- Submissions

Full Text

Psychology and Psychotherapy: Research Studys

Overcoming Organizational Chaos in Schools through Team-Based Productive Conflict

Christopher Benedetti*

Associate Professor, Department of Educational Leadership, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi, USA

*Corresponding author: Christopher Benedetti, Associate Professor, Department of Educational Leadership, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi, USA

Submission: September 19, 2023;Published: October 11, 2023

ISSN 2639-0612Volume7 Issue4

Abstract

Today’s schools are challenged to constantly change in an effort to meet seemingly never-ending policies and demands, which can leave schools in a varied state of chaos. Chaos can be a natural part of change, and if managed effectively, should be controlled and eventually eliminated once the change is complete. Schools, however, are in a constant battle with chaos in an effort to maintain an environment always ready for change. As a result, poorly managed organizational chaos can be detrimental to a school’s success. Schools can apply a tiered, cyclical model for overcoming organizational chaos using established team structures as a vehicle to control and transform the chaos into productive conflict. This model has several steps, including acknowledging and identifying the chaos and related components, as well as engaging teams in productive conflict through promoting adaptability and establishing shared beliefs and values and the team and school levels.

Keywords:Beliefs; Values; Staff turnover; Toxic culture; Chaos theory; Guiderails

Introduction and Background

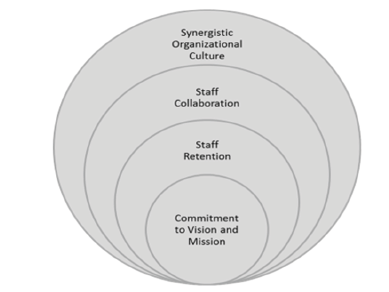

Today’s schools are in a constant cycle of change in an effort to meet never ending demands of the education landscape, which can leave schools in a varied state of chaos. Organizational culture, a complex and intertwined phenomenon captured in Figure 1, is affected by this chaos, is an often-overlooked part of the performance of a school. However, a strong organizational culture helps to promote student success through productive staff collaboration, low staff turnover, and overall commitment to the school vision and mission [1]. A negative organizational culture creates stress [2] and dysfunction among staff and the school community, ultimately serving as a distraction to instruction and student learning. Negative organizational cultures also generate shared pessimistic beliefs and values about the organization, which can lead to reduced job satisfaction and collective staff turnover [3].

Figure 1:Layered complexity of organizational culture.

Conceptual Framework

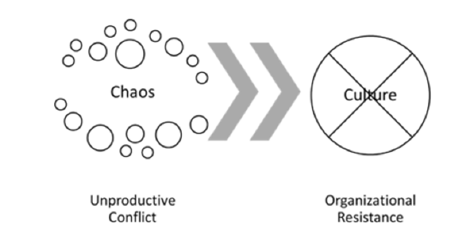

Schools are in a constant battle with chaos to maintain an environment always ready for change. As a result, poorly managed organizational chaos can create a negative organizational culture. This chaos can also lead to members of the organization to become disengaged from the organization, which includes distrust, reduced job satisfaction, and turnover [3]. Ultimately, a school with poorly managed organizational chaos will be unable to meet current demands and face future changes successfully. The concept of organizational chaos is derived from the Chaos theory, which states (when applied to organizations), that organizations can experience chaos during change while still maintaining some level of order through foundational beliefs and practices [4]. Chaos can be a natural part of change, and if managed effectively, should be controlled and eventually eliminated once the change is complete. Complications to change that lead to organizational chaos include a lack of structures, poor communication, and toxic culture. Structures serve as the guiderails during change to ensure momentum maintenance. Without these guiderails, change can become unmanageable. Poor communication during change creates confusion and uncertainty about what is needed to move the change forward. Toxic culture, which is the source of many organization-related issues, is often a product unproductive conflict as noted in Figure 2.

Figure 2:Influence of conflict and resistance on organizational culture.

A key sign of the emergence of poorly managed organizational chaos is the increase in conflict. Before individuals can resolve conflicts, they must understand the nature of their conflict. In organizations, conflicts can be classified into four categories: Task conflict, process conflict [5], role conflict and relationship conflict [6]. In contrast, productive conflict is a strategy used to manage conflict and produce outcomes that move individuals beyond the conflict. Productive conflict entails an active exchange of listening, creative exploration, and ultimately compromise. In essence, conflict still exists because individuals are discussing disagreements, but with the intended purpose of resolution. Most teachers possess some experience with conflict resolution as a function of working with students, but the skills may not necessarily be transferrable.

Discussion

tiered, cyclical process of overcoming organizational chaos in schools, noted in Figure 3, has several steps, including: acknowledging the chaos impacting the organizational culture, identifying the conflict within the chaos [6], defining the team to lead conflict resolution efforts, engaging the team in productive conflict, erasing the negative collective memory [7], promoting adaptability [8] and learning within the team, building a set of shared beliefs and values [9] and ultimately resetting the culture of the organization. Most teachers in schools are already structured into teams, such as those within a department or subject area. As a result, teachers can initially work within these existing teams to begin the process of productive conflict. Once these teams have successfully completed the process, the cycle begins again with multiple teams, such as another grade level or subject area team. This cyclical process would continue until all school teams have successfully participated, which then allows the school to establish a new organizational culture to better manage chaos as it emerges.

Figure 3:Cyclical process to manage chaos in schools.

Conclusion

Organizational chaos may be inevitable given the everchanging nature of the many influencing and impeding forces faced by organizations. Schools are not immune to these forces. However, the already-embedded structures in most schools provide an advantage given teacher proximity and ongoing collaborative opportunities that may not exist in larger and siloed organizations. Schools must take advantage of these opportunities. Stripping emotion from conflict, which is also inevitable, will help teachers to move to a productive mindset, driven by the goal of managing any incoming chaos in ways that maximize beneficial outcomes.

References

- Anteby M, Molnar V (2012) Collective memory meets organizational identity: Remembering to forget in a firm’s rhetorical history. Academy of Management Journal 55(3): 515-540.

- Heavey A, Holwerda J, Hausknecht J (2013) Causes and consequences of collective turnover: A meta-analytic review. J Appl Psychol 98(3): 412-453.

- Jacobs D (2007) Controlling organizational change: Beyond the nightmare. Journal of the Quality Assurance Institute 21(4): 19-23.

- Jehn K, Bendersky C (2003) Intragroup conflict in organizations: A contingency perspective. Research in Organizational Behavior 25: 189-244.

- Lee M, Louis KS (2019) Mapping a strong school culture and linking it to sustainable school improvement. Teaching and Teacher Education 81: 84-96.

- Ravasi D, Schultz M (2006) Responding to organizational identify threats: Exploring the role of organizational culture. Academy of Management Journal 49(3): 433-458.

- Senge P (1990) The leader’s new work: Building learning organizations. Sloan Management Review 32(1): 7-23.

- Shaw J, Zhu J, Duffy M, Scott K, Shih H et al. (2011) A contingency model of conflict and team effectiveness. J Appl Psychol 96(2): 391-400.

- Zhang Q, Zhu W (2008) Teacher stress, burnout and social support in Chinese secondary education. Human Communications 10(4): 487-496.

© 2023 Christopher Benedetti*, This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)