- Submissions

Full Text

Psychology and Psychotherapy: Research Studys

Importance and Advantages of Telepsychiatry in Mental Health During COVID 19 Pandemic

Shamil Ul Haque AbbasyM*

Department of Psychiatry, Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Pakistan

*Corresponding author: Shamil Ul Haque Abbasy M, Department of Psychiatry, Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Pakistan

Submission: September 22, 2020Published: October 06, 2020

ISSN 2639-0612Volume4 Issue2

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has unsettled the arrangement of mental health administrations. In reaction, policymakers, directors, and suppliers have taken striking steps toward empowering telepsychiatry to bridge this sudden crevice in care for our most vulnerable populations. With fast deregulation and selection of this method of care, cautious consideration of issues related to policy and execution is crucial to maximize its viability and reduce unintended results. Although the COVID-19 crises put the healthcare framework under strain, it prepares for a lasting shift in not only how care is delivered but also our convictions around the system’s capacity for swift, innovational change.

Introduction

The current COVID-19 pandemic has made unexpected challenges in giving quality care for mental health patients. Along with quick endeavors to contain the spread of the virus through social distancing, healthcare systems and providers must adapt just as quickly to guarantee the progression of care for populations are at a higher chance of neglect because of their mental illness. Luckily, existing telepsychiatry technology shows promising ability to bridge this sudden gap in care even more so than telemedicine, as psychiatric assessments are more to a great extent dependent on the interview, and less so on physical examination. However, there are some barriers to this widespread enactment which we aim to illustrate here. These include longstanding policies concerning reimbursement, access, and practical issues faced by hospitals, clinics, and providers still unskilled to deliver care through this method. Despite the difficulties and instability, this emergency presents an opportunity to not only improve our healthcare system’s response to future necessities but also to remodel its approach to increasing access to care for years to come. In this mini review, we aim to discuss about advantages and need for this type of model, recent policy changes for telemedicine, role of telepsychiatry in child and adolescent psychiatry and the future of telemedicine and required assessments.

What is Telepsychiatry?

Just like Telemedicine-Telepsychiatry can involve direct interaction between a psychiatrist and the patient. It also encompasses psychiatrists supporting primary care providers with mental health care consultation and expertise. Mental health care can be delivered in a live, interactive communication. It can also involve recording medical information (images, videos, etc.) and sending this to a distant site for later review. CMS has long prioritized telemedicine innovation, but COVID-19’s emergence in the U.S. prompted us to drastically accelerate our efforts [1].

The advantages and need for telepsychiatry

Video-based telepsychiatry helps meet patients’ needs for helpful, reasonable and readily accessible mental health services. It can assist patients in a number of ways, such as:

1. Improve access to mental health specialty care that might not otherwise be available (e.g., in rural areas).

2. Bring care to the patient’s location. 3. Help integrate behavioral health care and primary care, leading to better outcomes. 4. Reduce the need for trips to the emergency room. 5. Reduce delays in care. 6. Improve continuity of care and follow-up. 7. Reduce the need for time off work, childcare services, etc. to access appointments far away. 8. Reduce potential transportation barriers, such as lack of transportation or the need for long drives. 9. Reduce the barrier of stigma.

Whereas a few individuals may be hesitant or feel ungainly talking to an individual on a screen, experience shows most individuals are comfortable with it. A few individuals may be more relaxed and willing to open up from the comfort of their home or a nearby office. This will probably be less of an issue as individuals become more commonplace and comfortable with video communication in daily life. Telepsychiatry allows psychiatrists to treat more patients in distant locations. Psychiatrists and other clinicians need to be licensed in the state(s) where the patient they are working with is located. State licensing boards and legislatures view the location of the patient as the place where “the practice of medicine” occurs. Although telepsychiatry has the disadvantage of the patient and psychiatrist not being in the same room, it can create enhanced feelings of safety, security and privacy for many patients [1].

Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a surge of patients with first episode of psychiatric disorders like depression, anxiety and even acute psychosis. There have also been reports of acute exacerbation and relapses of patients with preexisting psychiatric diagnoses [2]. Due to all these aforementioned emergencies, there is a dire need of escalation for the development of proper systemic and infallible telepsychiatry structure. Fortunately, the ensuing lockdown in many countries has opened up vistas of teleconsultation and various agencies have proposed telepsychiatry guidelines within weeks.

Recent Changes in Policy for Telemedicine

Recent growth of telepsychiatry, though outpacing telemedicine, has been modest partly due to difficulty in achieving comprehensive parity-insurance coverage and reimbursement equal to that of in-person care. The finding that state mandates for parity have supported growth of telepsychiatry but not telemedicine underscores the unique relevance parity has to our field. However, continued low overall utilization of telepsychiatry despite growing reimbursement suggests other factors are also to blame (Barnett et al. 2018; Douglas et al. 2017). In light of the social distancing employed to contain the growing pandemic, limiting the ability of patients to connect with healthcare, policymakers have taken bold steps toward both promoting parity and lifting restrictions around licensing and encounters [3]. On March 17, 2020, the U.S. Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services removed the requirement for patients to travel to an “originating site” to receive care remotely (Medicare Telemedicine Health Care Provider Fact Sheet 2020). In parallel, the Drug Enforcement Agency authorized the prescribing of controlled substances without an initial face-to-face encounter (DEA’s response to COVID-192020) and the Department of Health and Human Services waived penalties for the use of non-HIPAA compliant communication tools (Medicare Telemedicine Health Care Provider Fact Sheet 2020), including popular applications like FaceTime or Zoom. Some governors have issued orders easing licensing requirements to permit remote encounters across state lines as well as mandating parity. State Medicaid programs and private insurers also are starting to join this concerted effort to quickly dismantle some of the traditional obstacles telemedicine and telepsychiatry have faced (The Efficacy and Expansion of Telemedicine to Meet the Growing COVID-19 Pandemic2020) [3].

Role of Telemedicine in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Parents’ Satisfaction

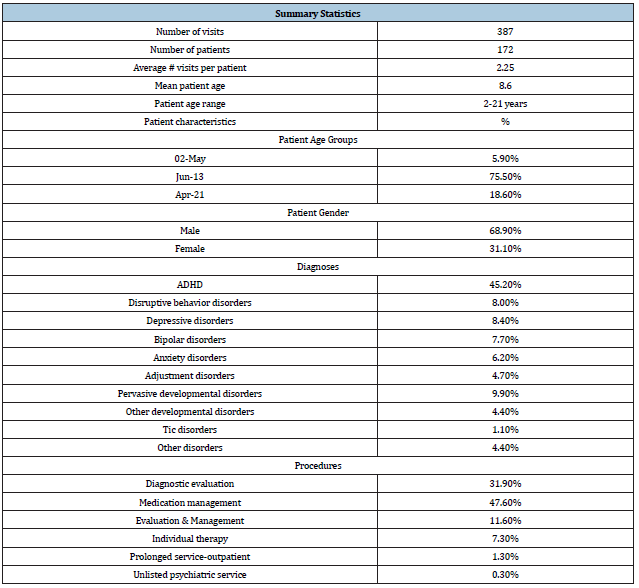

In light of recent events, COVID-19 has affected urban and rural populations equally to seek medical and psychiatric care. Among school-going children and adolescents, the suspension of the school curriculum and daily activities has impacted negatively on their mental health. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among children, and adolescents living in rural communities are comparable to that in urban areas, but the distribution of psychiatric services are not, because valuable psychiatric resources are reserved for chronically mentally ill adults, and evidencebased treatments for children are not widely disseminated outside of urban areas. Thus, most youth who have psychiatric disorders and who live in rural areas are underserved and their impairments affect multiple domains of functioning.4 Here we evaluate a previously built telepsychiatry service model illustrated by Myers et al. [4] to deliver evidence-based care to children and adolescents living in 4 diverse nonmetropolitan communities across Washington State. The findings regarding utilization and satisfaction with the care rendered through this service included reports of satisfaction of adults with their telepsychiatric care along with a few reports of satisfaction with care rendered to children and adolescents. Therefore, this study fills an important need in describing parents’ satisfaction with their children’s telepsychiatric care. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Children’s Hospital and Regional Medical Center (CHRMC) in Seattle. Table 1, as illustrated by Myers et al. [4] thoroughly summarizes demographic, clinical, and utilization data. During the study year, 387 telepsychiatry encounters were provided for 172 patients across the 4 sites, averaging 2.25 encounters per patient. Patients ranged in age from 2 to 21 years old, with a mean age of 8.6 years old, predominantly boys. These demographics are consistent with our own prior experience as well as with those described in usual outpatient mental health clinics.

Table 1: Demographic and clinical characteristics of children and adolescents receiving telepsychiatry services.

Of the 387 psychiatric encounters, 248 surveys were completed for an overall response rate of 64%. Responses on each survey item for all patients, patient age, and type of clinic visit are shown in Table 2. As shown, 11 of the 12 items show mean overall scores above 4.0 on a 5-point scale across patient age. Item 8, “My child would not have received services of a specialist without telemedicine,” showed the lowest rating, suggesting that parents perceived that telepsychiatry was not their only option and that they would have sought care elsewhere. However, most of these youth had been severely symptomatic for a long time and had not sought such alternative services. Overall, across the 3 developmental groups, several items reached statistical significance (items 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12) or a trend to significance (items 1, 5, 9). Parents of adolescents generally endorsed lower satisfaction with their children’s care (items 6, 7, 9, 10, 11), whereas parents of school-aged children generally endorsed greater satisfaction with their children’s care (items 6, 8, 9, 11, 12). A comparison of new versus follow-up visits showed that parents were highly satisfied with both types of appointments. There were significant differences on 4 items (1, 7, 8, 9), in each case indicating higher ratings for follow-up visits. These significant items suggest greater comfort with this medium at return appointment (item #1), appreciation of seeing a psychiatrist sooner (item #7), recognition that without telepsychiatry the child may not have seen a specialist (item #8), and parents’ optimism that their children would receive the services they need due to telepsychiatry (item #9). On no item did parents indicate significantly lower satisfaction at return appointment [5].

Table 2: Parent-reported satisfaction with telepsychiatry by patient age groups and visit type (n=248).

aMann-Whitney rank sum test; bkrushal-Wallis rank sum test. bMann-Whitney test. *p<0.05. **p<0.01. ***p<0.001.

The Future of Telemedicine and Required Assessments

The changes in telemedicine regulations in response to COVID-19 have been groundbreaking, but it is unclear whether the recent prescription, licensure, and reimbursement changes will revert to their pre-COVID-19 rules when federal and state COVID-19 emergency declarations end. Will the authorities do this abruptly, or will there be a transition period? Will legislatures use a process to consider whether to make these permanent going forward? The field of psychiatry, working with our colleagues in the wider field of medicine, has an opportunity now to proactively look at the current telemedicine regulations and begin advocating for their longerterm maintenance. If we fail to do so, we run the risk of state and federal legislatures reinstituting barriers to telepsychiatry that are ultimately harmful to patient care. Our priority now is to support our patients, systems, and colleagues as we weather the current storm.

The regulatory and system changes wrought by the COVID-19 crisis present the opportunity for the field to gather lessons learned to strategically shape the post-COVID-19 world of psychiatry and telepsychiatry. This work could usher in a golden era for technology in psychiatry in which we are able to harmonize the benefits of telepsychiatry and virtual care while maintaining the core of our treatment: that of human connectedness. First, it is important to assess whether the mode of telehealth service delivery is clinically appropriate and safe for patients, as compared to an in-person visit. For example, during the public health emergency, CMS expanded certain telemedicine services to both new and established patients, where previously those services were limited to patients who had an established relationship with the practitioner. CMS took this action to make these services as widely available as possible given the need to reduce exposure risks for practitioners and patients. As the health care system enters a new normal, it is important to consider whether allowing people with particularly acute needs to be seen by a clinician for the first time via telemedicine, instead of in-person, will result in the best possible outcomes. Second, we need to assess the Medicare payment rates for telehealth services. During the public health emergency, Medicare paid the same rate for a telehealth visit as it would have paid for an in-person visit, given the unique circumstances of the pandemic. Outside the pandemic, by law Medicare usually pays for telehealth services at rates similar to what professionals are paid in the hospital setting for similar services. Further analysis could be done to determine the level of resources involved in telehealth visits outside of a public health emergency, and to inform the extent to which payment rate adjustments might need to be made. For example, supply costs that are typically needed to enable safe in-person care (for, e.g., patient gowns, cleaning, or disinfectants) and built into the in-person payment rate are not needed in a telehealth visit. On the other hand, there are new processes that clinicians must create for telehealth visits, with associated costs. Lastly, it is vital that beneficiaries and taxpayer dollars are protected from unscrupulous actors. As more health care providers use telehealth to treat beneficiaries, CMS is examining our data from many angles. We are monitoring program integrity implications such as practitioners who may be offering shorter telehealth visits with patients to maximize payment or billing more visits than are possible in a day. We know the path forward to expanding telehealth relies on CMS addressing the potential for fraud and abuse in telehealth, as we do with all services [6].

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2020) Publication manual of the American Psychiatric Association (6th edn), American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, USA.

- Javed A, Mohandas E, De Sousa A (2020) The interface of psychiatry and COVID-19: Challenges for management of psychiatric patients. Pak J Med Sci 36(5): 1133-1136.

- Kannarkat JT, Smith NN, McLeod Bryant SA (2020) Mobilization of telepsychiatry in response to COVID-19-moving toward 21st Century Access to Care. Adm Policy Ment Health 47(4): 489-491.

- Myers KM, Valentine JM, Melzer SM (2008) Child and adolescent telepsychiatry: utilization and satisfaction. Telemed J E Health 14(2): 131-137.

- Shore JH, Schneck CD, Mishkind MC (2020) Telepsychiatry and the corona virus disease 2019

Pandemic-Current and Future Outcomes of the Rapid Virtualization of Psychiatric Care. JAMA Psychiatry. - Seema V (2020) Early impact of CMS expansion of Medicare Telehealth during COVID-19.

© 2020 Shamil Ul Haque Abbasy M, This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)