- Submissions

Full Text

Perceptions in Reproductive Medicine

Post-Partum AKI Unrelated to the Pregnancy

Behrooz Broumand1*, Bahram Moazzami2, Maryam Shahroukh3, Farank Ghasemi4 and Varshasb Broumand5

1Emeritus Professor of Medicine, Pars Advanced and Minimally Invasive Manners Research Center, Iran

2Managing director Pars General Hospital, President Pars Advanced and Minimally Invasive Manners Research Center, Iran

3Director of Dialysis Unit Pars Hospital , Pars Advanced and Minimally Invasive Manners Research Center, Pars General Hospital, Iran

4Pars Advanced and Minimally Invasive Manners Research Center, Pars General Hospital, Iran

5South Texas Renal Care Group, USA

*Corresponding author:Behrooz Broumand, Emeritus Professor of Medicine, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Pars Advanced and Minimally Invasive Manners Research Center, Pars General Hospital, Iran

Submission: August 08, 2022;Published: September 13, 2022

ISSN: 2640-9666Volume5 Issue3

Abstract

In Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) during pregnancy or after termination of pregnancy different etiologies should be considered. The approach to a pregnant woman with Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) is very important and should include a detailed history and physical examination plus adequate knowledge of hazards during different trimesters of pregnancy and post-partum. We describe a case of post-partum AKI which is not related to pregnancy while manifested right after delivery.

Keywords:Post-partum; Pregnancy; Delivery; Obstetrician; Morbidity; Clinicians

Abbreviations: AKI: Acute Kidney Injury; SLE: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus; NSAIDs: Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatories; ACE: Angiotensin Converting Enzyme

Introduction

Conception is a physiological event usually with good and promising outcome. However, conception can turn into a harmful event with morbidity and mortality. Usually, termination of pregnancy either vaginal or via C-section will decrease the risk to the mother. Rarely, postpartum there will be some risk to the mother. This post-partum risk is known to both the obstetrician and other clinicians, and usually the risk is related to pregnancy or delivery. We are describing a preventable risk for the kidney after delivery which was not due to pregnancy or delivery. Knowledge about this risk can result in a decrease in morbidity.

Case Report

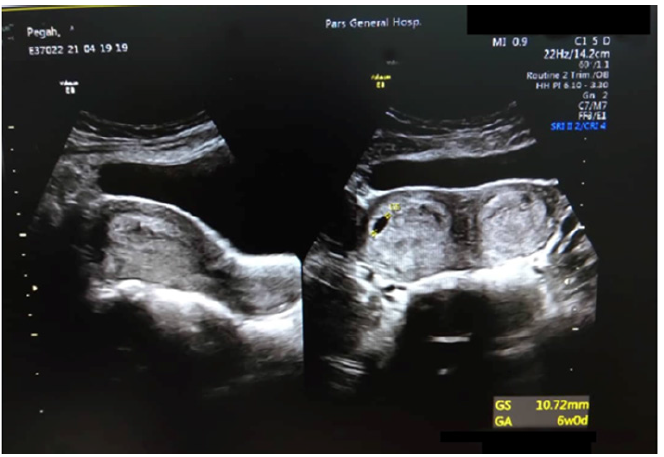

A 29 year old pregnant woman was admitted to the obstetric ward of a general hospital for a C-section of her first pregnancy on Sept.13, 2019. On admission, the patient was in good health, well developed, well-nourished and had no past medical history of kidney or metabolic diseases. Oral temperature was 37° centigrade, pulse rate was regular at 88 beats/min and her supine blood pressure in the right arm was 120/70mmHg. She had no lower extremity edema, and the rest of her physical exam was non-revealing. On laboratory evaluation, her serum creatinine was 0.55mg/dl and her urinalysis was normal. Pelvic ultrasonography during pregnancy (Figure 1) demonstrated a didelphis uterus [1]. *She underwent a low C-Section and had healthy baby boy with an Apgar score of 9; height was 51cm and weight was 3.10kg. The patient was discharged on Sept.15,2019, afebrile with a supine BP of 110/60mmHg in the right forearm, pulse rate was regular at 88 per min regular. There were no concerning health issues on discharge.

Figure 1: Insufflation test-sample A.

Four days later, the patient presented to the emergency room with severe headache, mild respiratory distress and generalized edema. On physical examination, the patient was 70kg, the supine blood pressure in the right arm was 185/95mmHg. Her oral temperature was 36° centigrade, pulse rate was 100 beats/minute, and respiratory rate was 24 per minute. Her face was flushed; she was tachycardic, and her lungs were clear to auscultation with no dullness to percussion. Her abdomen was soft and non- tender, and she had no CVA tenderness. She had 2+ pitting edema in her lower extremities. The patent was given 2 doses of 5mg Hydralazine injection and blood pressure decreased to 140/86 supine right arm. Laboratory evaluation was as follows, wbc 10,100/mm3 with a differential count of 77.4% polys, 15.2% lymphs, 6.4% monos, 0.8% eosinophils, and 0.2% basophils. Her hemoglobin was 10.9g/ dl with a hematocrit of 31.6% and a platelet count 328,000/mm3. Prothrombin time was 13sec. with an INR of 1.009, BUN 25mg/ dl, and serum creatinine was 1.7mg/dl. Repeat confirmatory laboratory investigation revealed serum creatinine to be 1.8g/dl, uric acid 6.3mg/dl, Na 141mEq/L, K⁺ 4.0mEq/L, Cl⁻ 108mEq/L, alkaline phosphatase 102 U/L, AST 23IU/L, and ALT 22IU/L. Urinalysis revealed clear urine with a specific gravity of 1.010, 1+ protein, negative glucose and on microscopic exam 6-8wbc and 5-6rbc/hpf. 24 hours urine volume was 3250ml with a creatinine 1365mg/24hr and a corrected creatinine clearance 54.5cc/min.

To diagnose the etiology of post-partum AKI, the patient underwent a work-up for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE), systemic illness and infection. ANA, Anti double stranded DNA and serum complement were all within normal limits and all other laboratory results were non-revealing. On further questioning, it was found that after discharge from the hospital in order to increase the production of breast milk for breast feeding the patient started heavy drinking of milk and juices, and as a result, on the third day after discharge, she developed pedal edema and puffiness of the face followed by severe headache. She subsequently took plenty of advil plus mefenamic acid. Diagnosis of analgesic induced nephropathy was made. All analgesics were discontinued, and fluid intake was restricted. Her edema rapidly resolved. Supine blood pressure decreased to 140/80mmHg. On Sept. 23, 2019, she was discharged from the hospital in good health with a Hgb of 10.7g/ dl, Hct of 30.9%, platelet count 398000/mm3, BUN 23mg/dl, serum Cr.1.3mg/dl, Na 148mEq /L, and a serum K⁺ 4.4mEq/L .

Urinalysis results

Appearance clear, pH of 7.0, specific gravity 1.005, protein trace, negative glucose, and 2+ blood. On microscopic exam: wbc 8-10/Hpf, RBC 12-14 /Hpf. No cast were reported. Urine culture reported as no growth.

Discussion

Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) is one of the most dreadful potential complications during pregnancy and occasionally post-partum with a substantial unpleasant impact on the outcome of pregnancy, endangering the life of the mother and the fetus. This complication is usually related to conception. But, obstetricians and nephrologists should be aware of the occurrence of post-partum complications unrelated to pregnancy and delivery. AKI is defined as a prompt decrease in renal function over a period of several hours to days and could result in proteinuria followed by decreased renal function as evidenced by retention of waste products. AKI-related mortality in pregnancy is between 25 and 30%. As renal function during pregnancy is different compared to non-pregnant women, the diagnosis of AKI could be difficult if the clinician is not familiar with physiologic changes of renal function during pregnancy. It is well known that in pregnancy the BUN, serum creatinine and serum uric acid are lower than what is reported as normal range for healthy females. Pregnancy is one of the well- known causes of physiologic low serum uric acid level in females. Clinicians should consider preventive measures to prevent AKI even if the serum creatinine and uric acid is within normal range for the non-pregnant female. Based on the trimester of pregnancy AKI can be classified into three categories as follows: first half, Second half, and Post-partum. AKI can also be categorized as be pre-renal, renal or post-renal [2].

In the first half of pregnancy, the risk of pre-renal oliguria follows an event known as hyperemesis gravidarum. In the first trimester since pregnant patients may have persistent nausea and vomiting resulting in weight loss and ketonuria, they may present with acute incidence of oliguria associated with hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis. The recommendation is to avoid and withhold non-essential drugs such as Iron supplementation that can cause nausea and vomiting. Infusion of dextrose containing fluids which may precipitate Wernicke’s encephalopathy should be avoided. A combination of anti-emetic drugs may be required to ameliorate nausea and vomiting to prevent AKI as a result of dehydration. Usually these cases of AKI in pregnancy are preventable [3]. Acute oliguria in first trimester may be the outcome of unsafe abortion practices by uneducated mid-wives. Infected abortion complicated by fever and endometritis remains the most serious threat to a pregnant women’s health in the developing world [3].

In the second half of pregnancy, the major cause of AKI is preeclampsia, a consequence of a specific renal lesion called glomerular endotheliosis in enlarged ischemic glomeruli. Clinical manifestations are elevated blood pressure (>140/90) after 20 weeks of pregnancy in previously normotensive patients and proteinuria greater than 300mg/24 hours. The main hemodynamic finding is general vasoconstriction and hemoconcentration with reduced intravascular volume. If untreated, up to 5% of pregnant women with preeclampsia develop HELLP Syndrome, defined as a combination of hemolysis with elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count and abnormal RBCs in the peripheral blood smear. Some systemic immunologic diseases such as Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) might increase the incidence of Preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome. Serum from patients with HELLP syndrome exhibits activation of the alternative pathway of complement [4]. Acute Fatty Liver of Pregnancy (AFLP) during the second half of pregnancy usually occur in the third trimester; fatty infiltration of hepatocytes occur in the microvascular system and cause liver failure in pregnant women. AKI develops in 90% of patients with AFLP [5].

Conclusion

In cases of AKI during pregnancy which have different etiologies two aspects are to be considered. Supportive care is important. AKI can be prevented by early recognition and treatment of the underlying cause, for example early treatment of infections and sepsis, early treatment/prevention of dehydration, and ccorrecting hypovolemia and hypervolemia. Review of medications, monitoring use of drugs such as Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatories (NSAIDs) and Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE) inhibitors is paramount, and the lowest possible doses should be used. Treatment of underlying diseases such as high dose corticosteroids in cases of SLE patients is also important.

Considering that the post-partum kidneys are still at risk after delivery, we recommend considering all causes of post-partum AKI, such as puerperal infection, massive hemorrhage, and hemolysis, systemic diseases such as SLE, post-partum preeclampsia, drug induced nephrotoxicity and analgesic nephropathy.

This 29 year old mother had no signs or symptoms of local or systemic infection. There was no sign of bleeding on physical exam or evidence of hemolysis, as evidenced by normal color of skin and mucosa and shape of RBCs on peripheral blood smear. The patient underwent a full immunological laboratory evaluation for SLE and thrombotic microangiopathies. Diagnosis of post-partum preeclampsia was unlikely as a decrease in renal function happened too early with no epigastric pain or convulsions. Finally, in any AKI especially post-partum, physicians should rule out obstruction of the urinary tract as we did in this case via an abdominal and pelvic ultrasonography. We expected some degree of mild dilatation of the urinary tract due to pregnancy which lasts for a few weeks post-delivery. Consuming two types of NSAIDs raised suspicion for a diagnosis of NSAID induced nephropathy [6]. Heavy fluid intake contributed to her edema and hypertension. The patient was advised to stop NSAIDs and drink less. Her blood pressure decreased in two days and peripheral edema subsided. The patient was discharged after four days. Understanding hazards to mothers post-delivery will decrease morbidity and mortality. In Post-partum acute renal failure as in the general population, simple causes may be overlooked, and physicians should be aware of urinary tract obstruction, adverse effects of bad nutrition and harmful drugs as possible etiologies of AKI.

References

- Salim R, Woelfer B, Backos M, Regan L, Jurkovic D (2003) Reproducibility of three-dimentional ultrasound diagnosis of congenital uterine anomalies. Ultrasound Obstetric Gynecol 21(6): 578-582.

- Rao S, Belinda J (2018) Acute kidney injury in pregnancy: The changing landscape for the 21st Kidney International Reports 3(2): 247-257.

- Huang C, Shanying C (2017) Acute kidney injury during pregnancy and puerperium: A retrospective study in a single center. BMC Nephrology 18(1): 146.

- Vaught AJ, Eleni G, Nancy H, Karin B, Xuan Y, et al. (2016) Direct evidence of complement activation in HELLP syndrome: A link to atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Exp Hematol 44(5): 390-398.

- Knight M, Nelson-Piercy C, Kurinczuk JJ, Spark P, Brocklehurst P (2008) A prospective national study of acute fatty liver of pregnancy in the UK. UK Obstetric Surveillance System. Gut 57(7): 951-956.

- Kate SW, Anita B (2016) Acute kidney injury in pregnancy and the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. The Obstetrician & Gynecologist 18(2): 127-135.

© 2022 Behrooz Broumand. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)