy in trained distance runners. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 10(1): 76-83.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)