- Submissions

Full Text

Psychology and Psychotherapy: Research Studys

The Relationship between Ethnic Identity and Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Symptoms in University Students in Iran

Fereydouni S1,2, Fereidouny Doshmanzeiary S3 and Forstmeier S1*

1Developmental Psychology and Clinical Psychology of the Lifespan, Institute of Psychology, Germany

2Department of Educational Psychology, Iran

3Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Iran

*Corresponding author: Forstmeier S, Developmental Psychology and Clinical Psychology of the Lifespan, Institute of Psychology, Germany

Submission: May 06, 2021Published: June 01, 2021

ISSN 2639-0612Volume5 Issue1

Abstract

Ethnic identity, as a component of one’s individual identity, refers to the commitment to a cultural group and engagement in its practices. A healthy ethnic identity development should contribute to wellbeing. The aim of the present study is to investigate the strength of association between ethnic identity and depression, anxiety, and stress in Iranian university students. A total of 184 students from three Iranian universities filled in the Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM) and the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-42). Ethnic identity correlates significantly and negatively with depression, anxiety, and stress. The sense of belonging to the ethnic groups shows the strongest and most significant correlations with depression, anxiety, and stress. This result is compared to the findings of studies with other ethnic groups. It seems that the strength of correlation between ethnic identity and mental problems is higher in Iranians than in European Americans or Europeans, which might be due to the differing role of ethnic identity for mental health in different ethnic groups.

Keywords: Ethnic identity; Culture; Depression; Anxiety; Stress; Students

Introduction

Ethnic identity can be conceptualized as a component of one’s individual identity and

refers to “commitment to a cultural group and engagement in its cultural practices (e.g.,

culture, religion), irrespective of racial ascriptions” [1]. The development of ethnic identity is

embedded in one’s individual identity development, but at the same time influenced by the

socialization processes within the ethnic group that the individual belongs to. Current models

of ethnic identity, such as Phinney’s [2] three-stage model of ethnic identity development, are

grounded in the work of Erikson [3] and Marcia [4]. Erikson [3] describes the development

of one’s identity as a lifelong process, beginning in childhood, with a peak in adolescence

and early adulthood, but continuing until late adulthood. Marcia [4] described processes of

identity development, namely exploration of identity issues and commitment to significant

and related identity domains.

Building on these more general identity development models, Phinney [5] describes three

stages of ethnic identity development. First, commitment and attachment, i.e., the extent of

an individual’s sense of belonging to his or her group; second, exploration, i.e., engaging in

activities that increase knowledge and experiences of one’s ethnicity; and third, achieved

ethnic identity, i.e., having a clear sense of group membership and what one’s ethnicity means

to the individual. Related to these stages, Phinney [5] describes three dimensions of ethnic

identity that are common across ethnic groups, namely affirmation and belonging, ethnic

identity achievement, and ethnic behaviors. Following this multidimensional model, he

developed the Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM) which is one of the most often

used measures of ethnic identity [1,6].

Ethnic identity and mental health

The above-mentioned models of general identity development posit that a healthy identity

development leads to a positive and well-adjusted self-concept and self-acceptance. Likewise,

a healthy ethnic identity development, which can be described by a high sense of belonging to the ethnic group, a high ethnic identity achievement, and adequate

ethnic behaviors, should contribute to wellbeing. This has been

supported by several studies in various ethnic groups.

Positive wellbeing: A strong sense of ethnic identity correlates

positively with positive wellbeing scales, e.g., self-esteem,

eudaemonic wellbeing, and satisfaction with life, in North-

American multicultural samples [7-9], in North-American people

of color [10], in Asian Americans [11-13], in Mexican adolescents

[14], in Mexican American women [15] in a Greek sample [16], and

in white Americans [17].

Depression: Since psychopathological syndromes such as

depression and anxiety are inversely associated with wellbeing,

ethnic identity correlates negatively with depression in North-

American multicultural samples [8,18], in North-American people

of color [10], in Latino Americans [19], and in African Americans

[20-22].

Anxiety: As with depression, ethnic identity correlates negatively with anxiety symptoms in African Americans [22]. A systematic review on this topic concluded that there is relatively much research with samples of African and Latino Americans, but a dearth of research with Asians and Asian Americans [23]. We want to add that there is almost no research on the association of ethnic identity and mental health in Muslim countries such as Iran. To the best of our knowledge, there is only one published article on this association, however, it is only published in the Farsi language. Alijani [24] found that a positive religious identity is associated with lower symptoms of depression and anxiety. Therefore, the association of ethnic identity and mental health in Iran should receive more attention.

Aim of the present study

The aim of the present study is to investigate the strength of association between ethnic identity and depression, anxiety, and stress in Iranian university students.

Methods

Participants

Inclusion and exclusion criteria: The participants of this study consisted of university students in the South-West of Iran. They were recruited from the Islamic Azad Universities of Gachsaran, Noorabad, Mamasani, University of Educational Sciences, and the Art University of Shiraz. Overall, the sample included 184 participants with a mean age of 21.89 years (SD 0.29). They were included in the study after they had given their consent to participate. Some of the participants lived in urban surroundings, some in a rural area. All of them were Persians and Muslims.

Informed consent

The objectives and goals and detailed information about the assessment were explained to the participants. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to inclusion. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Islamic Azad University of Gachsaran, Iran.

Measures

Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM)

The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM) was designed by Phinney [5]. The aim of the questionnaire was to measure three components of ethnic identity that are common across ethnic groups, namely affirmation and belonging (five items), ethnic identity achievement (seven items), and ethnic behaviors (two items). It consists of 14 questions with a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 4. Some items are reversely coded. A sample item for affirmation and belonging is “I have a strong sense of belonging to my own ethnic group”; for ethnic identity achievement “I have a clear sense of my ethnic background and what it means for me”; for ethnic behaviors “I participate in cultural practices of my own group, such as special food, music, or customs”. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.80 for the total scale, 0.83 for affirmation/belonging, and 0.57 for ethnic identity achievement in the present sample. Validity has been shown, e.g., by a moderate and positive correlation with self-esteem [5].

Depression, anxiety and stress scale (DASS-42)

The DASS-42 is a 42-item self-report inventory that assesses symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress in the previous seven days [25]. The depression subscale includes items evaluating symptoms such as anhedonia, feelings of sadness, worthlessness, hopelessness, and lack of energy. The anxiety subscale includes items evaluating physiological arousal, phobias, and situational anxiety. The stress subscale includes items evaluating symptoms such as difficulty in achieving relaxation, state of nervous tension, agitation, overreaction to situations, irritability, and restlessness. Each item is rated from 0 to 3 according to severity or frequency of the symptom. Each subscale has 14 items, and a participant’s score in each subscale is obtained by the sum of all items related to a subscale. The DASS-42 has been shown to have good psychometric properties in psychiatric and non-psychiatric populations in various countries, and the three-factor structure has also been approved. We used the Persian (Farsi) translation of the DASS-42 [26]. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.94 for depression, 0.8 for anxiety and 0.91 for stress in the present sample.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software, version 26 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois). The descriptive statistics section describes the data in terms of mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum. Pearson correlations between the variables were calculated to assess their associations.

Result

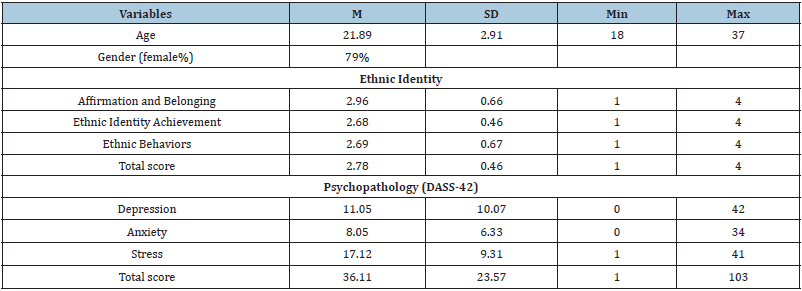

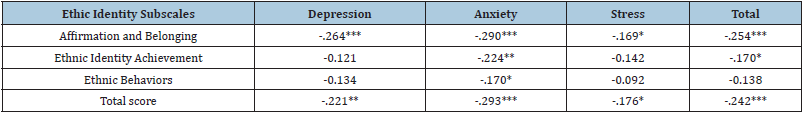

Mean ethnic identity total score is M = 2.78 (SD = .46), which is, on a Likert scale from 1 to 4, a moderately high value. Mean values for the ethnic identity subscales as well as those for depression, anxiety, and stress are presented in Table 1. The correlations of ethnic identity with depression, anxiety, and stress are presented in Table 2. Ethnic identity total score correlates negatively with all psychopathological variables with a moderate effect size. The correlation is significant for depression (r = -.22; p < .01), anxiety (r = -.29; p < .001), stress (r = -.18; p < .05), and DASS-42 total score (r = -.24; p < .001). Regarding the ethnic identity subscales, affirmation/belonging shows the strongest and most significant correlations with depression, anxiety, and stress. The other two subscales, i.e., ethnic identity achievement and ethnic behaviors, correlated significantly only with anxiety, but not with depression and stress (Table 2).

Table 1: Characteristics of the sample (N = 184).

Table 2: Correlations of ethnic identity with depression, anxiety, and stress (N = 184)

Notes: *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Discussion

In a sample of university students in Iran, we found negative correlations of ethnic identity with depression, anxiety, and stress that were statistically significant or even highly significant. The affirmation/belonging subscale shows the strongest and most significant correlations with depression, anxiety, and stress.

Comparison with other studies on the association of ethnic identity with mental health

The MEIM score of M = 2.78 (SD = .46) is similar to that obtained in the study by Taghizadeh [27] with M= 2.98 (SD = .61) in male students and M = 2.82 (SD = .59) in female students in Iran. The DASS is usually used in its 21-item version in Iran, therefore we compare our results of the DASS-42 with a Turkish sample of university students. The scores in our sample were similar to those in the study of Demirbatir [28]: for depression M = 11.05 (10.07) vs. 12.24 (SD = 9.52), for anxiety M = 8.05 (6.33) vs. 11.67 (SD = 8.74), and for stress M = 17.12 (9.31) vs. 16.86 (SD = 9.38). The correlation between ethnic identity (MEIM total score) and psychopathological variables found in the present study were moderate, between r=-.22 for depression and r = -.29 for anxiety. With regard to depression, Williams et al. [22] found a correlation between MEIM total score and depression of r = -.27 (p< .01) in African Americans and r = .04 (p not significant) in European Americans, and Roberts et al. (8) of r = -.09 (p not significant) in a North-American multicultural sample. With regard to anxiety, Williams et al. [22] found a correlation between MEIM total score and anxiety of r = -.35 (p < .01) in African Americans and r = -.09 (p not significant) in European Americans. This comparison shows that the strength of association between ethnic identity and mental health problems differs between ethnic groups. This might be explained by the differing role of ethnic identity for mental health in different ethnic groups. Ethnic identity might not be as important in European Americans and Europeans, and, thus, mental health might depend more on other variables such as satisfaction with personal goals (in contrast to goals of the ethnic group). On the contrary, ethnic identity might be of higher importance for Iranians or African Americans and, thus, contributes more strongly to mental health. As Williams et al. [22] put it, “our findings support assertions that ethnic identity is less salient to European Americans” [29].

Limitations

There are some limitations to this study that should be considered in the interpretation of the results. First, this is a cross-sectional study, thus, no causal inferences on the association between ethnic identity and mental health can be made. Second, we used no other variables possibly influencing mental health or moderating this association. Further variables would be very interesting to explain this association and its mechanisms. Future studies should address the role that other variables may have in this association in a longitudinal study. Third, only the presence of depression, anxiety, and stress was investigated. Measures of positive wellbeing as well as psychiatric diagnoses have not been applied. Finally, the sample consists of university students, but not other young adults with a different working career, and no other age groups in Iran. Therefore, we cannot generalize our results to other Iranian or Muslim populations.

Practical consequences for treatment

Based on our finding that ethnic identity is negatively

associated with depression, anxiety, and stress, the treatment

of these psychopathological syndromes should take ethnic and

cultural themes into account. It has been suggested that tailoring

the treatment to the patient’s values improves its efficacy [30].

Furthermore, in a Muslim country like Iran, ethnic and religious

values might be associated. It is known that religious patients

usually want to discuss spiritual issues in psychotherapy [31].

Therefore, psychotherapists should be sensitive to the patient’s

preferences regarding ethnic (e.g., discrimination experiences) and

spiritual issues and also to the inclusion of interventions that may

be in conflict with the patient’s beliefs.

A study in the Netherlands studied asylum seekers’ needs

and expectations concerning psychotherapy in order to develop a

culturally sensitive psychosocial intervention [32]. The participants

in this study originated from Iran and other Middle Eastern

countries. They understood their mental health problems mainly

in association with post-migration stressors and not with past

traumatic experiences. In addition, they hesitated to talk about their

problems because of shame and the fear of negative stigma. The

question arises as to how important the patient’s concealment of

aspects of their cultural identity is for the success of psychotherapy.

In a multicultural American student sample, Drinane et al. [33]

found that withholding cultural information while engaging with

the therapist in a session correlates negatively and moderately (r

= -.44) with the patient’s improvement in therapy. Thus, concealing

and incorporating aspects of ethnic and cultural identity is

important for the efficacy of mental health treatments.

References

- Helms JE (2007) Some better practices for measuring racial and ethnic identity constructs. Journal of Counseling Psychology 54(3): 235-246.

- Phinney JS (1993) A three-stage model of ethnic identity development in adolescence. In: Bernal ME, Knight GP, Herausgeber (Eds.), Ethnic identity: Formation and transmission among Hispanics and other minorities. University of New York Press, Albany, USA, pp. 61-79.

- Erikson EH (1994) Identity and the life cycle. Norton, New York, USA.

- Marcia J (1980) Identity in adolescence. In: Adelson JH (1980) Handbook of adolescent psychology. Wiley, New York, USA, pp. 159-187.

- Phinney JS (1992) The multigroup ethnic identity measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research 7(2): 156-176.

- Phinney JS, Ong AD (2007) Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current status and future directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology 54(3): 271-281.

- Kiang L, Yip T, Backen GM, Witkow M, Fuligni AJ (2006) Ethnic identity and the daily psychological well-being of adolescents from Mexican and Chinese backgrounds. Child Dev 77(5): 1338-1350.

- Roberts RE, Phinney JS, Masse LC, Chen YR, Roberts CR, et al. (1999) The structure of ethnic identity of young adolescents from diverse ethnocultural groups. The Journal of Early Adolescence 19(3): 301-322.

- Syed M, Walker LHM, Lee RM, Taylor AJ, Zamboanga Bl, et al. (2013) A two-factor model of ethnic identity exploration: Implications for identity coherence and well-being. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 19(2): 143-154.

- Smith TB, Silva L (2011) Ethnic identity and personal well-being of people of color: A meta-analysis. J Couns Psychol 58(1): 42-60.

- Iwamoto DK, Liu WM (2010) The impact of racial identity, ethnic identity, Asian values, and race-related stress on Asian Americans and Asian international college students’ psychological well-being. J Couns Psychol 57(1): 79-91.

- Yip T, Fuligni AJ (2002) Daily variation in ethnic identity, ethnic behaviors, and psychological well-being among american adolescents of Chinese descent. Child Dev 73(5): 1557-1572.

- Yoo HC, Lee RM (2005) Ethnic identity and approach-type coping as moderators of the racial discrimination/well-being relation in Asian Americans. Journal of Counseling Psychology 52(4): 497-506.

- Taylor UAJ (2004) Ethnic identity and self-esteem: Examining the role of social context. J Adolesc 27(2): 139-146.

- Diaz T, Bui NH (2017) Subjective well-being in Mexican and Mexican American women: The role of acculturation, ethnic identity, gender roles, and perceived social support. J Happiness Stud 18(2): 607-624.

- Vleioras G, Bosma HA (2005) Are identity styles important for psychological well-being? J Adolesc 28(3): 397-409.

- Waterman AS (2007) Doing well: The relationship of identity status to three conceptions of well-being. Identity 7(4): 289-307.

- Brittian AS, Kim SY, Armenta BE, Lee RM, Taylor AJ, et al. (2015) Do dimensions of ethnic identity mediate the association between perceived ethnic group discrimination and depressive symptoms? Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 21(1): 41-53.

- Taylor UAJ, Updegraff KA (2007) Latino adolescents’ mental health: Exploring the interrelations among discrimination, ethnic identity, cultural orientation, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms. J Adolesc 30(4): 549-567.

- Mandara J, Harden GNK, Richards MH, Ragsdale BL (2009) The effects of changes in racial identity and self-esteem on changes in African American adolescents’ mental health. Child Development 80(6): 1660-1675.

- Street J, Britt HA, Barnes WC (2009) Examining relationships between ethnic identity, family environment, and psychological outcomes for african american adolescents. J Child Fam Stud 8(4): 412-420.

- Williams MT, Chapman LK, Wong J, Turkheimer E (2012) The role of ethnic identity in symptoms of anxiety and depression in African Americans. Psychiatry Research 199(1): 31-36.

- Drake RD, Seaton EK, Markstrom C, Quintana S, Syed M, et al. (2014) Ethnic and racial identity in adolescence: Implications for psychosocial, academic, and health outcomes. Child Development 85(1): 40-57.

- Alijani M (2006) The relationship between religious identity and mental health in students of Islamic Azad University. Psychological Studies 2: 89-106.

- Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF (1995) Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales. Aufl Sydney: Psychology Foundation.

- Afzali A, Delavar A, Borjali A, Mirzamani M (2007) Psychometric properties of DASS-42 as assessed in a sampel of kermanshah high school students. Journal of Research in Behavioural Sciences 5: 81-92.

- Mohammad TA, Khoshkonesh A, Zademohamadi AZ, Habibi M (2014) Comparison of ethnic identity and subjective well-being in Iranian ethnicities 14(52): 135-158.

- Demirbatir RE (2012) Undergraduate music student’s depression, anxiety and stress levels: A study from Turkey. Procedia-social and behavioral sciences 46: 2995-2999.

- McDermott M, Samson Frank L (2005) White racial and ethnic identity in the United States. Annual Review of Sociology 31(1): 245-261.

- Sotsky SM, Glass DR, Shea MT, Pilkonis PA, Collins JF, et al. (1991) Patient predictors of response to psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy: Findings in the NIMH treatment of depression collaborative research program. Am J Psychiatry 148(8): 997-1008.

- Rose EM, Westefeld JS, Ansley TN (2008) Spiritual issues in counseling: Clients’ beliefs and preferences. Journal of Counseling Psychology 48: 61-71.

- Slobodin O, Ghane S, De Jong, Joop TVM (2018) Developing a culturally sensitive mental health intervention for asylum seekers in the Netherlands: A pilot study. Intervention 16(2): 86-94.

- Drinane JM, Owen J, Tao KW (2018) Cultural concealment and therapy outcomes. Journal of Counseling Psychology 65(2): 239-246.

© 2021 Forstmeier S, This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)