- Submissions

Full Text

Psychology and Psychotherapy: Research Studys

Helping Physicians Help Themselves: Nature Vs. Nurture

Alan H Rosenstein*

Consultant in Physician Behavioral Management, Canada

*Corresponding author: Alan H Rosenstein, Consultant in Physician Behavioral Management, Canada

Submission: August 28, 2020Published: November 25, 2020

ISSN 2639-0612Volume4 Issue3

Helping Physicians Help Themselves: Nature Vs. Nurture

Working as a physician has always been a stressful occupation. It starts with the competition of getting into medical school, then comes the non-relentless time demands of dedication, study, hazing, and on call fatigue throughout medical training, and then the never ending demands of clinical practice in today’s complex high pressure medical environment. We have all gone through it and the majority of us make it through recognizing the price we had to pay for becoming a physician. It’s always been that way. Then about 20 years ago things began to change. Medicine became a business and dollars seemed to overtrump quality. The Government and private insurance companies introduced contract based “managed” care and implemented a series of utilization controls “telling” physicians what they can and cannot do.

Ten years ago, they began to introduce programs focusing on paying for “value-based care” by implementing a series of performance metrics holding providers accountable for their outcomes financially penalizing the poorer performers. Then came the introduction of new technologies and the electronic medical record (EMR) which interfered with the physician’s customary care process and flow and added a new series of new non-clinical responsibilities taking time away from direct face to face patient care. Things were getting worse and we began to see obvious evidence of physician frustration, stress, and burnout which began to adversely affect their attitudes toward medical practice. The forces were there but they were hidden in silence. Then came a landmark study published in The Mayo Clinic Proceedings which gave the first comprehensive report documenting the significant amount of stress and burnout affecting more than 50% of the surveyed physicians [1]. Follow up studies have shown that nothing has changed, but there has been a notable cause for action [2,3]. Now with the advent of the COVID pandemic things have actually gotten worse. Issues related to care delivery, patient flow, exposure, safety, protective support, and financial survival have taken a central stage in the changing dynamics of health care practice [4]. So how can we more effectively address this serious issue?

Causes

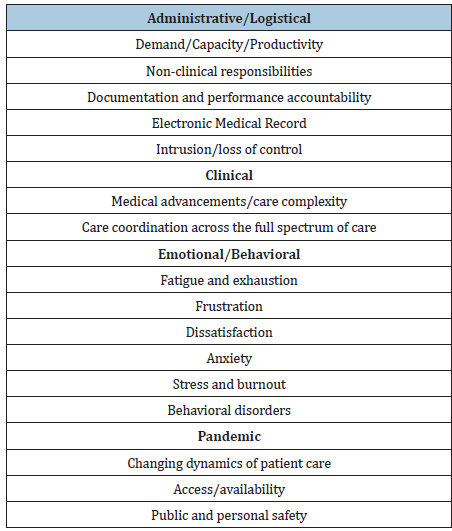

The first thing we need to consider are the causes. We can classify the causes into four categories: Administrative, Clinical, Behavioral, and Pandemic (Table 1). From the administrative perspective we look at problems related to over demand, over extension, over scheduling, time requirements to complete documentation and other non- clinical responsibilities, mandates for compliance with the electronic medical record, and a general sense of loss of autonomy and control. From the clinical perspective we need to look at the influx of new medical breakthroughs and the growing complexities of comprehensive care delivery which are changing roles and responsibilities forcing physicians to take on more responsibility and accountability for monitoring and reporting on full spectrum care and population management. From the emotional perspective we need to look at exhaustion, compassion fatigue, growing frustration and dissatisfaction, and the physical and emotional consequences of stress and burnout often resulting in behavioral disorders. From the pandemic perspective it’s changing the model and dynamics for health care delivery raising concerns about access and availability and public and personal safety.

Table 1: Sources of physician anxiety, stress, and burnout.

Recommendations

In regard to the administrative issues, organizations need to become more aware of and be more sensitive to physician concerns about external intrusion, excessive demands, time spent on non- clinical activities, and the frustrations with the electronic medical record. They must be willing to readjust schedules, ease capacity and productivity requirements, try to minimize their non-clinical responsibilities, and provide additional training and support to help physicians better accommodate to documentation requirements and the electronic medical record. In regard to clinical issues, utilize Nurse Practitioners or Physician Assistants to handle everyday matters and free the physician up to focus on more complex medical issues. Utilize Care Managers to help them (and their patients) better negotiate all the intricacies of the health care environment. In regard to the behavioral issues this is a much more complex issue that will require commitment from both the health care organization and the physician themselves and will be discussed in more detail below. In regard to the immediate issues posed by the Covid epidemic, organizations need to listen to physician concerns, take efforts to assure their safety and the safety of others, and provide the necessary technical and emotional support to help them get through this crisis.

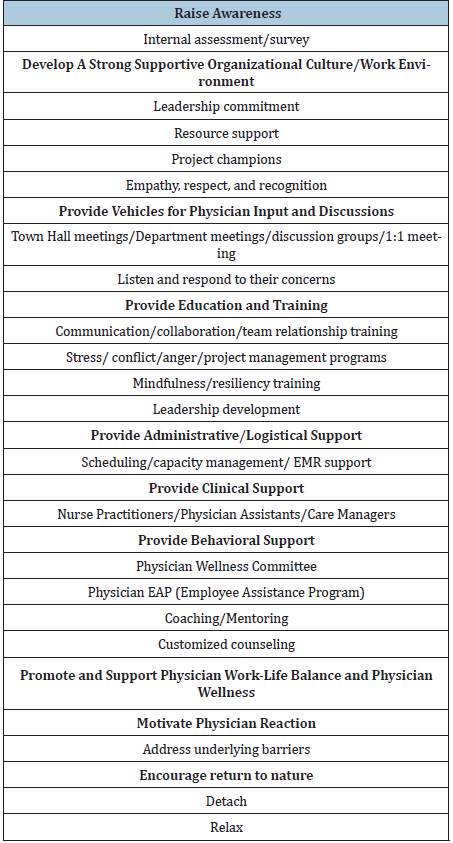

The organization plays a pivotal role in supporting physician wellness. This requires a multistep process that starts with leadership empathy and commitment, the willingness to provide resource support, and the need to cultivate a positive workplace environment [5]. The organization should provide education and training on such topics as improving communication and relationship skills, enhancing leadership development, stress management, conflict management, Mindfulness, and Resiliency. They should also offer additional personalized services that include mentoring and coaching. In some cases, they may have to provide more focused behavioral interventions or counseling. But the organizations can only do so much. At this point it is dependent on the individual physician to take action. There are significant barriers that prevent this from happening [6].

Barriers

The first barrier is physician awareness. At the forefront physicians don’t want to admit that they are stressed. Part of the problem is their stoic nature. They are so compelled by responsiveness to patient concerns that they overlook any impact it may be having on themselves. They feel guilty if they do [7]. If they do recognize that they’re stressed they rationalize non- action by stating that they’ve been working under stress all their lives and they can handle it. Many physicians feel that they don’t have the time for these types of services. If they were to consider asking for help many of them don’t even know where to go. They have concerns about confidentiality and fears about receiving a diagnosis that might affect their competency, medical privileges, and licensure [8].

Solutions

The first solution is to be sensitive to the physician barriers [9]. Focus on the goal of the services being offered is to help the physician thrive in their practice. Show empathy and concern. Listen to what they have to say. Let them know that you realize that they are an overextended precious resource and show respect and gratitude for everything that they do. Assure confidentiality. Provide accommodating services that can fit in with their hectic schedule. The second step is motivation. The goal here is to restore their passion, joy, and purpose for medicine by continually reminding them of what they do and what they have accomplished in their career [10].

Offer education and training services in relationship building, emotional intelligence, stress management, mindfulness, and resiliency, but recognize that it can only go so far [11,12]. Promote physician wellness. From a logistical perspective this can be done by encouraging rest, relaxation, promoting work- life balance by reducing care responsibilities, mandating time off, having in-house exercise facilities, providing gourmet meals, child care, and laundry services for physicians on-call, or providing tickets for recreational activities. From a behavioral perspective there has been a resurgence of the Physician Wellness Committee which are now taking a more pro-active hands on approach in trying to help physicians better adjust to the pressures of medical practice. Several organizations have introduced a new role of Chief Wellness Officer whose main responsibilities are to promote health and wellness in the medical staff [13]. A more detailed set of recommendations is provided in Table 2; [14].

Table 2: Recommended strategies to reduce physician frustration, anxiety, stress, and burnout.

The Real Solution

For any of these programs to really work it will require the physician to detach from their day to day responsibilities. They need to recognize the importance of taking time away from the office, turning off their electronic devices, and getting back in touch with the sounds, sights, smells, and touches of nature. In her book The Nature Fix author Florence Williams stresses the importance of detaching and disconnecting and making it a priority to take time to get outside and visit with the surroundings [15]. Allow your sensory organs an opportunity to explore the world around you rather than being driven by the analytical thoughts and distractions that rule the day. Think about the value of being happy rather than the consequences of being overwhelmed by negativity and a never-ending list of things to do. It is OK to postpone or even say no. Walking outside in nature lessens the chance of being consumed by negative thoughts. Equally important is the recognize the importance of human interaction and to avoid isolation and withdrawal. [16]. In Japan and Korea, the governments have taken this concept one step further by investing millions of dollars in developing restorative healing forests designed to provide rest, comfort, and relaxation to those who utilize these services [17]. Benefits can be gained by committing as little as five hours a month in this type of environment. For those of you who are unable to make it to the forest, try gardening [18]. If nothing else just try to make it outside (Table 3).

Table 3: Nature’s Pyramid.

Conclusion

Physicians just want to be good physicians but too many things are getting in the way. Growing stress and burnout have led to frustration, dissatisfaction, disillusionment, and emotional or physical impairment, where many physicians have lost their purpose and are beginning to look for other career opportunities or choose early retirement. We need to recognize that most physicians won’t take action on their own, so we need proactive support from friends, family, colleagues, and the institutions and organizations that the physician is associated with. Give them an opportunity to comfortably discuss their issues rather than bearing it alone. We need to provide personalized confidential support services designed specifically to help the physician succeed. We need to help motivate and provide structure for change. Remind them of what they do. We need to help them periodically escape the stresses of medical practice and learn how to enjoy the world around them. Physicians need to understand and appreciate the need for rest and relaxation and the importance of getting away from all the turmoil. It can be as simple as taking a walk outside, detaching from work, and allowing your senses to fill you up with joy. It’s not a big commitment. 20 minutes a day can do the job. You just have to recognize how important it is and make the commitment to make it happen.

References

- Shanafelt T, Hasan O, Dyrbye L, Sinsky C, Satele D, et al. (2016) Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general us working population 2011-2014. Mayo Clin Proc 91(2): 1600-1613.

- Shanafelt T, West C, Sinsky C, Satele D, Trockel M, et al. (2019) Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general us working population between 2011-2017. Mayo Clin Proc 94(4): 1681-1694.

- Abbott B (2020) Physician burnout is widespread, especially among those in midcareer. The Wall Street Journal.

- Shanafelt T, Ripp J, Trockel M (2020) Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA 321(21): 2133-2134.

- Carayon P, Cassel C, Dzau V (2019) Improving the system to support clinician well-being and provide better patient care. JAMA 322(2): 2165-2166.

- Feist Je, Feist Jo, Cipriano P (2020) Stigma Compounds the consequences of clinician burnout during COVID-19: A Call to action to break the culture of silence. National Academy of Science.

- Blum L (2019) Physician’s goodness and guilt: Emotional challenges of practicing medicine. JAMA Intern Med 179(5): 607-608.

- Arnhart A, Privitera M, Fish E, Young A, Arthur S Hengerer, et al. (2019) Physician burnout and barriers to care on professional applications. J Leg Med 39(3): 235-246.

- Rosenstein A (2019) Hospital administration response to physician stress and burnout. Hosp Pract 47(5): 217-220.

- Schwenk T (2020) What does it mean to be a physician? JAMA 323(11): 1037-1038.

- Gorell A (2020) Addressing burnout-focus on systems, not resilience. JAMA Network Open Psychiatry 3(7).

- Card A (2018) Physician burnout: Resilience training is only part of the issue. Annals of Family Medicine 16(3): 267-270.

- Ripp J, Shanafelt T (2020) The health care chief wellness officer: What the role is and is not. Acad Med 95(9): 1354-1358.

- Rosenstein A (2017) Addressing physician stress and burnout: Impact, implications, and what we need to do. Journal of Psychology and Clinical Psychiatry 7(4): 1-3.

- Williams F (2018) The Nature Fix Norton W.W. and Company New York, NY, USA.

- Southwick S, Seacreast F (2020) The loss of social connectedness as a major contributor to physician burnout: Applying organizational and teamwork principles for prevention and recovery. JAMA Psychiatry 77(5): 449-450.

- https://healingforest.org/2017/03/26/7-healing-forests-from-japan/

- Yasin H (2018) I’ll be out in the garden destressing NY Times.

© 2020 Alan H Rosenstein, This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)