- Submissions

Full Text

Perceptions in Reproductive Medicine

Obstetrical Complications and Reproductive Outcomes of Laparoscopic Myomectomy

Alexander A Popov1*, Anton A Fedorov1, Yulia I Sopova1, Svetlana S Tyurina1 and Alexey A Koval1

1Moscow regional scientific and research institute obstetrics and gynaecology, Russia

*Corresponding author: Alexander A Popov, Moscow regional scientific and research institute obstetrics and gynaecology, 101000 Russian Federation, Moscow, Pokrovka st.22A

Submission: January 25, 2018;Published: May 31, 2018

ISSN: 2640-9666Volume2 Issue2

Abstract

Introduction: The incidence of uterine fibroid in the general female population is estimated at 20-25%. A laparoscopic approach is more advantageous than laparotomy in postoperative pain, necessity of analgesia, recovery time, febrile morbidity and blood loss. Obstetric outcomes after 415 uterine myomectomies by laparoscopic versus laparotomic approach and did not describe any uterine dehiscence or rupture before or during delivery and the principal obstetric outcomes were similar between two groups.

Material and Method: We study results of 721 myomectomies performed at 2011-2014 in our department. In 502 cases (69,9%) laparoscopic access was performed

Results: Among 721 patients only 391 answer on questionnaire of the study. 61,9% of them – 242 patients were desire for the conception. The cumulative frequency of pregnancies was 50% (121 patients). Spontaneous pregnancy accounted for 75% of this number, 25% by IVF technologies. Rate of the thirst trimester miscarriages was 8,2%.3 cases of uterine rupture in this study were registrated.

Keywords: Laparoscopy myomectomy; Fibroids; Uterine rupture; Infertility; Pregnancy after myomectomy

Introduction

Uterine fibroids are most often tumors in woman and incidence of uterine fibroid in the general female population is estimated at 20-25%. Unfortunately incidence rise up to 52% at the age above 35 years [1]. For the patients who are willing to get pregnant it is necessary to create the conditions to conception, carry pregnancy and delivery. It is high functional surgery in order to save or rehabilitate the reproductiveness. Manzo et al. [2] in 2006 study effect of intramural and subserousmyomas on in vitro fertilization cycles and their perinatal results in 421 woman and make a conclusion what uterine fibroid less when 50mm impact in IVF cycle, but point that fibroids extend then 50mm might be removed preconceptionaly.

Laparoscopic myomectomy is one of most common surgical reconstructive procedure since Semm K described it in late 1970s. A laparoscopic approach is more advantageous than laparotomy in postoperative pain, necessity of analgesia, recovery time, febrile morbidity and blood loss [3,4]. Kim M [5] studyobstetric outcomes after 415 uterine myomectomies bylaparoscopic versus laparotomicapproach and did not describe any uterine dehiscence or rupture before or during delivery and the principal obstetric outcomes were similar between two groups [5]. Uterine rupture after laparoscopic myomectomy is a rare complication as in shown on several case reports [6,7].

A group of researchers from Italy confirmed the effectiveness and safety of “correct“ myomectomy Italian multicenter study on complications of laparoscopic myomectomy, Sizzi et al. [8]. The authors analyzed the results of more than 2,000 laparoscopic myomectomies and obtained the following results: hematoma at the uterine suture in 0.48% of the cases, injury to the urinary bladder in 0.04%, sarcoma in 0.09%, conversion in 0.34%, and incompetence of the uterine suture in 0.26% of the cases (on week 33 of pregnancy). Pregnancy (either spontaneous or after IVF) following myomectomy developed in 69.8% of the women.

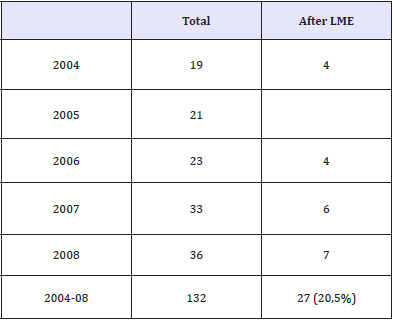

We undertook the analysis of the frequency of compromised uterine suture after myomectomy documented In Moscow during the period from 2004 to 2008 (Table 1). This condition was found to occur in each fourth patient of the total of 132 cases (i.e. 27 or 20.5%). Certain consistent patterns were revealed. Specifically, most pregnant women suffered scar rupture during weeks 30-34 of pregnancy. The rupture was most frequently localized at the bottom of the uterus and its posterior wall. Myomectomy was indicated when the woman had small interstitial nodes measuring 3-4cm. 70% of the patients had no sutures placed of the myometrial defects (Figure 1). We think that it is the main cause behind such high frequency of post-myomectomy complications.

Figure 1: Second look laparoscopy 6 month after surgery-defect of uterine wall after myomectomy.

Table 1: The frequency of incompetence of the uterine suture (Moscow, from 2004 to 2008).

Materials and Methods

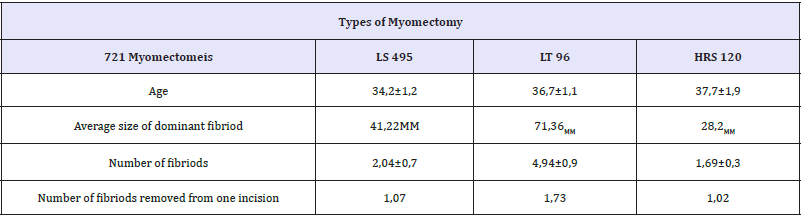

Table 2: Types of myomectomy.

We study results of 721myomectomies performed at 2011- 2014 in our department. In 502 cases (69,9%) laparoscopic access was performed, 97(13%) were operated by laparotomy, 141 patients (19,5%) were treated transcervicaly (resectoscopic myomectomy). We registrate significant increase of open access in myomectomy in 2011-2014 versus 2005-2010. Previously open myomectomy rate was 2-7%. Types of approaches, size and number of removed fibroids presented in Table 2. The indications for the surgical intervention included symptoms of uterine fibroid, such as hemorrhage, cavity deformations, and some times the size of the tumour more than 4-5cm. An additional indication was the growth of myoma in the period of preceding pregnancy.

Result

Among 721 patients only 391 answer on questionnaire of the study, 61, 9% of them-242 patients were desire for the conception. The cumulative frequency of pregnancies was 50% (121 patients). Spontaneous pregnancy accounted for 75% of this number, 25% by IVF technologies. Rate of the thirst trimester miscarriages was 8,2%. We describe 3 cases of uterine rupture in this study.

Case no 1

Complete rupture at fundus at 35 weeks of gestation. In this patient uterus perforation was detected before myomectomy during abortion. Hysteroresectoscopyc removing of type 1 fibroid 25mm located on anterior wall was performed. Spontaneously without any evidence of uterine contractions at uterine fundus arise at night time with perinatal mortality. Emergency laparotomy with hysterectomy was performed.

Case no 2

Uncomplete rupture at fundus at 33 weeks. Laparoscopic myomectomy of fibroid 60mm, located at the fundus was done. Incision was closed by single layer interrupted sutures. At ultrasound beginning of uterine rupture with scar dehiscence was detected. During emergency cesarean section scar repair were performed, baby survived.

Case no 3

Complete rupture at fund us at 38-39 weeks during labor. Previously by laparoscopy pedunculated fibroid 50mm size on the base less then 20mm was removed. Coagulation without suturing was done. During labor uterine rupture at the site of myomectomy was detected, emergency cesarean section with scar repair was done. Baby survived.

Conclusion

The following conclusions ensue:

A. Myomectomy (Lt,Ls,HRs) is a high-technology operation that must be performed strictly based on the “best” surgery for the “best” patient principle!

B. Al uterine incisions must be sutured adequately

C. Patients after myomectomy are in high risk group and must be under observation of the physician during pregnancy

D. Most uterine fibroids, especially small nodes measuring up to 4-5cm, that do not cause deformation of the uterus cavity, are asymptomatic and as a rule need not to be removed.

E. Types 0-II myomas of any size causing deformation of the uterine cavity must be removed at the stage of pregravid preparation.

F. Myomectomy is currently the method of choice for the surgical treatment at the stage of preparation for pregnancy.

References

- Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, et al. (2015) Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 136(5): E359-E386.

- De Santis CE, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Siegel RL, Stein KD, et al. (2014) Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 64(4): 252-271.

- Kwan ML, Darbinian J, Schmitz KH, Citron R, Partee P, et al. (2010) Risk factors for lymphedema in a prospective breast cancer survivorship study: the pathways study. Arch Surg 145(11): 1055-1063.

- Soran A, Ozmen T, McGuire KP, Diego EJ, McAuliffe PF, et al. (2014) The importance of detection of subclinical lymphedema for the prevention of breast cancer-related clinical lymphedema after axillary lymph node dissection; a prospective observational study. Lymphat Res Biol 12(4): 289-294.

- Lyman GH, Weaver DL, Somerfield MR, Bosserman LD, Perkins CL, et al. (2017) Sentinel lymph node biopsy for patients with early-stage breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 35(5): 561-564.

- Krok SJL, Oliveri JM, Kurta ML, Paskett ED (2015) Breast cancer-related lymphedema: risk factors, prevention, diagnosis and treatment. Breast Cancer Management 4(1): 41-51.

- International Society of Lymphology (2013) The diagnosis and treatment of peripheral lymphedema: 2013 consensus document of the international society of lymphology. Lymphology 46: 1.

- Fu MR, Ridner SH, Hu SH, Stewart BR , Cormier JN, et al. (2013) Psychosocial impact of lymphedema: a systematic review of literature from 2004 to 2011. Psycho‐Oncology 22(7): 1466-1484.

- Cheifetz O, Haley L (2010) Management of secondary lymphedema related to breast cancer. Can Fam Physician 56(12): 1277-1284.

- Stout NL, Pfalzer LA, Springer B, Levy E, McGarvey CL, et al. (2012) Breast cancer-related lymphedema: comparing direct costs of a prospective surveillance model and a traditional model of care. Phys Ther 92(1): 152-163.

- Pusic AL, Cemal Y, Albornoz C, Klassen A, Cano S, et al. (2013) Quality of life among breast cancer patients with lymphedema: a systematic review of patient-reported outcome instruments and outcomes. J Cancer Surviv 7(1): 83-92.

- Karlsson KY, Wallenius I, Nilsson-Wikmar LB, Lindman H, Johansson BB (2015) Lymphoedema and health-related quality of life by early treatment in long-term survivors of breast cancer. A comparative retrospective study up to 15 years after diagnosis. Supp Care Cancer 23(10): 2965-2972.

- Bell RJ, Robinson PJ, Barallon R, Fradkin P, Schwarz M, et al. (2013) Lymphedema: experience of a cohort of women with breast cancer followed for 4 years after diagnosis in Victoria, Australia. Support Care Cancer 21(7): 2017-2024.

- Kwan ML, Lee VS, Roh JM, Ergas IJ, Zhang Y, et al. (2015) Race/ethnicity, genetic ancestry, and breast cancer-related lymphedema. Cancer Res 75(15): 3724-3724.

- Léon KN, Ignace BK , Chantal MN, Migrette NT, John NL, et al. (2014) Massive pleural effusion after surgery of breast cancer and early discontinuation of tamoxifen: About an observation. Pan African Medical Journal 17: 129.

- Beth N, Felicity L, Mary-Anne K, Mathias F, Kaltin F (2012) Possible genetic predisposition to lymphedema after breast cancer. Lymphatic Research and Biology 10(1): 2-13.

- Jain MS, Danoff JV, Paul SM (2010) Correlation between bioelectrical spectroscopy and perometry in assessment of upper extremity swelling. Lymphology 43(2): 85-94.

- Lasinski BB (2013) Complete decongestive therapy for treatment of lymphedema. Semin Oncol Nurs 29(1): 20-27.

- Shaitelman SF, Cromwell KD, Rasmussen JC, Stout NL, Armer JM, et al. (2015) Recent progress in the treatment and prevention of cancerrelated lymphedema. CA Cancer J Clin 65(1): 55-81.

- Singh B, Disipio T, Peake J, Hayes SC (2016) Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of exercise for those with cancer-related lymphedema. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 97(2): 302-315.

- McNeely ML, Peddle CJ, Yurick JL, Dayes IS, Mackey JR (2011) Conservative and dietary interventions for cancer-related lymphedema: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer 117(6): 1136-1148.

- Doyle C, Kushi LH, Byers T, Courneya KS, Demark-Wahnefried W, et al. (2013) Nutrition and physical activity during and after cancer treatment: an American cancer society guide for informed choices. CA Cancer J Clin 56(6): 323-353.

- Christine JC, Janice NC (2013) Lymphedema interventions: exercise, surgery, and compression devices. Seminars in Oncology Nursing 29(1): 28-40.

© 2018 Alexander A Popov. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)