- Submissions

Full Text

Psychology and Psychotherapy: Research Studys

A Clinical Experience Informed Variation to the CBT Explanation and Treatment of Worry

Chigwedere C* and Wilson CE

Trinity College Dublin, Ireland

*Corresponding author: Chigwedere C, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland

Submission: May 04, 2021Published: May 25, 2021

ISSN 2639-0612Volume5 Issue1

Abstract

The Intolerance of Uncertainty (IOU) model of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) [1] integrates a range of psychological processes including positive beliefs about worry and a negative problem orientation, with IOU as a central vulnerability and maintaining factor. We describe the rationale behind a treatment approach applied as an adjunctive intervention in a non-inferiority trial comparing Cognitive Behavioural Psychotherapy (CBT) and Emotional-Focused Therapy (EFT); [2]. The approach incorporated amendments to the Dugas et al. [3] protocol, including targeting developmental factors and triggering events. Here we describe the clinical observation informed rationale for the amendments and how they were incorporated.

Keywords: Cognitive behavioural therapy; Generalised anxiety disorder; Intolerance of uncertainty; Worry; Schema; Attachment; Treatment; APA: American Psychiatric Association

Abbreviations: IOU: Intolerance of Uncertainty; GAD: Generalized Anxiety Disorder; CBT: Cognitive Behavioural Psychotherapy; EFT: Emotional-Focused Therapy

Learning Outcomes

a. Describe the rational and hypotheses for amendments introduced in a study

b. Consider an alternative explanation of intolerance of uncertainty

c. Help to expand explanation and treatment options in the treatment of worry

Introduction

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) is associated with distressing and uncontrollable worry [3]; American Psychiatric Association {APA}, [4], with symptoms including restlessness, fatigue, irritability, tension and sleep disturbance [5]; World Health Organisation {WHO}, [6,7], which cause personal and interpersonal distress and functional impairment (APA, 2000). GAD is highly co-morbid with other disorders [8] and challenging to treat [9], with only 50% of those entering treatment achieving outcomes within non-clinical ranges at discharge [10,11]. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) has proven efficacy in the treatment of GAD. Its leading models include worry avoidance [12,13], metacognition [14,15], emotion regulation [16], and Intolerance Of Uncertainty (IoU). Based on clinical observation and theory, we added to Dugas & Robichaud’s [3] model to include a greater focus on developmental experiences, environmental triggers and perception of worry as premonitions. This adapted approach was included as an adjunctive approach in a non-inferiority trail comparing CBT and Emotion Focused Therapy (EFT). Though the model proposed by Dugas and colleagues is comprehensively described and researched, the thinking behind our amendments is not. For this reason, we will outline a three-phase maintenance explanation, with a five-module treatment structure. We will briefly outline the IoU model, followed by three concepts we think are important to our hypothesis, then an adapted worry maintenance cycle and related treatment approach.

The IoU model

The IoU model proposes that worry, a core symptom of GAD, may result directly from an

exceptional sensitivity to uncertainty. IoU is defined as “a trait of the individual, characterized by a predisposition to react negatively to an uncertain event or

situation, independent of its probability of occurrence and its

associated consequences” [17]. Due to the ubiquitous nature of

uncertainty, worry becomes diffuse, occurring in response to any

uncertain situation. For the interested reader, Dugas and Robichaud

[3] offer an extensive review of important IoU research, describing

a multifaceted explanatory and treatment approach.

They describe four main maintenance factors:

1) Intolerance of uncertainty,

2) Positive beliefs about worry,

3) Negative problem orientation and

4) Cognitive avoidance.

Treatment is offered within six modules of

1) Psychoeducation,

2) Uncertainty recognition and behavioural exposure to

real-life situations,

3) Re-evaluation of beliefs about worry as useful,

4) Problem solving,

5) Imaginal exposure to hypothetical worries and

6) Relapse prevention.

We hypothesize that developmental experiences, situational

worry, triggers, and a novel concept we have termed premonition

bias are also important.

Developmental experiences

Individuals who worry report more frequent traumas and childhood adversity, including difficult attachments, than non-anxious people [18,19]. Attachment experiences, such as enmeshment and role reversal with childhood primary caregivers [20], may be developmental precursors to interpersonal difficulties associated with worrying. They may lead to problematic internal working models of relationships (schemas) [21-24]. Young et al. [25], describe an 18-schema, 5-domain structure, which may be associated with worry [26-28]. IoU may be a function of schemas, a looming cognitive style [29] or hypervigilance for negative outcomes due to the priming effect of past negative experiences [30- 33]. It may mediate the relationship between anxious attachment and adult worry [34-37]. Furthermore, targeting attachmentrelated factors in treatment may enhance standard CBT for GAD and schema therapy has some efficacy in treating GAD. We propose that the IoU model may benefit from the inclusion of some schemafocused principles as described by Young et al. [25]. Such schemas may play an important role in the triggering of worry.

Triggering of Worry

Through associative learning, attachment-related experiences (e.g. abuse) may become Unconditioned Stimuli (UCS), paired with innocuous events (including physiological and affective states) in the learning environment [38]. Fear may be an Unconditioned Response (UCR) in this Stimulus-Stimulus (S–S) paring. However, innocuous elements before and during the event acquire the UCS’s fear-inducing qualities in a stimulus–response (S–R) association. For example, Joe’s (a composite patient) father frequently went drinking, leaving his young son alone and terrified for many hours. Later, as an adult, normal life events (e.g. his wife or children walking away from him after a disagreement) became conditioned stimuli (CS) which activated intense fear, anxiety and worry (i.e., Conditioned Response {CR}) for Joe. As such, schemas such as abandonment may represent the activation of implicit memories in current contexts. Schema activation and resultant worry, may represent a lowered threshold for perceiving implicit memory traces, which are then involuntarily retrieved by anything that resembles the CS. They represent a strong perceptual priming for the CS, triggered by anything that might vaguely resemble previously encountered negative experiences.

Such activation may strengthen the schema by creating new pairings between the CS and innocuous elements in the new environment, which elaborate and reconsolidate it. As such, the activation of worry may create more worry triggers. Schemas represent broad overgeneral implications [39]. Associated memories may be overgeneral and implicit, easily activated by traces of contextual elements that are not well discriminated from others, resulting overgeneral predictions of future events and worry behaviours. In a small study (Chigwedere, in preparation) worriers demonstrated overgeneral memory in the retrieval of past memories and future predictions. Worrying may have been an adaptive coping response for a child (like Joe above), who lacked resources for resolving the issues confronting him. However, verbal worry reduces autonomic arousal, which reinforces further worry behaviours [40-42].

Premonition bias

We propose that besides reducing arousal and avoiding distressing images, worry may have an unintended function that we have called ‘premonition bias’. Though support for this concept is currently lacking, our clinical experience is that worries are often described as having a quality of reality, as though they will eventually come true, making them believable. This might explain their fearfulness and appraisal as preparative, predictive and avoidant of negative outcomes. Worry may represent efforts to respond to negative appraisals of, and fearful predictions from current events [43]. Such appraisals and predictions are arrived at on the basis of retrieved memories of previously encountered events [44], hence the quality of reality and sense of urgency to resolve them. For example, Joe’s fear of abandonment was based on past experience and a lowered threshold for perceiving it in ambiguous situations. He was primed to perceive abandonment when his wife and children walked away, which required solutions (i.e. worrying).

Importance of the current conceptualisation

The distinction between the above explanation and the

conceptualisation of Dugas and colleagues is subtle but important.

Where they propose that what is avoided is the arousal, distress associated with fearful images of the future, we propose that it is the

triggering event in the current environment. It is avoided because

it contains reminders of memory traces of the events that gave rise

to the schema, and so activates the CR of fear, leading to worry as

solution finding. This conceptualisation potentially changes the

focus of treatment from future-focused worry to tolerance of the

ambiguous trigger in the current environment.

We propose that ambiguous events result in a worry

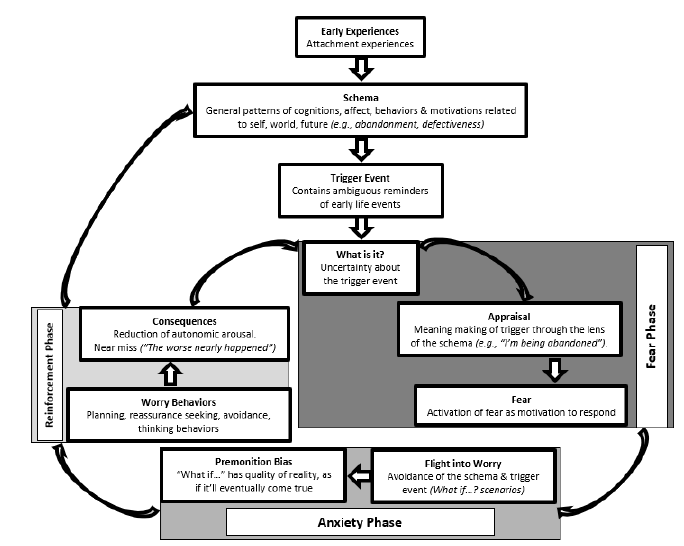

maintenance cycle in three phases

(1) A sense of imminent threat or fear,

(2) Apprehensive anxiety about remote, unpredictable

hypothesized outcomes, and

(3) Reinforcement, each requiring different interventions.

Though we describe them in the worry cycle below as three

distinct phases, in reality, they can be simultaneous or overlapping

and mutually activating.

The worry cycle

Fear Phase: This is a brief, three-stage, high-arousal state in

response perceived imminent threat, involving (1) orienting threat

perception, (2) appraisal of the perceived threat and (3) fright

stages.

What is it? The initial response to the trigger is a “Shto eta?”

or “What is it?” response [45]. This is a reflex, freezing response,

which we consider to be the current threat or “in the moment”

uncertainty. It is an orienting response facilitating a stop-looklisten

threat perception [46-48]. Imagine walking through a forest

associated with bear sightings. You are likely to be hypervigilant for

bears. An ambiguous rustle will make you freeze, attend and wonder

“What is it?” In the case of worry, one may be hypervigilant for the

schema. Like the rustling, ambiguous events activate the freeze and

attend response, during which sensory and attentional resources

are directed towards evaluation of the source of the threat stimulus.

Appraisal/meaning making: We propose that “What is it?” is

immediately followed by a rapid appraisal stage. For example, “What

is it?” is rapidly followed by an awareness of “I don’t know what it is,”

(i.e. uncertainty) then “What if it’s a threat/bear!” (i.e. explanatory

appraisals retrieved from stored information as appraisal of the

rustling). This involves the retrieval of autobiographical memories,

encoded in terms of their general sense as implicational, schematic

aspects [49]. Such schemas give an overgeneral meaning or

appraisal to the current context (i.e. rustle = bear). The earlier

case of Joe offers an example of this process (i.e. walking away =

abandonment).

Such appraisals and memories are involuntarily, directly and

rapidly retrieved by ambiguous cues or memory reminders within

environments, not through voluntary, indirect and effortful recall

[50-52]. They will be accompanied by sensory and emotional

memory fragments, similar to trauma memories [53], but in worry,

processing may stop at the overgeneral, rather than the event

specific knowledge level [54-56]. Such overgeneral memories will

be accompanied by high arousal and emotionality. “Fear Phase”. The

rapid negative appraisal of ambiguity results in a sense of imminent

threat (e.g. “I’m…being abandoned/…under threat”), because ‘it

is better to be safe than sorry’. Arousal is increased, uncertainty

is experienced as frightening and intolerable, which motivates

prediction of outcome scenarios. At this stage, one reaches the peak

of a brief “Fear Phase”. which started with a sense of not knowing

(i.e. what is it?) and is associated with intense amygdala activation

[57].

Anxiety “Fear Phase” before: This is a prolonged prolonged,

apprehensive state of lower intensity arousal than the fear phase,

comprising (1) flight into worry and (2) premonition bias stages.

Flight into worry: Fear motivates safety-seeking and activates

a flight phase. However, ambiguous triggers, overgeneral appraisals

and high uncertainty preclude the identification of behavioural

safety-measures. Overgeneral memories and their appraisals are

accessed to facilitate solution-finding and plan goals, which will

be abstract and verbal and reduce autonomic arousal [58]. This

leads to cyclical, verbal worry in a quest for certainty. Indeed, such

overgeneral encoding and retrieval have been associated with both

poor problem-solving [59-61] and overgeneral imaginings of the

future, which may not be uncommon in worry (Chigwedere, in

preparation).

Premonition bias: Worry may be a freeze-fright-flight-fight

response to avoid the trigger event. Uncertainty may be experienced

differently at each stage, though its main driver may be schema

activation in the current environment. The worry phase may

represent flight and fight responses. One flees “into worry” avoid

the trigger and searches for solutions as fighting. Unfortunately,

the identified hypothetical solutions are perceived as highly

likely to occur at an unknown future point (i.e. premonition bias),

representing non-specific and unpredictable threats. Consequently,

the individual experiences anxiety, an anticipatory response to

uncertain, unpredictable threat, associated with activation of the

bed nucleus of the stria terminalis [62-64]. Premonition bias may

partially account for positive worry beliefs. As such, positive beliefs

about worry may initially be responses to simply experiencing

worry [65], which strengthen in believability to become part of the

maintenance cycle of worry.

Reinforcement Phase

Worry behaviours: Worry predictions and premonition

bias increase uncertainty and activate overt and covert worry

behaviours. Covert responses may include mental actions such

as distraction, thinking positively, thinking of likely scenarios and

solution finding. Overt worry behaviours may include reassurance

seeking, behavioural avoidance and checking.

Reinforcement: Worry behaviours result in reduced arousal

and a perception of ‘near miss’ (i.e. “If I had not done safetybehaviours,

a negative outcome really would have come true”).

Consequently, the worry behaviours are reinforced, and the near

miss strengthens the belief in the schema. Figure 1 diagrammatically

represents this hypothesised worry cycle.

Figure 1: Three-phase model of worry maintenance.

The treatment

As already stated, we will mostly focus on describing the adjunctive, novel components of the treatment. The Dugas & Robichaud [3] approach was followed in the Timulak et al. [2] study. However, unlike Dugas and Robichaud, in that study we introduced imaginal exposure to worry earlier in the treatment, as reported by others [66]. It is worth noting that the approach described here was successfully applied as a standalone treatment in a small case series (Chigwedere & Moran, under review). The approach was designed to be used flexibly in a modular system.

Module 1: Socialisation to the model, goal setting and self-monitoring: This module follows a thorough assessment. The main objective is socialising the patient to the model and psychoeducation about IoU. The therapist offers the explanatory rationale for the maintenance of worry, the concept of uncertainty and the synergy of cognitions, affect and behaviours. The dimensionality of worry is reinforced using metaphors, such as the allergy metaphor. Principles of imaginal exposure are introduced. In-session practice is used to demonstrate the cognitive avoidance function of worry, demonstrating how it avoids ambiguous, in-themoment triggers leading to increased uncertainty and worry. Most patients find a description of worry using simple explanations of neural structures helpful, particularly the idea that worry may reduce neural connectivity and the integrity of mechanisms such as the amygdala and uncinate fasciculus, which may be reversible with mindfulness and CBT [67]. Hypothetical worrying is described as an apprehensive anxiety response, with a simple description of prefrontal cortex-limbic system connectivity. It is described to patients in simple terms as a cognitive activity, whose function is akin to a covert safety-behaviour. The concept of premonition bias is demonstrated by simply asking the patient to describe the quality of their worrying thoughts, whether they feel like “just your own fears or realities that could actually come true.”

Depending on therapist skill, as early as the socialisation exercise at the end of the assessment, the difference between hypothetical worry and focusing on the real problem (i.e. the trigger and the uncertainty) is demonstrated. Some patients have been able to begin to practice ‘sitting with’ internally or externally activated sensory images of the trigger and associated uncertainty. Self-monitoring is practiced in tandem with practicing identifying and tolerating uncertainty and its triggers. At the start of the first session following assessment, therapist and patient collaboratively identify specific end-of-treatment goals and each session ends with a specific homework task. Depending on therapist skill and patient resources, this module could be up to 3 sessions. Worry monitoring uses a novel Worry/Uncertainty Monitoring Diary, which distinguishes current uncertainty triggers from their hypothetical worry consequences.

Module 2: Self-monitoring and worry recognition training: While socialization, self-monitoring and tolerance training can start as early as the end of the assessment session, Module 2 specifically targets intolerance of uncertainty and increasing worry awareness. As some patients can find the imaginal exposure worry scripts [3] too distressing, in the Timulak et al. [2] study, we introduced exposure to ‘simple still images’ without scripts, which increase in detail and complexity with habituation, until patients are able to tolerate complex scripted scenes. Still images merely involve patients describing their feared scene and stopping when they reach a ‘hot-spot’ (i.e., an image that raises notable anxiety). At this point they are guided to hold this image, ‘like looking at a photograph’, while rating their anxiety to the point of habituation. In the case series (Chigwedere & Moran, under review), we only referred to imaginal exposure to the future as a way of demonstrating the effects of worry.

Uncertainty Tolerance Training (UTT)

We have called sitting with uncertainty triggers and associated uncertainty to the point of tolerance UTT. This is because the objective is not exposure and habituation but increased tolerance and acceptance of the sense of not knowing, not unlike inhibitory learning [35]. In each session, patient and therapist collaboratively identify a recent worry event and the environmental trigger, with which the patient imaginally engages non-judgmentally, resisting the urge ‘flee into a quest for certainty’ by worrying. Specific events are identified and engaged with as homework. Once adept at holding the image, patients are introduced to the idea of an uncertainty statement, making the uncertainty an explicit component of the UTT. As the patient becomes adept at identifying worry triggers and uncertainty, they are encouraged to increasingly practice with live events. We hypothesize that tolerance of the uncertainty triggers in the current environment reduces fear and the flight into a ‘quest for certainty’ (i.e., worry). Some patients who have practiced both imaginal exposure and UTT, have described imaginal exposure as bearing similarities to worry, which is hypothetical and avoids the current uncertainty. As patients become more skilled with UTT, a problem-solving component is introduced. This involves therapists and patients collaboratively identifying what is known, (e.g. “I know my wife is walking away”) and not known (e.g. “I don’t know what she is thinking”). The therapist then asks “You know… but you don’t know …. What options do you have, as you look at this?” The patient then practices learning to problem solve the uncertain event, not a future hypothesis.

Module 3: Contextualizing intolerance of uncertainty and worry: This module aims to help clients to hypothesize the possible developmental contexts of their worry. The hypothesis is that many important cognitions have roots in developmental experiences. Cognitive work has a function of testing developmentally as tests of developmentally acquired schema-based messages, identifying and developing healthier alternatives. Individuals with GAD have a tendency to worry and ruminate, so we encourage the use imagery and experiential methods. The aim of this module is to contextualise the worry, taking advantage of the preceding work. To do this, current or worry events are first engaged with as in UTT, identifying cognitive and affective states. Affect is then engaged with and traced back, using it as a link to childhood memories of similar experiences. Once such memories are identified, imagery rescripting work is employed, and collaboratively linked back to current worry, either experientially through rescripting or in reflection. Besides rescripting developmental events, we have found this to be a powerful way of identifying different levels of emotionladen cognitions, including their helpful alternatives (Chigwedere & Moran, in preparation). Learning from rescripting work is a useful way of identifying schemas or core beliefs and to develop hypotheses to be tested and challenged through standard CBT techniques (e.g. behavioural experiments, surveys and exposure). We have also developed a diary sheet to help patients to identify ways in which they may have reinforced the schema/core beliefs through the years.

Module 4: Problem-solving: If worry is merely a dysfunctional attempt at problem-solving due to lack of a credible alternative, offering a helpful alternative may reduce reliance on the dysfunctional one. Problem-solving has been described as a response to obstacles to life goals, which are for a time, insurmountable with customary methods [29]. It has been used as a standalone or component therapeutic technique. Therapists engage in problem solving using the 6 stages described by Dugas and Robichaud [3]. These include 1) problem definition, 2) choosing a target problem, 3) agreeing on goals, 4) solution generation, 5) choosing a solution, 6) establishing the necessary steps to implement the solution, 7) solution implementation...” 8) evaluation of the effectiveness of the solution. This is a more thorough skills training approach than that used as a component of UTT in Module 2.

Module 5: Mindfulness: UTT may be reminiscent of ‘mindfulness’, In mindfuless, one engages non-judgmentally with a neutral anchor that is not problem specific (e.g. the breath), with profound impacts. However, a neutral anchor may not engage the schema. The UTT ‘anchor’ (i.e. the image and uncertainty statement) may be a schema-related CS. In non-judgemental engagement with the CS one may learn that it can be tolerated and reappraised. It is not necessary to continue such focused daily UTT or imaginal exposure ad infinitum, making mindfulness an appropriate maintenance and relapse prevention technique. Thus, once GAD and worry symptom improvement are achieved, standard mindfulness is introduced.

Summary

We describe the IoU model but with important adaptations, including a focus on current triggers of uncertainty rather than the future focused worry, as well as making the uncertainty explicit. We offer an alternative rationale for worry as a premonition bias, due to its association with schemas and developmental events. We propose a three-phase description of the worry process, with the environmental trigger as an important target for intervention. Our treatment approach incorporates this hypothesis within the standard, evidence-based approach but offering an alternative explanation, which potentially brings new treatment possibilities. The contextual module potentially offers each individual an explanation of the why and how of their own worry. Though much of what we have proposed is based on clinical observation and literature, it has some evidence of effectiveness through its application in a research study and a case series. This makes this description paper important for others who may wish to apply this approach clinically as either a standalone or adjunctive approach.

References

- Dugas MJ, Freeston MH, Ladouceur R (1997) Intolerance of uncertainty and problem orientation in worry. Cognitive Therapy and Research 21(6): 593-606.

- Timulak L, Keogh D, Chigwedere C, Wilson C, Ward F, et al. (2018) Generalised anxiety disorder: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 19(1): 506.

- Dugas MJ, Robichaud M (2007) Practical clinical guidebooks. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: From science to practice. Routledge, London, UK.

- American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (5th edn), Washington, DC, USA.

- American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (5th edn), Washington, DC, USA.

- World Health Organization (1990) International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. 10th revision, edition. World Health Organization. Geneva. Switzerland.

- World Health Organization (2010) International Classification of diseases and related health problems. World Health Organization. Geneva. Switzerland.

- Wehry AM, Baum BK, Hennelly MM, Connolly SD, Strawn JR (2015) Assessment and treatment of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Curr Psychiatry Rep 13(2): 99-110.

- Gersh E, Hallford DJ, Rice SM, Kazantzis N, Gersh H, et al. (2017) Systematic review and meta-analysis of dropout rates in individual psychotherapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 52: 25-33.

- Borkovec TD, Costello E (1993) Efficacy of applied relaxation and cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 61(4): 611-619.

- Borkovec TD, Newman MG, Pincus AL, Lytle R (2002) A component analysis of cognitive-behavioral therapy for generalized anxiety disorder and the role of interpersonal problems. J Consult Clin Psychol 70(2): 288-298.

- Borkovec TD (1994) The nature, functions and origins of worry. In: Davey GC, Tallis F (Eds.), Worrying, perspectives on theory, assessment and Treatment. Wiley, Chichester, UK, pp. 5-33.

- Borkovec TD, Alcaine O, Behar E (2004) Avoidance theory of worry and generalized anxiety disorder. In: Heimberg RG, Turk CL, Mennin DS (Eds.), Generalized anxiety disorder: Advances in research and practice. Guilford Press, New York, USA, pp. 77-108.

- Wells A (1995) Meta-cognition and worry: A cognitive model of generalized anxiety disorder. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy 23(3): 301-320.

- Wells A (2000) Emotional disorders and metacognition. Wiley, Chichester, UK.

- Mennin DS, Heimberg R, Turk CL, Fresco DM (2002) Applying an emotion regulation framework to integrative approaches to generalized anxiety disorder. Clinical psychology: Science and Practice 9: 85-90.

- Alvarez RP, Chen G, Bodurka J, Kaplan R, Grillon C (2011) Phasic and sustained fear in humans elicits distinct patterns of brain activity. Neuroimage 55(1): 389-400.

- Arntz A, Weertman A (1999) Treatment of childhood memories: Theory and practice. Behaviour Research and Therapy 37(8): 715-740.

- Baddeley A (1996) Your memory. A user’s guide. Prion, London, UK.

- Beck AT, Haigh EAP (2014) Advances in cognitive therapy and theory: The generic model. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 10: 1-24.

- Borkovec TD, Hu S (1990) The effect of worry on cardiovascular response to phobic imagery. Behav Res Ther 28(1): 69-73.

- Borkovec TD, Roemer L (1995) Perceived functions of worry among generalized anxiety disorder subjects: Distraction from more emotional topics? J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 26(1): 25-30.

- Bretherton I (1987) New perspectives on attachment relationships. In: Osofsky J (Ed.), Handbook of infant development, (2nd ed), New York. Wiley, USA, pp. 1061-1100.

- Brewin CR, Holmes EA (2003) Psychological theories of posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinical Psychology Review 23(3): 339-376.

- Young J, Klosko JS, Weishaar ME (2003) Schema therapy. A practitioner’s guide. New York, USA.

- Brewin CR, Dalgleish T, Joseph S (1996) A dual representation theory of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Review 103(4): 670-686.

- Buhr K, Dugas MJ (2002) The intolerance of uncertainty scale: Psychometric properties of the English version. Behaviour Research and Therapy 40(8): 931-946.

- Caplan G (1961) An approach to mental health. Grune and Stratton, New York, USA.

- Cassidy J (1995) Attachment and generalized anxiety disorder. In: Toth DCS (Ed.), Rochester symposium on developmental psychopathology: Emotion, cognition and representation. University of Rochester Press, USA, pp. 343-370.

- Carpenter AC, Schacter DL (2017) Flexible retrieval: When true inferences produce false memories. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn 43(3): 335-349.

- Chigwedere C, Moran J (2018) A novel three-stage model of Intolerance of uncertainty in GAD: A case series illustrating the concepts of current uncertainty and premonitions bias.

- Clark GI, Rock AJ,Clark LH, Lyon MK (2020) Adult attachment, worry and reassurance seeking: Investigating the role of intolerance of uncertainty. Clinical psychologist 24(3): 294-305.

- Colonessi C, Draijer EM, StamsGJJM, Vander Bruggen CO, Bögels SM, et al. (2011) The relationship between insecure attachment and child anxiety. A meta-analytic review. J Clin Child Adolescent Psychology 40(4): 630-645.

- Conway MA, Pearce PCW (2000) The construction of autobiographical memories in the self-memory system. Psychological Review 107(2): 261-288.

- Craske MG, Treanor M, Conway C, Zbozinek T, Vervliet B (2014) Maximising exposure therapy: An inhibitory learning approach. Behav Res Ther 58: 10-23.

- Davey GCL, Jubb M, Cameron K (1996) Catastrophic worrying as a function of changes in problem solving confidence. Cognitive Therapy and Research 20: 333-344.

- Dugas MJ, Gagnon F, Ladouceur R, Freeston MH (1998) Generalized anxiety disorder: A preliminary test of a conceptual model. Behaviour Research and Therapy 36(2): 215-226.

- Dzurilla TJ, Nezu A (1980) A study of the generation of alternatives process in social problem solving. Cognitive Therapy and Research 4(1): 67-72.

- D Zurilla TJ, Nezu AM (1999) Problem-solving therapy: A social competence approach to clinical intervention (2nd edn), Springer, New York, USA.

- Ehlers A, Clark DM (2000) A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy 38(4): 319-345.

- Goode TD, Ressler RL, Acca GM, Miles OW, Maren S (2019) The bed nucleus of the stria terminalis regulates fear to unpredictable threat signals. Neuroscience 8: e46525.

- Hamidpour H, Dolatshai B, Shahbaz AP, Dadkhah A (2011) The efficacy of schema therapy in treating women’s generalized anxiety disorder. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology 16(4): 420-431.

- Hawton K, Kirk J (1989) Problem-solving. In: Hawton K, Salkovskis PM, Clarke DM (Eds.), Cognitive behaviour therapy for psychiatric problems. A practical guide. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

- Hoyer J, Beesdo K, Gloster AT (2009) Worry exposure vs applied relaxation in generalized anxiety disorder. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics 78(2): 106-115.

- Hözel BK, Hoge EA, Greve DN, Gard T, J David Creswell, et al. (2013) Neural mechanisms of symptom improvements in generalized anxiety disorder following mindfulness training. Neuroimage Clin 25(2): 448-458.

- Ladouceur R, Gosselin P, Dugas MJ (2000) Experimental manipulation of intolerance of uncertainty: A study of a theoretical model of worry. Behaviour Research and Therapy 38(9): 933-941.

- Leahy RL (2019) Introduction: Emotional schemas and emotional schema therapy. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy 12: 1-4.

- Maren S (2001) Pavlovian fear conditioning. Annu Rev Neurosci 24: 897-931.

- Mason O, Platts H, Tyson M (2005) Early maladaptive schemas and adult attachment in a UK clinical population. Psychology and psychotherapy: Theory, research and practice 78(4): 549-564.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2010) Supporting adult carers.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2011) Generalised anxiety disorder (NICE Quality Standard CG113).

- Newman MG, Llera SJ (2011) A novel theory of experiential avoidance in general anxiety disorder. A review and synthesis of research of research supporting a contrast avoidance model of worry. Clin Psychol Rev 31(3): 371-382.

- Pavlov IP (1927) Conditioned Reflexes: An investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex. Oxford University Press, London, UK.

- Radley JJ, Sawchencko PE (2011) A common substrate for prefrontal and hippocampal inhibition of the neuroendocrine stress response. J Neurosci 31(26): 9683-9695.

- Radley JJ, Johnson SB (2017) Anteroventral bed nuclei of the stria terminalis neurocircuitry: Towards an integration of HPA axis modulation with coping behaviors. Psychoneuroendocrinology 31(26): 89:239-249.

- Riskind JH, Williams NL (2005) The looming cognitive style and general anxiety disorder. Distinctive danger schemas and cognitive phenomenology. Cognitive Therapy and Research 29(1): 7-27.

- Schauer M, Ebert T (2010) Dissociation following traumatic stress: Etiology and treatment. Zeitschrift f r Psychologie/Journal of Psychology 218(2): 109-127.

- Shariati S, Shariatnia K, Ghasemian D (2014) Correlation between anxiety and early maladaptive schemas on female students of third year of high school Minudhasht. European Journal of Experimental Biology 4(2): 198-203.

- Sidley GL, Whittaker K, Calam R, Wells A (1997) The relationship between problem. Solving and autobiographical memory I parasuicide patients. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy 25(2): 195-202.

- Shorey RC, Elmquist J, Anderson A, Stuart GL (2016) The relationship between early maladaptive schemas, depression and generalized disorder among adults seeking residential treatment for substance use disorder. J Psychoactive Drugs 47(3): 230-238.

- Tromp DPM, Grupe DW, Oathes DJ, McFarlin DR (2012) Reduced structural connectivity of a major frontolimbic pathway in generalized anxiety disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 69(9): 925-934.

- Williams JMG (1997) Cry for pain: Understanding suicide and self-harm. Harmondsworth, Penguin Books, Middlesex, UK.

- Williams JMG, Teasdale JD, Segal ZV, Soulsby J (2000) Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy reduces overgeneral autobiographical memory in formerly depressed patients. J Abnorm Psychol 109(1): 150-155.

- Wilson C (2020) Understanding children’s worry: Clinical, developmental, and cognitive psychological perspectives. Routledge, London, UK.

- Wilson CE, Hughes C (2011) Worry beliefs about worry and problem solving in children. Behav Cogn Psychother 39(5): 507-521.

- Wright CJ, Clark GI, Rock AJ, Coventry WL (2017) Intolerance of uncertainty mediates the relationship between adult attachment and worry. Personality and Individual Differences 112(1): 97-102.

- Zeithamova D, Dominick AL, Preston AR (2012) Hippocampal and ventromedial-prefrontal cortex activation during retrieval mediated learning supports novel inference. Neuron 75: 168(1)-179.

© 2021 Chigwedere C, This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)