- Submissions

Full Text

Psychology and Psychotherapy: Research Studys

Navigating Identity: Exploring Challenges in Cultural Identity Development in Female Muslim Arab Undergraduates at an American Private University

Sawsan Awwad Tabry*

Oranim Academic College, Israel

*Corresponding author: Sawsan Awwad- Tabry, Faculty of Graduate Studies, Oranim Academic College, Kiryat Tiv’on 36006, Israel

Submission: February 9, 2024;Published: March 07, 2024

ISSN 2639-0612Volume7 Issue5

Abstract

In the context of cultural identity development, particularly within the female Muslim Arab undergraduate community at an American private university, the intricate balance between tradition and modernity poses significant challenges.

This qualitative case study examines the intricate realm of cultural identity development, examining both inter-group and intra-group conflict among female Muslim Arab undergraduates enrolled in an American private university located in the Northeastern United States. In-depth interviews, conducted in Arabic, were carried out with three Muslim Arab female undergraduates, shedding light on the multifaceted nature of cultural identity development. Students perceive this process as a continual balancing act encompassing selfhood, gender, religion, and ethnicity, occurring through interactions with fellow Muslim Arab peers on campus and the broader American student community. As our findings illuminate, personnel in international and student affairs offices must cultivate a profound awareness of the intricate dynamics of selfhood within the cultural identity development of Muslim Arab female undergraduates, fostering a more inclusive and supportive educational environment.

Keywords:Cultural identity development; Female muslim arab undergraduates; Inter-group conflict; Intra-group conflict; American private university; Northeastern United States; In-depth interviews; Selfhood; Gender and religion; Ethnicity

Introduction

Individuals across cultures face a universal dilemma: the ongoing struggle to reconcile modern lifestyles with traditional values. Nydell [1] delved into this intricate balance within the Arab world, highlighting the challenges of identity formation amidst the dynamic interplay of tradition and modernity. Specifically, Nydell discussed how Arabs in the Arab world “agonize about their identity and what constitutes appropriate lifestyle choices,” and explained how “balancing between the modern and authentic traditional way of life is a concern among Arabs in all levels in society...” (p. 11). She further maintained that many modern educated Arabs have “a dual personality” in their own countries because their lives combine and appreciate traditionalist and odernist thought. The question arises as to whether such dualism is adhered to by Muslim Arab ethnic groups on U.S. campuses and whether this dualism causes inter and intra-group conflict for Muslim Arab female undergraduates.

Materials and Methods

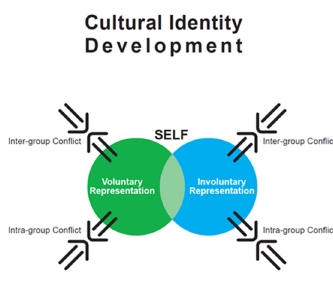

This research utilized a systems approach to cultural identity development [2]. Inter and intra-group conflict was employed as a frame by which to examine participants' perceptions of their identity as students connected to Muslim Arab as well as to American students on campus. For the purposes of this research inter and intra group conflict was examined. Inter-group cultural identity was defined as the cultural identity of the individual that is comprised of belonging to two or more cultural groups. Intra-group cultural identity is the cultural identity of the individual that is comprised of belonging to the perceived major cultural group of the individual.

This exploratory case study was conducted at one American private university in New England. In-depth, open-ended, semi-structured interviews were conducted in Arabic with three Muslim Arab female undergraduates; Hala, Soraya, and Zainab. Respondents were Palestinian Muslim Arabs from Jordan. Narrative inquiry was utilized to obtain a deeper understanding of cultural identity development as perceived by the participants. Each interview lasted approximately 80 minutes, was conducted in Arabic, audio-taped, translated into English, and then transcribed by the authors for analysis. As part of the analysis, interview transcripts were coded for emerging relationships and patterns in the data and across the three interview transcripts.

Result and Discussion

Muslim Arab female undergraduate students perceived inter and intra group cultural identity development as being related to the conflict between voluntary and involuntary representation of self. Voluntary representation of self was perceived by the participants as an act of willingly explaining oneself, one's background, culture, and or anything related to their original context of belonging. In contrast, involuntary representation of self was perceived as reluctantly having to represent oneself, one's background, culture, and or anything related to the identity witnessed, sometimes erroneously by another from a differing culture.

For two of the three interviewees, having to represent themselves involuntarily was related to inter-group cultural identity development. However, while they believed it was their role to represent their culture or religion in a foreign country, the pressure they experienced from their American peers or the wider American community to provide explanations for their behaviour, e.g. dress code, was perceived as annoying. Hala expressed her frustration by saying,

"The thing I can most relate to is my hijab… Sometimes when you think about it, your behaviour’s, the way you dress… People asked me 'How can you wear this, why do you wear it when you go to the beach…?' Yeah, this was frustrating".

While Zainab described a similar sense of frustration with this type of questioning, for her it was the way the questions were asked by her American peers that frustrated her most. She even stressed that she did not mind their questions,

"Actually, it's part of the reason I decided to keep my dress, I wanted to talk more, and show people that people like me are civilized, and that I'm happy the way I am…"

However, Zainab's voluntary representation of self was circumvented by her sense that sometimes the reason behind these questions was not a genuine interest to learn about her. She recalled,

"But I had people who asked me, "Why are you wearing this, in a weird way. I mean they know why I'm wearing this, but they ask me, ‘Are you crazy’? You know, just to provoke me".

Interestingly, Zainab reported that she did not manifest her true emotional response to having to involuntarily explain herself against such "provocative questions". She said,

"I wouldn't disregard them or anything, I would still answer, but it would give me a kick inside". This "kick inside"

This “kick inside” that Zainab talked about during the interview was the only way in which she would express her reaction. Hence, in each case of conflict related to involuntary representation, both Hala and Zainab resolved the conflict by drawing on their obligation to represent themselves regardless of the perceived provocation which they experienced in their interaction with Americans.

Moreover, the fact that Zainab came from Jordan was perceived by her Jordanian counterparts as necessitating that she behaved in certain ways which represented their shared culture. When she didn’t, they reminded her of where she came from. Hence, Zainab experienced conflict related to voluntary and involuntary representation of self as she perceived it coming from her Jordanian Arab counterparts on campus. She said,

"I had problems from some of these Arabs telling me ‘Why are you doing this or that, you're from Jordan…"

Similarly, Soraya recounted an incident wherein Muslim Arab girls on campus harassed her for not using the traditional Muslim greeting when she ran into them on campus. Soraya told the following incident:

“I don’t have to show [my piety]. People try to make me look like I’m not religious at all. You know how we say our Greetings. I go like, even back home when I talk to my father- I go like: Hi Keefak (how are you?). And he goes: Hi, Keefek? One day, there were those Arab girls on campus, and I said Hi, and one of them said: Say: Asslam Alaikom (Peace be upon you, i.e. the traditional greeting in Islam), we're Muslim”.

This incident indeed exemplified the conflict that Soraya perceived as being related to the pressure exerted by her intra-group counterparts, i.e. Muslim female Arab peers, to involuntarily represent herself in light of Muslim traditions when living in a foreign county.

Interestingly, all three respondents, who experienced conflict between voluntary and involuntary representation of self, acted as agents of that same type of conflict towards their counterparts, i.e. the other Muslim Arab students on campus. Hala talked about how excited she was when, for the first time in her life, she had met so many Arab students on a campus. She further said,

“They're from the Gulf. I have never in my life met Arabs from that part of the Arab world. It was the first time for me. Even meeting female students from there, for me it's a new experience. When I met two females from there last semester there was so much, I wanted to learn, we used to sit together to talk, I had so many questions for them. I was curious about their lives and the details of their daily living. I wanted to know everything”.

In her own words, Hala was saying that she expected other Muslim Arab non-Jordanian counterparts on campus to act involuntarily as representatives of their own countries and cultures of origin in just the same way that her American host community expected her to involuntarily represent her own culture, religion, and background. Thus, all three Muslim Arab female undergraduate students in this study perceived their cultural identity development as being related to the conflict between voluntary and involuntary representation of self. It was noteworthy that the two respondents who chose to keep their hijab and modest dress code while living and studying in an American private university reported this type of conflict the most.

All three respondents in this study demonstrated a multifaceted portrait of self when describing how they perceived their cultural identity development in an American private university. In this study, perceptions of self-referred to the versatile components that comprised and configured an individual's voluntary and involuntary delivered self-portrait. During the interviews, this multifaceted and hence versatile portrait of self often represented conflicting perceptions of the voluntary or involuntary self of the respondents. All three research participants experienced, in several different ways and degrees, conflict that was related to the perceptions they held of themselves as they moved between voluntary and involuntary representation of self. Soraya identified her perception of 'core identity' as being independent of, and unaffected by any religious pressure around her. This sense of what she saw as the manifestation of her voluntary representation of self was in conflict with the involuntary sense of self that was seen by her Muslim Arab peers who, in their part, exerted on her enormous social pressure to behave in certain ways:

“Yeah, I’m not really conservative, I’m not very religious, but it’s like for me, if you believe in something it’s for you, you don’t have to go tell everyone that: Oh… I pray 700 times a day. You don’t do that. It’s something between you and your God… you don’t have to show”.

While Soraya's conflict resulted from her core sense of self and the involuntary sense of self that was monitored by her religious Muslim counterparts on campus, Hala expressed conflict that was related to her own perception of core identity as opposed to the pressure to involuntarily represent herself to her American peers. Hala recalled that when she first came to the university, she

"Felt it (the head cover) was strange to others. They never saw a woman with a hijab before".

She was perceived as the 'other' by surrounding Americans and that often required some explanations on her part. Hala also struggled as she realized that while there existed a voluntary sense of self, and indeed Hala stated that she felt good about how she represented herself, she felt she did not know herself well enough to be able to explain it fully to others. Nevertheless, she was willing to sit with Americans who were interested in her and had questions about her religion and dress. Here is how Hala described her conflict:

“ … People would come to me and ask me ‘Why are you wearing a hijab? We want to sit with you and talk with you. We want to understand more about this hijab…’ I had to read more, even about my own religion, I didn’t know the answer to many of their questions, and I felt I had to provide information, ask my husband… Sometimes you want to explain to them but you can’t explain everything, every detail, you have to read, have the background and information about the subject”.

Hala lacked the experience and the skill to explain her most essential decision regarding her core religious identity and its manifestation in her dress. She felt the need to do some research at home in order to educate herself and return to those around her with answers and information about her religion and religious customs. While Hala did not complain about having to explain, she did talk about the pressure she felt as a result of having to provide these explanations. Zainab's experience with her hijab was similar to Hala's. She, too, accepted the fact that her voluntary sense of self was perceived as 'other' by virtue of her traditional Islamic dress and head cover which invited explanation.

However, the difference with Zainab was that she made a distinction between the different kinds of questioning she encountered as a result of being perceived as the 'other'. She explained:

“Some people never saw or even talked to an Arab who looked like myself… I'm happy the way I am, I didn't mind answering their questions as long as they come from a person who really wants to know, not from a person who’s trying to discriminate me or to insult me or look down on me, or provoke me onto saying something I didn’t wanna say. For both Hala and Zainab, the voluntary representation of self was in conflict with that which was seen and perceived as the 'Other'. In addition, their reactions differed due to their different personalities and experiences and consequently, their conflicts were perceived as different”.

Zainab described her experience during her first weeks in the dorms:

“I had a triple room with two roommates, one American and one Chinese. The American wasn't happy that she had two international roommates… And of course, you can feel when somebody isn’t happy with something… and after one month she moved out which was good”.

This recollection of Zainab's first encounter with social isolation in an American university was caused by her being perceived as the 'other'. Hala told a similar story where she felt isolation, albeit in the subtlest forms,

I feel that I’m not related to them (American students), I’m strange to them… I didn’t feel comfortable.“I felt that even when I took it (the head cover) off, people still looked at me the same way… Even though I did not hear any offensive remarks from anybody, there were looks”.

Whether these 'looks' were actual or perceived, one can never tell but unlike Zain, Hala was surprisingly very understanding, permissive, and even forgiving of her American peers' perception of her as the 'other'. She elaborated,

“People have the right to look at me and wonder about the hijab. It’s OK if they ask questions to learn more, I understand that they’re not used to seeing somebody with a hijab. I don’t blame them. Besides, I never heard anything negative from anybody regarding my hijab. People are simply interested in knowing more and they showed real interest by asking: How did you choose it, why do you wear it?”

Hence, while the effect of Hala's conflict was directed inwardly and was more related to her perceived need to constantly explain herself and religion to the external environment, Zainab's choice to be selective as to who deserved to receive her explanation was based on her perception and judgment of the attitude of the external environment itself towards her.

Additionally, Hala and Zainab spoke about incidents wherein they were being mistaken for the 'other'. They told stories about Americans assuming they were Iraqis just because they wore their head covers or because they were known to be Muslim. Once again, Hala was accepting of the fact that her sense of 'self' was mistaken for the 'other'. She recalled:

"More people were interested to know about me or my religion, sometimes they talked about the War on Iraq, they wanted to know more from me".

Hala seemed to be fine with that. She reported that although it exerted pressure on her because she didn’t know much about the situation Iraq, she was willing to do some research on her part and bring answers back to her peers.

Zainab also experienced being mistaken for the 'other'. She reported that …some people never saw or even talked to an Arab who looked like me.

“Some of these people only saw people who looked like me on TV, and got affected by, you know, media, propaganda. Some people asked me if I was Iraqi because they thought only Iraqi women looked like me”.

Zainab did not mind clarifying that while she was an Arab, she was not an Iraqi. She did not even talk much about the issue of being mistaken for an Iraqi. However, she did emphasize the fact that she perceived the source of her conflict to be related to her being perceived as a Muslim on campus,

"I think that in my case I was more frustrated because of being a Muslim and because I wear my scarf, I look like a Muslim more than likely being identified as an Arab. I wasn't discriminated because of being Arab, but because I was Muslim. It shows, and I'm proud of being a Muslim, it's not a secret, I talk about being a Muslim and I'm Arab as well, it's a connected thing."

Zainab further explained that she was convinced that her being perceived as the 'other' was solely due to the fact that she wore her head cover. In other words, her conflict was perceived to be related to her essential 'Me' that looked different and was automatically perceived as different. Zainab elaborated:

“Well, I haven’t experienced being around this kind of environment without showing off my identity as a Muslim, but I think so, in my case I think so, because being an Arab you can be an Arab and still not look Arab…I think it would've been easier if I was looked at only as an Arab and not as a Muslim, if I didn’t wear this it would've been easier. Especially when during classes, we as Arabs don’t stand out, some of us have the Middle Eastern touch on them, but if it weren't for their accent, the way they talk, I don't think they really stand out as Arabs”.

Interestingly, while Zainab did not report having hesitated nor questioned her need to manifest her Islam by wearing her head cover, Hala reported that she did:

“I took it off for only a short time one day, when I went to the grocery store. I didn’t go to the mall or spend a whole week or more than that… [but] I didn’t feel comfortable. I felt that even when I took it off, people still looked at me the same way… Now I know I’m doing the right thing by wearing it”.

Thus, both Zainab and Hala's voluntary representation of self was in conflict, though in different ways, with the identity that was perceived or mistaken for the 'other', or involuntary representation of self which invited explanation. Each in her own case demonstrated this conflict.

Conclusion

Developing a cultural identity was perceived by the respondents as oftentimes demanding a balance between the various facets of identity; i.e. sense of selfhood, gender, religion, ethnicity, race, culture, and nationality. This was reported to occur while interacting with Muslim male and female Arab peers on campus as well as with the surrounding American student community. Social, cultural, and religious codes of behaviour that represented their original identity were sometimes perceived as threats to cultural identity development within the new environment. As a result of this perceived cultural disparity, the respondents found themselves having to operate in two public cultures simultaneously; the tradition-bound, collectivistic culture of the Muslim Arab world represented by Muslim Arab peers on campus, versus the liberally individualistic culture of west represented by American peers and the wider American community. The emerging duality of functioning in public strained the participants into weighing their identity choices within the two existing, and sometimes contradictory, social contexts.

As a result, a process of evolving intercultural identity emerged as the respondents experienced conflict caused by incidents of involuntary representation of self. In other words, when the respondents had to expose and explain themselves to Arab peers or the surrounding American community, their involuntary self-representations was conflict oriented and conflict-laden. Interestingly, inter-group and intra-group conflict occurred simultaneously for these Arab Muslim females while participating on campus. In particular, the respondents experienced conflict related to pressure exerted by Muslim female Arab peers to involuntarily represent Muslim traditions when living in a foreign county.

In general, the Arab Muslim community on campus posed more pressure and strain on the respondents to involuntarily represent themselves than it facilitated their assimilation of American culture. When the respondents were unable to perform the required or expected behavior, they reexamined the way they perceived their cultural identity by retrieving back to their core identities; i.e. sense of selfhood, and acted accordingly. As a result, self-isolation from the intra-group identity was oftentimes enacted by the participants. Muslim Arab female undergraduates perceived their cultural identity development as being related to having to consciously and constantly navigate between voluntary and involuntary acts of self-representation. In other words, core identities, private identities, and public identities had to be examined and reexamined in an ever-evolving process of intercultural identity development (Figure 1).

Given intercultural identity development, it was found that the core identity may actually be a starting point from which individuals can step away and into new circles of identity formation as they interact with differing cultural identities. Accordingly, these identities can "touch and join one another" or "separate and diverge" [3]. Consequently, such an "interface" can influence identity formation by the "construction, negotiation, expansion, and transformation of identities" (p. 7) resulting in an ever evolving inter-cultural identity.

Figure 1:Cultural identity development model.

In essence, this study highlights the dynamic nature of intercultural identity development [4], revealing that one’s core identity serves not as a fixed destination, but rather as a launching pad for exploration and growth. As individuals engage with diverse cultural identities, they navigate a complex web where identities intersect, merge, or diverge. This continual interaction fosters a fluid process of construction, negotiation, and transformation, leading to the emergence of an ever-evolving inter-cultural identity. Thus, understanding this intricate interface is crucial for comprehending the multifaceted journey of identity formation in our increasingly diverse world.

References

- Nydell MK (2006) Understanding Arabs: A Guide for modern times. Intercultural Press. Boston, London.

- Ruben B, Kim J (1975) General systems theory and human communication. Hayden Books, Rochelle Park, USA.

- Kim Y (1994) Beyond cultural identity. Intercultural Communication Studies 1(4): 1-24.

- Mir S (2014) Muslim American women on campus: Undergraduate social life and identity. UNC Press Books. North Carolina, USA.

© 2024 Sawsan Awwad Tabry, This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)