- Submissions

Full Text

Psychology and Psychotherapy: Research Studys

Sculpting Space: Reflections on How Spaces Affect Social Performance and Health

Bernie Warren1* and Glenys McQueen Fuentes2

1SODA University of Windsor, Canada

2Brock University, Canada

*Corresponding author: Bernie Warren, SODA University of Windsor, Canada

Submission: May 24, 2022Published: June 06, 2022

ISSN 2639-0612Volume5 Issue5

Abstract

a. This paper explores how space affects social performance and by extension the perceived

health of the individual performing within it.

b. It examines some of the ways that:

i. individuals’ perspectives and perceptions affect the space in which we each perform.

ii. the nature of the space(s) on which we perform affect how we the perform in social contexts

with a particular emphasis on Taoist notions of Chi(energy), Feng Shui, Double Balance, & Dance

Towards Wellness.

iii. understanding the therapeutic and theatrical nature of space may help educators and clinicians

enable their students and clients to manage their daily social interactions more effectively.

Keywords:Social performance; Space; Energy; Taoism; Feng shui; Therapeutic space; Mental health

Introduction

In this article we explore space from both an eastern perspective, notably Taoist [1], and a western perspective, both theatrical and therapeutic. We examine some of the reciprocal ways that spaces affect our social performances, and by extension how we are perceived by others. We examine how understanding our interactions in different spaces, theatrical and social, may help both individual social actors and therapists in their practice. We focus primarily on dance-movement, an integral part of human performance and the therapeutic applications of drama. One final point this article should not be considered an academic research paper but rather personal reflections, our own perspective, based on our more than eighty years of praxis.

Feng shui, world maps and performance space

Successful human performance in any situation requires an awareness of space and the needs of each scene to be performed upon it. For several years I (BW) was an actor/dancer in touring theatrical performances. During this time, I performed in pub courtyards, shopping malls, school gyms, maximum security prisons, on village greens, and theatre stages. No matter where the performance took place, I always walked the space before any performance to get a sense not only of the dimensions and acoustics of the space, but also to get a feel of the energy within it. For the Feng Shui [2] of each space exerts an influence on each performance. For all spaces, even empty spaces, are alive and full of possibilities. As Berger suggests, what we see situates us within our surrounding world [3]. If asked, we can describe and explain our world with words, but as Korzybski pointed out the word is not the thing it describes [4]. So, even though we hear the sounds, feel the heat/cold, and the energy of each space, irrespective of whether it is the verdant landscapes of the countryside or the imposing architecture of a major city, we may not be able to adequately convey our responses to what we experience.

Spaces speak to each of us in different ways and create sensations within us, as we respond to the energy and feel of each space. We have a visceral, a psycho-somatic, response to the space in which we exist. Yet how we each respond to any space is affected by what we each have experienced before we entered that space. Our genetics, our social upbringing and past social experiences are the lens through which we encounter and perceive each new space. David Gordon expanded on NLP (Neuro-linguistic programming) theories to discuss how each of us creates, from a multitude of factors, a personal World Map as a lens through which we interact with the stimuli we encounter in our day-to-day experience [5,6]. Our World Map is built upon our individual life experiences within the cultural matrices in which we experienced them. It gives each of us a sense of our place in the world and provides the framework for our beliefs and prejudices. While it may be transformed with experiences over time, it also frames the way we experience each space.

Blinded by the light-some factors that influence our perspective

Our perceptions of space affect how we see, construct, and respond to our world. Nine months ago, I (BW) retired and moved to my current abode. A lovely corner apartment on the top (6th) floor. Every day I engage in my morning Qigong, martial arts, and Yoga practice on our balcony when weather is good enough, or indoors if not. While doing my practice, I play tranquil music, listen to the bird song, and soak up the stunning views of Lake Erie and the many trees, the remains of an old growth Carolinian forest, that are between my building and the water. This was a very welcome change, as for the previous five years I had practiced on a back balcony above a realtors’ office looking at rundown buildings and a back alley peopled with ‘sketchy’ characters

Recently, I became aware of how the view from my balcony changes almost every day, depending on a multitude of variables. The most obvious is the light which is affected by the time of day, the month of the year and the weather. Simply standing there breathing and performing my daily practice I became aware that our perception of any space is changed by factors beyond our control that transform the way we experience that space. In the case in point, the energy on my balcony is transformed by environmental factors which in turn affect how I feel when pursuing the repetitive movements of my daily martial arts, qigong, and yoga practice.

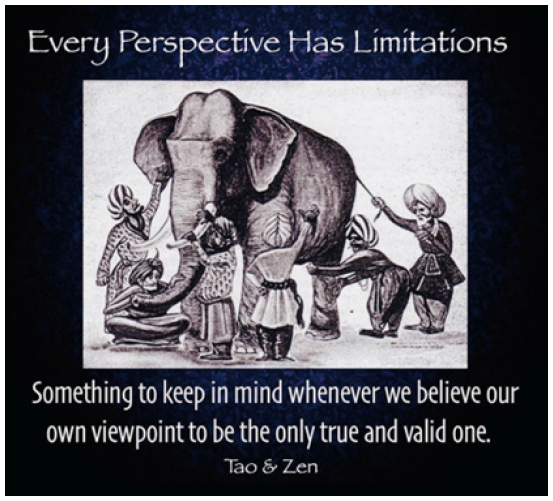

Fable of the wise blind men and an elephant

The parable of the Blind Men and an Elephant, which probably originated in ancient India, may be found in many religious traditions, texts, and lore most notably Buddhist, Hindu, Jain, and Sufi. It is a story of a group of blind men who have never come across an elephant before and who learn to conceptualize what the elephant is like by touching it (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Perspective has its limits [6].

Each blind man feels a different part of the elephant’s body, but only one part, such as the side or the tusk. They then describe the elephant based on their limited experience. Their descriptions of the elephant are different one from another. In some versions, each comes to suspect that the others are dishonest, and they come to blows. The moral of the parable is that humans tend to claim absolute truth based on their limited, subjective experience as they ignore other people’s limited, subjective experiences, which may be equally true.

Exploring points of view-brecht’s street scene adapted

Recently, I (BW) started to use an adapted version of Brecht’s Street scene [7] to help teach how perspective affects an individual’s point of view. This exercise has been delivered successfully both in traditional and virtual classrooms in many different countries around the world (e.g., Canada, Thailand, India, China, Spain) [8].

In this exercise, a crossroads with traffic lights is drawn on the

board.

i. The facilitator, together with the participants decide what

is to be found at each corner e.g. a particular shop, a bar, a car park,

a bank.

ii. Each participant without telling anyone else chooses why

they are at that location, and at which corner they are standing.

iii. The facilitator then draws on the board an accident

between a car and a motorcyclist in the middle of the crossroads.

The motorcyclist is lying on the ground covered in blood and the

driver and passengers are beside the car looking at the motorcyclist.

a. It is made clear that participants have no emotional

attachment to the people involved in the accident.

iv. Participants are then asked to close their eyes and

visualize seeing the accident happen from where they are standing.

a. They are asked to replay the scene in their head and write

what they saw from their chosen perspective

b. After this they are asked to identify who was to blame for

the accident.

c. Next through a series of discussions and improvisations

participants examine the accident from different perspectives and

questions are asked:

d. How does where you are standing influence how you see

the accident?

e. Would your view of ‘blame’ be influenced if one of those

involved in the accident is:

a) A health worker?

b) A celebrity?

c) A Priest/Iman/Rabbi?

d) A member of your immediate family?

Other questions that can be explored include:

a. What would happen if the accident happened in a different

country?

b. How would different cultures react to a woman or a male

driver?

Discussion often revolves around the fact that decisions are made based on knowledge, intuition, and how different perspectives change our view of events. This exercise is full of rich, exciting ways of getting into a multitude of possible areas of exploration from character to culture to clothing to angles both literally and metaphorically of people, objects, surroundings, etc. It can also lead to discussion of the work of Adam Kahane [8]. His central question, how can we work together to solve the problems we have created together? and his innovative solutions, where there is not one outcome expected but where everyone despite differing needs may come away satisfied - we feel is of great significance to educators and therapists alike.

Taoist views on space, energy, and health

For the Taoist the universe is alive with a kind of primal power, a force they refer to as Chi [9]. Taoist belief suggests that not only do all living things possess Chi but also that, we all live within this vital force. Taoists believe, as do many physicists, that at the simplest level all life is pure energy. In Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chi is said to flow through 12 primary and 8 collateral meridians within the body and blockage of the flow of energy through these meridians is believed to be the major causes of ill health. One of the most important aspects of the Taoist conception of well-being is that to remain healthy we must constantly regulate our actions, and thus our Chi, to remain in balance within ourselves and with the external and ever-changing universe. Taoist healers believe that the correct balance between Yin and Yang (opposite and complementary forces such as day and night, female, and male) and the harmonious mixture of the five elements (Earth, Fire, Metal, Water, Air) cause health: that the relative harmony of tendencies and forces within an individual IS the individual’s state of health. They contend that the opposite is also true, that lack of balance and disharmony cause disease [10].

The essence of Taoist healing is to strike a double balance. Not only should the energies of the body be in balance with themselves, but the body must itself be in harmony with its surroundings, the space in which it exists. Moreover, the Taoist healer is a part of the process of healing. This is the ultimate holistic perspective. Body, mind, and spirit are a unity and so are patient and practitioner [11]. For although the methods and concepts of practitioners vary, all true Taoist healers provide a framework for engaging with each patient in a dance towards wellness utilising the healer’s knowledge of the process and their awareness of their own significance within that process. This identification of imbalances and re-establishment of balance both physically and emotionally is one of the prime focuses of Taoist healing practice.

Theatrical nature of entering empty space

As any Trekkie knows, Space… is the final frontier. As Pendzik has suggested it as that place where the invisible becomes visible [12]. It forms a barrier which must be crossed and as Brook observed, the simple action, of crossing an empty space with others watching, is all that is necessary to begin the transformation of any space into a theatre stage [13]. It is also a liminal space - a transition space, one you must cross over. Where you leave something behind, yet you are not yet somewhere or something else [14]. When actors cross a space and engage the viewer in their dramatic acts, both the space and the viewers are transformed. The change from potential to actual performance enacts a change not only on the viewer from passive spectator to audience member but also on the space, from geographic location to a theatre stage [15].

Human presence is all that is necessary for any room, any space to be transformed into a theatre-no special attributes are needed. While Way advised drama educators that the drama room must be a space where anything can happen [16], in therapeutic work one must take this notion a little further. It is not only that it is a space where anything can happen, but it also must be a safe space where the possibility exists to revisit traumatic events, memories, and emotions and to transform them through the power of drama. One of the reasons why the space must be safe, is because within its boundaries participants transform into someone or something else, which carries the potential for revelation and/or significant personal meaning for all present in that space. While a dramatic moment which carries the seeds of a real personal transformation may happen in any theatrical performance, it is central to dramatherapy praxis.

Consequently, within a therapeutic context it is crucial that the parameters of the space are delineated.

This sense of a safe space where anything can happen must start with and be reinforced by the leader of the session. This means both literally and metaphorically defining the emotional and physical limits to the space. This step is essential so that each individual participating feels comfortable enough to engage various aspects of self in the environment in which they are working.

The influence of bodies, objects on energy in a (ny) space

Even a completely empty space is charged with possibility. It is full of energy. However, whatever/whoever inhabits the space affects the energy in the space, changes its flow and its architectureits Feng Shui. When anyone walks across any space, the audience sees moving architecture. It is not simply that they transform this empty space into a place of theatre, but they inhabit that space and in doing so also reshape the energy of the space itself. More than this, they interact with it and each item in the room has a relationship with the person walking through it.

Anyone moving across a space, carves it into both positive and negative space. Identifying for the audience things that are there and things that aren’t. The costume or clothes worn move. The colour evokes psychological responses. The flow of the fabric influences the way an individual cuts the space, which shapes it into something architecturally different. All of this affects what the audience sees and consequently how they react and how they feel about the individual inhabiting, moving across and carving sculpting the space. Then there’s the whole area of unexpected contradictions. So often the walk, like the voice, can be a jarring contradiction to what the viewer expected from an initial response to the individual’s stature and costume, based on expectations drawn from previous experience. Watching an individual cross, a space, or speaking, for the first time may alter perceptions of who this stranger is. As the old saying goes You never have a second chance to make a first impression.

Impoverished social performances

The interaction of human beings is the basic unit of all performance. The range of possible performances encompass the social, what we do in our everyday lives; and the theatrical, those make-believe performances where we act as if we are someone or something else. Irrespective of whether the performance takes place on a set of wooden boards, on a village green, in a shopping centre or any other location, theatrical magic must transform a space from simply being somewhere, to being somewhere special. For it is one of the wonders of the magic of theatre that by persuading the audience to suspend its disbelief, it is possible for any space to be transformed into the Fields of Ilyria, Castle Glamis or a country road. In theatrical productions, the performer’s skill is the key to the magic that creates this suspension of disbelief, but the mood of the scene is framed, and often enhanced, by the scenography: the skills of the Set, Lighting and Costume designers and the music used to create emotion in the viewer.

The appropriateness of any social performance is strongly influenced by the space in which it is presented. However, unlike actors in the theatre, all social actors perform on a stage that is, in part, of their own making. It is generally accepted that in each of these performances the individual takes on a role. For, whether knowingly or subconsciously, in any performance we select and present only part(s) of ourselves, an amalgam of various facets of who we are. The paradox is that the role we choose affects the stage upon which it is performed.

The choice of an appropriate role is crucial because the role is the mediator between who we are, and who others perceive us to be. Misreading the space or the scene or having unresolved or mixed emotions about the event, are likely to produce impoverished performances that identify the inadequacies of the performer and in so doing change the energy in the space. In the same way as the theatre actor rehearsing their idea of the definitive King Lear, while the cast is performing Hamlet - social actors who choose to perform as if they are making a professional presentation in a boardroom will NOT be appreciated by their partner who is looking for passion in the bedroom.

Once on the stage the invisible becomes visible; we show people who we are and just like Pirandello’s Six Characters we are constantly at the mercy of the demon of experiment [17]. For no matter how well, we may control our performances in our own heads, all social performance is one long unscripted improvisation. We are constantly at the mercy of the perceptions of others and how these perceptions reshape and redefine us for our audience - the other social actors with whom we share the space.

Bridging the space-making interpersonal connections

Space exists between things and people. As Samuel Beckett has suggested, we are born alone, astride of a grave and before we die, our lives are spent trying to connect with others. To do this we must take risks and ‘put our self out there’. We each must move, traverse the space, and bridge the gap between self and others. Much of the time our attempts to connect, to reach across the space leaves us fumbling in the dark. Stumbling along trying to understand and read the rules of social interactions. Trying to reach across the space between us and others. Slowly learning to ‘Act Normal’. This has all been exacerbated during the Covid-19 pandemic with directives to “Social Distance”, to create physical distance and to self-isolate, has amplified problems for persons living alone, especially seniors and persons with mental health problems

We grope and grasp at things and people and, if we are moderately successful, we learn to fit in. We find distractions, occupations and people that enable to feel that we are a fully integrated member of the community in which our lives are enacted. If we do not manage to grasp the rules of social interaction necessary to integrate within our community then we stand out as socially incompetent or ‘strange’ – we are an outsider. One only has to think how easy it is to know when someone is ‘a tourist’ in a new place. Even before speaking, they send off all sorts of nonverbal ‘signals’ that target them as ‘other’.

Double balance-learning to acting normal

We each need to learn how to fill the space between self and others appropriately. How to greet others, what to say, what to wear and so on. Taoists believe that we should seek to achieve balance between our inner world and the Universe, what they refer to as a Double Balance. This belief may also be applied to our day-to-day performances to help us understand that when we meet, we must seek to balance our reality with that of the others sharing our space. To do this, and not disturb the energy and connections within the space, each of us must learn to listen with all antennas up. We need to pay attention to all the verbal and non-verbal cues available to us and be fully in each moment - i.e., NOT be rehearsing the next moment or replaying previous one.

Seeing the space for what it is

What we see is affected by where we look and while familiarity often breeds contempt, it may also make individuals oblivious. Over the years I (BW) have taught in many locations around the world. One exercise I often use to start a morning session is “How I got here this morning”. This exercise asks each participant to briefly describe their journey from waking up in their bedroom to arriving at the classroom. What I found fascinating was not what people described but what they did not. The sights and sounds on my journey to work, the street vendors, the bird songs, the landscapes, were new to me. Time and time again I noticed things participants took for granted. This was especially true when I worked in Singapore, Shenzhen China, and the Gaza Strip. The participants were oblivious to the everyday sights and sounds of the location in which they lived. This reminded me of a time when I was also guilty of this. Early in my career, when I worked in Shrewsbury England, I encountered an Architect who was also an historian with a special interest in medieval buildings. He made me aware of carvings and sculptures on top of many of the buildings of which I had never been aware before; because I was always focused on making my way to work quickly and efficiently - and so, I never looked up.

Memory is a strange thing - revisiting traumatic space

Traumatic events do not occur in a vacuum, they occur in a space-a specific space that had objects and people in it. Trauma occurs because of an event that occurs in the space e.g., a child is abused (physically and/or emotionally) for something they do at the kitchen table. The traumatic event has physical elements attached to it. We remember some things very clearly and others, not so much-if at all. Moreover, our position during the events, just as with Brecht’s Street Scene, mean that several people experiencing the same event will remember it differently. The abused child, as an adult, may be able to remember the feel of cloth as they are reprimanded or their abuser’s smell or the speed at which the blow hit them. Recovering a memory is not always easy or simple. Every day, non-traumatic and unremarkable memories may be retrieved by taking something akin to a train journey. Remembering a single event image from the past acts as a ‘staging post’. From these memories of an event unfold, much like sitting in a rail carriage looking out at the scenery. However, we can only look out of one window at a time so our perspective, and memory of the event mirrors the blind men and the elephant.

However, traumatic events are often sealed away. They cannot be part of our everyday. To function, these emotionally charged, and sometimes violent images must be locked away and removed from view, otherwise these memories would likely affect our capacity to function normally in the mundane world of our day-to-day activities. Finding distance from the emotions attached to the trauma, so we do not relive the full effect of past events, is very important. The psychodrama exercise, I am a Lampshade, can provide some degree of therapeutic distance. In it the protagonist becomes a lamp shade, or similar inanimate object, that was present in the traumatic space when the trauma occurred. The protagonist now becomes a voyeur observing events rather than an individual experiencing them. In the hands of a skilful clinician the word “Freeze” may be used to halt the action. This coupled with providing time to reflect and discuss with the protagonist outside of the exercise, may help provide insights and sometimes even closure.

Dance-emotion in motion

As already mentioned, Dance-movement is an integral part of human performance it is also often referred to as emotion in motion. Recently I (GMF) was asked to help evaluate performances by young high school students enrolled in dance curriculum courses. The students had created and videoed their own performances. Due to covid-19, some of these took place in school settings, while others were done in home locales. To level the playing field, all dancers wore masks, and all were videoed by a single camera in a constant position. There was one performance that stood out for me: a solo performed in what appeared to be the dancer’s home that used the space and objects in fascinating ways.

The dramatic piece was a statement on the dancer’s reaction to the pandemic. It started with the young dancer, sitting at a very plain wooden table full of papers, with her head down on her hands and on the papers. She stood up and slowly walked/danced around to the front of the table. From her dance sequences and technique, it was clear she was a novice dancer, but she was emotionally riveting. She ended up under the table, legs crossed and drawn up to her chest, arms around her knees and her head resting on her crossed arms. Somehow, she managed to transform that position under the table to represent a prison cell, a cave, and a refuge. It was simple, but compellingly powerful. When she emerged, she transitioned into a very short series of simple pirouette-like turns and her arms went from an above-her-head dance position to a sudden break in form to shoulder height. As she turned, she bent over and instead of a pirouette, she swept all the papers off the table. The papers flew up and fanned out-an image of falling birds or thoughts or hope. It was a visual image of despair. She slowly returned to her seated position behind the desk, head down in her hands once more.

Therapy and performance in a Taoist context

In the above case, the dancer is the story: she has an intimate connection to and relationship with the space. Her interactions with the space help create a Taoist sense of balance for her. She communicates with her architectural surroundings and objects. The spotlight is on the performer, because she IS the resulting story, the audience cannot help but feel and experience it deeply, as they accompanied her on her emotional, physical, and spiritual journey.

This dance makes physical the Taoist idea of a dance toward wellness. The table is, at first glance, the prison. The girl is trapped AT it and BY the papers. But it could also be suggested that the table is her anchor in a sacred space. It enables her to negotiate her own balance and wellness through her interactions with it, as she transforms it into her ‘safe space’ by hiding under it. Through her movements, gestures, and stillness-in tableaux-like poses and snapshot momentary ‘stops’, she allows the table to become a cave or ‘security blanket’. There are fleeting times when we also see that the table, she’s hiding under for protection is also a prison cell, but it is through her energy that her transformation happens.

She isn’t altogether free from the table and the papers, but she emerges from under their yoke after sweeping the papers away. She still goes back to the table, and she’ll have to deal with those papers, but she somehow now seems more ‘in balance’ with things. She has rejected, retreated, rebelled, and found some sort of reconciliationand through her relationship with the table she is able to regain balance. Her relationship to the table is different at the end because she has, in her own way and time, come to terms with it-re-found her balance, her strength to continue and interact with the task as a ‘whole’ person rather than being fully dominated by, submissive to the table and those papers.

Creative moments-transforming inner space

As Schechner has suggested, transformation is the heart of theatre [18]. It is also the very heart of the therapeutic process. Stage actors must transform from who they are in real life to who they are on the theatre stage. Similarly, social actors must transform by forging a blend of intellectual emotional physical and spiritual energies into a single face, in theatrical terms, an appropriate mask which is then presented to others. To perform appropriately we each must create the ‘face’ we believe we need to present. To do this we must assess the needs of each scene and make choices about how to enter each space and engage with the other people and objects within it.

To be successful social actors we need to be able to read the scene on which we are being expected to perform. Our ability to read the space. As already mentioned, this is affected by many factors. And if all of this wasn’t enough, there is also the problem of ‘irrational fears’ NOT linked to a specific space or event e.g., general anxiety, claustrophobia. However, in the process of creating this new performance we become lost, if only momentarily, in a Creative Moment-a liminal state, itself a space between things, that possesses the potential to unite physical, intellectual, emotional, and spiritual aspects of our self. For in this momentary pause, when we are ‘lost to the world’, no matter how briefly, it is also possible that we may become open to change, and opportunities for healing to take place.

In a safe space where anything may happen, a skilled therapist using props, costume and lighting changes may effect changes in both the Feng Shui of the space and the responses in their clients. They may also encourage their clients to explore vocal tones, e.g., playing with pitch, pace and pause, or movement styles e.g., Laban’s 8 Effort Actions or Lecoq’s Verb Chains to change the way they inhabit the space [19]. A lot of work in dramatherapy, particularly with adults, is spent trying to help them achieve this.

Summary/Conclusion

In this article we applied a few Taoist principles (Feng Shui, Chi (energy), Dance Towards Wellness, and Double Balance), to explore Empty, Performance and Therapeutic Space. We presented some of the reciprocal ways that spaces, and particularly our world maps and points of view, affect our social performances. But space may not only restrict us it may also act as a catalyst for us to expand our horizons e.g., Cervantes who from the confines of his jail cell opened his mind to create spaces inhabited by Don Quixote.

In the double balance, when there is a unity of body mind and spirit, there is to be found a parallel between performance and therapy, healer and client, artist, and audience. We would suggest that there are many parallels between and among them that could be of benefit to all if made aware of them. Ultimately, it is always the ‘space and energy’ between healer/performer(s) and patients/ audience where transformation is invited and occurs.

References

- (1982) There are many excellent texts on Taoism. However, as an introduction I(BW) always required my students to read, Hoff, particularly, pp 1-7.

- Feng Shui, which literally translates as Wind-Water, is a traditional ancient Chines practice which considers the energies present in a space that help individuals be in balance within their surroundings. For more details see Field, S. L. "The Zangshu, or Book of Burial". Professor Field's Fengshui Gate. Archived from the original on 2020-05-21.

- Berger J (1972) Ways of Seeing. Penguin, London, UK.

- Korzybski A (1958) Science and Sanity. Lakefield Conn, International Society for General Semantics.

- Gordon D (1978) Therapeutic metaphors: Helping others through the looking glass. Meta Publications, Cupertino, Calif, USA.

- https://head.hesge.ch/arts-action/IMG/pdf/The_Street_Scene_A_Basic_Model_for_an_Epic_Theatre.pdf

- Robbie S, Warren B (2020) Dramatising the shock of the new: Using Arts-based embodied pedagogies to teach life skills. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 42(5).

- Kahane A, Barnum J (2017) Collaborating with the enemy: How to work with people you don't agree with or like or trust.

- Chi (also written as Qi, or Ch’i) has no direct translation in English. It is often translated simply as “energy” however, “vital force”, “life force” or even “creative force” more accurately describes it.

- Klate J (1980) The TAO of Acupuncture. Ann Arbor, MI, UMI, USA.

- Veith I (2002) Huang Ti Nei Ching Su Wên=The yellow emperor's classic of internal medicine. Berkeley, University of California Press, USA.

- Huang YC (1995) How to work with disabled students. TAI CHI p. 19: 3.

- Pendzik S (1988) Dramatherapy as a form of modem shamanism. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology 20(1): 81-91.

- Brook P (1968) The empty space, Penguin, London, UK.

- Seale A (2016) The liminal space-Embracing the mystery and power of transition from what has been to what will be.

- Way B (1967) Development through drama London, Longmans, UK.

- Bentley E (1952) Naked masks: Five plays by Luigi Pirandello. E.P. Dutton, and Co, New York, USA.

- Schechner R (1985) Between theatre and anthropology. Routledge, New York, USA.

- Warren B, McQueen Fuentes G (2019) Joining up the dots: Using Laban and Lecoq to help develop dramatic impulses and Negotiate Space, Incite/Insight.

© 2022 Bernie Warren, This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)