- Submissions

Full Text

Researches in Arthritis & Bone Study

The Direct Anterior Approach for Total Hip Arthroplasty Without Specific Table: Surgical Approach and Our Seven Years of Experience

Gregor Kavčič, Pika Krištof Mirt, Jure Tumpej and Klemen Bedenčič*

Orthopaedic Department, General Hospital Novo Mesto, Slovenia

*Corresponding author:Klemen Bedenčič, Orthopaedic Department General Hospital Novo Mesto Šmihelska cesta, Novo Mesto, Slovenia

Submission: February 20, 2019;Published: June 14, 2019

Volume1 Issue4 June 2019

Abstract

Background: The Direct Anterior Approach (DAA) for Total Hip Arthroplasty (THA) has been gaining popularity in recent years because it is the only approach performed in both the intermuscular and the interneural planes. The number of academic articles about DAA is increasing, but still a number of authors continue to question the safety of this approach and its utilization on a day-to-day basis as a standard approach, especially because of the associated steep learning curve. In this article we describe our surgical technique and present lessons learnt from seven years of uniformly excellent experience with DAA.

Materials and Methods: The key technical steps of our surgical technique are described below: namely, surgical exposure, acetabular preparation, femoral preparation, trial reduction and definite prosthesis insertion, wound closure, and rehabilitation. We present DAA with the patient in the supine position on a regular orthopaedic table, both legs are draped free. For femoral exposure, the leg operated upon is placed in the “Figure 1” position.

Result: Between November 2010 and June 2017, we have performed 1528 THA using DAA. In the last year 400 cases, there were 379 primary THA and 21 revisions. Patients are mobilized the same day and the average length of hospitalization is three days. We observe on average ten calcar fractures per year, which can either be merely kept under observation or fixed with a single cortical screw. The rate of prosthesis dislocation is significantly below 0.5% and the rate of deep infection remained as low as with the previous approaches used.

Conclusion: In our opinion, DAA is the best approach for THA because it is the only truly minimally invasive one. It causes fewer dislocations, minimizes postoperative pain and enables faster rehabilitation without the stricter limitations when compared to other approaches.

Keywords: Direct anterior approach; Total hip arthroplasty; Minimally invasive surgery; Learning curve

Introduction

There are a number of different surgical approaches possible in regard to the hip joint and each of them is essentially sound, if the surgeon uses it routinely and strives for minimal trauma to the surrounding soft tissue. The choice of an approach is dictated largely by a surgeon’s preference, prior incisions, obesity, risk of dislocation, degree of deformity and other factors. The success of operative treatment depends on a quick recovery of limb function and the safety and reproducibility of the procedure, as well as on the alleviation of associated pain [1]. In recent years minimally invasive approaches have gained in popularity largely because they allow for the preservation of muscle, cause less surgical trauma to other soft tissues, decrease both blood loss and postoperative pain as well as limping and also permit early mobilization and rehabilitation [2-9]. The minimal incision approaches are modifications of the standard posterior, anterolateral and anterior approaches that were commonly used for hip arthroplasty. However, they are at first more demanding technically [2,5]. Some may benefit from using specially designed instruments to compensate for the reduced surgical exposure. Studies show that patient satisfaction is high, and it can be achieved without increasing complication rates [2,4,5,7]. There are several studies comparing standard and minimally invasive approaches, but definitions of minimally invasive surgery vary. Reported lengths of incisions are from 6-10cm [3]. We believe the length of incisions is a side issue, as long as we use modified surgical dissection in the inter-nervous plane while minimizing any tendon or muscle trauma during the exposure. Almost four decades ago Light & Keggi [10] described the direct anterior approach as a safe and effective one for THA with limited morbidity. In their later articles they also emphasized the clinical success of this approach which is primarily based on the sparing of the major hip muscles, their innervation and their function [6,10]. It is our considered opinion, that DAA is the only truly minimally invasive approach, because it is performed in the intermuscular and interneural planes. Utilizing this approach, no muscle disinsertion or denervation is required, which results in less hip dislocations, reduction of postoperative pain and faster rehabilitation without strict limitations [6,7,9,11]. This approach provides both perfect exposure and viewing of the acetabulum, can easily be used for bilateral THA and is easily also utilized even for very obese patients (relatively little fat tissue in the anterior peri incisional region). Disadvantages of this approach are a longer learning curve - it does take a considerable number of operations to become proficient with this approach and possible damage to the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. There is also possibly an increased risk of intraoperative fracture (i.e., of the greater trochanter, this relates to the surgeons’ experience though) and the remote possibility of injury of the femoral nerve from the retractors. DAA in the supine position without traction table has the advantages of straightforward leg-length and stability checks, does not require the presence of personnel trained to perform trauma-table maneuvers and the force needed for femoral preparation is under assistant surgeon control [8,12]. Preparation of the acetabulum and implantation of the acetabular component is a task easily achieved with standard instruments. Preparation of the femoral canal involves a careful release of the dorsal capsule, positioning the operated leg in Figure 1 position and the leveraging of the femur [8,12].

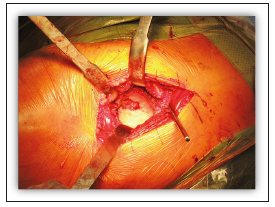

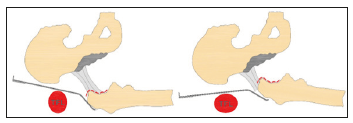

Figure 1:Acetabular exposure.

In this article we describe the technique of THA using a single, short modification of the Smith-Petersen surgical interval without using a specific table. We present key technical steps, potential issues and lessons learnt from our seven years of experience.

Materials and Methods

Patient positioning and equipment

Surgery is most often performed under general anesthesia. The patient is in the supine position on a standard operating table (Figure 2). The table is not adjusted or moved at any time during the surgery. The skin of both lower limbs is scrubbed and both legs are draped free so they can be moved during preparation of the femur. The ipsilateral arm is folded over the chest. In obese patients, abdominal fat folded over the iliac crest should be retracted using adhesive tapes. We do not use any specialized instruments to facilitate exposure. Standard Hohmann retractors are used for acetabular exposure, while for femoral exposure double offset broach handles can be used, but one could also easily utilize the single offset broach handle. In the technique described below no X-rays are needed during surgery, but we do routinely perform them the following day. We always make a preoperative radiograph templating, and, in some cases, we use computer navigation for acetabular cup positioning, which is easily incorporated with DAA.

Figure 2:The patient in supine position on a standard operating table.

Operative procedure

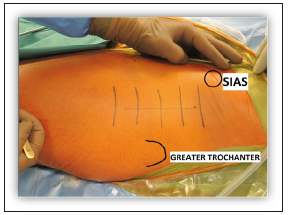

Surgical exposure: The anterior superior iliac spine (lat. Spina Iliaca Anterior Superior - SIAS) and greater trochanter are identified by palpation (Figure 3). The skin incision is modified - it does not run directly over the anterior intermuscular interval but 2-3cm lower and laterally (avoiding the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve). A straight incision starts 2cm distal and 2cm lateral to the SIAS and runs in line with the femoral shaft. The length of the incision is adjusted to the patient’s morphology. Early in the learning curve, it is safer to make a longer incision, especially since incision length does not correlate with recovery, it is important only in terms of cosmetic considerations.

Figure 3:The SIAS and greater trochanter are identified by palpation.

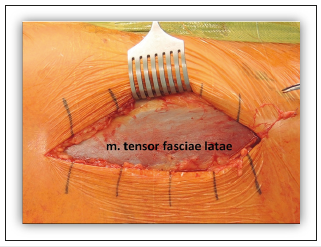

The subcutaneous tissue is incised until the tensor fasciae late muscle is seen (Figure 4). This must be performed carefully to minimize the risk of any injury to the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. Any branches of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve visible in the subcutaneous fat have to be retracted anteriorly. The fascia overlying the tensor muscle is incised longitudinally in the anterior third, then a blunt dissection between tensor muscle (lateral) and sartorius and rectus femoris (medial) is made and two retractors placed on the superior and inferior aspects of the femoral neck (extracapsular). The anterior ascending branch of the lateral circumflex artery is cauterized. Later, one retractor is placed on the roof of the acetabulum at the anterior rim, under the origin of the rectus femoris muscle. The subcutaneous fascia, which covers the fat pad overlying the capsule, is cut and the fat pad removed. The attachment of the rectus femoris muscle on the capsule is incised with a cold knife to facilitate the exposure of the anterior surface of the capsule. The hip capsule is incised in a horizontal letter-H manner and the anterior half of the capsule is removed. The superior capsule must also be released at the greater trochanter to make femoral exposure easier later during the preparation of the femur. The femoral neck is osteotomized in situ with an oscillating saw utilizing two parallel osteotomies and the resected slice of bone is removed. The femoral head is then removed with a conical corkscrew.

Figure 4:The subcutaneous tissue is incised to locate the tensor fasciae latae muscle.

Acetabular preparation: For acetabular exposure three Hohmann retractors are put in place (inferior-anterior-posterior, Figure 5). A spiked Hohmann retractor is placed on the anteriorinferior acetabular wall, under the acetabular transverse ligament. A similar Hohmann retractor is placed on the anterior acetabulum, with the spike of the retractor resting directly on the bone to avoid any possibility of femoral nerve injury. It should not be pulled too hard so as not to weaken the anterior wall. Finally, the third retractor is placed behind the posterior wall and pushes the femur away from the surgeon’s area of focus, while protecting the tensor muscle. The labrum is excised, osteophytes are removed, acetabular reaming is performed, and the cup is inserted in the usual manner. The acetabular exposure is typically excellent and bone contours can easily be controlled during the removal of osteophytes, reaming and cup placement. No special reamers are needed; we use conventional straight ones. To prevent any conflict with the psoas muscle one should be careful not to place the acetabular cup in excessive anteversion or to overhang the anterior wall.

Figure 5:“Figure 4” position of the leg.

Femoral preparation: Femoral exposure is the most demanding part of this technique and the surgeon should take time to perform it properly and safely. For femoral exposure and preparation, the leg operated upon is placed in the Figure 1 position under the contralateral leg (Figure 6), thus applying 20-30° of adduction and external rotation to the femur. A double-pronged retractor is placed posteriorly to the greater trochanter and a second retractor is placed medially. Release of the posterior joint capsule has to be performed carefully, especially in the region around the fossa piriformis, so that the femur can be lifted up with the Hohmann retractor, which is behind the greater trochanter. The femoral canal has to be directly accessible with an almost straight instrument. Only at that point can the preparation of the femoral canal begin, otherwise there is a risk of fracture of the greater trochanter. This requires a release of the thick hip capsule off the greater trochanter from the anterior to the posterior while protecting the abductors with a Hohmann retractor. Additional femoral shaft elevation can be achieved by subperiosteal release of the short external rotators. The extent of soft tissue release varies among different patients, but by proceeding step by step, satisfactory proximal femoral exposure can be gained in every patient. The broaching of the femoral canal is performed with a single or double offset broach handle, for very obese patients a double offset broach handle is a perfect solution [13].

Figure 6:Posterior joint capsule release and leverage of the femur.

Trial reduction and prosthesis insertion: Trial reduction with appropriate test head, assessment of stability in extreme ranges of movement and a leg-length check is done. The necessary adjustments can be made (neck length, stem insertion depth, bigger or smaller stem, change of offset) if required, then the prosthesis is inserted, and reduction performed. The femoral calcar is visible during stem impaction, so any unrecognized calcar fracture is avoidable. If an un-displaced calcar fracture does occur, a cerclage wire or preferably a single cortical screw can be placed in the proximal femur. We check the stability and leg-length once again together with checking for any impingement.

Wound closure: After thorough irrigation we check the surgical hemostasis and in the majority of cases a suction drain is not required. There is no need for suturing the muscles; they simply fall back into place as the retractors are removed. The fascia of the tensor muscle, subcutaneous tissue and skin are closed in layers.

Rehabilitation: After surgery the patients are observed by an anesthetist nurse in the recovery room for approximately 2 hours, before they return to the orthopaedic department. Because of pre-emptive treatment of nausea and pain using preand intraoperative medications, patients experience little pain and can usually be mobilized the same afternoon. One day after surgery we proceed with oral multimodal analgesia, based on antiinflammatory and low dose narcotic medications. Physical therapy and patient mobilization are continued the day after surgery. No hip precautions are needed, and patients can weight-bear with an assistive device for balance and safety. Patients can return home on the first postoperative day, depending on the pain and socioeconomic factors. We have regular follow-ups after one month, three months, one and a half years and then every five years after that. No outpatient physical therapy is necessary. For prophylaxis against Deep Venous Thrombosis (DVT) we use new oral anticoagulants (apixaban, rivaroxaban), early patient mobilization and intermittent calf pump exercises.

Result

In our institution we have used the Figure 1 method in the supine position since the introduction of DAA in November 2010. Before 2004 it was common practice in our hospital to perform the direct lateral approach in the supine position for THA. During residency in other hospitals one of the authors (Dr. Kavčič) learned the classic anterolateral approach, also in a supine position and in 2007 attended a course in Vienna given by Prof. Dr. Pflüger, who significantly influenced his decision to start using the minimally invasive anterolateral approach. He later adopted the direct anterior approach in a supine position without a traction table from Dr. de Witte from Belgium, whom he visited only twice and then in 2010 shifted to using the DAA without attending any cadaver courses. In 2011 Dr. Van Overschelde visited us and taught us some additional helpful techniques regarding femoral release prior to femoral neck osteotomy. In the last six years we have been using DAA for all primary THA in cases of osteoarthritis, avascular necrosis, femoral neck fractures and since 2014 also for all revision surgeries of the acetabular component and simple femoral revisions.

Between November 2010 and June 2017, we have performed 1528 THA using DAA; 1353 primary THA in cases of osteoarthritis, 61 primary THA in cases of femoral neck fractures 80 primary THA in cases of avascular necrosis and 34 revision THA in cases of acetabular loosening or simple femoral revisions. In the last two years we have performed approximately 400 primary THA and 15 revision THA a year. We have had six dislocations of prosthesis since the introduction of DAA with three of them being traumatic, after a fall from standing height or a deep squat in the early postoperative period. All dislocations were treated with reduction under general anesthesia. A single patient needed revision surgery, during which we replaced the 32mm head with a 36mm and a longer neck.

We had six fractures of the greater trochanter, all of which occurred during the first 50 cases and are attributed to the learning curve. Now we record on average ten fractures of femoral calcar per year, which are treated with screw fixation which does not affect rehabilitation in any way. The length of stay shortened since the introduction of this approach from an average of eight to three days and all of our patients are discharged home, as they do not require any additional assistance. The blood transfusion rate has lowered in the last seven years from 20% to 4%. We observe less than two early deep infections of prosthesis every year, which demand early revision surgery, debridement, exchange of mobile parts of the prosthesis and intravenous antibiotics. We have four to six superficial wound infections per year, which are above the fascia of the tensor muscle and can be treated simply by the revision of the wound, debridement and neurectomy accompanied by oral antibiotics. We perform on average seven one-stage bilateral THA per year in cases of bilateral hip osteoarthritis.

Discussion

The senior author switched to the DAA in November 2010 and since then has been using only DAA for all primary cases of THA. At first, he was still using the direct lateral approach for revision THA, then gradually adopted DAA for acetabular revisions and simple femoral revisions. Today he also uses DAA for periprosthetic femoral fractures Vancouver type A and most revision THA because of acetabular femoral loosening. We agree with Moskal et al. [7] and Mast et al. [14] regarding the limitations of using DAA in revision surgery; these being revisions of long, extensively porous-coated femoral stems, managing severe proximal bone loss and revisions of a femoral stem with significant retroversion. Revision THA in general tends to be more invasive, but the DAA and its proximal or distal extension have the potential to preserve gluteal muscle, reduce trauma to other soft tissue and reduce thromboembolic events [1,6,15].

The senior author’s learning curve was not as long as described by some other authors [11,16-18]. He recorded six fractures of the greater trochanter, which were all done during his first 50 cases and operating time also quickly became comparable to previously used approaches. We agree that the incidence of fracture decreases as the surgeon’s experience increases, and once sufficient experience has been attained, is no more common than that associated with other approaches [18]. The learning curve for mastering DAA can be demonstrated through faster surgical times, decreased intraoperative estimated blood loss, average length of hospitalization, and reduced complication rates [19]. Two other orthopaedic specialists in our institution gradually shifted to DAA during a one-year period, with no major complications. The senior author taught his orthopaedic surgery residents the DAA ‘stepwise’, and it is the only approach they have used since they started their residency. ‘Stepwise’ meaning that they first learn precisely how to begin the surgical exposure and open the hip joint, when they are comfortable with performing these steps, they progress to acetabular exposure and finally to femoral exposure which is, also in our opinion, the most demanding part of DAA [7,20]. After two years of residency our residents feel comfortable to perform the DAA for a primary THA without any major complications. In the last five years many orthopaedic surgeons from surrounding countries have visited our institution to learn the approach from the senior author. Our experiences show it is much easier to teach DAA to surgeons who already operate on patients in a supine position than those who are used to patients in a lateral decubitus position.

Improvements in the surgical technique and in perioperative anesthesia and analgesia protocols are of fundamental importance to the therapeutic success of the THA [8]. We are using a rapid recovery protocol after THA and with DAA it is easy to mobilize the patient on the very day of surgery. Consistent with prior reports, we observe improved functional recovery [9,21,22]. Uninjured muscles and muscle attachments significantly improve the dynamic muscular stabilization of the hip joint [1,21]. Patients benefit from a quicker recovery and elimination of postoperative restrictions, particularly younger and/or more active patients who need to return to work or other activities without restrictions and older patients for which a prolonged bed rest poses a significant health risk [7,11].

As reported in previous studies, the length of hospitalization has reduced since the introduction of DAA from an average of eight to three days and all our patients are discharged home. This surgical approach reduces postoperative pain, time needed to achieve physiotherapeutic goals and allows discharge to home with a considerable reduction of overall costs [8,9,23]. The average length of hospitalization can be shorter by at least two days, but in Slovenia there are usually socio-economic factors that favor the longer length of stay.

Although the majority of THAs being performed are unilateral, bilateral osteoarthritis of the hip develops in 42% of patients, necessitating replacement of both hips [24]. When a patient has equal pain in both hips and their general health is sufficient, then DAA is the best solution for one-stage bilateral THA, due to the very low rate of dislocations, minimalized blood loss and the fastest possible rehabilitation. Bilateral hip replacement can easily be performed without re-positioning the patient [7]. The study of Parvizi et al. [25] indicated that perioperative blood loss and the rate of allogenic blood transfusions are significantly lower in patients undergoing bilateral THA using DAA compared to the direct lateral approach [25]. Since the introduction of DAA in our hospital we ceased using blood salvage systems and significantly reduced the use of drains, but we have also been using tranexamic acid for three years now, which is a major factor in reducing blood loss and we record significantly lower rates of transfusions - from 20% to 4%.

In opposition to Spaans et al. [16] we register a low overall rate for complications. The dislocation rate is below 0,5% (consistent with Homma et al. [20]) and is lower than some other reports [6,18]. Clinically significant thromboembolic events are below 0,5% and the rate of deep infection is below 0,7%. DAA results in less DVT in comparison to the posterior approach because of reduced femoral vein trauma during the dislocation phase and femoral component insertion [15]. We do not routinely search for any temporary lesions of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, but less than five patients per year report numb feelings on their upper thigh and we consider this a minor complication. Post et al. [18] emphasize in their review article that damage to the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve and potential meralgia paresthetica are common, but the reported incidence ranges widely from <1% to as high as 67%. We believe these reports depend on how thoroughly the surgeons question patients postoperatively about symptoms, but most of them have only small areas of changed skin sensation and most cases largely resolve [18]. We observe on average ten calcar fractures per year, which can either be simply observed or fixed with only one cortical screw and they do not affect rehabilitation in any way. Homma et al. [20] recently published their study about chip (small fragmented) fractures of the greater trochanter, which do not require any additional operative procedure, but should be avoided nevertheless because they may increase bleeding and pain, affect the abductor mechanism or the fragmented bone tip might scratch the polyethylene, leading to more rapid polyethylene wear [20]. According to their study, chip fracture is a consequence of inadequate surgical skill and has a higher incidence during the learning curve. In their study of 109 hips, 30% of such fractures were revealed on X-rays taken two weeks after the operations. We routinely do the X-ray on the first postoperative day and after 4 four weeks, such fractures were rarely seen. Even if they were seen, we considered them to be irrelevant. When the release of soft tissue around the proximal femur is adequate, the retractor is placed under the greater trochanter and the risk for such fracture is minimized. It should be a subject of further research, especially regarding any intra-articular foreign bodies, which may cause more rapid polyethylene wear.

Computer navigation, which in our opinion is especially useful for precise positioning of the acetabular component, is easy to incorporate when utilizing the DAA. Kreuzer & Leffers [26] believe the anterior approach accommodates computer navigation better than the posterior or anterolateral approach because the patient is in the supine position throughout the procedure and does not have to be moved once calibration is complete. We use computer navigation for advanced cases, posttraumatic acetabular changes, dysplastic acetabulum and for research purposes. We find it useful and the position of the cup is very precise, but for now is still quite time-consuming, and so it is not applicable to all primary THA.

There are a few limitations to the interpretation of our results. In our institution we perform only DAA so we cannot directly compare our results with other approaches. Our data is retrospective, and comparison can only be made with the data from the approaches we used before we started using DAA. We are presenting our midterm results because we have been using DAA for seven years now. We continue to follow our patients with regular outpatient check-ups and will soon also be able to provide long-term results. There are other factors as well that improve the overall success of THA. Factors such as patient and family education, accelerated rehabilitation, patient blood management and better pain control all play important roles in influencing the outcome of minimally invasive THA [1]. A randomized large multi-centre controlled trial, comparing DAA, direct lateral and posterior approach, would provide the most reliable data.

Conclusion

Every surgical approach to the hip joint is essentially a sound approach, if the surgeon uses it routinely and strives for minimal trauma to surrounding soft tissue. In our opinion DAA is the best approach for THA, because it is the only true minimally invasive one, causes fewer dislocations, minimizes postoperative pain and enables fast rehabilitation without strict limitations. After completion of the learning curve, it can be applied to all kinds of primary cases, as well as acetabular and simple femoral revisions, all without the use of a traction table. Beginner’s tips include, beginning with appropriate patients (male, average build, long femoral neck), taking time to release the femur, being patient and persistent.

References

- Bender B, Nogler M, Hozack WJ (2009) Direct anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty. Orthop Clin N Am 40(3): 321-328.

- Howell JR, Garbuz DS, Duncan CP (2004) Minimally invasive hip replacement: rationale, applied anatomy and instrumentation. Orthop Clin N Am 35(2): 107-118.

- Cheng T, Feng JG, Liu T, Zhang XL (2009) Minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty: A systematic review. Intern Orthop 33(6): 1473-1481.

- Berger RA, Jacobs JJ, Meneghini RM, Della Valle C, Paprosky W, et al. (2004) Rapid rehabilitation and recovery with minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 429: 239-247.

- Dorr LD, Maheshwari AV, Long WT (2007) Early pain and functional results comparing minimally invasive to conventional total hip arthroplasty: A prospective, randomized blinded study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 89(6): 1153-1160.

- Kennon RE, Keggi JH, Keggi KJ (2004) The anterior approach to hip arthroplasty: The short, single minimally invasive incision. Op Tech Orthop 14(2): 85-93.

- Moskal JT, Capps SG, Scanelli JA (2013) Anterior muscle sparing approach for total hip arthroplasty. World J Orhtop 4(1): 12-18.

- Alleci V, Valente M, Crucil M, Minerva M, Pellegrino CM, et al. (2011) Comparison of primary total hip replacements performed with a direct anterior approach versus the standard lateral approach: perioperative findings. J Orthop Traumatol 12(3): 123-129.

- Mirza AJ, Lombardi Jr AV, Morris MJ, Berend KR (2014) A mini-anterior approach to the hip for total joint replacement: Optimizing results. Bone Joint J 96-B(11SupplA): 32-35.

- Light TR, Keggi KJ (1980) Anterior approach to hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 152: 255-260.

- Nöth U, Nedopil A, Holzapfel BM, Koppmair M, Rolf O, et al. (2011) Der minimal-invasive anteriore Zugang. Orthopäde 41(5): 390-398.

- Lovell TM (2008) Single-incision direct anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty using a standard operating table. J Arthroplasty 23(7Suppl1): 64-68.

- Nogler M, Krismer M, Hozack WJ, Merritt P, Rachbauer F, et al. (2006) A double offset broach handle for preparation of the femoral cavity in minimally invasive direct anterior total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 21(8): 1206-1208.

- Mast NH, Laude F (2011) Revision total hip arthroplasty performed trough the Heuter interval. J Bone Joint Surg Am 93(2): 143-148.

- York PJ, Smarck CT, Judet T, Mauffrey C (2016) Total hip arthroplasty via the anterior approach: Tips and tricks for primary and revision surgery. Intern Orthop 40(10): 2041-2048.

- Spaans AJ, van den Hout JAAM, Bolder SBT (2012) High complication rate in the early experience of minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty by the direct anterior approach. Acta Orthopaedica 83(4): 342-346.

- Rodriguez JA, Deshmukh AJ, Rathod PA, Greiz ML, Deshmane PP, et al. (2014) Does the direct anterior approach in THA offer faster rehabilitation and comparable safety to the posterior approach? Clin Orthop Relat Res 472(2): 455-463.

- Post ZD, Orozco F, Diaz-Ledezma C, Hozack WJ, Ong A (2014) Direct anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty: Indications, technique, and results. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 22(9): 595-603.

- York PJ, Logterman SL, Hak DJ, Mavrogenis A, Mauffrey C (2017) Orthopaedic trauma surgeons and direct anterior total hip arthroplasty: Evaluation of learning curve at a level I academic institution. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 27(3): 421-424.

- Homma Y, Baba T, Ochi H, Ozaki Y, Kobayashi H, et al. (2016) Greater trochanter chip fractures in the direct anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 26(6): 605-611.

- Mayr E, Nogler M, Benedetti MG, Kessler O, Reinthaler A, et al. (2004) A prospective randomized assessment of earlier functional recovery in THA patients treated by minimally invasive direct anterior approach: A gait analysis study. Clin Biomech 24(10): 812-818.

- Taunton MJ, Mason JB, Odum SM, Springer BD (2014) Direct anterior total hip arthroplasty yield more rapid voluntary cessation of all walking aids: a prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Arthroplasty 29(9):169- 172.

- Goebel S, Steiner AF, Shillinger J, Euler J, Broscheit J, et al. (2012) Reduced postoperative pain in total hip arthroplasty after minimalinvasive anterior approach. Int Orthop 36(3): 491-498.

- Saito S, Tokuhashi Y, Ishii T, Mori S, Hosaka K, et al. (2010) One-versus two-stage bilateral total hip arthroplasty. Orthopedics 33(8).

- Parvizi J, Rasouli MR, Jaber M, Chevrollier G, Vizzi S, et al. (2013) Does the surgical approach in one stage bilateral total hip arthroplasty affect blood loss? Intern Orthop 37(12): 2357-2362.

- Kreuzer S, Leffers K (2011) Direct anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty using computer navigation. Bull NYU Hops Jt Dis 69(1): S52-S55.

© 2019 Klemen Bedenčič. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)