- Submissions

Full Text

Psychology and Psychotherapy: Research Studys

Physician Stress, Burnout, Disenchantment and Undesirable Behaviors: What Can We Do?

Rosenstein AH*

Practicing Internist and Consultant in Physician Behavioral Management, USA

*Corresponding author: Rosenstein AH, Practicing Internist and Consultant in Physician Behavioral Management, USA

Submission: November 14, 2022Published: March 02, 2023

ISSN 2639-0612Volume6 Issue3

Abstract

Growing stress and burnout has intensified negative physician thoughts and feelings about medical practice. Working under increasing pressures from outside interference, time spent on fulfilling nonclinical bureaucratic demands, growing complexity and new technology innovations, requirements for electronic medical record documentation, increasing productivity and capacity requirements, and workflow changes have all impacted physician attitudes and behaviors toward the delivery of medical care. As a result, many physicians have either left practice prematurely or tried a variety of practice readjustments. Many of those who stay are unhappy or dissatisfied with their positions. Some suffer from physical or emotional harm. Others become aloof, angry, and cynical. Some express their frustrations by exhibiting disruptive behaviors which negatively impact work relationships and can impede quality care. Organizations need to recognize the cause and consequences of this stressful environment and provide resources to help physicians better adjust to the pressures of medical practice

Keywords:Physician stress and burnout; Disruptive behavior; Physician wellness

Introduction

It’s a stressful road becoming a physician. It takes years of dedicated study in a highly competitive market just to get into medical school. Then there’s the less than friendly training environment that requires intense dedication and commitment that leads to physical and mental exhaustion. A number of recent studies have documented the toll of stress and burnout on medical trainees with suggestions of how organizations can provide support to help those in need [1]. Most of us get through it with the idea of following our calling to help others in need. The next phase is entry into medical practice. Many years ago physicians practiced independently or joined small medical groups where they could deliver their services as they felt appropriate without any outside intrusion or intervention. Then in the late 1900s the introduction of managed care and utilization controls inhibited physician autonomy, authority and control. Physicians were not happy with these changes but for the most part they accepted their role as they were still able to continue to apply their craft. The early 2000s ushered in the era of value-based care, the electronic medical record, and cost/ quality metric based performance accountability all of which changed the landscape to a point where many physicians decided to migrate into employed positions. Despite a growing emphasis on productivity and efficiency, most physicians were able to weather the storm. The stress was there, but it was manageable and accepted as a cost of doing business.

The pandemic was the final straw. Issues around access, protection, limited resources, and changing care management priorities put even more pressure on physicians to the point that they felt that they weren’t appreciated and began to question purpose and the value of what they were doing. Stress and burnout levels were at an all-time high affecting over 60% of physicians. Nearly one quarter of physicians reported symptoms of clinical depression [2]. This led to what is described as the “mass resignation”, a serious issue in the face of a looming physician manpower shortage [3]. We need to look at physicians (and all clinical staff) as an over worked, overburdened, precious limited resource and do what we can to help them survive and succeed in today’s chaotic medical environment [4]. Actions need to be taken to help physicians in distress and manage those physicians who act inappropriately. We can’t look to the physicians themselves to make the necessary adjustments and need to depend on their organization or other outside resources to help with this problem.

Factors affecting physician behavior

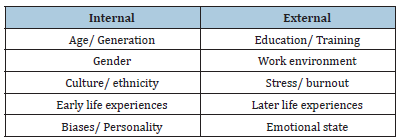

There are a multitude of factors that contribute to shaping the values, thoughts, and perceptions that influence individual attitudes, biases, and behaviors (Table 1). The internal factors are deep seated experiences related to a person’s age and generation, gender and sexual identity, culture, ethnicity, and spirituality, and early life events that help shape one’s values, biases, and personality. There are a number of different approaches that can be taken to address internal issues. Issues related to different values based on age and generation preferences (Baby Boomers/ Generation X) can be discussed through educational programs that highlight generational preferences in regard to work ethic, use of technology, and communication styles. Gender related issues can be addressed by gaining a better understanding of male/ female characteristics and preferences and sexual harassment programs. Sexual identity issues can be addressed through LGBT awareness and education programs. Culture and ethnicity issues can be addressed through diversity or cultural competence training programs. More deepseated issues can be addressed through more individualized behavioral counseling/ therapy programs.

Table 1:Factors affecting attitudes and behaviors.

One of the key contributing factors is the role of emotional

intelligence and the influence of subconscious implicit bias.

Emotional Intelligence is akin to social awareness. It’s a four phase

process that includes

A. self-awareness on one’s own values, biases, and

perceptions that affect individual behaviors

B. social awareness of the values, needs, and perceptions of

those that you are dealing with

C. management and control of individual reactions to

maximize desired results

D. how to optimize relationship management and

communication to reach an outcome that meets individual

needs by clarifying goals and expectations [5].

One of the driving forces behand emotional intelligence is the influence of underlying biases [6]. There are many types of subconscious implicit biases that can be lumped under the umbrella of cognitive bias. Cognitive bias is defined as the tendency for people’s feelings and experiences to affect their judgment. This is a crucial issue in healthcare as there have been many recent studies documenting the significant influence of implicit bias in patient relationships [7]. Issues related to appearance, weight, age, income, race, language, educational level, and sexual identity all impact physician biases and need to be considered when trying to manage prejudicial behavioral tendencies [8]. The external factors include education and training, work environment, stress and burnout, and later life experiences. The external factors are more amenable to intervention. It is well recognized that the medical training arena is harsh and demanding. There are many studies documenting the ill effects of overwork and fatigue and the resulting stress and pressure placed on trainees [1,9]. Many organizations are beginning to recognize the serious impact of stress and depression and have made a much stronger effort to provide appropriate mental health support and address stigma and other barriers that inhibit action [10]. The work environment, stress, and burnout are key issues and will be discussed in the next section.

Stress and burnout

For the physician working under stress and pressure is nothing new. It was an accepted obligation of medical practice. A landmark study published in the Mayo Clinic Proceedings was the first comprehensive survey that documented the prevalence and seriousness of this condition. They looked at stress and burnout rate by individual specialty. The overall rate was above 50% across all specialties [11]. This was a wakeup call for action. A repeat study four years later showed no improvement [12]. In the most recent study from the Mayo Clinic the stress and burnout rate increased to 60% [13]. Ongoing surveys published by Medscape also reported physician burnout rates as high as 60%, and clinical depression rates above 25% [2]. There were also noted increases in substance abuse and suicidal ideation. Stress, burnout, depression, and dissatisfaction has a significant impact on attitudes and behaviors that affect medical practice.

Addressing stress and burnout: Causes and consequences

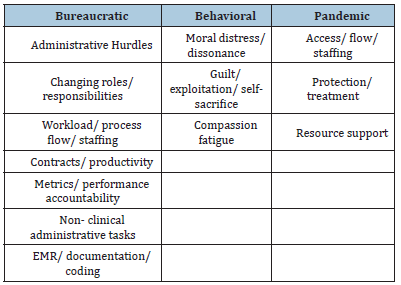

Table 2 outlines a number of factors contributing to physician stress. Most of these factors are system wide issues that include a growing list of required administrative tasks, less time for direct patient care, changes in staffing, process flow, roles, and responsibilities, metric based performance outcome accountability, issues related to capacity and demand, and requirements for electronic medical record documentation and coding. Behavioral tendencies include moral distress and dissonance resulting from not being able to do what they want to do, exploitation by taking advantage of individual passion and willingness to self- sacrifice, and day to day frustrations leading to compassion fatigue and exhaustion [14-16]. The pandemic has accentuated problems related to changes in patient access and flow, treatment, and resource availability [17]. The consequences are increasing stress, burnout, and depression, a sense of loss of purpose and meaning, apathy and detachment, and inappropriate behaviors affecting care relationships.

Table 2: Causes of stress and burnout

Addressing stress and burnout: Treatment

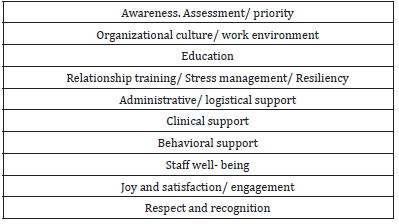

This is a complex issue and there is no one solution or quick fix. Table 3 gives an outline of recommended strategies. A successful approach must include both individual and organizational readjustments. The first recommendation is to raise levels of awareness as to the prevalence and significance of working under high stress conditions. Assessments can be made informally through group discussions or town hall events, or more formally through designed survey assessment tools such as the Maslach, Mini Z or Proqol instruments. The organization needs to be able to respond to staff concerns and recognize the importance of strong leadership endorsement and presence in establishing an empathetic supportive work culture. Dedicated programs on stress management, conflict management, resiliency, and/or mindfulness training can help provide strategies for stress reduction. Additional staff education and training may be needed to enhance communication, team collaboration, and care relationship skills. All these strategies focus more on the individual’s adaptation to stress and burnout. The problem is that over 80% of the causes need a system fix rather than an individual adaptation approach [18-20].

Table 3: Addressing stress and burnout

Reducing the clinician’s logistic burden by adjusting scheduling, capacity, and productivity requirements will help lighten their load. Reducing on-call or committee responsibilities will free up more time for clinical care. Providing support for electronic medical record entry and documentation through individualized training or through the use of scribes will help lower physician concerns about electronic data entry. Using Physician Assistants or Nurse Practitioners for routine care will free up time for the physician to concentrate on more complex patient care issues. Behavioral support can be provided through informal conversations or facilitated town hall or group discussions. More individualized support can be provided through Physician Wellness Committees, contracted Physician EAPs (Employee Assistance Programs), coaching and mentoring programs, or targeted counseling or therapeutic services depending on the underlying condition. There needs to be an overriding emphasis on improving overall staff wellbeing by enforcing time off for rest and relaxation [21]. We need to remind physicians about what they do and return the joy and pride of being a doctor [22,23]. Give them an opportunity to be heard, recognize and respond to their concerns. Happier, more content, more satisfied physicians are more engaged and have a lower likelihood of acting in an inappropriate manner. Show compassion and respect and make a special effort to thank them and recognize them for all that they do.

Managing inappropriate/disruptive behaviors

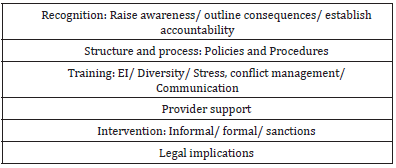

Disruptive behavior is defined as any inappropriate behavior that can negatively impact care relationships and potentially compromise patient safety and quality of care [24]. Despite the fact that many organizations are taking steps to reduce the incidence of disruptive events they continue to occur at alarming rates [25,26]. There is a growing amount of evidence that the recent stress, burnout, and depression accentuated by the pandemic have increased the likelihood of disruptive events [27]. With growing care complexity across the full spectrum of care, changes in process and flow, and growing staff and resource shortages, it’s more important than ever to address this issue in an effective manner. The focus needs to be on the importance of developing an effective well-coordinated team endorsed patient care relationship. Table 4 gives a listing of recommended approaches to this problem.

Table 4: Reducing the incidence of disruptive behaviors

The first step in the process is to raise awareness as to the significance of the problem. Individuals need to recognize the potential downstream adverse events affecting patient safety, quality, satisfaction, and overall morale [28]. Individuals need to be held accountable for their actions. There needs be a Disruptive Behavior Policy in place (a Joint Commission Standard) which requires a definition and follow through actions, interventions, and repercussions for repetitive disruptive behaviors. There needs to be a consistent confidential incident reporting system which provides follow through on registered complaints. There needs to be a zerotolerance policy that combats the resistance to look the other way particularly if it involves a high volume high profit admitter. Depending on the specifics, additional training and education in Emotional Intelligence, diversity and cultural competency, sexual harassment, anger, stress, and conflict management, and improving communication and team collaboration skills will enhance care relationships and the overall patient experience. For those in need the organization should provide appropriate behavioral support utilizing coaching, counseling, or tailored behavioral therapy in an effort to improve behaviors.

Each incident needs to be evaluated. The first step is the informal coffee time conversation. Take the physician aside to a neutral space and discuss the observations. Most of the time the physician didn’t realize that their actions were construed in such a manner and easily made the adjustments to prevent this from happening again. For repeated offenders, and in particular when they can see no wrongdoing, there needs to be a more formal intervention. After due diligence, skilled representatives need to meet with the physician, discuss the behaviors in question, and make recommendations for improvement. In order to prevent potential restrictions or sanctions, the physician needs to understand and agree to the terms and provide documentation of follow up actions. In more extreme cases the physicians may be referred to the specialty programs provided by Vanderbilt or PACE (San Diego) programs. Failure to comply can result in not recredentialing, loss of privileges, sanctions, or termination [29]. As an expert witness in this area, when it gets to the restriction of privileges stage, it is crucially important for the organization to follow due process, document all the incidents and concerns, and make appropriate recommendations for next steps. The primary focus is to help the physician and protect patient and staff safety, quality, satisfaction, and morale. Final decisions are made by the Executive Committee and Board actions.

Conclusion

Physicians (and all clinical staff) are a precious limited resources and we need to do everything that we can to keep them going and better adjust to the stress and pressures of medical practice [30]. Growing stress and burnout have put increasing pressure on physicians leading to unwanted physical and emotional turmoil. Most physicians try to deal with this on their own. Some physicians have changed jobs. Others have sought early retirement. For those who remain we worry about their well-being and their ability to continue to practice in an effective productive manner. In some individuals the situation can provoke unprofessional disruptive behaviors. We need to do what we can to prevent these types of events from occurring utilization some the recommendations made above, Persistent abusers need to be dealt with. We can make recommendations for help and hope this will do some good. For the few who continue to exhibit a disturbing pattern of disruptive behaviors the organization needs to be willing to make the appropriate recommendations to curtail these events and protect patients and staff from harm.

References

- Zhou A, Panagioti M, Esmail A, Agius R, Tongeren MV, et al. (2020) Factors associated with burnout and stress in trainee physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open 3(8): e2013761.

- (2023) Medscape burnout and depression 2023 survey.

- Abbasi J (2022) Pushed to their limits, 1 in 5 physicians intends to leave practice. JAMA 327(15): 1435-1437.

- Rosenstein A (2020) Helping physicians survive the mental chaos of medical practice. Austin Journal of Psychiatry and Mental Disorders 5(2): 1025.

- Rosenstein A, Stark D (2015) Emotional intelligence: A critical tool to understand and improve behaviors that impact patient care. Journal of Psychology and Clinical Psychiatry 2(1): 1-4.

- Sabin J (2022) Tackling implicit bias in health care? New England Journal of Medicine 387(2): 105-107.

- Heath S (2022) Implicit bias is still a hallmark of patient experience. Patient Engagement HIT, Massachusetts, USA.

- LeBrun N (2021) Avoid these 7 common doctor biases about patients. Health grades for professionals, Denver, USA.

- Dyrbye L, West C, Satele D, Boone S, tan L, et al. (2014) Burnout amongst US medical students residents and early career physicians relative to the general US population. Academic Medicine 89(3): 443-451.

- Mock J (2021) How to make resident mental health stigma free. The Hospitalist, USA.

- Shanafelt D, Hasan O, Dyrbye L, Sinsky C, Satele D, et al. (2016) Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general us working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 90(12): 1600-1613.

- Shanafelt T, West C, Sinsky C, Trockel M (2019) Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general us working population between 2011 and 2017. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 94(9): 1681-1694.

- Shanafelt D, West C, Dyrbye L, Trockel M, Tutty M, et al. (2022) Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work- life integration in physicians during the first 2 years of the covid-19 pandemic. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 97(12): 2248-2258.

- Agarwal S, Pabo E, Rozenblum R, Sherritt KM (2020) Professional dissonance and burnout in primary care: A quantitative study. JAMA Intern Med 180(3): 395-401.

- Blum L (2019) Physician’s goodness and guilt-emotional challenges in practicing medicine. JAMA Intern Med 179(5): 607-608.

- Sexton B, Adair K, Proulx J, Cui K, Profit J, et al. (2022) Emotional exhaustion among us healthcare workers before and after the covid-19 pandemic, 2019-2021. JAMA Network Open 5(9): e2232748.

- Schechter A, Norful A (2022) A peri pandemic examination of health care worker burnout and implications for clinical practice, education and research. JAMA Network Open 5(9): e2232757.

- Rosenstein A (2021) Organizational Vs individual efforts to help manage stress and burnout in healthcare professionals. Nursing and Healthcare 6(1): 11-13.

- Goroll A (2020) Addressing burnout-focus on systems, not resilience. JAMA Network Open 3(7): e209524.

- Praslova L (2023) Today’s most critical workforce challenges are about systems. Harvard Business Review, Massachusetts, USA.

- Murthy V (2022) Confronting heath worker burnout and well-being. N Engl J M 387(7): 577-579.

- Dugdale L (2017) Re-enchanting medicine. JAMA Internal Medicine 177(8): 1075-1076.

- Rosenstein A (2022) Can we still enjoy being a physician? Journal of Community and Preventive Medicine 3(2): 9.

- Rosenstein A, O Daniel M (2008) A survey of the impact of disruptive behaviors and communication defects on patient safety. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety 34(8): 464-471.

- Rosenstein A (2015) Physician disruptive behaviors: Five year progress report. World Journal of Clinical Cases 3(11): 930-934.

- Whyte J, Ramsay D (2022) Physicians behaving badly: Stress and hardship trigger misconduct. Medscape Internal Medicine, USA.

- Rosenstein A (2023) The link between physician stress, burnout and disruptive behaviors. Journal of Medical Practice Management 38(4): 163-166.

- Rosenstein A (2011) The economic impact of disruptive behaviors: The risks of non-effective intervention. American Journal of Medical Quality 26(5): 372-379.

- Rosenstein A, Karwaki T, Smith K (2016) Legal process and outcome success in addressing disruptive behaviors: Getting it right. Physician Leadership Journal 3(3): 46-51.

- Rosenstein A (2019) Hospital administration response to physician stress and burnout. Hospital Practice 47(5): 217-220.

© 2023 Rosenstein AH, This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)