- Submissions

Full Text

Perceptions in Reproductive Medicine

Factors Influencing the Spread of Domestic Violence among Heterosexual Marriage in Western Kenya

Silali Gerald MB*

Kenya

*Corresponding author: Silali Gerald MB, Kenya

Submission: April 18, 2019; Published: May 20, 2019

ISSN: 2640-9666Volume3 Issue2

Abstract

Domestic violence in heterosexual partners, remain a major challenge on, Sustainable Development Goals. Globally domestic violence is increasing, with 31% and 69% men and women respectively, being physically, sexually or psychologically, assaulted by their intimates partners, due to variations in: socialcultural, gender isolation in secondary schooling at puberty, thus a missed opportunity in life. The silence conflicts in religions, Beijing resolutions, of 1985 and, African gender roles and power, remain sources of violence in SSA. Neglects of boy child pose serious threats, makes him, more vulnerable to domestic violence. In Kenya, for every 1000 heterosexual households, 3.8 female and 1.3 male succumb to disasters associated with domestic violence per month, due to income variations or poverty index inflation, affluence alcoholism, and hacked brains to internet, and other social platforms. Hence, need to investigate, factors influencing spread of domestic violence, specifically, social cultural, social economic, Neglect of boy child, and in fight of gender roles and power, as sources of domestic, violence. Study was cross sectional descriptive design, in stratified, random, and purposive sampling, using mixed research. Sample size of 267 respondents exploited, Quantitative data was analyzed by descriptive frequency and inference, while qualitative data, by contents analysis, of sub themes.

Results depicted that, 53% of heterosexual intimates between age, from same social cultural and traditional values, had a stronger and mutual married bond, than, 47% of integrated traditional and cultural values. Social economic status, in fighting of gender roles and power influenced negatively, on gender equality, with 95% CI 4.3, P=2.46. Majority 64% of female intimates, on high income influenced, domestic violence, resulting single parenting, then those from low income, small scale farmers, with disaster risks of OD, [2.3, 0.6]. Misuse of social platforms and internet, had positive significant, leading to neglect of marriage roles, especially cooking and serving of meals, among female gender, ‘‘male are supposed to be served by their wives, not their maids, as per African culture and value of marriage ’’, thus social genocide, if maids serve men in presence of their wives. The neglect of boy child was attributed with, over 80% domestic violence, as noted from lack of boys’ issues, documentations, from all government policies guidelines, or NGOs’ advocate, to promote boy child, as a future role model. Alcoholism among intimate couples influenced negatively, a cross genders, as a psychological shock absorber and defensive mechanism, related disasters of violence. Even though, the effects of alcohol remain silent among, highly income households, often goes viral, among low-income households. Cry, could be heard, carrying green twigs, as sign of peace, ‘‘we want our conjugal rites from ever drunkard males” The study also opined that, modern gender roles and power in marriages, has negative significant, on heterosexual marriages, which has resulted to separation, and divorce from female of higher salaries, than their husbands. Need for mutual partnership in uptake gender, roles and power, in context of African cultural values, and rites, to empower and sustain, Beijing resolutions of 1985, comprehensively and holistically.

Abbreviations:Domestic violence; Boy child neglect; Alcoholism; Social cultural; Social economic; Gender roles and power in family; Rites and traditions

Introduction

Domestic violence in heterosexual marriage remains a major rising intimate social challenge with distinct unique features in various family households [1-3]. There is need for integrated appropriate traditional contexts of different values and norms to control and prevent recurrent collision of modern gender equality regime policies [4]. This is in part due to the complex interplay between gender and children relationships in the modern societies of rising tides, gender equality and cultural change [5]. Domestic violence remains a global obstacle , and a family disaster in achievement of sustainable development goals of vision 2030, that need health prevention [6], on ending poverty in all its forms, to end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture, to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages, Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote life-long learning opportunities for all in both developed and developing countries, [7]. Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all, Promote peaceful and inclusive family households and societies for sustainable development as opined in 2014.

Domestic violence against gender, committed within the homestead, may be physical, sexual and psychological abuse, as well as neglect of one gender, whose impact, affect children at large [8]. In Kenya, for every 1000 heterosexual intimate households, 3.8 female and 1.3 male become victims of domestic violence per month attributed to poverty, affluent to alcoholism and drunkenness, or minds being married to internet], and other social platforms, and misuse of biological gender power, by well off females or males to enhance domestic violence. A severe and escalating form of domestic violence is majorly characterized by multiple forms of abuse, terrorization and threats, and increasingly possessive and controlling behavior on the part of the abuser [9]. Moderate form of domestic violence where continuous frustration and anger occasionally erupt into physical aggression common to rural women [10] hinders them from participating in family decision making [11-13]. Heterosexual marriage accounts for a significant number of morbidities and mortalities and hinders woman globalization in rural community due to various murder related to gender inequalities such as suicide, among women [14] or homicide common in inmate men of low income than women [15], on long term intimate challenges, therefore rich women look for space and state for power in the household, through the murder of her husband [16,17] rather than legal divorce or separation, since she is economically stable and can silently sponsor for that very crime to happen in the family behind, the consciousness of her intimate partner [1,5]. Alcoholism is a chronic disease in both genders, may be a sole value to hide an intimate challenge [18] that may influence domestic violence, is a primary disorder and not a symptom of other diseases or emotional problems, chemistry of alcohol allows it to affect nearly every type of cell in the body, including those in the central nervous system for normal consciousness. Effects of alcoholism need early prevention, through health education and health promotion to enhance harmony in the marriage and woman partnership national developments and policy making [8,17].

Research studies across integrated cultures have come up with a number of social cultural variations due to community intermarriage that might give rise to higher levels of domestic violence, if intimate partners cannot understand one another in term the appropriate technology of marriage, in line with their tradition rites and values [5]. Socioeconomic variables may determine domestic violence in varying grades of poverty, wealth and health, among different scales of women and men labor force, finance participation, education, reproduction and infertility challenges [12]. It has been suggested that the level of genderequality is positively correlated to a country’s development [19- 21]. Children are often present during domestic exchanges and violence, a study in Ireland opined that, 64% of abused women and, their children routinely witnessed the violence, as did 50% of abused women in Monterrey, Mexico. Children who witness marital violence are at a higher risk for a whole range of emotional and behavioral problems, including anxiety, depression, poor school performance, low self-esteem, disobedience, nightmares and physical health complaints [22-25]. Features of the neglected boy child ‘made invisible’ grows up to be a bigger danger to society than girls, and so needs to be taken care of and made conscious of the patriarchy and how better to channel aggression and anger among boys [21]. In a world that is deeply misogynistic and leaves the black girl child in a more vulnerable position, how do we navigate the social challenges like that of poverty, lack of educational access and abuse without physically and socially ignoring boys? [18].

Murder of intimate male or females as source of domestic violence

Globally and in sub Saharan Africa, data from a wide range of countries suggest that intimate violence among heterosexual marriage accounts for a significant number of morbidities and mortalities , and hinders globalization of rural women [15], such as suicide murder among women [3] or homicide murder in men organized by rich women [7], due to persistence violence, therefore rich women look for space and state for power in the household, through murder of her husband [7] rather than legal divorce or separation, since she is economically stable and can silently sponsor for the very crime to happen in the family behind, consciousness of her intimate partner [5]. such incidence is common in urban set up and in rich business women in Kenya, who end up being single parents [16] and are against the global agenda on Beijing conference for women and globalization [15], politics, power and economic ideas [17].

Majority of male married to females of higher income commits homicides and easily seek legal divorce, due to prolonged gender in quality income, and growth [11], while female low or no income or small scale farmers, commits suicides due to intimate difference, political powers and economic constrains in family, and high level of poverty at nuclear family [17], Studies from Australia, Canada, Israel, South Africa and the United States of America show that 40- 70% of female murder victims were killed by their husbands or boyfriends, frequently due to the domestic violence [14]. Although we have a good data on prevailing homicides and suicide cases [9], from other parts of the world, the impact of domestic violence on suicide and homicide crimes, remains a big challenge in mitigating domestic violence in modern society. In sociocentric societies where shame is a more prevalent emotion, the victims of domestic violence may not open up about their trauma and hence may not report it. This not only affects the victim negatively but also affects an understanding of the true nature of trauma and rates of these acts, thereby influencing policymaking. In sociocentric cultures, relations between people are at the core and individual identity is subsumed in the family or kinship, Victims of domestic violence face the danger of suffering negative reactions upon disclosing their trauma, the most traumatizing of which includes being blamed for the assault. Studies have indicated a relationship between high levels of gender prejudice and stereotyping and high levels of victim blame [26-28].

In Kenya and western Kenya intimate related murder cases, as a source of domestic violence, continue to remain silence in rural and urban communities [16] due to, limited accessibility of media advocacy, corruption in security arms, poor witness protection measures in place, and presence of limited accessibility of health information on equity gender economic empowerment and participation [29], and political empowerment, gender equality information [20], in communities always land on many ears, of persistently strong traditional values encroached communities that resist to new gender policies [20]. Though observation surveys and interviews from various chiefs offices and Barazas indicate to have rampant domestic violence, that remain silence due to existing bonds of traditional norms, rites and values in marriage, such kind of information usually reach their office via [nyumba kumi], ‘‘ten house initiative’’ and community policing approaches [25]. Prolonged limited access to research and advocacy against violence in rural and urban communities on [13], matters of family planning sexual and infertility [30], remains to be an abomination in some religions, African traditions, cultures and norms. Communities with such stringed cultural values, still do not allow women to stand before men to address, in some communities they could be allowed to do so while on knees, [28] and have not accepted the global gender equality regime or Beijing resolution of 1985, in the society [23], thus we realize persistence domestic violence, where men still fight for space of headship of the household even if he is married with rich women, or the women has a lot of economic power than him which remain the ignition of domestic violence [19,22], and major obstacle towards the implementation of the emerging global gender and equality and gradual to enhance quality cultural change [20,23].

Alcoholism and drunkardness, in heterosexual marriage as source of domestic violence

Alcoholism is a chronic disease in both genders, may be a sole value to hide an intimate challenge [18] that may influence domestic violence, is a primary disorder and not a symptom of other diseases or emotional problems, chemistry of alcohol allows it to affect nearly every type of cell in the body, including those in the central nervous system [18]. In brain, alcohol interacts with centers responsible for love pleasure and other desirable sensations [29]. After prolonged exposure to alcohol, the brain adapts to the change’s alcohol makes and becomes dependent on thus, drinking becomes the primary medium through which they can deal with intimate partner, work, and marriage life. It dominates intimate partners thinking, emotions, and actions against global gender equality in the family to cause divorce or separation [23]. The severity of this disease is influenced by factors such as genetics, psychology, sexual, abuse by either intimate partner, variation in culture, or response to physical pain in the family [30,31]. Studies indicate that in a single year, between 3.4% female and 9.7% male in a heterosexual marriage are dependent on alcohol which remain a hidden health challenge in marriage [18], and domestic violence.

In one of the studies, we opined that 15% of men and 12% of women over age 60 drank more than the national standard for excess alcohol consumption to hide the figure of their culture [32]. Most alcoholics in Sub Saharan Africa are men, but the incidence of alcoholism in women has been increasing over the past 30 years. About 9.3% of men and 1.9% of women are heavy drinkers, and 22.8% of men are binge drinkers compared to 8.7% of women. In general, young women problem drinkers follow the drinking patterns of their partners, although they tend to engage in heavier drinking during the premenstrual period [30], which remain a health that is hidden, [33]. Women tend to become alcoholic later in life than men, and it is estimated that 1.8 million older women suffer from alcohol addiction [34]. Even though heavy drinking in women usually occurs later in life, the medical problems women develop because of the disorder occur at about 21, the same age as men, suggesting that women are more susceptible to the physical toxicity of alcohol and domestic violence [30]. Severely depressed or anxious intimate partners are at high risk for alcoholism, smoking, and other forms of addiction that affect mostly women and children in rural communities [30]. Then happy flourishing marriage, Major depression, in fact, accompanies about one-third of all cases of alcoholism influence patriarchal terrorism and couple violence [21]. It is more common among alcoholic women than men.

Depression and anxiety may play a major role in the development of domestic violence and act as source of hidden health problem that needs brain storming [18]. Research suggests that for women, the most serious risk factor for injury from domestic violence may be a history of alcohol abuse in her male partner [16]. Alcoholism in parents also increases the risk for violent behavior and abuse toward their children, who tend to do worse academically than others, have a higher incidence of depression, anxiety, and stress and lower self-esteem than their peers Alcoholic households are less cohesive, have more conflicts, and their members are less independent and expressive than households with nonalcoholic or recovering alcoholic parents. In addition to their own inherited risk for later alcoholism, one study found that 41% of children of alcoholics have serious coping problems that may be lifelong. Adult children of alcoholic parents are at higher risk for divorce and for psychiatric symptoms. Researchers believe that alcohol operates as a situational factor, increasing the likelihood of violence by reducing inhibitions, clouding judgments and impairing an individual’s ability to interpret cues. Excessive drinking may also increase partner violence by providing ready fodder for arguments between couples [21]. Others argue that the link between violence and alcohol is culturally dependent, and exists only in settings where the collective expectation is that drinking causes or excuses certain behaviors. In South Africa, for example, men speak of using alcohol in a premeditated way to gain the courage to give their partners the beatings they feel are socially expected of them. Despite conflicting opinions about the causal role played by alcohol abuse, the evidence is that women who live with heavy drinkers run a far greater risk of physical partner violence, and that men who have been drinking inflict more serious violence at the time of an assault, and these remain untold and undocumented in western Kenya.

Social cultural factors as source of domestic violence

An individual of today is shaped by the culture that he or she is born in and lives through, acquiring cultural values, attitudes, and behaviors [24]. Culture determines definitions and descriptions of normality and psychopathology. Culture plays an important role in how certain populations and societies view, perceive, and process sexual acts as well as domestic violence [8,12]. Cultural variations in gender roles and permitted gender behaviors may play an important role in cases of domestic violence by men from one culture on women from a different culture. Sexual bargaining is a social process by which potential partners communicate interest/ disinterest in pursuing a sexual relationship with each other [8,17]. Research studies across on integrated cultures have come up with a number of social cultural variations due to community intermarriage [1,23] which might give rise to domestic violence, if intimate partners cannot understand one another in term the appropriate technology of their tradition cultures, rites and values in marriage [1,22]. Levinson’s analysis suggests that wife beating occurs more often in societies in which men have higher economic income and decision-making power in the household, where women do not have easy access to divorce, and the second strongest predictor in this study of the frequency of wife beating was the absence of all-women work groups [2,8]. Advance of this hypothesis that the presence of female work groups offers protection from wife beating because they provide women with a stable source of social support as well as economic independence from their husbands and families [8]. It has been argued, for example, in an intimate domestic violence is more common in places where war or other conflicts or social upheavals are taking place or have recently taken place hindering growth of the family and development [6].

Paternalistic cultural models encourage the view that men protect women from harm, thus giving the impression that women are largely incapable of protecting themselves [2], traditional gender-specific socialization and cultural norms, including values that give men proprietary rights over women, notions of the family as private and under male control, customs of marriage and the acceptance and glorification of violence, as a means to resolve conflicts, make violence against women culturally acceptable [9,11]. Women’s economic dependence on men, due to women’s limited access to employment, cash and credit, and because of discriminatory laws regarding inheritance and property rights, is another factor promoting thought to be domestic violence against women [13]. Legal discrimination against women, for example regarding divorce, child custody, maintenance and inheritance, as well as legal definitions of rape and domestic abuse, increase the likelihood of violence against women [20]. Domestic violence has become commonplace among heterosexual partners, and individuals have easy access to weapons, social relations, including the roles of men and women-are frequently disrupted [26]. During these times of economic and social disruption, women are often more independent and take on greater economic responsibility. Whereas men may be less able to fulfill their culturally expected roles as protectors and providers. Such factors may well increase partner violence, but evidence for this remains largely anecdotal, [24]. Others have suggested that structural inequalities between men and women, rigid gender roles and notions of manhood linked to dominance participation of family affairs, male honor and aggression, all serve to increase the risk of domestic violence [25]. Again, although these hypotheses seem reasonable, they remain to be approved by firm cultural and traditional evidence realized in some parts of western Kenya [19].

Social economic as source of domestic violence

Socioeconomic variables may determine domestic violence in varying grades of poverty, wealth and health, among different scales of women and men labor force, finance participation, education, reproduction and infertility challenges [20,27,29]. It has been suggested that the level of gender-equality is positively correlated to a country’s development [23,31]. This argument is rooted in social modernization theory, which suggest that in countries with high level of economic development, basic needs have been satisfied, and thus, more emphasis can be put on social and cultural concerns on new culture of gender equality implementation in synergistic partnership in context to traditional cultures and rites, so that they become sustainable, [27] by both gender in our society, and reduce prevalence of domestic violence [4,25,27]. Following a similar argument, that economic development leads to “attitudinal changes in perceptions of the appropriate role technology of women” [20]. The need research in gender violence and family planning [13,14], as far as woman globalization is concerned to influence its sustainability [15]. Furthermore, the wealth of a country may also influence the extent to which it promotes gender equality, by providing necessary financial and technical resource assistance to programs that benefit both men and women equitably [19].

Gender equality programs are made possible because the country is able to provide the necessary financial support for such programs, however studies in Sub Saharan Africa indicates efficient wealth obtained from such programs, in majority of heterosexual partners is being abused to facilitate, divorce, intimate separation, suicide, homicides and other related domestic violence [7,14]. Alcoholism as a hidden culture figure and more prevalent in people with lower educational levels and low or no income at all [28]. Prevalence of alcoholism among adult gender is 4.3% to 8.2%, in western Kenya, which is less comparable to the 7.4% found in the general population, there was also no difference in prevalence between poor African Americans and poor whites. People in low income groups did display some tendencies that differed from the general population [18]. Both genders are at risks of being heavy drinkers. It depends on various prevailing environmental risk factors surrounding the specific individuals. Excessive drinking may be more dangerous in lower income groups; one study found that it was a major factor in the higher death rate of people, particularly men, in lower socioeconomic groups compared with those in higher groups [2]. While observation studies in Kenya established that, females of higher income and (bread winners) decision-making in roles and power to men, have a high relative risk of divorce or separation, due to prolonged communication breakdown, on gender equality and traditional culture conflicts [8]. Besides, human costs, domestic violence places an enormous economic burden on the immediate community in terms of lost productivity [30], psychological torture of children, and increased use of social services [30]. Among women in a survey in India, for example, 13% had to forgo paid work, because of abuse, missing an average of 7 workdays per incident, and 11% had been unable to perform household duties because of an incident of domestic violence. Such figure remains undocumented in western Kenya, but observation studies link most affected families and children with violence with drug abuse and terrorists in the society. Although partner affected by domestic violence does not consistently affect a woman’s overall probability of being employed, it does appear to influence a woman’s earnings and her ability to maintain a happy family and job [27,31]. A study in Chicago, in United States, found that women with a history of partner violence were more likely to have experienced spells of unemployment, to have had a high turnover of jobs, and to have suffered more of sexual, physical and mental health problems that could affect job and family performance, [27]. They also had lower personal incomes and were significantly more likely to receive welfare assistance than women who did not report a history of partner violence [25].

Similarly, in a study in Managua, Nicaragua, abused women earned 46% less than women who did not report suffering abuse, even after controlling for other factors that could affect earning, however though, such challenges affect the study area, and no data is documented in assistant chiefs’ office but is viral in the public domain. Globalization has helped to chisel away sexist structures, processes, and attitudes leading to an erosion of the sexual division or labor replaced with a more equitable allocation of resources and power within the household” [16,20]. The basic idea underlying this argument is that, if women were afforded the opportunity to earn a living wage, then their dependence on men is lessened, and their bargaining power within the household is increased [4]. A woman’s right to work, the nature of her work that may in one way or another influence domestic violence, showed in an empirical study of 180 countries between 1975, and 2000 that globalization has enhanced gender equality through offering women new opportunities for income-generating work and not enhanced men gender [8]. Taking that perspective, the spread of neoliberal policies, as a result of economic globalization, helped women entering the workforce and facilitated changes regarding traditional gender roles thus influencing the modern domestic violence among heterosexual partners [21].

Domestic violence as source of failure in children quality growth and development

Gender isolation in secondary schooling at puberty, separates girls from boys, which make these learning youth group, miss the future make up of being future good mothers and father, thus a missed opportunity in life on isolated case of domestic violence. Children are often present during domestic exchanges and violence, a study in Ireland opined that 64% of abused women said that, their children routinely witnessed the violence, as did 50% of abused women in Monterrey, Mexico. Children who witness marital violence are at a higher risk for a whole range of emotional and behavioral problems, including anxiety, depression, poor school performance, low self-esteem, disobedience, nightmares and physical health complaints. Which are similar with Kenyan children. Studies from North America indicate that children who witness violence between their parents frequently exhibit many of the same behavioral and psychological disturbances also like the affected parents [24]. Domestic violence may also directly or indirectly affect child mortality via suicide or homicide murder in urban centers [16,18], in Sub Saharan Africa. Researchers in Leon, Nicaragua, found that after controlling for other possible confounding factors, study in the Indian states of Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh found that women who had been beaten were significantly more likely than nonabused women to have experienced an infant death or pregnancy loss (abortion, miscarriage or stillbirth), even after controlling for well-established predictors of child mortality such as the woman’s age, level of education and the number of previous pregnancies that had resulted in a live birth as a source of violence was also noted positively to be a source of violence in western Kenya.

Community health participation in prevention of domestic violence in the society

Community health interventions are traditionally characterized in terms of three levels of prevention: Primary preventionapproaches that aim to prevent violence before it occurs Secondary prevention – approaches that focus on the more immediate responses to violence, such peace healing and reconciliation, such as health sex in marriage in family [18,29]. Tertiary prevention approaches that focus on long-term care in the wake of violence, such as rehabilitation and reintegration, and attempts to lessen trauma or reduce the long-term disability associated with domestic violence [25,29]. These three levels of prevention are defined by their temporal aspect whether prevention takes place before violence occurs, immediately afterwards or over the longer term [16]. Although traditionally they are applied to victims of violence and within health care settings, secondary and tertiary prevention efforts have also been regarded as having relevance to the perpetrators of violence and applied in judicial settings in response to domestic violence, through health education and promotion [17,29].

Neglect of boy child in up bring of society as source of domestic violence

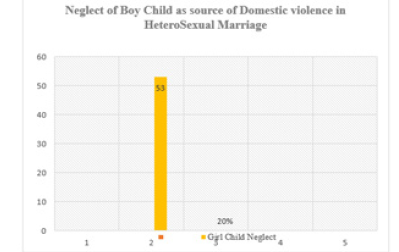

Features of the neglected boy child ‘made invisible’ grows up to be a bigger danger to society than girls, and so needs to be taken care of and made conscious of the patriarchy and how better to channel aggression and anger among boys [21,25]. In a world that is deeply misogynistic and leaves the black girl child in a more vulnerable position, how do we navigate the social challenges like that of poverty, lack of educational access and abuse without physically and socially ignoring boys [18]? Kabel Chabalala is a founders of Young Men Movement which has observed that the boy who has experienced abuse of some form will more likely be subjected to delinquent activities than his female counter part who has experienced almost the same kind of abuse since is a hidden health problem [17,21]. It is for this reason they decided to look into how a boy child’s world is molded by checking the stereotypes around them [22], as distinct violence. Neglected boy child is more dangerous than neglected girl child, hence once the boy child becomes more ignored he becomes even more dangerous to society, we feel so unsafe, so we need to teach him why we want to correct this injustice, that we want to help the girl child be empowered and independent because of the injustice of the past, not just go about it and leave him out, will reappear in marriage period in of domestic violence [20]; (Figure 1). Advocacy for gender equality has become an issue of global concern [24]. Most National governments have incorporated gender equality strategies into their policy programs on favor of girl child than boy child with considering the future placed before them, and gender equality has become an important item on the agendas of international organizations. This has led to the emergence of what [23], has called the global gender equality regime, a series of policies, norms, laws and mechanisms to ensure gender equality and women’s rights on a global scale [16,23]. While gender policies have long been viewed as demands of a marginalized group, they are now central to most government policies [20] Major milestones on gender equality include the “Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women” (CEDAW), which asks states to incorporate policies that support women, hence ignore to discuss on men issues; and the Platform for Action and the Beijing Declaration, which set gender equality as a goal [24]. There is empirical evidence that these recommendations, have helped to improve woman’s rights and gender equality nationally [17] and neglected men right to retain their natural gender equality. According to this causal account, the global diffusion of gender policies is a result of the emergence of global gender equality norms on women. Without dismissing the plight of young women, he said while it is important to pursue equal rights for women through programs like ‘Take a Girl Child to Work’, oftentimes society neglects the young men who make up some of the country’s most vulnerable communities. We need to start empowering women ensuring that they also get to be in those managerial positions.

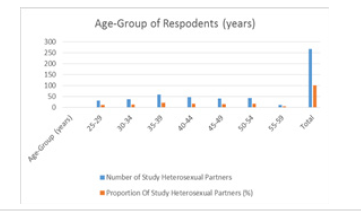

Figure 1:Distribution of Respondents by Ages in complete years.

However in us trying to have that pursuit we are forgetting so much about the boy child, we are not even giving a platform for him to understand from their role models like, this is what happened in the past in marriage life, and this is why we are focused more on the girl child instead of giving you attention to both genders. UN women’s conferences were “lightning rods that have helped to channel the collective buzz of ideas and energy emanating from the global women’s movement into prescriptions for and commitment to policy action at the level of nation states” [30], thus Neglecting child boy. UN conferences also promoted the growth of the global women’s movement. This movement made sure that gender issues were also incorporated in the agenda of other UN conferences, such as the 1993 World Conference on Human Rights, the 1994, Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, the 1995 International Conference on Population and Development and the 1995 World Summit for Social Development [27]. Taking this perspective, globalization presents a window of opportunity for the diffusion gender policy reforms among women and neglect child boy which could be root cause of domestic violence in our society [26].

National policies to combat violence against women include government sponsored support programs for victims of violence, which provide training and professional counseling, shelters and emergency housing for battered women and not men, crisis centers, public education initiatives and national laws [25]. In Latin America, national laws are the most common measure adopted by governments to curb violence against women. Most of these laws tackle the issue of domestic violence and frame the issue as a family issue. This point is further discussed in chapter four Why do governments adopt policies to combat violence against women and what accounts for cross-country variations regarding the adoption of policies on violence against women [31]. The existing literature identifies domestic structures and actors as reason for the introduction of national policies to combat domestic violence and as an explanation for cross-country differences, including the domestic women’s movement, [17] social and economic rights, cultural differences [19]. A more recent body of Literature highlights the importance of epistemic communities and the world society in promoting national policies on violence against women, building empirically on evidence from single country studies, as well as from regional or global research [14]. These studies trace the introduction of national policies on violence against women back to the existence of international norms and international networks. Overall, the literature on violence against women points out that a combination of national- and international-level factors are responsible for the diffusion of policies on this issue [19]. In particular, epistemic communities and the international networking of woman’s rights organizations, as well as international norms, are identified as important reasons for the national introduction of measures on violence against women [23].

Role of gender power and as source of domestic violence

Domestic violence among heterosexual partners is very much related with gender inequity, as it assumes that women suffer because of their subordinate social status in relation to men [12]. It assumes that the roots cause of violence against women are located in historical unequal power relations and jealousy for love and sex between men and women, [8]. The difference between this kind of violence and other forms of aggression and coercion is that the risk or vulnerability factor is simply being female [3,20]. Thus, laws dealing with violence against women can be regarded as gender equality laws. The issue of violence against women includes, generally speaking, aggression and rape, sexual harassment at work, abuse of women belonging to ethnic minorities, trafficking of women, prostitution, pornography, violence in the media, and physical, sexual and psychological abuse in the home by partners or spouses [25,28,32]. Gender equality is an ideal condition in which all men and -all women have similar opportunities, to participate in politics, the economy [1] and social activities; their roles and status are equally valued; neither suffers from gender-based disadvantage or discrimination; and both are considered free and autonomous beings with dignity and rights” [1,2].

Gender equality policies are rooted in many policy areas, including family law and social welfare policy, gender policies are measures through which governments move toward the ideal of gender equality between male and female like in Kenya, government advocates for current one third gender female in any government power job, or service. Research from Mazur defines gender policies to include eight sub sectors: blueprint policies, political representation, equal employment, reconciliation, family law, reproductive rights, sexuality and violence and public service delivery [10,12] which remains silence or neglected in boy child. Blueprint policies consist of constitutional provisions, legislation equality plans, reports and policy machineries governments use to establish general principles or a blueprint for feminist state action at the national and sub-national level, neglecting masculine state, [12,26].

Policies regarding political representation aim to establish gender parity in political decision-making and neglect its role, in intimate marriage which is biological in nature and core role in procreation of life is concerned. Equal employment policies are concerned with gender balance in the workforce [19,25]. Not in procreation duties, which is forgotten only to submerge as a domestic violence. Reconciliation policies aim to resolve gender issue during war and in a post-conflict context [5]. Gender policy reforms of family law establish equality between men and women regarding family issues. Reproductive rights and policies on sexuality and domestic violence focus [13], on the bodily integrity of women and not man why? Policies targeting public service delivery tackle gender impunity regarding social services [18]. Some of these policies are aimed at all women or all citizens, whereby others primarily target marginalized or under-privileged sub-groups [12]. Proponents of neo-classical economic theory hold that economic globalization accelerates economic development, and thereby positive spill-over effects will improve both men and women’s future life as intimate partners not to enhance domestic violence [20]. Neoclassical theory holds that the elimination of barriers to trade and capital stimulates competition and economic growth and enhances the life of all citizens by raising income standards as well as by improving educational opportunities for all members of society [8,22]. There is some empirical evidence for the assertion that the implementation of free-market policies is strongly associated with economic growth and a reduction in income inequality [11,19]. There is further empirical evidence supporting the argument that globalization, by promoting economic development, offers many ways in which women can exercise and improve their agency [6]. For example, economic growth should help facilitate higher government expenditure on programs and measures supporting woman’s rights [15]. In addition, it has been argued that globalization ‘‘has helped to chisel away sexist structures, processes, and attitudes leading to an erosion of the sexual division or labor replaced with a more equitable allocation of resources and power within the household. The basic idea underlying this argument is that if women were afforded the opportunity to earn a living wage, then their dependence on men is lessened, and their bargaining power within the household is increased. A woman’s right to work, the nature of her work, [12] amount of her wages, and conditions under which she works are increasingly determined by international forces; and access to paid employment through participation in the formal sector and control over income in large part determines woman’s empowerment showed in an empirical study of 180 countries between 1975 and 2000 that globalization has enhanced gender equality through offering women new opportunities for income-generating work [16].

Methodology

Study design

Cross-sectional study design in mixed research of quantitative and qualitative methods of data collection on sources of factors influencing spread of domestic violence.

Study population

The study population consisted of both married urban and rural men and women of reproductive age between 25-50 years who had lived in intimate partners for more than four years and above two years in heterosexual partnership.

Sampling design and sample size

Cluster sampling was used to identify study participants who were in heterosexual intimates, in 6 counties, purposeful selected in the study area, namely Trans Nzio, Uashin Gishu, Kakamega, Bungoma, Migori, Homa bay and Vihiga with a total of 300 study participants. A register from assistant chief’s office was used. This method ensured equal representation of participants in each cluster. This procedure was convenient since each cluster registered had equal chance of being included in the study.

Selection of study units

Village elders were used as reference points to identify targeted households around it and selecting the first household with nuclear family for the last three years, while enumerators carried out data collection in the households identified by village elders. The first household for enumeration was selected randomly. Selection of the second household from the first household was done systematically depending on the number of households identified with the study nuclear family in a cluster (catchment area). Only a man and woman of intimate relation was enumerated per household. For polygamous family, subjects meeting the inclusion criteria were also enumerated.

Inclusion/Exclusion criteria

The primary target for the study were men and women of heterosexual relationships aged between 25 and 59 years at the time of the study. In order to be eligible for this research, both men and women had to be residents of six counties of each specific sub location, had either a nuclear or polygamous family with children, have lived in the area for at least 6 years and most importantly they had to voluntarily accept participation in the research after being taken through the terms and conditions of the research.

Data collection methods and instruments

Quantitative data was obtained using questionnaires from intimate men, women of heterosexual marriage and only their offspring of 18 years and above. The questionnaire was designed to collect information on demographic factors, socio economic, cultural factors and sources of domestic violence in western Kenya.

Focus group discussion was used to collect qualitative data from men, women and children in the households, while Key Informant interview was used to collect qualitative data from the in charge of sub location and village elders in the area. FGD and KII were held validate the quantitative data and answer questions why and how.

Recruitment and training of research assistants

Three focus group discussion moderators and note takers were selected from civil administration and 10 enumerators who were form four leavers and some are doing community policing course in the sub location were selected from the area to participate in household survey and interview. The research team were people with experience in research procedures and knowledgeable of the local language, English and the study sub location. A pretest and amendment were done just before going to the field. Training included briefing on research process principles and ethics and data collection tools.

Data collection

Pilot test was administered on the questionnaire to ascertain the flow of the questionnaire, understanding of the tool and administer the questionnaire test capability of enumerators and determine time taken to administer the tool. Quantitative data was collected for 12 days. The data collection team comprising of 12 enumerators met every day for briefing before the exercise on serializing the questionnaire and supervision of data collection was undertaken and cleaned at the end of each day. Closed ended structured questionnaire was used. The questionnaire was divided into sections as per the study objectives.

Data processing and analysis

Data was entered and electronically analyzed with the use of statistical package for Social Scientist (SPSS) package version 16. Frequencies were used to determine the occurrences and distribution of the variables under study. Cross tabulations were used to determine the level of relationship of the variables that would correlate with each other. In order to ensure correct entry and analysis, cleaning was done from right immediately in the field and during running frequencies to identify wrong data entries and possible omissions. Prompt correction was done immediately such errors were detected. Descriptive analysis was used to examine variables according to the study objectives using Bars, charts, tables, frequencies, percentages and graphs. First cross tabulations were used to find out the patterns in data, this was followed by determining significance of the relationship using chi square test. Statistical tests of significance and validity were used to determine the level at which the study techniques and findings are within the expected standards. A report was then finally written to give detailed and complete account of the whole process. Feedback was given to all relevant authorities and those who were interested with the study findings.

Ethical considerations

Before undertaking the study, the proposal was defended before the County commissioner of Trans Nzioa, County research panel for critic and approval who gave out their recommendation which were included in the study. Consent was then sought from research and ethics committee for its implementation by filling in the ethics form and observing all the requirements on safety and rights of the respondents.

Finding and results

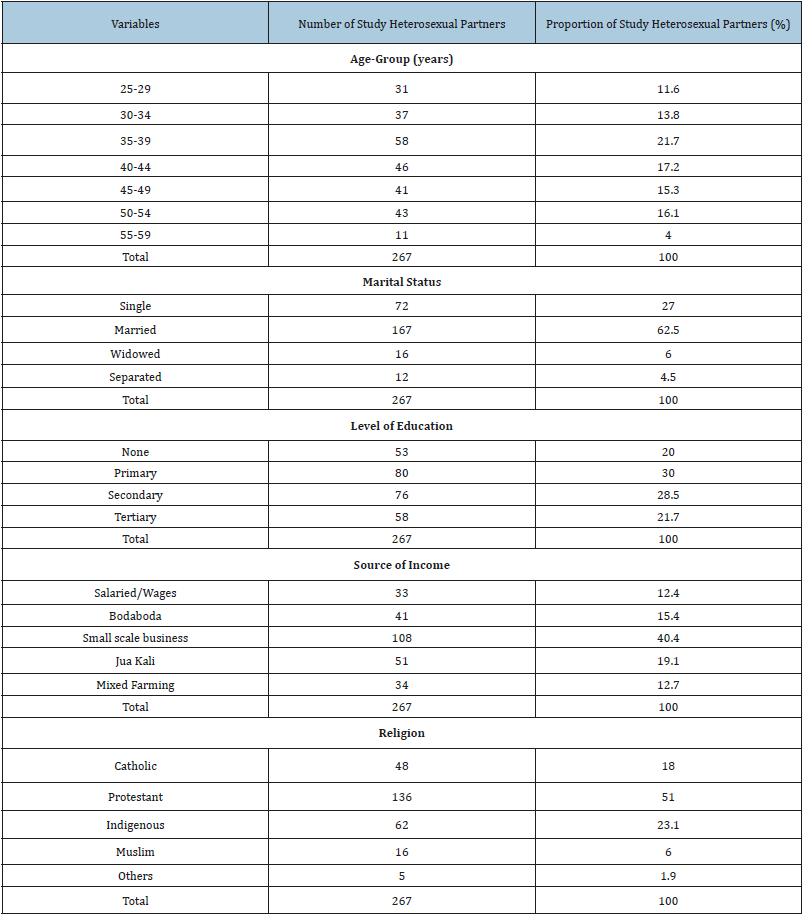

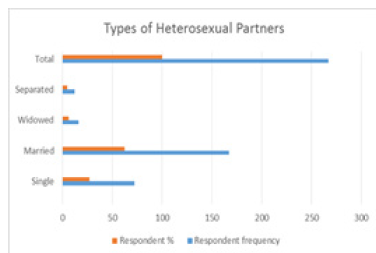

(Table 1) above presents the characteristics of the 267 heterosexual partners who accepted to be interviewed majority (22%) were of age group 35-39 years, followed by intimate aged 40-44 at (17%) a few (4%) were aged 55-59 years old. Among the respondents most (62.5%) of them were married, (27%) of the respondents were single and few (4.5%) were separated. Looking at the level of education among heterosexual partners interviewed, majority (30 %) were primary school leavers, (28.5%) were secondary school leavers while, (21.5%) went up to tertiary level. Considering the source of income of the respondents, majority (40.4%) of the respondents were small scale business, followed by (19.1%) who are in jua kali sector and few (12.4%) are salaried. In religion most (51.0%) respondents were Protestants, (23.1%) belonged to indigenous, and few (18.0%) were Catholics while only (6.0%) Muslims (Figure 2).

Table 1:Demographic characteristics of intimate heterosexual partners.

Figure 2:Showing distribution of the types of heterosexual partners in Western Kenya.

Demographic factors influencing domestic violence

Main sources of risk factors influencing domestic violence were heterosexual men and women gender, aged [25-44], years (64.4%), compare less (35.6%) elderly men and women aged between 45 and 59 years with low level of education. However significant relation exists, between sources of domestic violence, and the aging in heterosexual partners (P value 0.01 95% CI 0.45, 0.86).

Main sources of domestic violence from local administration

Assistant chiefs and village elders, were asked about impact of domestic violence in their sub location and how they were prevented for instance, social cultural factors, social economics, roles of gender among intimate and neglect of boy child in their location, most assistant chiefs (66.7%) have solved many domestic violence related to gender roles especially from females of good salaries, whereby some cases had been resolved in court as violation against women rights, without consideration of male neglect in in our society with relative significance (P value 0.2 95% CI 1.3, 3.7). Some rich women earning more salaries than their husbands do not on recognize their head of the family as written in the bible on matrimonial sacrament. FGD discussants in Trans Nzioa, Kakamega and Homa Bay counties, 24th of June 2018.

Influence of socio-economic cohort strata on domestic violence in society

When asked to mention the main cohort strata with source of efficient and reliable domestic violence from the community were most (52.9 %) were heterosexual intimates aged 30-34 followed by 35-39, (34.9%), integrated cultural values, least cohort affected with domestic violence are heterosexual marriage aged 55-59 years in same social cultural context. Women and men couple aged 55-59 and 50-55 as mentioned by local administration were main source of domestic violence prevention and reconciliation cohort in rural areas, that provide Primary prevention approaches that aim to prevent domestic violence among heterosexual partners, before it occurs Secondary prevention approaches that focus on the more immediate responses to violence, such peace healing and reconciliation, such as health sex in marriage in family. Tertiary prevention approaches that focus on long-term care in the wake of violence, such as rehabilitation and reintegration of both parents, and attempts to lessen trauma or reduce the long-term disability associated with domestic violence with statistical significantly (P value 0.02 95%, CI 1.3,1.4) (Figure 3).

Figure 3:

Association of higher education achieved and domestic violence

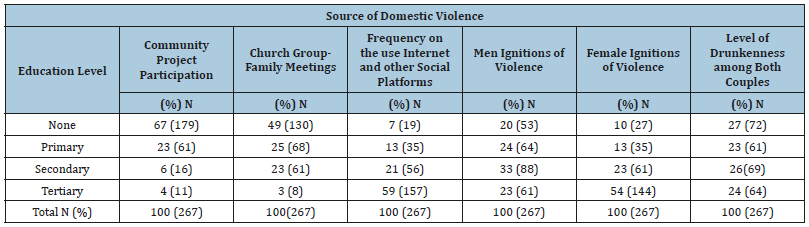

A. Level of education: From (Table 2) Female respondents who went to school up to secondary and tertiary level, are employed or doing booming business, in an integrated cultural marriage and rites, intimate relationships have risk of influencing more domestic violence at (59.0%) and (54.0%) respectively than their counter parts of primary and none education level at (33%) and (24.0 %) respectively. Level of tertiary education statistically significantly influenced domesticated violence that could result to divorce and permanent separation in nuclear families. Relationship between source of violence domesticated in nuclear families due to the utilization of internet and other social platforms in highly educated heterosexual partners were significant especially in couples who got married after achieving education compared to couple who achieved higher education, while in nuclear family and care, with (95% CI 6.9, 2.1).

Table 2:Level of education and source of domestic violence.

B. Accessibility to stable source of income and roles of gender values in society: Source of income was significantly influential in determining source of Domestic violence among heterosexual partners, earning different grades of salary. In this study most (50.0%) of the respondents in western Kenya preferred to partner with families practicing small scale business who closely to in peace and harmony with their intimate partners than where both salaried intimate partners co- exist with ever bedroom violence and disharmony. Irrespective of the various sources of domestic violence, income and poverty, remain the main source of domestic violence for the respondents, Source of income positively influenced domestic violence significantly with, (P value 0.46, 95% CI 0.52, 0.94).

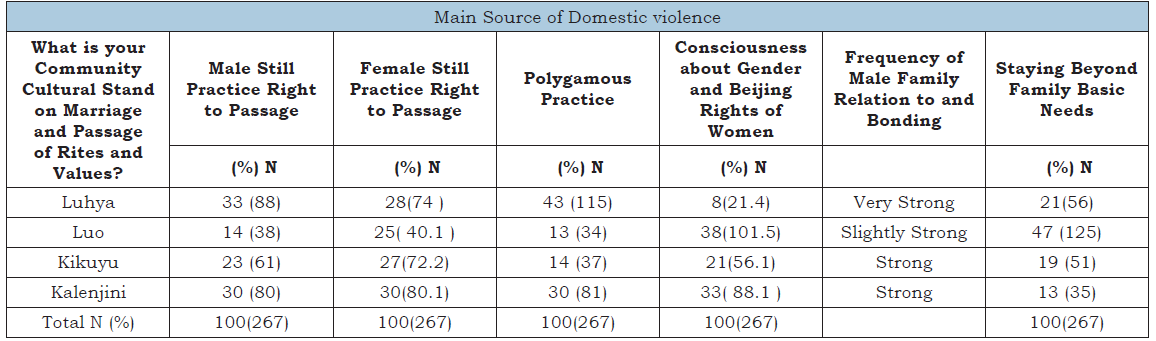

Table 3:Social cultural practices on domestic violence.

C. Social cultural practices on domestic violence: Results from (Table 3) show, most communities which have strong bonds on the family relation in heterosexual marriages such Luhyas and Kalenjins, preferred resolving their family conflict through a family extension in polygamous, for instance in case of infertility, in 43% and 30% cases respectively, the communities also still practice the right to passage in 33% and 30% respondents survey respectively How such communities seem to have silence practices on the Beijing resolution of 1985 on female gender equality policies with significance influence on study of in. (P value 0.01, 95% CI 0.01,0.02). ‘‘Our traditional cultural rites of the rite of passage are biblical and beliefs that when GOD created Man in his image he made him to sleep and took one of his left rib to make him the HELPER who is the women, so Man will remain the head of family, and we do not belief in any resolution of Beijing conference resolutions in 1985, which is against our African culture, and could much be the main challenge on the prevention and mitigation of the increasing domestic violence in the modern societies that required synergistic partnership in appropriate African technology in order to be realized comprehensively and holistically for gender equality and values. ’’KII interviews and FGD discussants. Uasin Gishu, Trans Nzioa, Kakamega and Bungoma counties, 20th,23rd, and, 27th of June 2018. KII with Assist Chiefs and Senior Village elder from same counties for triangulation values.

D. Neglect of boy child as source of domestic violence: Findings from this studies indicate that, over 80% (214) of respondents opined that, majority of government policies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) implementation, on gender equality, prudently advocate for girl child growth and development, and neglect the boy child. While 20% respondents said that policies and NGos implementations, also favors boy child growth and development. Persistence, boy child Neglect in growth and development has limited him to be exposed to less or no role models as a future good father, rendering him to a vulnerable relationship with his community and society, as s source of domestic violence specifically in a heterosexual relationship with these informed girls. Negative gender relation is significant with relative risk of (RR, 2.3), among young couples. Boy neglect is social genocide to African passage of rites and values, thus why, the boy child neglect will remain the silence source of domestic violence, in our community, and as far as gender equality or violence against women is concerned. FGD discussants in Trans Nzioa, Uasin Gishu and Bungoma, 24th of June 2018.

Discussion

Findings from this study indicate a limited utilization of social economic values and cultural rites based on the renowned African contexts, when implementing Beijing resolutions of 1985, on gender equality, it also demonstrate a marked positive significances of Boy child neglect on rights for quality growth and development, as a future major challenges in the fight against domestic violence among the heterosexual marriages , this is of contrast with studies by, Gray & Sandholtzs [16] Hall [19], Ingeharts & Baker [23] that emphasis the need to uphold, the rising tides, gender equality on vital roles of emerging global gender equality, and women globalization on political power of economic ideas like men counterparts. Interestingly in a survey carried out by Levinson’s, suggests that wife beating occurs more often in societies in which men have higher economic income and decision-making power in the household, in in line with study with Heise [20], on defining coercion and consent cross cultural intimates, where women or men, do not have easy access to divorce, and this is a contrast to findings of this study which found out that, women beaten in young couple was a sign of passing over the kitchen to the new couple based on their cultural contest.

Results opined that, majority on female gender on high salaries have positively influence roles of gender and power in marriage, hence, such women have become matriarchal bread winners, which is one of the risk factors, for domestic violence, This is in the agreement with a study by Abramowitz [3] on catching up and forging a head, and Anderson et al. [1], on cross cultural perspective on intimate partner, as a risk factors for domestic, violence. The results are also similar to a study by, Dollar & Gatti [13], on gender inequality income and growth like violence and health, reported by WHO in Geneva 2002). Which demonstrate how gender inequality influence domestic violence. Also this studies discovered that, majority of government policies and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), have continued to neglect on issues of boy child in favor of girl child, hence boy child has become more vulnerable to the society , a study in line with, study by Kabelo Chabalala a founders of Young Men Movement, which has observed that the boy who has experienced abuse of rights in some forms, will more likely be subjected to delinquent activities than his female counter part who has experienced almost the same kind of abuse since is a hidden burden, in their future patriarchal and matriarchal life. Similar study with Johnson & Heise [24,25].

Conclusion

The main sources of domestic violence in the heterosexual marriages, are the main links of the Primary prevention of domestic violence planned and mitigated in the contest of African traditional rites and cultural values. Socio economic factors, like level of education and source of income, boy child neglect in our society, strongly influences the uptake of domestic violence in our communities and society.

References

- Anderson JE, Abraham M, Bruessow M, Coleman RD, McCarthy KC, et al. (2008) Cross-cultural perspectives on intimate partner violence. JAAPA 21: 36-44.

- Apodaca C (1998) Measuring woman’s economic and social rights achievement. Human Rights Quarterly 20(1): 139-172.

- Abramowitz M (1986) Catching up, forging ahead, and falling behind. Journal of Economic History 46(2): 385-406.

- Bailey JE (1997) Risk factors for violent death of women at home. Archives of Internal Medicine 157: 777-782.

- Bikhchandani S, Hirsh Leifer D, Welch I (1998) Learning from the behavior of others: conformity, fads, and informational cascades. Journal of Economic Perspectives 12(3): 151-170.

- Brown W (1995) States of injury: Power and freedom in late modernity. Princeton University Press, Princeton, USA.

- Buvinic M, Morrison A (1999) Violence as an obstacle to development. Inter-American Development Bank, Washington, USA, pp. 1-8.

- Buss DM (2000) The dangerous passion: Why jealousy is as necessary as love and sex. The Free Press, New York, USA.

- Cranach C, James M (1998) Homicide between intimate partners in Australia. Australian Institute of Criminology, Canberra, Australia.

- Clark R (1991) Multinational corporate investment and woman’s participation in higher education in non-core nations. Sociology and Education 65(1): 37-47.

- Clayton D, Barcel A (1996) The cost of suicide mortality in New Brunswick. Chronic Dis Can 20(2): 89-95.

- Cockburn C (1991) Men Resistance to Sex Equality and Organization. In the Way of Women, Zed Books, London, United Kingdom.

- Dollar D, Gatti R (1999) Gender inequality, income and growth: are good times good for women? World Bank Development Research Group, USA.

- Ellsberg M, Heise L, Peña R, Agurto S, Winkvist A (2001) Researching domestic violence against women: methodological and ethical considerations. Stud Fam Plann 32(2): 1-16.

- Fox JA, Zawitz MW (1999) Homicide trends in the United States. Bureau of justice statistics, Department of Justice, USA.

- Gray MM, Kittilson M Sandholtz W (2006) Women and globalization: A study of 180 countries, 1975-2000. International Organization 60(2): 293-333.

- Gilbert L (1996) Urban violence and health: South Africa 1995. Social Science and Medicine 43(5): 873-886.

- WHO (2002) World Health Organization. World report on violence and health. Geneva, Switzerland.

- Hall P (1989) The Political Power of Economic Ideas. Princeton University Press. Princeton, USA.

- Heise L, Moore K, Toubia N (1996) Defining coercion and consent crossculturally. SIECUS Rep 24(2): 12-4.

- Heise L, Pitanguy J, Germain A (1994) Violence against women: the hidden health burden. World Bank, (Discussion Paper No. 255). Washington, DC, USA.

- Hofstede G (2001) Cultures consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations. (2nd edn), Sage, Thousand Oaks, USA.

- Inglehart R, Baker WE (2000) Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. American Sociological Review 65(1): 19-51.

- Inglehart R, Norris P (2003) Rising tide: Gender equality and cultural change around the world. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- Johnson MP (1995) Patriarchal terrorism and common couple violence: two forms of violence against women. Journal of Marriage and the Family 57(2): 283-294.

- Johnson MP, Ferraro KJ (2000) Research on domestic violence in the 1990s: Making distinctions. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62(4): 948-963.

- Koukounas E, Letch NM (2001) Psychological correlates of perception of sexual intent in women. J Soc Psychol 141(4): 443-456

- Koss MP, Goodman LA, Browne A, Fitzgerald LF, Puryear G (1994) No safe heaven: Male violence against women at home, at work, and in the community. American Psychological Association. Washington, DC, USA, p. 344.

- Kruger J (1998) A public health approach to domestic violence prevention in South Africa. In: Van Eeden R, Wentzel M (Eds.), The dynamics of aggression and violence in South Africa. Human Sciences Research Council. Pretoria, South Africa, pp. 399-424.

- Leibrich J, Paulin J, Ransom R, (1997) Hitting home: men speak about domestic abuse of women partners. Violence against women: a priority health issue. World Health Organization, Wellington, New Zealand.

- Linda A (1992) Power, gender, and development: Popular woman’s organizations and the politics of needs in ecuador. Taylor & Francis Group, United Kingdom.

- Mooney J (1993) The hidden figure: domestic violence in north London. Middle sex University, London, United Kingdom.

- Osakue G, Hilber AM (1999) Women sexuality and fertility in Nigeria. In: Petchesky R, Judd K(Eds.), Negotiating reproductive rights. Zed Books, London, United Kingdom, pp. 180-216.

- Yoshihama M, Sorenson SB (1994) Physical, sexual, and emotional abuse by male intimates: experiences of women in Japan. Violence Vict 9(1): 63-77.

© 2018 Silali Gerald MB. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)