- Submissions

Full Text

Psychology and Psychotherapy: Research Studys

Resilience, Hope and Coping with Secondary Trauma: Societal Implications from a Study on Arab Teachers

Sawsan AT*

Oranim Academic College, Israel

*Corresponding author: Awwad Tabry Sawsan, Oranim Academic College, Kiryat Tivon 36006, Israel

Submission: September 15, 2023;Published: October 02, 2023

ISSN 2639-0612Volume7 Issue4

Abstract

This study investigates the relationships between resilience, hope, and secondary trauma among Arab teachers in Israel, an under-researched area. The research is crucial for educational leaders in developing effective coping strategies for teachers. Using a quantitative cross-sectional design, 129 teachers from diverse regions in Israel’s Arab community participated. They completed an online survey that included scales for Resilience, hope, and secondary traumatization. Results showed a positive correlation between resilience and hope, while both were inversely related to secondary trauma. Resilience emerged as a significant predictor of secondary trauma, but hope did not. No age-related differences in secondary trauma were observed. The findings highlight the importance of fostering resilience and hope as protective factors against secondary trauma. These insights can inform tailored intervention programs that emphasize nurturing resilience and hope in educators. Such efforts can mitigate secondary trauma, enhance teacher well-being, and contribute to a more resilient and effective educational system.

Keywords:Secondary trauma; Resilience; Hope; Teachers; Culture; Arab society

Introduction

Secondary trauma manifests as post-traumatic symptoms, particularly relevant for Arab teachers in Israel exposed to students’ accounts of violence and loss [1-4]. Such exposure risks teacher fatigue and burnout, affecting educational quality [5]. This study addresses this underexplored area to enhance teachers’ resilience.

The Arab education system

Arabs, constituting 21.1% of Israel’s population, face systemic challenges [6,7]. The Arab education system serves over 500,000 students but lags in resources and faces societal issues like violence [8,9], elevating teachers’ risk of secondary trauma [10-12]. Previous research has mainly addressed structural disparities in Arab education [11]. Some studies discuss teacher well-being [13,14], but literature on coping with secondary trauma is limited [10,11]. This study explores the relationship between resilience, hope, and secondary trauma in this context. Resilience, as defined by the American Psychological Association (APA), is key to teachers’ coping mechanisms and is linked to positive outcomes like job satisfaction and effectiveness [15,16]. It is shaped by various factors, including early experiences and social influences [17,18].

Hope

Central to belief in positive change and personal efficacy, hope enhances teachers’ motivation and resilience [19,20]. However, literature lacks insight into its role among Arab teachers facing unique societal challenges [10,11].

Secondary trauma

Secondary trauma is marked by intense reactions similar to primary trauma symptoms like hopelessness, and is prevalent among professionals, particularly teachers, due to their roles and interactions with those in distress [1,2,21]. Research highlights the need for enhanced support systems [22]. The current study explores the links between resilience and hope as independent variables and secondary trauma as the dependent variable, while also comparing secondary trauma levels between older and younger teachers. The findings could inform programs that train teachers in coping with secondary trauma and enhancing resilience and hope.

Research Questions

Main research questions

Is there a connection between resilience and hope and secondary trauma among teachers in Arab society? Secondary research question: Are there differences between older and younger teachers at the level of secondary trauma?

Research hypotheses

H1: Resilience and hope among teachers will be positively

correlated; specifically, as the resilience level of teachers

increases, their level of hope is also expected to rise.

H2: Resilience among teachers will be negatively associated

with secondary trauma; with higher resilience levels leading to

lower reported levels of secondary trauma.

H3: Hope among teachers will be negatively associated with

secondary trauma; specifically, as teachers report higher levels

of hope, their secondary trauma levels are expected to decrease.

H4: Age will be inversely associated with reported levels of

secondary trauma among teachers; older teachers will report

lower levels of secondary trauma compared to younger

teachers.

H5: In Arab society, resilience and hope will significantly predict

secondary trauma levels among teachers.

Methodology

Employing a quantitative cross-sectional approach, the study surveyed 129 Arab teachers in Israel using an online questionnaire. The survey, disseminated via social media, assessed resilience, hope, secondary trauma, and demographics. Data were analyzed with SPSS27, adhering to ethical standards for anonymity [1,2,23].

Study Variables

Dependent variable

Secondary trauma, characterized by negative physiological and mental responses to another’s trauma,was measured using the SRPSS by Figley & Kleber [1,2,23].

Independent variables

Resilience, defined as the capacity to cope and recover from adversity, was assessed using the Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) by Smith et al. [15,24]. Hope, defined as optimism in uncertain situations, was measured using Snyder et al.’s Hope Scale [19,25]. Demographic variable included age, categorized by the study’s median age.

Study Participants

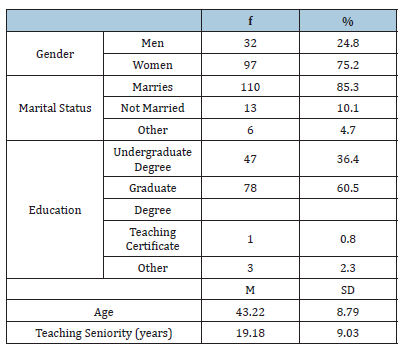

Utilizing convenience sampling, this study engaged 129 Arab teachers in Israel. Of these, 75.2% were women and 85.3% were married. Educational levels varied, with 36.4% holding a bachelor’s degree and 60.5% a master’s degree. The sample averaged 19 years of teaching experience. The mean and median ages were 43 and 44, respectively, and the sample was nearly evenly split between younger (48%) and older teachers (52%) (Table 1).

Table 1:The sample population (N=129).

Findings

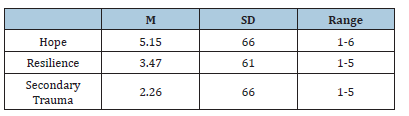

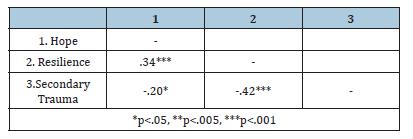

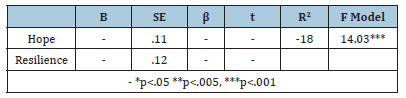

The study revealed several findings. First, resilience and hope were found to be closely related; teachers who reported feeling resilient also felt hopeful. Second, resilience appeared to serve as a protective factor against secondary trauma, indicating its role as a psychological shield. Third, a strong sense of hope was similarly associated with lower levels of trauma, suggesting its potential as a buffer against traumatic stress. However, when examining predictors of secondary trauma, resilience emerged as a significant factor, while hope did not exert the same influence. Interestingly, age did not appear to influence the experience of secondary trauma, defying expectations that older or younger teachers might differ in this regard (Table 2-4).

Table 2:Means and standard deviations of the study variables (N=129).

Table 3:Correlations between the study variables (N=129).

Table 4:Linear regression findings for predicting secondary trauma (N=129).

Conclusion and Implications

The study underscores the need to foster resilience and hope among teachers, especially in marginalized communities. Findings show a positive link between resilience and hope, and suggest these traits act as protective factors against secondary trauma. The study emphasizes the importance of resilience as a key predictor of secondary trauma, while age was not a factor. Teacher support extends beyond academics to societal roles, including fostering community resilience [24,26]. Cultural context, such as community support in Arab society, adds nuance to these findings and may be a vital resilience source [23,27]. The results could guide training programs focused on coping and resilience.

Limitations and Research Implications

The study’s reliance on convenience sampling limits generalizability, suggesting future research should employ random sampling for broader applicability. The use of self-reported data introduces potential response bias, warranting the inclusion of objective measures in subsequent studies. Lastly, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inference, recommending that future work utilize longitudinal methods to establish directional relationships between resilience, hope, and secondary trauma [28-31].

References

- Lawson HA, Caringi JC, Gottfried R, Bride BE, Hydon SP (2019) Educators' secondary traumatic stress, children's trauma, and the need for trauma literacy. Harv Educ Rev 89(3): 421-519.

- Miller K, Stipp KF (2019) Preservice teacher burnout: Secondary trauma and self-care issues in teacher education. Educ Res 28(2): 28-45.

- Atkins MA, Rodger S (2016) Pre-service teacher education for mental health and inclusion in schools. Exceptionality Educ Int 26(2): 93-118.

- Namminga C (2021) Secondary trauma: How does it impact educators (a literature review presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of master of education). Northwestern College, India.

- Brandt ASC, Santacrose DE, Barnett ML (2020) In the trauma-informed care trenches: Teacher compassion satisfaction, secondary traumatic stress, burnout, and intent to leave education within underserved elementary schools. Child Abuse Negl 110(3): 104437.

- Israeli central bureau of statistics. Demographics, Israel.

- Rouhana N, Khoury AS (2019) Memory and the return of history in a settler-colonial context: The case of the Palestinians in Israel. Int J Postcolonial Stud 21(4): 527-550.

- Nasra MA, Arar K (2020) Leadership style and teacher performance: Mediating role of occupational perception. Int J Educ Manag 34: 186-202.

- Rahmoun NA, Goldberg T, Barak LO (2021) Teacher evaluation policy in Arab-Israeli schools through the lens of micropolitics: Implications for teacher education. Eur J Teach Educ 44: 348-364.

- Haj MA (2020) Arab local government in Israel, Routledge, New York, USA, p. 226.

- Fakhoury MT, Alfasi N (2017) From abstract principles to specific urban order: Applying complexity theory for analyzing Arab-Palestinian towns in Israel. Cities 62: 28-40.

- Eyal M, Bauer T, Playfair E, McCarthy C (2019) Mind-body group for teacher stress: A trauma-informed intervention program. Spec Group Work, pp. 204-221.

- Tabry SA, Levkovich I, Pressley T, Altman SS (2023) Arab teachers’ well-being upon school reopening during COVID-19: Applying the job demands-resources model. Educ Sci 13: 418.

- Boneh MZ, Schaal RF, Bivas TA, Saad AD (2022) Teachers under stress during the COVID-19: Cultural differences. Teach Theory Pract 28: 164-187.

- American Psychological Association (2014) Guidelines for psychological practice with older adults. Am Psychol Assoc 69(1): 34-65.

- Y Wang (2021) Building teachers’ resilience: Practical applications for teacher education of China. Front Psychol 12: 738606.

- Simone JAD, Harms PD, Vanhove AJ, Herian MN (2017) Development and validation of the five-by-five resilience scale. Assessment. 24(6): 778-797.

- Harms PD, Brady L, Wood D, Silard A (2018) Resilience and well-being, In: Diener E (Ed.), Handbook of well-being, DEF Publishers, Utah, US.

- Snyder CR, Harris C, Anderson JR, Holleran SA, Irving LM, et al. (1991) The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. J Pers Soc Psychol 60: 570-585.

- Berger R, Raiya HA, Benatov J (2016) Reducing primary and secondary traumatic stress symptoms among educators by training them to deliver a resiliency program (ERASE-Stress) following the Christchurch earthquake in New Zealand. Am J Orthopsychiatry 86(2): 236-251.

- Levkovich I, Ricon T (2020) Understanding compassion fatigue, optimism and emotional distress among Israeli school counsellors. Asia Pac J Couns Psychother 11: 159-180.

- Levkovich I, Gada A (2020) The weight falls on my shoulders: Perceptions of compassion fatigue among Israeli preschool teachers. Asia Pac J Couns Psychother 4(3): 91-112.

- Figley CR, Kleber RJ (1995) Beyond the victim secondary traumatic stress. In: Kleber RJ (Ed.), Beyond trauma: Cultural and societal dynamics, Plenum Press, New York, USA, pp. 75-98.

- Smith BW, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, et al. (2008) The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. Int J Behav Med 15: 194-200.

- Pleeging F, Exel JV, Burger M (2022) Characterizing hope: An interdisciplinary overview of the characteristics of hope. Appl Res Qual Life 17(3): 1681-1723.

- Harker R, Pidgeon AM, Klaassen F, King S (2016) Exploring resilience and mindfulness as preventative factors for psychological distress burnout and secondary traumatic stress among human service professionals. Work 54(3): 631-637.

- Dwairy M (2019) Culture and leadership: Personal and alternating values within inconsistent cultures. Int J Leadersh 22(4): 510-518.

- Meler T (2017) The Palestinian family in Israel: Simultaneous trends. Marriage Fam Rev 53: 781-810.

- Yahia MMH (2019) The Palestinian family in Israel: Its collectivist nature, structure, and implications for mental health interventions. In: Yahia MH, Nakash O, Levav I (Eds.), Mental Health and Palestinian Citizens in Israel, Indiana University Press, Indiana, USA, pp. 97-120.

- (2023) The Jerusalem Post.

- Nolan C, Stitzlein SM (2011) Meaningful hope for teachers in times of high anxiety and low morale. Democracy and Education 19(1): 2.

© 2023 Sawsan AT*, This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)