- Submissions

Full Text

Psychology and Psychotherapy: Research Studys

New Psychological Safety Regulation in Australia is Forcing Organizational Leaders to Address Demand for Improved Mental Health Initiatives in Workplaces

Coventry P*

South Australian Health & Medical Research Institute (SAHMRI), Australia

*Corresponding author: Petrina Coventry, South Australian Health & Medical Research Institute (SAHMRI), Level 7 Office 7.209, North Terrace Adelaide SA 5000, Australia

Submission: June 22, 2023; Published: July 03, 2023

ISSN 2639-0612Volume7 Issue2

Abstract

Psychological safety regulations introduced in Australia in 2023 Emphasize Organisations must proactively accommodate mental health issues and introduce policy and programs. Anxiety, which is the most commonly experienced mental health condition, remains a gap in Occupational Health and Safety and Human Resource research and practice. It can affect productivity. Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) and Human Resource Managers (HRM) are often held accountable for Health, Safety and wellbeing programs and are increasingly interested in ways to improve in the area of mental health. A study outlining how anxiety impacts productivity, the efficacy of wellbeing programs to deal with mental health and wellbeing, and perspective of OHS and HRM to be able to deal with the challenge was conducted during 2022 in Australia with enrolled members of the Australian Institute of Health and Safety (AIHS), the peak body for Occupational Health and safety (OHS) and leading Human Resource Managers (HRM). Existing information was investigated through a literature review, and new information was gathered through a Quantitative study including a Self-Administered Questionnaire (SAQ) in the form of an online QALTRICS survey n=152 and a subsequent Qualitative Study used Semi structured interviews with OHS and HRM professionals n=5.

Thematic analysis was used to analyze and triangulate and the data to identify factors influencing awareness of, barriers to, and success around organizational wellbeing programs in relation to anxiety. Indication are that OHS and HRM cohorts (over 76%) perceived that management lack skills to recognise when anxiety or wellbeing was an issue, anxiety can affect productivity yet research gaps around anxiety exist, and employee awareness of wellbeing programs remains low (below 50%). Conclusions are that although anxiety is the most commonly experienced mental health condition [1] wellbeing programs do not typically address anxiety and despite regulation increasing, wellbeing program efficacy remains in question.

Keywords:Psychological safety; Anxiety; Wellbeing; Productivity; Occupational health and safety

Abbreviations:OHS: Occupational Health and Safety; HRM: Human Resource Management; AIHS: Australian Institute of Health and Safety; SAQ: Self-Administered Questionnaire; PSC: Psychosocial Safety Climate; ACQ: Anxiety Coping Mechanisms; EAP: Employee Assistance Programs

Background

A literature review was undertaken to determine existing knowledge and evidence regarding anxiety as a condition, its effect on workplace productivity, as well as the utility and effectiveness of existing workplace psychological health and safety programs to deal with anxiety. A computer-assisted literature search was conducted using the following databases: EBSCO Host including Academic Search Premier, PsycArticles, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, PsycBooks, PsycInfo; Sage Psychology Journals; Proquest Psychology Journals; Science Direct Social and Behavioral Sciences; and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. Books, reports, and original research articles were included, Preference was given to literature published in the last ten years, and unpublished materials such as dissertations, theses, and peer reviewed papers presented at recent professional meetings not yet in published form. Studies included in the literature review covered meta-analyses, and general integrative research that related to psychological and sociological reviews of research into OHS, HRM, wellbeing, health and safety, and anxiety as a factor in performance. The findings are summarized in the following segments.

Anxiety as a condition

Anxiety is an emotion that has been with us as long as we have been in existence. It rests on the mental health continuum between stress and depression. Stress can be situational and short lived around an event, anxiety can be longer term, defined by persistent, excessive worries that don’t go away even in the absence of a stressor. Anxiety triggers fear or panic and create an automatic response in our brain serving a purpose to protect us from harm. Triggers may be real or perceived and past patterns of reaction are embedded in the subconscious brain. When anxiety occurs, the conscious mind is not in control, taking a back seat to subconscious automatic responses enacted out of embedded memories and patterns of behavior intended to protect us [2-4]. Diagnosis of an anxiety disorder is not necessary to determine its effect. It is a normal human emotional condition. Emotions can impact employees and are important to understand in the context of the workplace [5]. Long term, chronic anxiety can be unhealthy if left unaddressed, leading to depression, substance abuse, and other serious issues which can be harder and more costly to treat. Early detection and intervention into anxiety can mitigate employees and organizational risk and cost [6].

Covid 19 pandemic impact

The pandemic has not only challenged employees physical health, but also psychological and social well-being, resulting in increases mental health conditions like anxiety [7]. Businesses were forced to shut down, with employees encouraged to work from home and front-line staff working in essential services such as hospitals were forced to adapt to the significant risk presented by the virus at their workplace [8-11]. Employees have been impacted through stalled career planning, fungible work allocations, income stagnation, health threats, social restrictions such as isolation and emotional dynamics including peer pressure around to Vaccinate or not to vaccinate. These pressures have increased feelings of anxiety. There is no doubt this pandemic has had both a short term and long-term impact on both employees and organizations.

New health and safety regulations

In parallel to increasing pressure around organizations to improve profitability, regulation and governance in the area of workplace psychosocial risks and safety is also increasing [12]. In Australia the management of psychosocial health and safety risks in workplaces has historically been unregulated [13]. However, in response to multiple OHS policy and legislative reviews [14], additional regulations have been introduced from 2022 [15,16]. As a consequence, employers now have increased responsibility to prevent psychosocial risk in the workplace by designing effective, proactive mental health and wellbeing workplace systems.

Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) and Human Resource Managers (HRM) often share responsibility for the design and management of organizational health and wellbeing systems, and they continue to partner and galvanize around the need for improvement. Unfortunately, there continues to be gaps in research, knowledge, and measurement in this area, with a lack of empirical studies and publications in HRM and OHS peer reviewed literature describing analysis, impact and accurate measurement of programs that deal with the issue of anxiety and the effectiveness of workplace mental health interventions.

OHS and HRM galvanization

During the pandemic the disciplines of OHS & HRM were often coordinated around employee health and safety initiatives [17], but decision making was immediate and very action oriented. The longer-term planning around mental health and wellbeing programs requires a shared responsibility and shared goals to be achieved. OHS plays a role in facilitating this, but equal accountability rests with HRM in developing the culture of an organization. Developing a “Safety First” culture requires forward thinking and proactive decision-making processes, not always evident during the peak of Covid 19.

Wellbeing program efficacy

For every $1 invested in treating depression and anxiety, there is a $4 return for the economy yielding a 5% improvement in workforce participation [18]. Despite a strong Return on Investments (ROI), there is ongoing debate around the effectiveness and worthiness of investments of programs that deal with mental health issues such as anxiety [19-21]. Debate is often cantered around the continued rise in long-term absences, work injury claims, and incapacity costs attributed to mental disorders [22]. Research conducted in 2017 indicated that 80% of employees rate their company’s support for mental health as poor [23,24]. Challenges continue around the disparate, and often confusing offerings that are provided by OHS, HRM and other wellbeing consultants. This reflects the organic way in which many of these programs have developed.

Materials and Methods

During the literature review there were evident gaps in OHS and HRM peer reviewed literature [25] driving the need to establish new information [26,27]. New information in this study was created through quantitative and qualitative research conducted with the Australian Institute of Health and Safety (AHS) members and leading HRM practitioners. The study was designed to test the perceptions of OHS and HRM towards anxiety and the efficacy of workplace wellbeing programs to deal with the issue. The study was conducted in Australia during the pandemic, using mixed method research and leveraged an interdisciplinary approach across OHS and HRM. Research instruments included a literature review, a quantitative surveys and qualitative interviews. Thematic analysis, and triangulation of all data points was used to arrive at the conclusions and make recommendations that could easily be operationalized by OHS, HRM and other organizational leaders.

The study evaluated:

a) Anxiety as a condition,

b) OHS & HRM knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes towards

anxiety,

c) Current state of wellbeing offerings to deal with anxiety in the

workplace,

d) Recommendations for wellbeing program design and

implementation.

Quantitative research

A Self-Administered Questionnaire (SAQ) was distributed to members of the Australian Institute of Health and Safety (OHS cohort) and HRM leaders in Australia. The SAQ leveraged previously validated theories from the fields of psychosocial safety and OHS which included: Psychosocial Safety Climate (PSC); Perceived Control Over Anxiety Related Events, and Anxiety Coping Mechanisms (ACQ). Participants were asked about changes they have seen or experienced in the workplace in relation to their understanding of the concept of anxiety, and their perception of the quality and performance of organizational health and safety interventions in relation to anxiety. The 57-item SAQ included background information and context that introduced anxiety, psychological issues in workplaces, as well as informal and formal solutions to be considered.

Questions were grouped into sections that included

Demographics. This included gender, age, years of working experience and role within their organization. Demographic factors were used as independent variables during data analysis to determine demographic similarities or differences. Perceived impact of everyday anxiety on self (participant) and others (colleagues) in the workplace. Perceived control of anxiety-related events and anxiety control mechanisms including individual, management, and workplace strategies developed to help cope with anxiety. Psychological safety culture and management mechanisms including OHS systems. Open-ended questions and observations to gain information that might be important to reinforce the formal questions from the SAQ and to inform recommendations.

Participant profile

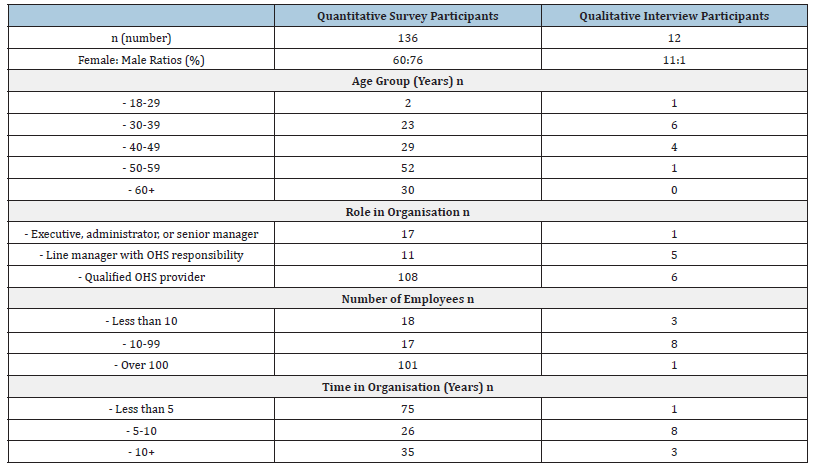

A purposive sample was created from those with OHS and HRM expertise who had health and well-being as the primary function of their role [28]. The respondent profiles is seen in Table 1.

Table 1:Respondent profile.

Result and Discussion

Only responses that showed full completion were included in the analysis. The results of the SAQ showed positive correlations between management’s behavior relating to the psychological safety climate, wellbeing, and its importance to productivity. A number of analytical tests were conducted to include reported frequencies (percentages) for discrete factors with a small number of levels and means (SD) and median (ranges) for summary scales. Covariate adjusted and unadjusted binomial or proportional odds models were used to compare differences between HR and OHS respondents for dichotomous and ordinal survey outcomes. Covariate adjustments were considered for age (continuous), gender (M v F), years in role (continuous), organization size (<10 v 10-99 v 100+) and organization type (Public v NFP v Other). There were different results between OHS and HRM participant in how management deals with psychological wellbeing and how they act when a concern for psychological wellbeing is raised. HRM considered that they act more rapidly with regard to psychological safety related issues and communicate with their employees better than the OHS cohort. OHS participants rated themselves lower in terms of considering psychological safety of an employee and in acting quickly or decisively if an issue occurs in the workplace. This could be important to impart to both disciplines, as alignment between the two fields could strengthen the goal to improve communication and action in organizations.

Early determination and containment

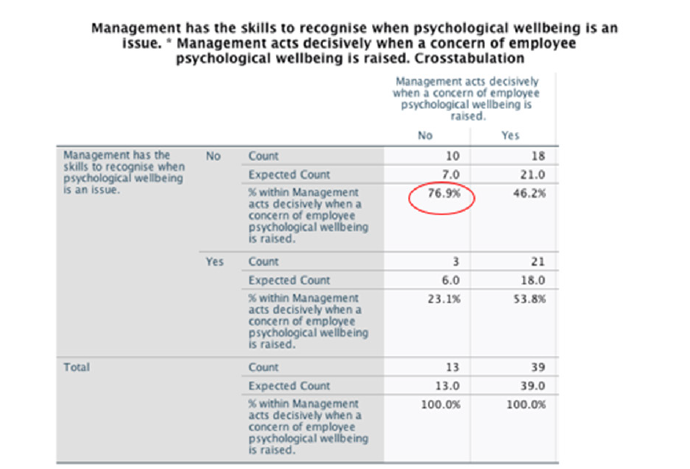

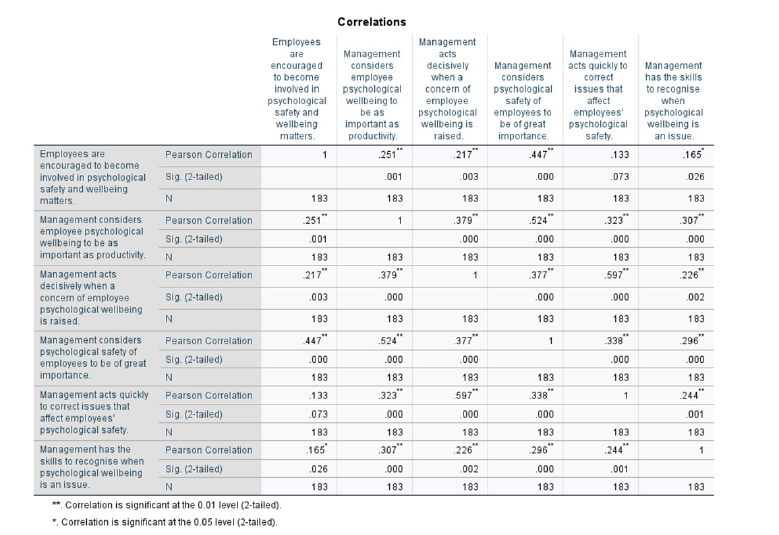

A key issue in dealing with anxiety is to act early to prevent longer term, more costly and difficult to treat issues related to depression or other conditions. The ability to interpret when and how to act on anxiety is predicated on having the skills to do so. Both OHS and HRM cohorts (over 76% ) indicated that management did not have the skills to recognise when poor wellbeing was an issue, or to be able to act decisively when an issue is raised as seen in Figure 1. Hypothesis tests were run around variables that may improve the early determination, or containment. A combination of variables was tested using Pearson two tail correlation as seen in Figure 2. Correlations can be observed between questions related to psychological well-being and safety of staff is a priority for this organization and questions related to Management acts decisively when employee psychological wellbeing is raised. Correlation strength could be considered as moderate (not low) where psychological safety is considered important, actions are taken, and communication is strong around the issue.

Figure 1: Management did not have the skills to recognise when poor wellbeing was an issue, or to be able to act decisively if psychological wellbeing is raised.

Figure 2: H1 test, if an employee’s psychological wellbeing is raised, management acts decisively.

Awareness of wellbeing programs

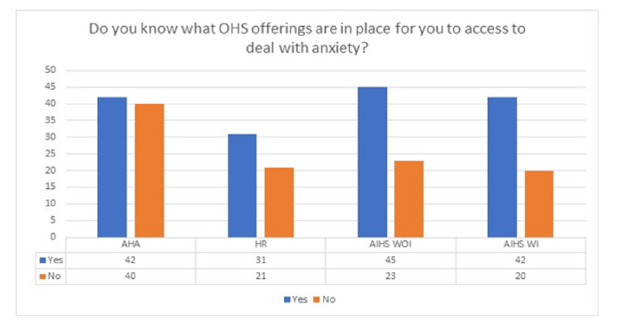

From 51 survey participants, 40 responded NO when asked Do you know what OHS offerings are in place for you to access to deal with anxiety? and views expressed in the open questions reinforced that they did not know what wellbeing programs existed in their workplace as seen below in Figure 3. From the literature review, recent studies indicate that only 31.4% of workers reported that their workplace would consistently provide programs to support their mental health and only 23.7% of organizations provide programs to support employee wellbeing [29].

Figure 3: Awareness of OHS programs deal with anxiety.

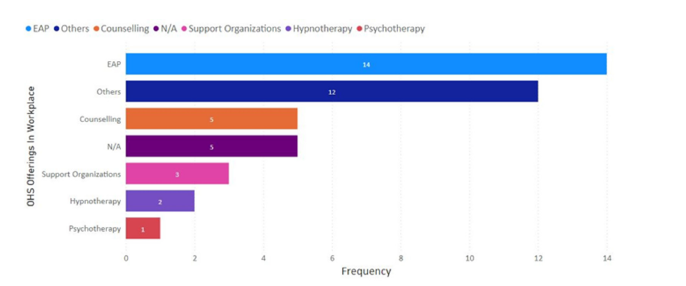

Program classification

Where knowledge of wellbeing programs did exist, the majority of respondents cited the provision of Employee Assistance Programs (EAP) to help employees deal with anxiety. A smaller percentage of participants were aware of counselling services, and other support organizations and psychotherapy being offered in their workplace as seen in Figure 4 below. Organizations often engage EAPs to assist employees experiencing psychological distress, yet EAPs primarily focus on individual remedies rather than addressing the context of the problem (e.g., the corporate climate), which may render them limited in effectiveness [30]. The over reliance on EAP to address the issue of anxiety reinforces the need and opportunity to strengthen research around what is effective. Anxiety as a subconscious condition needs subconscious solutions [5]. If wellbeing program offerings do not match the situation or problem, low receptivity and utilization rates may render them ineffective [19].

Figure 4: Categories of wellbeing offerings.

Emerging themes

Thematic analysis uncovered perceptions around anxiety, its impact and barriers surrounding psychological safety and wellbeing mental health programs. Barriers that surfaced in relation to acceptance of anxiety as a workplace issue, included poor disclosure, overcoming stigma, and ability to recognise anxiety as a condition as well as the “Unknowns” of how to deal with it. Themes are reinforced with direct comments made from participants in the qualitative interviews.

Theme 1-Lack of acceptance of anxiety as an issue

Participants felt anxiety is poorly acknowledged as an issue in the workplace. The senior staff support their employees; however, they are less likely to recognize a day needed for mental well-being over a day off for personal care. It is like-they don’t understand the relationship my anxiety has with my output. (Participant #1). Acknowledging and accepting anxiety as a problem and a barrier to employee wellbeing and organizational productivity will start to encourage the adoption and delivery of programs by OHS & HRM. I think a lot of people just consider anxiety to be on the same level as stress. Stress is more temporary and is usually related to something which suggests we can fix it. I think a lot of people would challenge this if they knew more about it and accepted its place in our life. (Participant #2) The COVID-19 pandemic offered an opportunity for organizations and individuals responsible for wellbeing to highlight the existence and importance of employee anxiety, or loss of liberty and control, and for some a sense of uncertainty. COVID-19 really changed how I viewed anxiety. I guess I always thought of it as something weak people had or something that people needed to just get over. Now I get that anxiety is real, especially now that my workplace really hasn’t embraced how it has impacted our daily lives and how some people simply cannot deal with it. May be work could have done something to alleviate some of the issues. (Participant #3). Anxiety can be nebulous, difficult to diagnose, and under reported condition, continued exploration of the mind’s role on the issue of productivity and performance is required [31].

Theme 2-disclosure & stigma

The second consistent theme related to employee obligation or feelings of responsibility to or comfort in disclosing anxiety. There is no obligation for workers to disclose information about their wellbeing. It is a personal decision and depends on the circumstances, the context, and the perspective of how the employee disclosing their health might impact their work or standing with the organization. Employees may have past experience of being discriminated against and this too may affect how they communicate their wellbeing. I wouldn’t dare tell the people around me at work anything about my personal life. You don’t know who will share what story with who and what will end up happening. (Participant # 4) The pervasiveness of stigma means the prospect of disclosing anxiety to an employer can be frightening. Many employees choose to avoid disclosure by keeping their anxiety private. Sometimes, performance issues are related to the cognitive symptoms of an undiagnosed, untreated, or recurring mental health problem of which the employer is unaware. An employer may mistakenly conclude that the performance issues reflect lack of commitment, lack of ability or a bad attitude. An employee may feel that full or partial disclosure is the best option when the employer has started to question the employee’s performance.

I don’t want my superiors to know that COVID-19 worries me. I really have deep concerns for my parents during this time and how restrictions will impact our life. I don’t need problems at work on top of this. I just keep my concerns to myself. (Participant # 7) Disclosure has implications for both the employer and employee and relates to the culture of the workplace. Developing the culture of safety first often requires forward thinking and a proactive decisionmaking process. Addressing fear and stigma around mental health, and anxiety will be critical to ensure that it is reported, and that employees can receive the appropriate treatment or solution early.

Theme 3-HRM & OHS differ in views around wellbeing

As outlined earlier, the field of HRM plays an important role in the support and sometimes direct supervision of OHS in organizations. This collaboration continues to increase, with the two functions becoming more galvanized during the pandemic to co-ordinate workforce health and safety. There is an opportunity for the disciplines to share their expertise, and to co-ordinate effectively on planning, implementation, and communication. This in turn offers both disciplines some extended career and development opportunities for the future. The challenge is that the functions of HRM and OHS do not always align with their strategy or communication. I am not sure what OHS offer, I know what we (HRM) offer, it would help to know more about what they (OHS) can do to help us participant # 10. Strengthening the offerings, making the programs access more available and better understood will be a goal for both functions. Both disciplines have backgrounds that can complement each other, making for a great marriage in the improvements of health and wellbeing for their organizations.

Conclusion

Psychological safety regulations introduced in Australia in 2023 have increased the interest and emphasis around how to deliver effective mental health policy and programs in workplaces. Anxiety is the most commonly experienced mental health condition and recognized as a factor affecting productivity. Anxiety levels have increased due to the challenges and adjustments faced during the Pandemic [8]. Although anxiety affects an individual’s performance and productivity it remains misunderstood, misinterpreted and neglected as a condition across many industries and to date psychological safety and wellbeing programs are considered to have mixed results with regard to dealing with the issue. OHS and HRM are typically held accountable for mental health, safety and wellbeing programs. They continue to galvanize in their organizational duties; however, each discipline bring different backgrounds, education and perspectives with gaps remaining in OHS and HRM research. The research included in this paper indicates that awareness of workplace programs dealing with anxiety is low, skills in recognizing anxiety are poor, barriers to selfawareness and reporting includes stigma associated with mental health concerns, and that there is an over reliance on generic Employee Assistance Programs (EAP).

Existing research from the literature review indicates that with wellbeing programs no single intervention works well in isolation, with recommendations that a package of offerings should exist. Interventions specifically found to be useful with regard to anxiety centered around enhancing employee self-awareness and control, promoting physical activity, and offering suitable cognitive behavior therapy. Quantitative data in the research project conducted with AIHS indicated that where management did have the skill to identify an issue, timely action to deal with it increased. Anxiety requires early identification and timely action in order to prevent further deterioration which can be more costly to deal with. Mental health programs can be cost-effective and counteract productivity loss, absenteeism, job abandonment, and higher turnover [32,33], however employers often find it difficult to be informed purchasers due to the disparate set of offerings and wide range of delivery modalities including online, telephonic, and face-to-face products. It is felt that many mental health providers deliver a single component of a comprehensive solution, resulting in a patchwork of uncoordinated programs, often delivered by multiple vendors, with limited consistency or integration [19] and that too many off-theshelf generic wellbeing products mean individual needs or specific situations are not met [19,34]. Due to the recognised research gaps and increased regulation in the eater of psychological safety and mental health, there is growing interest among policymakers, academics, and organization to improve the understanding around the relationship between mental health and work performance [35]. This includes a better understanding of subconscious and tacit knowledge connecting anxiety and performance due to the emotional individual nature of the condition [36-39].

There is increased interest and importance in studying how health, safety and wellbeing interventions affect social or organizational climates [31] and OHS and HRM are increasingly being held to dual accountability but both fields generally lack peer reviewed research, while extant research has focused on alleviating symptoms and risk factors associated with mental disorders, less emphasis has been placed on gathering evidence around anxiety. There are academic, industry and social implications and significance for improved research, as it can inform: Research institutions, OHS & HRM providers who are assessing workplace anxiety treatments; individual employees impacted by anxiety; their families, their colleagues, organizational leaders and the broader community [40].

Limitations

This study was conducted in Australia which may limit the generalizability of the results to other markets and countries. Broader applicability of these findings should consider factors such as: epidemiological data on the prevalence of anxiety as a mental condition in populations and in workplaces; specific risk factors associated with different employment sectors; systems that are or can feasibly be put in place to manage anxiety; and the extent of legislation and laws implemented. The sample size of N=51 meets research standard but would be strengthened with larger cohort participants. All observational studies have attached bias. The participants selection process was open to selection bias as it participants who were interested in the study may result in distorted outcomes. Selection bias is often found in program interventions where participants self-select into wellbeing programs. In this study the effect of wellbeing on anxiety in the organizations may be more effective for those employees who are more in need of the assistance. Because mental health conditions often overlap, it is difficult to discern results attributable to the treatment of anxiety. Mixed results in empirical studies have at times included anxiety as a condition, but not specifically anxiety with ramifications that the condition can be under-recognized and often untreated.

Disclosure

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was sought through the University of Adelaide Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) and approved on 24/03/2022. The approval number is H-2022-053. HREC protocols are in line with research that includes studies of this nature within Australian Universities.

Informed consent

Informed consent was gained from all participants prior to any data gathering. The informed consent included information regarding the study, contacts for any conflict or concern and the ability to sign online. Withdrawal from the program did not incur any penalty at any stage.

Registry and the registration no. of the study/trial

Registration was sought through the Adelaide University Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) in line with National Health and Medical Research Centre (NHMRC) ethical guidelines and the ethical approval registration no. is H-2022-053.

References

- (2006) Anxiety Disorders; Anxiety disorders association of America survey finds Americans report stress, anxiety. ADAA, Mental Health Business Week, USA, p. 9.

- Salario A (2012) The fear & anxiety solution: A breakthrough process for healing and empowerment with your subconscious mind. Spirituality & Health Magazine, USA, p. 90+.

- Lanius RA, Rabellino D, Boyd JE, Harricharan S, Frewen PA, et al. (2017) The innate alarm system in PTSD: Conscious and subconscious processing of threat. Curr Opin Psychol 14: 109-115.

- Graeff FG, Zangrossi JH (2010) The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in anxiety and panic. Psychology & Neuroscience 3(1): 3-8.

- Coventry P (2022) Occupational health and safety receptivity towards clinical innovations that can benefit workplace mental health programs: Anxiety and hypnotherapy trends. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(13): 7735.

- Birnbaum HG, Kessler RC, Kelley D, Hamadi RB, Joish VN, et al. (2010) Employer burden of mild, moderate, and severe major depressive disorder: Mental health services utilization and costs, and work performance. Depress Anxiety 27(1): 78-89.

- Mula AM, Abella JD, Mortier P, Narváez PC, Vilagut G, et al. (2022) The impact of COVID-related perceived stress and social support on generalized anxiety and major depressive disorders: Moderating effects of pre-pandemic mental disorders. Annals of General Psychiatry 21(1): 7.

- Prado CBD, Emerick GS, Pires LBC, Salaroli LB (2022) Impact of long-term COVID on workers: A systematic review protocol. PloS One 17(9): e0265705.

- Giorgi G, Lecca LI, Alessio F, Finstad GL, Bondanini G, et al. (2020) COVID-19-related mental health effects in the workplace: A narrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(21): 7857.

- Han S, Choi S, Cho SH, Lee J, Yun JY (2021) Associations between the working experiences at frontline of COVID-19 pandemic and mental health of Korean public health doctors. BMC Psychiatry 21(1): 1-298.

- Ikegami K, Ando H, Fujino Y, Eguchi H, Muramatsu K, et al. (2022) Workplace infection prevention control measures and work engagement during the COVID‐19 pandemic among Japanese workers: A prospective cohort study. J Occup Health 64(1): e12350.

- Lerouge L (2017) Psychosocial risks in labour and social security law a comparative legal overview from Europe, North America, Australia and Japan, 1st (edn), Aligning Perspectives on Health, Safety and Well-Being. Cham: Springer International Publishing, USA.

- Michael T, Nicholas B (2016) Employment law: Improving wellness in the workplace: Think holistically and beyond. Governance Directions 68(8): 497-499.

- Potter R, Keeffe OV, Leka S, Webber M, Dollard M (2019) Analytical review of the Australian policy context for work-related psychological health and psychosocial risks. Safety Science 111: 37-48.

- Lamp (2021) More protection against psychosocial hazards: Employers and managers now have a clear responsibility to protect workers from psychosocial hazards at work, thanks to a new Code of Practice developed by a working group that included the NSWNMA. Lamp 78(4): 19.

- Goss JR (2022) Health expenditure data, analysis and policy relevance in Australia, 1967 to 2020. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(4): 2143.

- Obeidat MS, Sarhan LO, Qasim TQ (2022) The influence of human resource management practices on occupational health and safety in the manufacturing industry. Int J Occup Saf Ergon, pp. 1-15.

- Gulland A (2016) Mental health ROI, Sweden.

- Spence GB (2015) Workplace wellbeing programs: If you build it they may NOT come…because it’s not what they really need! International Journal of Wellbeing 5(2): 109-124.

- Gallagher C, Underhill E, Rimmer M (2003) Occupational safety and health management systems in Australia: barriers to success. Policy and Practice in Health and Safety 1(2): 67-81.

- Murray MK, (2015) Derailed Organizational interventions for stress and well-being confessions of failure and solutions for success. (1st edn), In: Murray MK, Biron C (Eds.), Springer Dordrecht, Germany.

- Riba MB, Parikh SV, Greden JF (2019) Mental health in the workplace: Strategies and tools to optimize outcomes, (1st edn). Integrating Psychiatry and Primary Care, Springer International Publishing, USA.

- Calnan M, Wainwright D, Forsythe M, Wall B, Almond S (2001) Mental health and stress in the workplace: The case of general practice in the UK. Soc Sci Med 52(4): 499-507.

- Reichert AR, Tauchmann H (2017) Workforce reduction, subjective job insecurity, and mental health. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 133: 187-212.

- Fan D, Zhu CH, Timming AR, Su Y, Huang X, et al. (2020) Using the past to map out the future of occupational health and safety research: where do we go from here? The International Journal of Human Resource Management: Annual Review, In: Parry E, Dickmann M, Cooke FL (Eds.), 31(1): 90-127.

- Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldaña J (2014) Qualitative data analysis : A methods sourcebook. (3rd edn), In: Matthew BM, Huberman AM, Saldana J (Eds.), SAGE, Los Angeles, USA.

- Farschtschian F (2011) Research methodology. Springer Berlin/Heidelberg: Germany, pp. 51-57.

- Guba EG, Lincoln YS (1989) Fourth generation evaluation. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications, USA.

- Carolan S, Harris PR, Cavanagh K (2017) Improving employee well-being and effectiveness: Systematic review and meta-analysis of web-based psychological interventions delivered in the workplace. J Med Internet Res 19(7): e271.

- Bouzikos S, Afsharian A, Dollard M, Brecht O (2022) Contextualising the effectiveness of an employee assistance program intervention on psychological health: The role of corporate climate. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(9): 5067.

- Veld M, Alfes K (2017) HRM, climate and employee well-being: Comparing an optimistic and critical perspective. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 28(16): 2299-2318.

- Chisholm D, Sweeny K, Sheehan P, Rasmussen B, Smit F, et al. (2016) Scaling-up treatment of depression and anxiety: A global return on investment analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry 3(5): 415-424.

- Naydeck BL, Pearson JA, Ozminkowski RJ, Day BT, Goetzel RZ (2008) The impact of the highmark employee wellness programs on 4-year healthcare costs. J Occup Environ Med 50(2): 146-156.

- Baicker K, Cutler D, Song Z (2010) Workplace wellness programs can generate savings. Health Aff (Millwood) 29(2): 304-311.

- Beijer SE (2014) HR practices at work: Their conceptualization and measurement in HRM research. UK.

- Bertrams A, Englert C, Dickhäuser O, Baumeister RF (2013) Role of self-control strength in the relation between anxiety and cognitive performance. Emotion 13(4): 668-680.

- Eysenck MW, Calvo MG (1992) Anxiety and performance: The processing efficiency theory. Cognition and Emotion 6(6): 409-434.

- Philippi CL, Koenigs M (2014) The Neuropsychology of self-reflection in psychiatric illness. J Psychiatr Res 54(1): 55-63.

- Voorde KVD, Beijer S (2015) The role of employee HR attributions in the relationship between high‐performance work systems and employee outcomes. Human Resource Management Journal 25(1): 62-78.

- Geisler M, Berthelsen H, Muhonen T (2019) Retaining social workers: The role of quality of work and psychosocial safety climate for work engagement, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance 43(1): 1-15.

© 2023 Coventry P, This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)