- Submissions

Full Text

Perceptions in Reproductive Medicine

Birth Experience, Social Capital, Self- Compassion and Wellbeing in Mothers in The First Year Post-Partum

Tony Cassidy* and Justine McCrory

Professor Emeritus of Child & Family Health Psychology, Ulster University, USA

*Corresponding author:Tony Cassidy, Professor Emeritus of Child & Family Health Psychology, Ulster University, USA

Submission: February 15, 2024;Published: March 15, 2024

ISSN: 2640-9666Volume6 Issue1

Abstract

Problem: While research has focused on negative psychological effects of childbirth, the factors that might

mediate positive psychological effects are less well known and have important implications for supporting

mothers.

Background: Childbirth can have an immediate and longer-term consequences for the wellbeing of

mothers and their experiences can be overshadowed by a focus on the new baby. While physical needs of

mothers postpartum may be fulfilled, psychological needs can be overlooked.

Aim: To explore the relationship between birth experience, perceived social capital (sense of community,

social support, attachment style), self-compassion, and wellbeing in mothers who had experienced giving

birth within the previous twelve months.

Methods: An online survey using questionnaire data collection assessed 270 women ranging in age 22-41

years on measures of birth experience, sense of community, social support, self-compassion, attachment

style, and wellbeing.

Findings: Perceived social capital and self-compassion are related to wellbeing of mothers in the firstyear

post-partum. Hierarchical multiple regression analysis showed that support and self-compassion,

can increase wellbeing and mediate the impact of negative birth experiences.

Discussion: Multifaceted social support and self-compassion seem to provide protection against guilt

and self-blame which are major factors in post-partum distress and might usefully inform psychological

support for mothers at this time.

Conclusion: The current study highlights the importance of looking at support in a broad context and

considering the potential for self-compassion in preparing for birth and in preventing the development of

negative psychological consequences.

Keywords:Birth experience; Social capital; Self-compassion; Wellbeing

Statement of Significance

I. Problem or Issue: Poor birth experience has both short- and long-term- consequences

for the health and wellbeing of mother and baby.

II. What is Already Known: Lack of perceived support and low self-esteem are implicated

in poor birth experience.

III. What this Paper Adds: This paper takes a preventive focus and looks at what might

prevent a poor psychological experience of birth, and may also reduce the negative effects

of the birth experience.

Introduction

Motherhood does not just begin with the birth of a baby [1], and for those who experience infertility and miscarriage the transition to motherhood may be spread over many years [2]. Birth is one of the most common life transitions experienced by women, often signifying a period of great disruption [3]. According to other researchers, “Childbirth is a major life event with reverberating implications for the health of the family” [4]. Two of the main factors in post-partum depression are a traumatic birth experience and a lack of social support [5]. Postpartum depression is linked with poor mother-child attachment bonding and may have longer term developmental consequences if not recognised [6]. Mother’s own adult attachment security also impacts on birth experience and development of attachment with the child [7]. Though women have more opportunity, social isolation and lack of support can be a real problem [8,9], due to distance from extended family and a bundle of expectations to be managed independently [10]. These expectations can generate a no-win situation and feelings of inadequacy, and this can in turn inhibit women from seeking support due to fears of being seen as a bad, or incapable mother [11]. The level of guilt and self-blame experienced by mothers postpartum is generally underestimated and unacknowledged [12-15], and is implicated in distress and depression [16].

Whereas self-blame is seen as damaging there is a growing literature to attest to self-compassion as beneficial [17]. Selfcompassion entails unconditional self-worth and is nonjudgemental to failures [18-20]. It involves treating oneself with kindness, recognizing one’s shared humanity, and being mindful when considering negative aspects of oneself [21,22], and is strongly related to wellbeing [17]. Self-compassion is related to more stable romantic relationships [23,24], to more compassion towards others [25,26], and partners [23], to increased support giving [27], to more secure attachment [28], and to increased social support [29]. Social capital has been shown to mediate the impact of psychological distress [30], and increase wellbeing [31]. The term social capital originates in sociology and is variously defined as ‘resources embedded in social networks’ [30], or ‘the forces that shape the quality and quantity of social interactions and social institutions’ [32]. Social capital does not have a clear, undisputed meaning [33], but the commonalities of most definitions of social capital are that they focus on social relations that have productive benefits. It is the perception or appraisal of support rather than actual support which has the strongest link to health and wellbeing [34], so we have chosen to refer to perceived social capital as the appraisal of support received or available from a variety of resources. In this case from partner, family, friends, significant others, from community, and the resources available in relations.

Perceived social support results in the recipient of that support feeling cared for, valued, and having a sense of belonging [11,35- 38]. Social support may be provided by partners, family, peers, colleagues, or others in the community and offers protection of the physical, mental, and emotional well-being of people experiencing stress [11]. Social support is especially important at times of life change such as transitioning to motherhood [10]. Research has shown that social support is vital in promoting well-being in the postnatal period, and that this is most beneficial to mothers when family, friends, and partners are addressing this need [11,39]. Attachment state of mind of the individual is the way in which adults process thoughts and feelings regarding their own attachment experiences [40-42] and is causally related to the development of adult relationships. One model and measure of attachment in relationships reflects the way individuals feel about the relationships in their life [43]. The dimensions measured are Close (the extent to which a person is comfortable with closeness and intimacy), Depend (whether the person feels they can depend on others to be available when needed), and Anxiety (the extent to which a person is worried about being abandoned or unloved). These dimensions are important in terms of perceived social capital because they reflect how the person will react to and receive support.

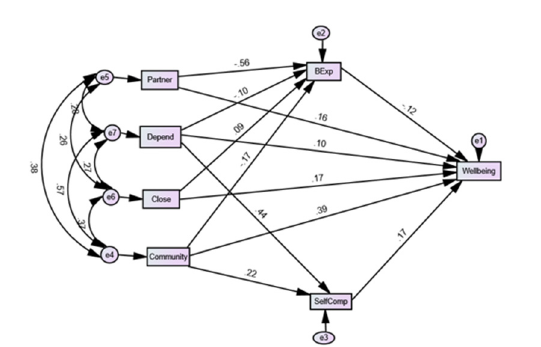

Figure 1:Path model of wellbeing SelfComp=Self-compassion, BExp=Birth experience.

The early postpartum period has been identified as an important focus for research, yet the well-being of the mother is not a major focus [44]). Feelings of guilt, or an inability to admit when one needs help may be barriers to accessing support. Research therefore must focus not only on the role of support in the health and wellbeing of the postpartum mother, but also the mitigating factors which allow her to access these supports in a healthy manner (Figure 1). The current study aimed to explore the relationship between birth experience, perceived social capital (sense of community, social support, attachment style), self-compassion, and wellbeing in mothers who had experienced giving birth within the previous twelve months.

Method

Design

This study employed a questionnaire to examine the role of perceived social capital and self-compassion in maternal wellbeing during the first year postpartum. Participation was voluntary and the questionnaire was distributed via parenting groups on Facebook as well as the University email system. A G*Power analysis was conducted to determine the sample size. Using a medium effect size (f2= .15), power set at .8, and alpha = .05, G*Power indicated that a sample of 98 participants was necessary. The inclusion criteria for participants were women who had had a baby in the past 12 months. It did not need to be the woman’s first baby to partake in the study. A total of 270 mothers completed the survey.

Materials

Demographic variables were compiled by the researchers into a form which asked about age of mother (18-41; Mean= 28.9, Sd = 4.5), number of children (1 = 133, 2=83, 3=36, 4=18), age of youngest child (3-12 months; Men = 7.5, Sd = 2.4), age of mother when she first gave birth (17-35; Mean = 27.6, Sd= 4.2), marital status (married =185, unmarried = 54, divorced =31), education (primary = 26, secondary lower =46, secondary higher = 124, tertiary = 43, postgraduate = 31), if youngest breast fed (Yes =207, No= 63), if baby was premature (Yes =33, No= 237), if baby needed medical treatment (Yes= 47, No=223).

Then participants completed the following measures. The Birth Experience Questionnaire [4] is a 10-item measure which is used to assess stress, fear, and partner support during birth with responses rated on a Likert Scale. The scale asked the participant to think “about your most recent birth” and rate statements which best reflected that experience with responses rated from 1- strongly disagree to 7- strongly agree. The two items related to partner support can be separated into a brief partner support measure. Items were scored so that a higher score indicates more support. The other eight items reflect recalled memories of the birth experience and were scored so that a higher score indicates a more negative experience. The latter eight item scale had a Cronbach’s Alpha of .76 in the current data. The two-item partner support measure had a Cronbach Alpha of .71 in this data.

Sense of Community was assessed using the Brief Sense of Community Scale (BSCS) [45]. The BSCS is an 8-item scale self-report which measure 4 domains of sense of community including: (1) Membership, (2) Influence, (3) Fulfilment of needs, (3) Shared Emotional Connection. The scale employs 5-point Likert-type scoring. The scale had an Alpha of .83 in the current data. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support Scale (MSPSS) [46] is a 12-item self-report inventory which assesses the respondent’s perception of social support adequacy (e.g. How often do you feel as if nobody really understands you?) Three subscales address the respondents perceived support from: (1) Family (Cronbach Alpha = .86), (2) Friends (Cronbach Alpha = .91) and (3) Significant Others (Cronbach Alpha = .84), using a 5-point Likert scale (0=Never, 1=Seldom, 2=Sometime, 3=Often, 4=Always). The internal reliability of the overall MSPSS has demonstrated a coefficient α = .93 [47].

The Self-Compassion Scale-short form (SCS-SF) [48,49]) is a 12-item self-report inventory which measures how one typically acts towards oneself in difficult times (e.g. When I fail at something that’s important to me, I tend to feel alone in my failure). Responses are measured using a 5-point Likert scale (0=Almost Always to 4=Almost Never). The SCS-SF has demonstrated satisfactory reliability among Dutch and English samples (α = 0.86; [49] α =0.84 in the current data). The Adult Attachment Style Questionnaire [43,50] is made up of 18 questions containing 3 subscales which measure Close (α =0.84), Depend (α =0.72), and Anxiety (α =0.74). Close refers to the extent to which a person is comfortable with closeness and intimacy, depend refers to whether the person feels they can depend on others to be available when needed, and anxiety measures the extent to which a person is worried about being abandoned or unloved. Each of the questions is rated on a Likert scale from 1; not at all characteristic of me to 5; very characteristic of me.

The Warwick Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale-short form which is made up of seven positively worded items that relate to the different aspects of positive mental health. Each item was rated based on the experience of the respondent over the past two weeks, with items being ranked on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = None of the Time to 5 = All of the Time. The summed item scores were used to determine the level of positive mental well-being, with a higher score indicative of a higher level of positive mental wellbeing. The scale had a Cronbach Alpha of .85 in this data.

Procedure

Ethical approval was obtained from the School of Psychology Research Ethics Committee. The questionnaire was uploaded to Qualtrics (an online survey platform) and distributed via a link to Parenting Groups in UK, on social media (Facebook and twitter) as well as via the University email system. The questionnaire included a Participant Information Sheet containing general information about the research aims and a consent form which needed to be completed before continuing to the questionnaire. This enabled the researchers to be sure that the participants were fully informed and agreed consent before participating.

Result

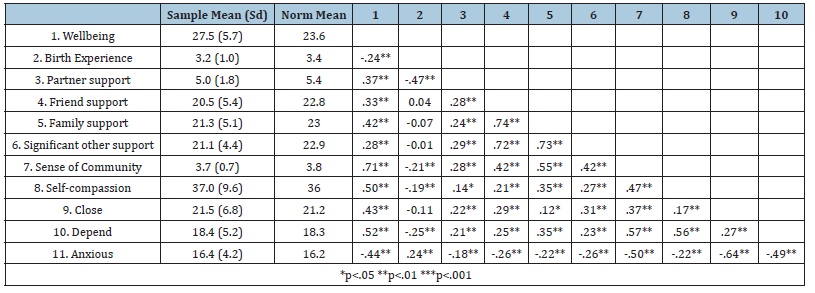

The current study aimed to explore the relationship between birth experience, sense of community, social support, self compassion, attachment style, and wellbeing in mothers who had experienced giving birth within the previous twelve months. The first analysis involved calculating descriptive statistics and correlations as shown in Table 1. Experience of birth was scored so that a higher score indicated a more stressful birth experience. Wellbeing was inversely related to birth experience and anxiety about relationships. It was directly correlated with support from partner at birth, perceived support from family, friends, and significant others, a sense of identity with the community, self-compassion, and feeling comfortable with being close in relationships and of feeling able to depend on others to be available if needed. This provides evidence for the importance of perceived social capital.

Table 1:Zero order correlations and descriptive statistics.

Table 1 to explore how the current sample relates to the general population we identified mean scores on the measured variables which were drawn from more normative populations. One sample t-tests were used to test the means from the current study against these normative population means. For wellbeing our sample scored significantly higher than the population means devised by Ng Fat, Scholes, Boniface, Mindell and Stewart-Brown [47], (t (269) =11.144, p<.001). On self-compassion our sample didn’t differ significantly from the norm [49], (t (269) =1.719, p=.09). For Birth Experience our sample scored significantly lower than the population norm [4], (t (269) =3.627, p<.001). Our sample scored significantly lower than the norm on partner support at birth [4] (t (269) =3.824, p<.001). On Sense of Community our sample scored significantly lower than norm [49] (t (269) =1.993, p<.05). For Support from Family our sample scored significantly lower than the population norm [46] (t (269) =7.67, p<.001). Our sample scored significantly lower than the norm on Support from Friends (t (269) =4.819, p<.001) and Support from a Significant Other (t (269) =6.954, p<.001) [46]). Finally in terms of the dimensions of attachment [43], our sample did not differ significantly from the norm on Close (t (269) =0.682, p<=.496), Depend (t (269) =0.283, p=.778), and Anxiety (t (269) =0.753, p=.452).

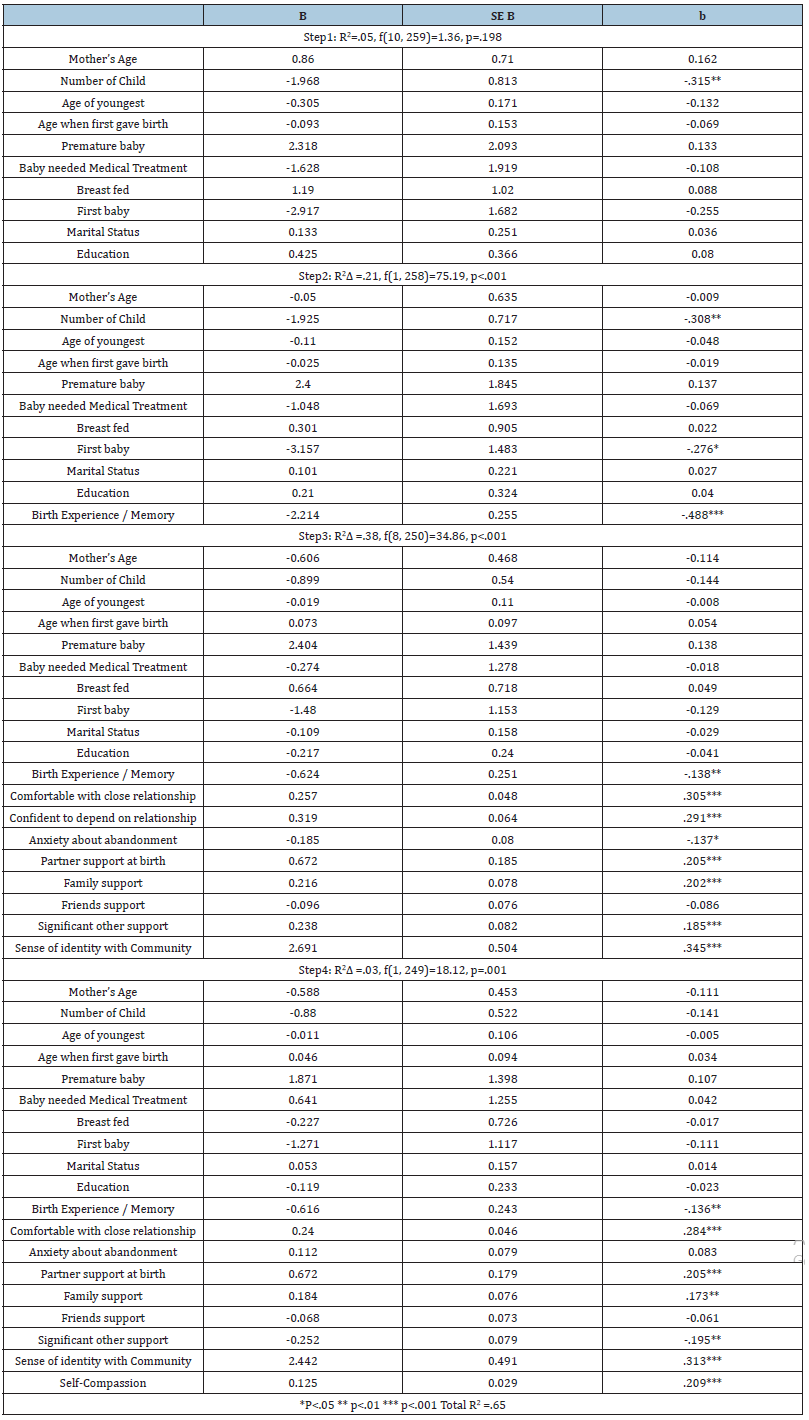

To explore these relationships more fully Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analysis (HMRA) was used with wellbeing as the dependent variable (Table 2). Age of mother, number of children, age of youngest child, age of mother when she first gave birth, marital status, education, if youngest breast fed, if baby was premature, if baby needed medical treatment, were entered as predictor variables in step one and accounted for 5% of the variance, however this was not significant. However, number of children and whether this was the first baby did have a significant partial correlation with wellbeing in the direction that having less children (β =-.315, p<.01) and this being the first child ((β =-.255, p<.01) was related to higher wellbeing. Birth experience / memory was added on the second step and accounted for an additional 21% of the variance in wellbeing (β =-.488, p<.001). More negative memories of the birth experience related to lower wellbeing.

Table 2:Hierarchical multiple regression analysis with wellbeing as dependent variable.

The social relationship variables (social capital), being comfortable with close relationships, being confident of depending on social relationships, anxiety about abandonment, partner support at birth, family support, friend support, support from significant other, and sense of identity with community were added on step three and between them accounted for a further 38% of the variance in wellbeing. Variables with significant partial correlation were being comfortable with close relationships (β =.305, p<.001), being confident of depending on social relationships (β =.291, p<.001), anxiety about abandonment (β =-.137, p<.05), partner support at birth (β =.205, p<.001), family support (β =.202, p<.001), support from significant other (β =.185, p<.001), and sense of identity with community (β =.305, p<.001). In essence having a perception of a broad range of supportive relationships contributed to improved wellbeing. When the social capital variables were added the partial correlations for number of children and first baby were reduced to non-significance suggestion a moderation effect.

Self-compassion was entered on step three and accounted for 3% of the variance, (β =.209, p<.001). Overall, the model predicted 65% of the variance in wellbeing. To further test these relationships a path model was built and tested using Structural Equation Modelling with AMOS 25. The model was based on the significant partial ++ Fit statistics for the model were chi-square = 0.38, p=.943, CMIN/DF = 0..129, GFI = 1.0, NFI = .99, IFI = 1.0, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00, PCLOSE = .977. The model was an excellent fit for the data.

Discussion

The findings from this study show that perceived social capital and self-compassion are related to wellbeing of mothers in the first-year post-partum. In addition, perceived social capital and self-compassion appear to mediate the impact of a negative birth experience. These findings are consistent with previous research which has found social support to be an integral part of a mother’s well-being during the postnatal period [39]. We went beyond the traditional measure of social support and included measures of partner support at birth, support from family, friends and significant others, mothers’ perception of their relationships, and sense of identity with the community. It seems that a combination of support from family and significant other, partner support at birth, being comfortable in a close relationship, having a sense of being able to depend on relationships, and identifying with the community are related to wellbeing. This combination, which we refer to as perceived social capital, also mediates the remembered negative birth experience. Furthermore, self-compassion is related to wellbeing and seems to play a mediating role.

Previous research suggested that a major factor after birth for mothers is guilt and self-blame [14,15] which is implicated in postpartum distress [12,16]. Self-compassion is the antithesis to blame and guilt and involves self-kindness and acceptance of being human. The fact that it is associated with wellbeing and seems to mediate negative birth experience suggests potential for intervention [50]. Some early research suggests that mindful selfcompassion interventions can prevent postpartum depression. There is good evidence of the preventive potential for selfcompassion- based interventions across a wide range of populations. In agreement with previous research, the current study found that perceived social capital was crucial in promoting the well-being of a mother during her first year after childbirth [8,11]. This suggests that having access to a range of types of support during the first year after childbirth can dramatically influence the well-being of the mother.

Conclusion and Recommendation

Our findings suggest that considering support in terms of perceived social capital provides some insight into the range of support that can provide a nurturing context for motherhood. In addition, the role of self-compassion as a buffer to feelings of guilt and self-blame that are prevalent around and post-partum extends the evidence base and provides a signpost to potential interventions that may be beneficial in preparing for birth, and in alleviating any potential distress.

References

- Mares S, Newman L, Warren B (2011) Clinical skills in infant mental health. In: (2nd edn), Victoria, ACER Press, UK.

- OKane E, Cassidy T (2019) Losing an unborn baby: Support after miscarriage. Journal of Family Medicine Forecast 2(3): 1-6.

- Suetsugu Y, Haruna M, Kamibeppu K (2020) A longitudinal study of bonding failure related to aspects of posttraumatic stress symptoms after childbirth among Japanese mothers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 20(1): 434.

- Saxbe D, Horton KT, Tsai AB (2018) The birth experiences questionnaire: A brief measure assessing psychosocial dimensions of childbirth. Journal of Family Psychology 32(2): 262-268.

- O Hara MW (2009) Postpartum depression: What we know. Journal of Clinical Psychology 65(12): 1258-1269.

- Smith NJ, Tharner A, Steele H, Cordes K, Mehlhase H, et al. (2016) Postpartum depression and infant-mother attachment security at one year: The impact of co-morbid maternal personality disorders. Infant Behavior and Development 44: 148-158.

- Reisz S, Brennan J, Jacobvitz D, George C (2019) Adult attachment and birth experience: importance of a secure base and safe haven during childbirth. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology 37(1): 26-43.

- Chavis L (2016) Mothering and anxiety: Social support and competence as mitigating factors for first-time mothers. Social Work in Health Care 55(6): 461-480.

- Heaperman A, Andrews F (2020) Promoting the health of mothers of young children in Australia: A review of face to face and online support. Health Promotion Journal of Australia 31(3): 402-410.

- Machado TD, Chur HA, Due C (2020) First-time mothers’ perceptions of social support: Recommendations for best practice. Health Psychology Open 7(1): 205510291989861.

- Dunford E, Granger C (2017) Maternal guilt and shame: Relationship to postnatal depression and attitudes towards help-seeking. Journal of Child and Family Studies 26: 1692-1701.

- Jackson L, De Pascalis L, Harrold J, Fallon V (2021) Guilt shame, and postpartum infant feeding outcomes: A systematic review. Maternal & Child Nutrition 17(3): e13141.

- Jackson L, Fallon V, Harrold J, De Pascalis L (2022) Maternal guilt and shame in the postpartum infant feeding context: A concept analysis. Midwifery 105: 103205.

- Shuman CJ, Morgan ME, Chiangong J, Pareddy N, Veliz P, et al. (2022) Mourning the experience of what should have been: experiences of peripartum women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Maternal and Child Health Journal 26(1): 102-109.

- Coates R, Ayers S, Visser R (2014) Women's experiences of postnatal distress: a qualitative study. BMC pregnancy and Childbirth 14: 359.

- Bluth K, Blanton PW (2015) The influence of self-compassion on emotional well-being among early and older adolescent males and females. The Journal of Positive Psychology 10(3): 219-230.

- Leary MR, Tate EB, Adams CE, Batts Allen A, Hancock J (2007) Self-compassion and reactions to unpleasant self-relevant events: The implications of treating oneself kindly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 92(2): 887.

- Neff KD, Germer C (2017) Self-compassion and psychological wellbeing. In: J Doty (Eds), Oxford Handbook of Compassion Science, Oxford University Press, USA.

- Munroe M, Al-Refae M, Chan HW, Ferrari M (2022) Using self-compassion to grow in the face of trauma: The role of positive reframing and problem-focused coping strategies. Psychological trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 14(S1): S157-S164.

- Bolt O, Jones F, Rudaz M, Ledermann T, Irons C (2019) Self-compassion and compassion towards one's partner mediate the negative association between insecure attachment and relationship quality. Journal of Relationships Research 10: E20.

- Neff KD, Beretvas SN (2013) The role of self-compassion in romantic relationships. Self and Identity 12(1): 78-98.

- López A, Sanderman R, Ranchor A, Schroevers M (2018) Compassion for others and self-compassion: Levels, correlates and relationship with psychological wellbeing. Mindfulness 9: 325-331.

- Breines JG, Chen S (2013) Activating the inner caregiver: The role of support-giving schemas in increasing state self-compassion. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 49(1): 58-64.

- Wei M, Liao K, Ku T, Shaffer PA (2011) Attachment, self-compassion, empathy, and subjective well-being among college students and community adults. Journal of Personality 79(1): 191-221.

- Toplu D, E Kemer G, Pope AL, Moe JL (2018) Self-compassion matters: The relationships between perceived social support, self-compassion, and subjective well-being among LGB individuals in Turkey. Journal of Counseling Psychology 65(3): 372-382.

- Song L (2011) Social capital and psychological distress. Journal of Health and Social Behaviour 52(4): 478-492.

- Gong S, Xu P, Wang S (2021) Social capital and psychological well-being of Chinese immigrants in Japan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18(2): 547.

- McKenzie K, Whitley R, Weich S (2002) Social capital and mental health. British Journal of Psychiatry 181(4): 280-283.

- Dolfsma W, Dannreuther C (2003) Subjects and boundaries: Contesting social capital-based policies. Journal of Economic Issues 37(2): 405-413.

- Cohen S, Gottlieb B, Underwood L (2000) Social relationships and health. In: S Cohen, L Underwood & B Gottlieb (Eds.), Social Support Intervention and Measurement, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, pp. 3-25.

- Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL (1991) The MOS social support survey. Social Science & Medicine 32(6): 705-714.

- Taylor SE (2011) Social support: A review. Oxford Handbooks Online, USA.

- Uchino BN, Uno D, Holt-Lunstad J (1999) Social support, physiological processes, and health. Current Directions in Psychological Science 8(5): 145-148.

- Gjesfjeld CD, Weaver A, Schommer K (2012) Rural women's transitions to motherhood: Understanding social support in a rural community. Journal of Family Social Work 15(5): 435-448.

- Razurel C, Kaiser B, Sellenet C, Epiney M (2013) Relation between perceived stress, social support, and coping strategies and maternal well-being: A review of the literature. Women & Health 53(1): 74-99.

- Larose S, Bernier A, Tarabulsy GM (2005) Attachment state of mind, learning dispositions, and academic performance during the college transition. Developmental Psychology 41(1): 281-289.

- Maier MA, Bernier A, Pekrun R, Zimmermann P, Strasser K (2005) Attachment state of mind and perceptual processing of emotional stimuli. Attachment & Human Development 7(1): 67-81.

- Collins NL, Read SJ (1990) Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 54: 644-663.

- Currie J (2009) Managing motherhood: strategies used by new mothers to maintain perceptions of wellness. Health Care for Women International 30(7): 653-668.

- Peterson NA, Speer PW, Mcmillan DW (2008) Brief sense of community scale. PsycTESTS Dataset.

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK (1988) Multidimensional scale of perceived social support. PsycTESTS Dataset.

- Canty Mitchell J, Zimet GD (2000) Psychometric properties of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support in urban adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology 28(3): 391-400.

- Neff KD (2015) The self-compassion scale is a valid and theoretically coherent measure of self-compassion. Mindfulness, 7(1): 264-274.

- Raes FD, Pommier EV, Neff K, Gucht D (2010) Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the self-compassion scale. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy 18(3): 250-255.

- Collins NL (1996) Revised adult attachment scale. PsycTESTS Dataset.

- Tennant R, Hiller L, Fishwick R, Platt S, Joseph S, et al. (2007) The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): development and UK validation. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 5(63): 1-13.

- Ng Fat L, Scholes S, Boniface S, Mindell J, Stewart BS (2017) Evaluating and establishing national norms for mental wellbeing using the short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS): findings from the Health Survey for England. Quality of life research: An International Journal of Quality-of-Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation 26(5): 1129-1144.

- Fernandes DV, Canavarro MC, Moreira H (2021) The role of mothers' self-compassion on mother-infant bonding during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal study exploring the mediating role of mindful parenting and parenting stress in the postpartum period. Infant Mental Health Journal 42(5): 621-635.

- Guo L, Zhang J, Mu L, Ye Z (2020) Preventing postpartum depression with mindful self-compassion intervention: A randomized control study. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 208(2): 101-107.

- Ferrari M, Hunt C, Harrysunker A, Abbott MJ, Beath AP, et al. (2019) Self-compassion interventions and psychosocial outcomes: a Meta-Analysis of RCTs. Mindfulness 10: 1455-1473.

© 2023 Tony Cassidy. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)