- Submissions

Full Text

Psychology and Psychotherapy: Research Studys

A Reconsideration of Premorbid Factors in Conversion Disorders

Luuk Stroink1* and Klaas Huijbregts2

1Revalis Rehabilitation Centre, Netherlands

2Scelta Centre of Expertise for Personality Disorders, Netherlands

*Corresponding author: Luuk Stroink, Revalis Rehabilitation Centre, Netherlands

Submission: June 07, 2023; Published: June 20, 2023

ISSN 2639-0612Volume7 Issue1

Abstract

Conversion disorder, also referred to since DSM-5 as functional neurological symptom disorder is a difficult condition to understand. Over the years, much has been hypothesised about the Etiology, starting with descriptions of hysteria and trauma. The scientific focus has shifted from psychological explanations to psychological treatment of conversion disorder. The emphasis lies on the consequences of the problem and changing coping mechanisms in relation to the problem. A multifactorial stress model is being used due to the lack of empirical evidence for a causal relationship between trauma and the development of a conversion disorder. The aim of this article is to introduce a new hypothetical working model about conversion disorder. First, we present an overview of different etiological psychological explanations. Then we introduce the new hypothetical working model that still needs empirical investigation. The working model integrates both premorbid and sustaining factors and may provide leads for a transcending approach. The idea behind this is that treatment that also targets premorbid factors may be more enduring and effective.

Introduction

Around 1850, Martin Charcot introduced the term hysteria, which he believed to be a neurological condition until shortly before his death [1]. He described motor disorders such as paralysis, extreme immobility, bizarre movements or difficulty walking and convulsions of hands and legs. He also described sensory complaints, such as loss of taste, sight and feeling disorders and pain. In this respect he also referred to psychiatric disorders, such as behavioural problems, memory loss, dissociation, doubling of the personality, an uncontrollable urge to walk or wander, kleptomania and the urge to spend to excess. It was supposed that hysterical patients would present with symptoms in four phases, including noticeably bizarre manifestations, such as the arc de cercle or arch of hysteria, and erotic poses. He described the fact that patients presented as if they were unconcerned with their symptoms, for which he coined the term ‘la belle indifference [2,3]. Another striking concept that was described by Charcot in this period in relation to the group of hysterical patients was the idea of suggestibility. According to Charcot, patients appeared to be highly likely to accept other people’s suggestions. The symptoms that Charcot described and suggested that he saw in patients were probably easily adopted by patients. That can be explained by the historical texts that demonstrate how Charcot repeatedly saw the symptoms he was describing in his patients. What was revealed, however, was that the symptoms described by Charcot hardly ever arose in a similar manner after his death [1]. Shortly before his death, Charcot published an article in which he described the fact that the condition of hysteria could actually be a psychological condition [1], which would imply a hysterical personality, a term that would later be adopted by his successors [4,5].

Psychological explanations

Trauma and dissociation as an explanation: A student of Charcot’s who developed a psychological explanation for hysteria was Pierre Janet [5]. He focused on trauma and dissociation as the explanation for the symptoms [4]. He made a distinction between primary and secondary states of consciousness. The primary states of consciousness correspond to the protective factors that come to the fore so that the patient does not have to dwell on memories of traumatic experiences. The secondary states of consciousness are the split sections (ego states) of the consciousness that are traumatic and include flashbacks. The mechanism of dissociation, arising from anxiety about feelings (affect phobia), segregates the secondary states of consciousness from the primary consciousness, [4]. He hypothesised that these secondary states of consciousness, which he called idées fixes or fixations, became disengaged, split factors within a hysterical patient’s personality. In his opinion, a treatment should focus on integrating the primary and secondary states of consciousness (the traumatic experiences), in which the disengaged idées fixes could be reconnected to the awareness.

Freud & Breuer [4] were inspired by the ideas of Janet [5] and Charcot [2] and developed the idea of trauma and dissociation in their book Studies on Hysteria. Traumatic neurosis was assumed to be the most significant trigger and Breuer believed that hysterical symptoms would disappear immediately and not return once the memory of the traumatic event had been deactivated with the causal effect of the traumatic event. In the case of hysteria or a hysterical (histrionic) personality, dissociation may manifest itself earlier than is the case with other personalities due to sensitivity to hypnosis [4]. In Breuer’s opinion, hypnosis is a form of artificial hysteria and the solution put forward was to use a diversionary strategy to reach the causal affect that was related to the trauma. Motor and sensory symptoms are interpreted as a reaction to the splitting of the traumatic affect. This shift of split traumatic affects to motor and sensory symptoms was summarised by Freud & Breuer [4] as conversion, to which the etymology of the term refers. At a later stage, Freud went on to assume that repression was the basic mechanism of conversion, rather than dissociation. In doing so, he introduced a defence mechanism that patients developed in response to repressed traumatic events.

Yet other examples of hysteria and trauma in relation to conversion disorders came to the fore following observations made of casualties of war. Hysteria was understood to be an acute state of shock which continued to affect patients long after a battle. Examples of hysteria-related attacks were seen during the First World War in the aftermath of traumatic battles and at the time, were labelled ‘shell shock’ [5]. Soldiers succumbed to phenomena such as neurasthenia or ‘weakness of the nerves’, the symptoms of which were myoclonic twitches which had similarities to involuntary movement disorders or weaknesses. Soldiers mentioned fragmentary memories of the traumatic battle and reported dissociative complaints. One of the causes stated was that the soldiers were suffering from emotional shock that gave rise to the motor and sensory symptoms [5]. At that time, these symptoms were viewed as an extreme form of homesickness, but complaints of this nature were later labelled as elements in post-traumatic stress disorder [5]. At a later stage, trauma and dissociation were considered the factor explaining how a patient could present with somatic symptoms that could be summarised as ‘somatoform dissociation’ [6]. This theory has a similar explanation for the symptoms that had previously been described by Freud et al. [4] & Janet P [5]. Trauma and dissociation heighten a disintegration between implicit information processingwhich equates to automatic, sub-conscious information processingand explicit information processing; that corresponds to information of which the patient is conscious. Patients present with implicit information processing, which is intact, but not consciously accessible. One example of this cited by Kihlstrom [6] is the patient with conversion-related blindness who says that he cannot see yet is able to correctly identify how many fingers another person is holding up.

From trauma and dissociation to coping and sustained coping mechanisms: The psychological impact of trauma and dissociation was long retained as the model for explaining conversion disorder, but there is insufficient empirical evidence for a causal link between trauma and a diagnosis of conversion disorder [7]. It has been shown that conversion disorder patients report increased trauma and dissociative episodes [8], although there is additional evidence for conversion patients who do not report any traumatic episodes [7]. Due to the lack of evidence, trauma as an etiological factor in a diagnosis of conversion disorder has increasingly faded into the background, ultimately even disappearing from the psychiatric manuals. According to DSM-5, for instance, it is no longer necessary to have experienced a psychological stressor, such as a traumatic event, to receive a diagnosis. And psychological stressors as a condition for the diagnosis are no longer necessary according to ICD-11.

Over the past few years there has been increased attention for sustained coping mechanisms, such as attention processes, expectations about the occurrence of complaints and sense of agency [8]. Important attention processes that work differently in patients with conversion disorders include interoception and the recognition of personal emotions [9,10]. Patients may find it more difficult to recognise and interpret physical cues and to link them to emotions; they tend to focus their attention on the physical symptoms [11]. They expect and feel that they no longer have control over physical sensations [12]. The ‘sense of agency’ refers to the extent to which a patient experiences the fact that it is the patient him/herself who makes the physical movement or thinks the thoughts, and that he or she has independent control over these. Patients with an absence of ‘sense of agency’ no longer have the feeling that they can direct their bodies themselves. Strengthening the ‘sense of agency’ [13] has thus become an important starting point in the treatment of conversion disorder. This is done by teaching patients to direct their attention in a different way. By teaching patients to distract their attention (by using indirect strategies) rather than fixating on symptoms/complaints, they can gain positive movement experiences; hence their ‘sense of agency’ increases. A day-to-day example is the inability to remember a person’s name. The more someone tries to recall the name, the more that person blocks the memory pathways and fails to recall the name. When indirect strategies are used, for instance by thinking of an image or the address of the person in question, it may be possible to remember the name almost instantaneously.

Towards a multifactorial stress model: Recent research has worked to establish the etiology of conversion disorders from the perspective of a multifactorial stress model [14], in which a range of factors together make up a conversion disorder. An example of this is that factors such as trauma, psychiatric symptoms, somatic symptoms and in addition, a limited ‘sense of agency’ with abnormal attention focus on affective processes increase the chance of the development of a conversion disorder [15]. Over the past few years, research into conversion disorders has moved towards a complete network around influential variables which generally deem trauma and the processing of dissociation moderating rather than causal. Trauma and dissociation are no longer seen as ‘linearly responsible’ [16] (when the traumatic affect is felt, that results in relief of the symptoms), rather a multifactorial stress model is seen, in which factors from both the past (such as traumatic life experiences) and the present (such as the loss of a job) strengthen the psychopathology [17], causing the conversion disorder. What remains unclear in this case is the extent to which specific variables carry more weight in terms of the creation of a conversion disorder. What also remains unclear in this model is why certain factors may specifically lead to a conversion disorder.

A new hypothetical working model

Towards an integrated working model for conversion disorders: Over the years, the terminology has changed from hysteria to conversion disorders and as added to DSM-5, Functional Neurological Symptom Disorder (FND). This change reflects a shift in emphasis over time; the symptoms were initially believed to have psychological causes, whereas now the focus is on the effects. This makes it clear that the role of premorbid psychological processes in the research become vaguer, while sustained psychological influences are not denied. The term ‘premorbid factors’ refers to those factors that one assumes are existing before the pathology develops. Firstly, we present an underlying theory that is called the theory of autonomy-connectedness. It is possible that premorbid vulnerability factors that play a significant role in the conversion disorders can be explained from the perspective of this yet relatively unknown theory. Then, we discuss the connection between autonomy-connectedness and variables that are highly interconnected and are known from the literature on conversion disorders. Finally, we present an integrated working model that can serve as a hypothetical working model for clinical practice.

Autonomy-connectedness: The starting point for the modern interpretation of autonomy connectedness [4] is that autonomy and connectedness are inherent to each other. The term covers both the capacity to be alone and the capacity to relate to others [3]. Autonomy connectedness developed from the attachment theory [18-20] and was combined with insights from neo-analytical object/relational paradigm [7]. Attachment theory holds that ‘secure’ attachment contributes to the development of autonomy because, under these circumstances, the child can engage in self-exploration. Also mentioned as part of these theories is the importance of separation and individuation, so that the child can learn to differentiate itself from others. In this way, the child learns how to make a distinction between his/her own feelings and those of others. The child breaks away while, at the same time, searching for connection, so that he/she can get feedback and can individualise. The theory of autonomy-connectedness also addresses sex-related differences: it can be demonstrated that there are differences between the way in which men and women sense their autonomy [3]. There are three factors which operationalize autonomy connectedness: a high or low level of sensitivity to others (very sensitive/insensitive to the wishes, opinions and needs of others), women generally having a higher level of focus for others than men [5]. A low level of selfawareness (limited awareness of one’s own wishes, opinions, needs and/or limited ability to express the same in social interaction situations) and a limited capacity to handle new situations (feeling highly stressed and passive in new situations).

Autonomy connectedness and conversion disorders: Recent studies throw greater light on the possible role of insecure attachment, highlighting the dependent and anxious attachment styles in conversion disorders [21]. Trauma and anxious attachment strengthen the link between suggestibility and dissociation [22]. Suggestibility is a property that equates to the extent to which patients are focused on others and are susceptible to directives issued by others. A meta-analysis showed that conversion patients score lower for suggestibility compared with control groups [23]. The focus on others was demonstrated in a study into maladaptive schemas, in which the self-sacrifice schema appeared to be heightened in relation to the norm group [24]. In addition, there are suggestions in the literature that conversion patients have a lower level of self-awareness. The idea is that patients have not learned sufficiently to be aware of signals relayed from the body-referred to in the literature as interoception-and have not learned sufficiently to identify and describe their emotions, also known as alexithymia. In addition, there are indications that conversion patients have a limited sense of agency [25]. Recent research has confirmed the ideas referred to above. Conversion patients appear to have a more limited capacity for interoception and report a higher level of alexithymia compared with other psychiatric patients and the nonpsychiatric group [26,27]. Lastly, research has also been carried out into the extent to which conversion patients are open to new experiences. Patients score lower for openness to new experiences and higher for the avoidance of danger [28,29].

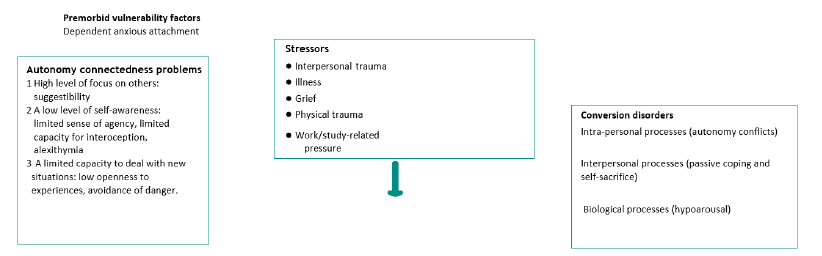

A hypothetical working model for conversion disorders: Our hypothesis is that conversion patients have developed predisposing problems in their autonomy- connectedness. Firstly, they may score higher for the extent to which they focus on others, which fits with a high level of suggestibility. Secondly, conversion patients may score low for their levels of self-awareness, which fits with a reduced capacity for interoception, alexithymia and a limited sense of agency. Thirdly, patients may score low for their capacity to handle new situations. These premorbid factors interact with various stressors that patients experience. Figure 1 shows the stressors that can have a moderating impact on the patient’s stress system from a theoretical viewpoint and can increase the risk of developing a conversion disorder and dissociative symptoms [30,31]. We assume that there are symptoms visible at various levels: intra-personal, inter-personal and biological [32]. After a period of long-term stress, a parasympathetic stress response may arise [33,34] that can insufficiently be regulated by patients. Examples of phenomena and symptoms that we encounter within clinical practice are: conflicts of autonomy, passive coping, selfsacrifice, hypo arousal, coniform disorders such as forgetfulness, and dissociation. Research is necessary to further test and develop this model. The question within this future research will be to what extent the stated predisposing factors, in combination with various stressors, increase the risk of developing a conversion disorder. Once this is clear, clinical practice will be able to consider these premorbid factors in a treatment more focused on the individual, where possible.

Figure 1:Working model for conversion disorders.

Clinical practice

The treatment of premorbid factors in conversion disorders:Various therapeutic treatments that have been developed to address conversion disorders have, over time, evolved further. Psychoanalytical/psychodynamic therapy and cognitive behavioural therapy have extensively described treatment strategies, which we will explain briefly below. Then, we will list the treatment interventions that are specified in the current guidelines, before introducing an intervention to be studied that intervenes on a more emphatic level on the predisposed features that we have covered above.

Psychoanalytical/psychodynamic therapy and cognitive behavioural therapy:Since Charcot studied hysteria, interest in the group of patients presenting with these symptoms has only increased. Initial ideas on the treatment of hysterical personality also arose. Freud & Breuer [4] conceived an intervention that concentrated on the causal affect that was incurred following traumatic experiences (in early childhood). It could not be immediately processed by speaking about the trauma but rather by using an indirect approach, provoking the symptoms via catharsis and then processing them. Breuer used hypnosis techniques to do this. Later, Freud would generally use free association to achieve this. This technique encompasses the instruction to the client to name everything that comes into his or her head. The aim of this was to make patients once again aware of repressed memories. Later psychodynamic treatment strategies focused on the conflict between inner needs/affects that are summoned during interpersonal (traumatic) relationships, and inhibiting factors that prevent patients from accessing these inner needs/affects [35].

The idea expressed by Janet [5] of integrating split (traumatic) aspects has remained in the vanguard of current psychodynamic treatment strategies. Hypnosis and later, catalepsy-induction have been further developed and redesigned within the framework of cognitive behavioural therapy. These treatment strategies departed from Breuer’s original idea to arrive at a cathartic experience and used learning theory principles as the rationale for the explanation of the intervention [36]. The models of Kihlstrom [7] and Edwards et al. [10] were used to explain this. At the centre of this is the idea that indirect control using hypnosis and catalepsy-induction can be accessed during a treatment. For example, this uses permissive suggestions so that patients re-learn how to acquire incompatible movements (for instance a relaxed arm instead of a tense arm). Then previous triggers are provoked using exposure techniques and patients can learn to apply the incompatible movement. Both psychodynamic therapy and cognitive behavioural therapy are included in the current guidelines [4]. In addition, physiotherapy and a multi-disciplinary or inter-disciplinary treatment plan is advised. Other than that, EMDR, schema therapy, psychomotor therapy and virtual-reality treatment may be considered [4].

Autonomy enhancing therapy:Within the group of conversion disorders, psychiatric co-morbidity tends to be the rule rather than the exception. Anxiety disorders and depressive disorders occur frequently within this group [37,38]. In clinical practice we see that comorbid symptoms have a negative impact on the prognosis of conversion disorder [39]. There are also indications that favourable premorbid factors have an influence on a positive result during treatment [40]. There is now evidence to suggest that autonomy enhancing therapy is effective for patients with anxiety and depression-related disorders, as recently shown in a Randomised- Control Trial (RCT). The autonomy enhancing therapy focuses on the three described premorbid factors: high focus on others, low self-awareness and a limited capacity to deal with new situations. Our hypothesis is that a treatment that is specifically focused on the described premorbid factors may contribute to recovery from both the conversion disorder and the comorbid anxiety and depression-related complaints. The hypothesis also states that autonomy enhancing therapy may contribute to a more enduring and effective treatment. The symptoms are bio-psychosocially ‘translated’ within this intervention as a (physical) survival strategy that can manifest itself due to premorbid vulnerability factors in combination with stressors that are experienced. By interpreting the complaint as a survival strategy, it is possible to make a start on boosting the patient’s capacity for self-management. The patient learns to understand his/her symptoms within the context of his/ her personality and learning history. In this way it is possible to generate a different narrative for the patient, because of which he/she can learn to have a new relationship with the body [38]. Through focused mindfulness and ‘body mentalization’, the patient can develop a sense of self-awareness. In addition, within the autonomy enhancing therapy, coping capabilities can be learnt in terms of setting boundaries and communicating. Topics such as physical experience, intimacy and sexuality are discussed during treatment sessions, as a result of which the patient learns to experience these topics and learns to talk about them. The patient is made aware of emotional and cognitive experiences and ultimately, the experiences are linked to friendships and relationships, and a plan to prevent relapse is drawn up.

Example of successful therapy:Romy (35) has been having problems for the past few years with tremors and instances of paralysis in her arms. These symptoms developed in the aftermath of an accident, in which she was thrown from her bike onto the back of a car, crashing through the rear window and landing on the driver’s seat. She broke her arm and after a period of rehabilitation, regained full functionality in the arm. However, five months later she started suffering recurring tremors, sometimes even losing feeling in both arms for days on end. This troubled the people around her and on the insistence of others, she sought help from the neurologist, who examined her at length and ascertained that the movements were incompatible with a neurological disorder. The sense of powerlessness that Romy’s friends and family felt only grew and in consultation with the neurologist, she sought help in the form of psychology and physiotherapy.

The psychologist was struck by the way in which Romy told the story of her life. Romy said that she had not really been frightened in any way by the accident and did not feel anxious about the episodes of paralysis in her arms, for example. While she was telling the story, the lack of emotion in her voice was also noticeable. She had lost her father at the age of eleven and had never spoken about the impact that had had on her. Her mother and younger brother could hardly grasp this loss, but the family had found a way to survive by not talking about the experience and carrying on as normal. Romy’s mother had always had a big influence on her. Romy described her as someone who wanted to prevent anything that could go wrong from going wrong, wherever possible. Her mother often predicted the scenarios in which things could go wrong and for example, took on the homework that Romy needed to finish for school, so that she wouldn’t forget it. In her mother’s words, setbacks had to be avoided wherever possible. Romy taught herself to adapt to her mother’s ways, and this took on even greater proportions after her father’s death. Romy started to doubt whether she would be able to finish school, although in the end she achieved this relatively easily. It also took a relatively long time for her to leave the family home and live independently. When she finally left, she kept herself to herself and did not actively seek out new social contacts. She felt guilty, as if by leaving the parental home she had deserted her mother. Her mother was left alone in the house. Cycling was her real hobby, and she could cycle for hours at a time through the forest, until the point at which she had the accident. After that, Romy could only focus on recovering and going into rehabilitation as quickly as possible. Once she had recovered, she felt flat and empty for a time. The tremors and paralysis developed gradually. The period of hospitalisation during which she was examined by the neurologist was something that generally passed her by. Others began to express their concern and on their insistence, she decided to seek help. Initially she went to a physiotherapist, then to a psychologist as well. The psychologist discussed the diagnosis of conversion disorder with her and explained that her ability to manage her own body had sustained a blow after the accident. Apart from that, the psychologist talked about how previous experiences, personality traits and the stressors that she had had to contend with had probably played an important role in the recurrence of the symptoms. An excessive focus on others and too little focus on her own body played a role in this and in addition, a low openness to new experiences played a significant perpetuating role. The aim of the therapy was to teach herself to focus more on the signals her own body was sending her, her needs and awareness of the emotions she was experiencing. The conversion disorder was something that Romy interpreted as a way of her body telling her that she was going beyond her boundaries. She focused on her own body and she began to understand what her body was trying to tell her when the symptoms manifested themselves. In this way, Romy taught herself to take control and was able to sense when she was going beyond her (physical) boundaries and when it was time to stop. Then she learnt to put what she was feeling into words more easily. She also learnt to talk about the impact of the loss of her father in relation to her life and the physical impact of having had an accident. In this respect she became gradually better at recognising the signals of anxiety in her body. She also learnt to talk about intimacy and felt what was okay and what was not in relation to her body. The awareness of her physical senses continued to increase. During therapy sessions, Romy regained confidence in her body and was able to use it to provide information on what she herself wanted, rather than what other people wanted. One consequence of this was that she went in search of new situations and felt she was once again able to do things. She started cycling again and began engaging in social situations. She joined a mountain bike club. The tremors and paralysis never came back and faded into the background as far as Romy was concerned.

Conclusion

Where Charcot (1850) dabbled with neurological explanations for hysteria and ended up having a hunch that psychological explanations might point to a solution for the problem, it is nonetheless still unclear what roles are played by somatic and the psyche in conversion disorders. Despite there being more awareness for a bio-psychosocial model and the fact that the etiology is interpreted differently, from a multi-factorial model, premorbid factors are still not being considered enough, although this could offer an opportunity for a more sustainable and effective treatment. This article is an attempt to reveal a hypothetical working model which gives sufficient weight to premorbid and sustaining factors in conversion disorders. Further research is necessary to test this model, so that this may, in future, be used for a more focused and sustainable treatment.

Learning objectives

After reading this article, you will:

A. Be aware of the different explanations for the development

of a conversion disorder.

B. know more about a new, hypothetical working model

from which conversion disorder may be understood.

C. Be familiar with a new treatment strategy ripe for research

that can be used for patients with conversion disorders.

D. Be able to use the knowledge presented in this article

to reflect on the importance of weighing up and considering

premorbid factors in the treatment of conversion disorders.

References

- Gilson F (2010) Hysteria according to Charcot. The rise and disappearance of the nervous disorder of the century: A medical historical study. Magazine Psychiatr 52(12): 813-823.

- Charcot JM (2013) Clinical lectures on diseases of the nervous system (Psychology Revivals). 1st (edn), Oxfordshire: Routledge, Southeast England, UK.

- Stone J, Smyth R, Carson A, Warlow C, Sharpe M, et al. (2006) La belle indifference in conversion symptoms and hysteria: Systematic review. British Journal of Psychiatry 188: 204-209.

- Freud S, Breuer J (1895) Studies on hysteria. Dutch Edition, Clinical Considerations, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

- Janet P (1977) The mental state of hystericals. In: Robinson DN, Corson CR (Eds.), Significant Contributions to the History of Psychology, Series C, Medical Psychology, University Publications of America, Washington DC, USA.

- Jones E, Fear NT, Wessely S (2007) Shell shock and mild traumatic brain injury: A historical review. American Journal of Psychiatry 164(11): 1641-1645.

- Kihlstrom JF (1992) Dissociative and conversion disorders. In: Stein DJ, Young JE (Eds.), Cognitive science and clinical disorders, Academic Press, Orlando, Florida, USA, pp. 247-270.

- Ludwig L, Pasman JA, Nicholson T, Aybek S, David AS, et al. (2018) Stressful life events and maltreatment in conversion (functional neurological) disorder: Systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Lancet Psychiatry 5(4): 307-320.

- Gold SN, Ketchman SA, Zucker I, Cott MA, Sellers AH, et al. (2008) Relationship between dissociative and medically unexplained symptoms in men and women reporting childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Family Violence 23(7): 596-575.

- Edwards MJ, Adams RA, Brown H, Parées I, Friston KJ, et al. (2012) A Bayesian account of hysteria. Brain 135(pt 11): 3495-3512.

- Pick S, Rojas-Aguiluz M, Butler M, Mulrenan H, Nicholson TR, et al. (2020) Dissociation and interoception in functional neurological disorder. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry 25(4): 294-311.

- Ricciardi L, Demartini B, Crucianelli L, Krahé C, Edwards MJ, et al. (2016) Interoceptive awareness in patients with functional neurological symptoms. Biological Psychology 113: 68-74.

- Williams IA, Reuber M, Levita L (2021) Interoception and stress in patients with functional neurological symptom disorder. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry 26(2): 75-94.

- Woud ML, Zhang XC, Becker ES, Zlomusica A, Margraf J, et al. (2016) Catastrophizing misinterpretations predict somatoform-related symptoms and new onsets of somatoform disorders. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 81: 31-37.

- Nahab FB, Kundu P, Maurer C, Shen Q, Hallett M, et al. (2017) Impaired sense of agency in functional movement disorders: An fMRI study. PloS one 12(4): e0172502.

- Wachter D (2007) Misconception: The treatment of dissociative disorders should focus on processing past traumatic events. DITH 27: 169.

- Fobian AD, Elliott LA (2019) Review of functional neurological symptom disorder etiology and the integrated etiological summary model. Journal of Psychiatry Neuroscience 44(1): 8-18.

- Bekker MH, Assen MA (2006) A short form of the autonomy scale: Properties of the autonomy-connectedness scale. J Per Assess 86(1): 51-60.

- Bekker MH, Assen MA (2017) Autonomy-connectedness mediates sex differences in symptoms of psychopathology. PloS one 12(8): e0181626.

- Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall SN (1978) Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. 1st (edn), Psychology Press, New York, USA.

- Bekker MH (2022) Autonomy-attachment: Transdiagnostic factor and target for recovery. Journal of Psychotherapy 48: 349-361.

- Bowlby J (1969) Attachment and loss volume 1: Attachment. 2nd (edn), Basic Books, New York, USA.

- Chodorow N (1989) Feminism and psychoanalytic theory. Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

- Bekker MH, Assen MA (2008) Autonomy-connectedness and gender. Sex Roles 59: 532-544.

- Yasin A, Ashraf MR (2019) Attachment styles and interpersonal problems in patients with conversion disorder. European Journal of Research in Social Sciences 7(1): 27-35.

- Wieder L, Terhune DB (2019) Trauma and anxious attachment influence the relationship between suggestibility and dissociation: A moderated-moderation analysis. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry 24(3): 191-207.

- Wieder L, Brown R, Thompson T, Terhune DB (2021) Suggestibility in functional neurological disorder: A meta-analysis. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry 92(2): 150-157.

- Stroink L, Mens E, Ooms MH, Visser S (2022) Maladaptive schemas of patients with functional neurological symptom disorder. Clinical Psychology Psychotherapy 29(3): 933-940.

- Demartini B, Petrochilos P, Ricciardi L, Price G, Edwards MJ, et al. (2014) The role of alexithymia in the development of functional motor symptoms (conversion disorder). Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery Psychiatry 85(10): 1132-1137.

- Dimaro LV, Dawson DL, Roberts NA, Brown I, Moghaddam NG, et al. (2014) Anxiety and avoidance in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: The role of implicit and explicit anxiety. Epilepsy Behavior 33: 77-86.

- Sarisoy G, Kaçar ÖF, Öztürk A, Yilman T, Mor S, et al. (2015) Temperament and character traits in patients with conversion disorder and their relations with dissociation. Psychiatry Danub 27(4): 390-396.

- Pietromonaco P, Beck LM (2019) Adult attachment and physical health. Current Opinion in Psychology 25: 115-120.

- Schauer M, Elbert T (2015) Dissociation following traumatic stress. Journal of Psychology 218(2): 109-127.

- Testa SM, Krauss GL, Lesser RP, Brandt J (2012) Stressful life event appraisal and coping in patients with psychogenic seizures and those with epilepsy. Seizure 21(4): 282-287.

- Luyten P (2016) Dynamic Interpersonal Therapy (DIT). Journal for Psychoanalysis 21: 264-273.

- Kleine R, Hoogduin K, Minnen A Van (2011) Protocol treatment of patients with motor conversion disorder: Hypnosis and catalepsy. Directive Therapy 31: 153-208.

- Pehlivantürk B, Unal F (2002) Conversion disorder in children and adolescents: A 4-year follow-up study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 52(4): 187-191.

- Şar V, Akyüz G, Kundakçı T, Kızıltan E, Doğan O, et al. (2004) Childhood trauma, dissociation and psychiatric comorbidity in patients with conversion disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 161(12): 2271-2276.

- Leary PM (2003) Conversion disorder in childhood-diagnosed too late, investigated too much? Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 96(9): 436-438.

- Kunst LE, Maas J, Balkom AJ, Assen MAV, Kouwenhoven B, et al. (2022) Group autonomy enhancing treatment versus cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: A cluster randomized clinical trial. Randomized Controlled Trial 39(2): 134-146.

© 2023 Luuk Stroink, This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)