- Submissions

Full Text

Psychology and Psychotherapy: Research Studys

A Pilot Study on Functional Analytic Psychotherapy Group Treatment for Borderline Personality Disorder

Michel A Reyes Ortega1*, Angélica Nathalia Vargas Salinas1 and Jonathan W Kanter2

1 Contextual Behavioural Science and Therapy Institute, USA

2 University of Washington, USA

*Corresponding author: Michel A Reyes Ortega, Contextual Behavioural Science and Therapy Institute, México City, USA

Submission: April 05, 2018;Published: October 31, 2018

ISSN 2639-0612Volume1 Issue5

Abstract

A randomized clinical trial (RCT) was conducted to test the impact of Functional Analytic Psychotherapy (FAP) on individuals diagnosed with borderline personality disorder (BPD) who had finished treatment as usual (TAU) at a public institution in Mexico City. Two groups receiving 8 sessions of FAP (n=26) or Interpersonal Skills training (n=24) where compared. T-test analyses found statistically significant (p< 0.05) and large (Cohen’s d≥0.80) improvements for FAP group participants at post-test compared to pre-test in BPD symptom severity, intimacy, experience of self and emotion regulation. Between groups analysis found statistically significant and large effects in favor of FAP, with the largest differences observed in intimacy. Regression analysis found a reduction in the relation between intimacy and BPD severity before (R2=0.324) and after FAP treatment (R2=0.11). These results suggest FAP’s possible utility as an adjunct treatment for BPD.

Keywords:RCT: Randomized Clinical Trial; BPD: Borderline Personality Disorder; FAP: Functional Analytic Psychotherapy; TAU: Treatment as Usual; FIV: Inflated Variance Factor

Introduction

From a contextual behavioural standpoint, personality traditionally has been understood as an organized behavioural repertoire controlled by contingencies [1]; more recent approaches have described personality traits as functional classes of behaviour that differ in variety, flexibility and generality across individuals [2,3]. This perspective differs from the structuralist view in which personality is understood as a “psychological structure” that manifests in the person’s behaviour [4,5] presented a contextual behavioural model of borderline personality disorder (BPD) that integrated previous models [6] with behaviour analytic understandings of the development of self, personality, and experiential avoidance. The Reyes et al. model views the major behavioural problems of BPD as a severe experiential avoidance pattern shaped by the interaction of innate difficulties in self-regulation and an invalidating environment. Briefly, his model states that the interaction between difficulties in emotion regulation and a history of abuse or neglect result in extreme conditioned emotional responses and paranoid states that are elicited by similar events in the adult life. The model establishes a relation between the onset of the abuse and the severity of symptoms; young children may lack emotion regulation skills and react to escape urges with experiential avoidance actions that interfere with psychological habituation, emotional processing and problem solving, inadvertently leading to increased symptoms and dissociative states [7,8]. The model also relates chronically invalidating environments, which include abuse and neglect, with the dif ferential reinforcement of “I” responses under public control which in turn produces a poor or unstable sense of self [9] dysfunctional self-regulation skills including suicidal and parasuicidal behaviour [10] and a disorganized-ambivalent attachment style leading to instability in interpersonal relationships [11]. These behaviours are under aversive control and therefore frequently evoked by aversive conditions (sickness, working stress, marital conflict, etc.). The behaviours are negatively reinforced in the short term, but inconsistent with personal values and goals in the long term, creating more pain and a growing sense of chaos and emptiness.

While different psychotherapeutic models have shown to be useful for reducing suicidal and self-harming behaviour, depression and anxiety and severity of BPD symptoms, and improving emotion regulation [12-18], social connection related symptoms are still a challenge for clients and therapist. We believe functional analytic psychotherapy (FAP) could be a useful supplement for BPD existing treatments.

Functional analytic psychotherapy (FAP), an approach rooted in contextual behavioural science that focuses on the therapeutic relationship as the agent of change, and particularly promising to improve people’s relationships. FAP distinguish itself from other CBS approaches in respect to the amount of time and attention given to building a strong and genuine human relationship that promotes learning and change. FAP promotes increased awareness of both the client and the therapist, been courageous to take interpersonal risks by experiencing and disclosing emotional reactions as they occur in-session and, the provision of genuine feedback to increase the connection through this exchange. This vulnerability and immediacy serve as a model to help the client improve connections with others, which is an important transdiagnostic outcome [19].

FAP leverages five rules, to conceptualize client behaviours occurring in session (clinically relevant behaviours or CRBs), evaluate their functions, and conditionally change problematic behaviours (CRB1s) or reinforce desirable behaviours (CRB2s) through the interpersonal dynamics occurring in the dyadic relationship [20,21]. Recent FAP writings have discussed how the implementation of FAP’s five behavioural rules may be supplemented with an understanding of awareness, courage, and therapeutic love towards clients, repertoires which could also be defined as CRB2s for clients suffering from lack of intimacy in their daily lives. We believe FAP or FAP based interventions could be add in evidence based behavioural treatments for BPD, which had proved to be effective for the improvement of emotion regulation, reduction of self-harm behaviours, and reduction of depression and anxiety, but still in need of improvement in life satisfaction domains, such as social connection.

Method

Participants

49 BPD diagnosed clients of a mental health care clinic of the state of Mexico, 4 males and 45 females, ages ranged from 19 to 40 years old participated in this study. Only clients with life quality problems and no life and therapy interfering behaviors or PTSD were considered to participate in the study. At the beginning of the study, participants had passed a minimum of 4 months without self-harm or suicidal behavior, had completed between 24 and 48 sessions of psychotherapy attending at a regular basis, showed adequately compliance with pharmacotherapy, didn’t showed impairment for global adaptation in the last month, and didn’t showed problems of social adjustment related to affective symptoms severity.

Clients were invited to take part of the study by their psychotherapist, who explained the study had the aim to assess the impact of an intervention for social connection and assessed wetter the clients considered to have intimacy related problems. Participants who considered having intimacy related problems were included in the study, exclusion criteria included participants showing suicidal ideation or self-harm at some point of the study.

5 therapists participated in the study. FAP for BPD ACL-Skills training was conducted by one certified FAP therapist (male, 33 years old) who function as group leader and two co-therapists (female, 30 years old; male 43 years old), Co-therapists’ functions where to provide crisis intervention if needed, participate as models before evocative exercises, and sharing experiences during discussions. The social skills training was administered by one group leader (male, 34 years old) and two co-therapists (female, 28 years; male, 32 years). Both clinical teams where assisted by a monitor in charge of logistic duties like taking participants attendance or giving them session handouts, this was 4th year psychiatry resident (female, 28 years).

FAP ACL skills training groups for people with BPD

The FAP ACL skills training group was a group format treatment consisting of 8 weekly sessions of two hours length. Range of participants per group is of 15-20 clients and 3 therapists, one of the therapists playing the role of group leader at a time. This groups where design to enhance ACL skills (CRB2s) evoked within the therapy session through the participation of evoking exercises, the development of a functional self-understanding of behavior (CRB3- 2) and the generalization of desirable behaviors (ACL behaviors) in the natural environment (O2). These variables are not directly assessed in this study, instead, general BPD treatment targets where measured to assess treatment impact.

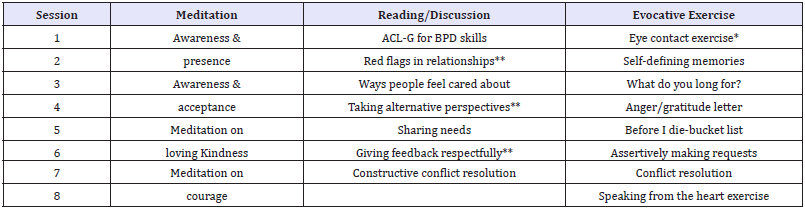

Session structure is the same in each meeting. It starts with a FAP meditation exercise followed by each participants and therapists sharing of their experience during the exercise, this experience is then summarized a blackboard. Next, except for the first session, the Emotional Risk log is reviewed. After this a group lecture about a FAP relevant topic is made and a related evocative exercise is modeled by therapist and then practiced in pairs by clients, in the first exercise one member shares courageously and the other listens with awareness to then provide loving feedback, this is naturally reinforcing the sharer courage trough self-disclosure of feelings to provide company in the emotional experience, highlighting similitudes between them to validate or validating directly how the experience of the partner make sense, at the end, the sharer tells the listener about what she found to be more effective in their feedback, this is considered to be a love action driven by awareness of the courage it takes to give loving feedback. After this exchange, participants shift roles, finally the dyads experience is reviewed. At the end of the session, a Risk log is given to the participants who practice being aware of themselves and engage in courageous interpersonal actions and self-love attitude across the week. This risk log is reviewed at the beginning of each session. Table 1 describe each session activities.

Table 1:ACL-G for BPD description.

Note: *This exercise was taken from Hayes, Strosahl & Wilson 1999

**This reflection is taken from Morton & Shaw 2012

The rest of the exercises are adapted from the original Interpersonal Connections Study

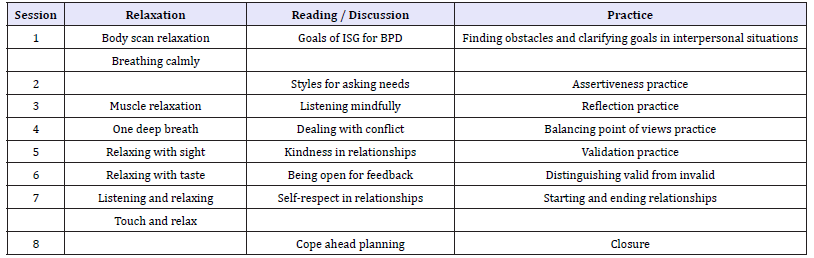

Table 2:IS-G for BPD description.

Note: This protocol was adapted from DBT Skills Training Manual second edition [6].

The objective of the present study was to assess the impacts of the FAP ACL-Skill training groups in a sample of BPD diagnosed group of clients who had received 24 to 48 sessions of treatment as usual (TAU) in comparison to a group of the same characteristics that received a social skills training intervention (Table 2). It was hypothesised that the group receiving FAP ACL-Skills training would show better outcomes in the assessed variables. To prove this hypothesis, participants were assigned randomly to any of the groups and assessed before and after experimental treatments and after 6 months as follow up.

Measures

Intimacy - FAP Intimacy Scale [22]. This is a 14-item selfadministered measure developed to assess intimacy-related behavior. It consists of three factors that are answered according to the responder relationship with a chosen other: a) Hidden Thoughts and Feelings (α=0.93), with items like “When I talked to this person, I stuck to safe topics.”; b) Expression of Positive Feelings (α=0.92), consisting of questions like “I attempted to get closer to this person”; and Honesty and Genuineness (α=0.91) which includes items like “I showed my true feelings and behaved completely naturally with this person”. The scale showed good internal consistency (α=0.86), test–retest reliability (r=0.73) and construct validity. An unpublished Mexican version of this scale was used for this study (α=0.84), a pilot study was conducted to assess its psychometric properties, preliminary analysis of this measure where conducted with 100 postgraduate students in clinical psychology, the tree factors model of the original scale where maintained (α=0.88, α=0.86 and α=0.90 respectively), test retest reliability was assessed with only 36 students (r=0.75).

BPD symptoms severity - Borderline Evaluation of Severity Over Time Scale [23]. The scale includes 15 items and three subscales. All items are rated on a Likert-like scale. The first eight items comprise subscale A (Thoughts and Feelings), and involve assessments of mood reactivity, identity disturbance, unstable relationships, paranoia, emptiness, and suicidal thinking; an example of an item included is “Worrying that someone important in your life is tired of you or is planning to leave you”. The next four items comprise subscale B (Behaviours-Negative), which rates negative actions such as injuring oneself, Items on these subscales are rated from 1 (None/Slight) to 5 (Extreme), this subscale includes items such as “Purposefully doing something to injure yourself or making a suicide attempt”. The final three items comprise subscale C (Behaviours- Positive), which rates actions such as following through on therapy plans. These items are rated from 5 (Almost Always) to 1 (Almost Never) and includes items as “Choosing to use a positive activity in circumstances where you felt tempted to do something destructive or self-defeating”. To score the BEST, the total for each subscale is determined. The scores of subscales A and B are then added together and the total from subscale C is subtracted. A correction factor of 15 is added to yield the final score which can range from 12 (best) to 72 (worst). The BEST was designed to measure severity in an ill population and was not designed as a diagnostic instrument. Cronbach’s α coefficients at baseline for subjects with BPD were 0.86. Test Retest reliability was moderate (r=0.62, n=130, P< 0.001). The scale also demonstrates excellent discriminant validity and is sensitive to clinical change occurring as early as week 4 of the study. The unpublished Mexican version of the scale show α coefficients of 0.88 for subjects diagnosed with BPD.

Emotion Dysregulation - Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale [24,25]. The Mexican version of this scale is a self-report questionnaire of 24 items (α=0.93) consisting of four factors: a) Nonacceptance of emotional responses, containing items like “I am clear about my feelings”; b) difficulties in engaging in goal-directed actions, consisting of questions like “when I’m upset, I have difficulty focusing on other things”; c) Lack of emotional awareness, with reverse scored items like “I care about how I’m feeling”; and d) Limited access to emotion regulation strategies, with items like “when I’m upset, I believe that I’ll end up feeling very depressed”. Each subscale alpha ranged from 0.85 to 0.68. Between group validity and concurrent measure correlations where significant (r=0.51 to 0.76, p< 0.05). The questionnaire was answered by each participant individually prior to the first and after the final treatment session.

Experience of Self - Experience of Self Scale [26-28]. The Spanish version of EOSS is a measure with high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.941) and significantly high correlations with the EPQ-R Neuroticism scale and the DES Dissociation scale, while showing negative correlations with the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES). It consists of 4 principal factors: a self in close relationships (α=0.594) characterized by items as “I am at a loss when people say to me “be yourself”; a self with casual social relationships (α=0.935) with items like “My attitudes are influenced by them when I am with them”; a self in general (α=0.951) with items like “My “wants”* are influenced by them when I am with them. (*by wants we mean what you want to do, want to have, etc.)”; and a positive self-concept (α=0.720) that includes items like “I am creative when I am alone”. Significant statistical differences were found between the clinical and standard sample, the former showing a higher average.

Procedure

All clients where recommended to receive treatment after suggestion of other health clinics. BPD diagnosed was assigned by a licensed psychiatric and confirmed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Axis II Disorders [29] and the Million Clinical Multiaxial Inventory [30], comorbid disorders ranged from depression to anxiety spectrum. After receiving diagnosis, clients received pharmacological treatment at psychiatrist discretion and weekly sessions of psychotherapy with a behavioral orientation. Clients who completed 24 to 48 sessions of psychotherapy where assigned randomly to either one of the groups, FAP ACL-G or IS-G training. Measures were administered in a group format by the groups monitor before the first FAP ACL-Skills training or Social skills training sessions accordingly, and after the last session. Treatment integrity was assessed by the adherence to treatment manual and the presence of certified therapists in both groups. Clients continued receiving treatment after the study and where asked directly or by phone after 6 months of the posttest to receive a follow up treatment session and answer the measures again. It was impossible to gather a group after 9 months, participants reported impossibilities of assistance, and job or school reinsertion. Data was collected by a research assistance external to the group who participated in the study. Data was analyzed using statistical program SPSS.

Results

Descriptive statistsics

Table 3:Study participants’ characteristics.

At the end of the study, 50 BPD diagnosed clients, 4 males and 46 females, ages ranged from 19 to 40 years old finished the study. Clients characteristics are described in Table 3.

Inferential statistics

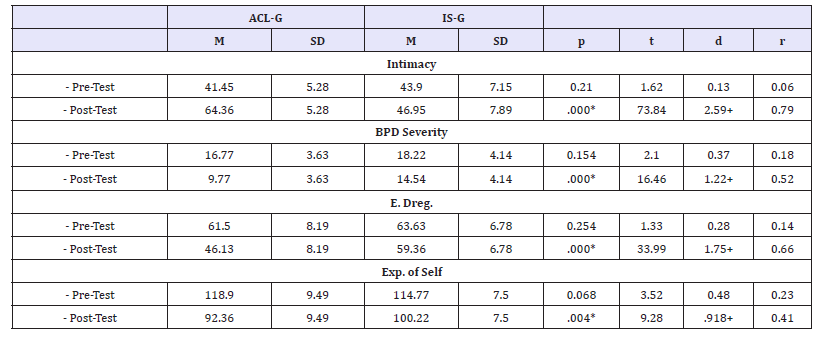

Levine test showed groups where equivalent at pretest on intimacy (F=0.238, p=0.628), bpd symptom severity (F=0.313, p=0.579), emotion dysregulation (F=0.237, p=0.629), and experience of self (F=2.77, p=0.103). Therefore, we proceeded to do an ANOVA with 99% of confidence interval to identify within and across groups differences. T-test analysis found statistically significant (p≤0.05) and large size effects (d≥0.80) improvements in FAP group. Table 4 shows differences between ACL-G ad IS-G group scores at post-test.

Table 4:Statistical differences and size effects between ACL-G and IS-G scores (Pre-Post Test scores).

Measures: Intimacy=FAPIS; BPD symptoms severity=BEST-E (last month scores); Emotion Dysregulation (E. Dreg.) =DERS-E; Self Under Public Control (Exp. of Self) =Experience of Self Scale Note: *=Statistically significant differences p ≤0.05; +=Large Size effect d ≥0.80

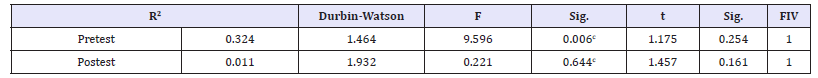

Table 5:Linear Regression model FAP group before and after the intervention to explain the severity of symptoms in borderline personality disorder.

N=22 BPD Symptom Severity Scale (BEST) and Intimacy Scale (FAPIS) Predictor variables: (Constant), Intimacy Privacy Dependent variable: BEST Postest

We tried to determine if the intimacy mediated the BPD symptoms in the FAP group. The procedure was a linear regression in two moments, the first before the intervention, where the intimacy variable explained 32.4% of the variance of BPD symptoms scores obtained on the BPD symptom severity Scale (BEST) and intimacy scales (R2=0. 324) and where the Durbin Watson test indicates that the assumption of error independence (1,464) is met, as well Than the inflated variance factor (FIV). The same procedure was performed with the measurements obtained after the application of FAP treatment, where R2 decreased (R2=0.11), which indicates that the percentage of variance explained in the severity of symptoms decreased, as did the Severity of symptoms and is related to the increase in intimacy scores is seen in Table 5.

Discussion

We believe this study suggest tree theoretical questions to future research on behavioural treatments for BPD. First, ACL-G group outperformed IS-G in all the assessed variables and showed a slightly better adherence, which lead to the acceptance of the research hypothesis. More significantly, intimacy seems to be affected by FAP, but no by Interpersonal Skills, adding evidence to the FAP theory that intimacy is a process that requires the vulnerable expression of feelings and expressions of care to develop, process that doesn´t seem to be affected by standard interpersonal or social skills trainings.

Second, we think that emotion dysregulation and BPD symptoms severity reductions in FAP group could be a function of the same process, and the in vivo exposure quality nature of the evocative exercises of the ACL-G. In other words, the awareness of the present moment in highly emotional situations along with the practice of courageous and loving responses could be representative of the hypothesized process needed for emotion regulation such as being able to recognize emotion without avoiding or suppressing it and finding a more important goal and organizing action according to it [31]. Emotion regulation mediated BPD symptom severity in FAP group.

Finally, according to FAP theory of the development of Self as a functional class Kohlenberg & Tsai 1991, experience of self under private control mediated emotion regulation in FAP, this could indicate that the intimate interactions created in the ACL-G functioned to Evoque I tact’s under private control, a selfdiscrimination needed for emotion regulation and usually lacking in BPD diagnosed individuals. Future FAP processes research could help in asking this question.

Clinical impacts of this pilot study need to be replicated in a study with follow ups to asses outcomes sustainability. Replications should be implemented by students with a brief prior training to evaluate the cost effectiveness of this intervention. Finally, replications in similar institutions are needed to asses and contribute to the development of EST in low resource situations. Efficacy designs that compare the whole model of treatment (TAU+FAP) in comparison with other Mexican institutions treatment for this condition could provide answer to this treatment effectiveness and feasibility of dissemination in similar institutions.

This study suggest FAP could be a valuable addition to other behavioural interventions for severe behavioural disorders with strong interpersonal difficulties, we believe that FAP constitute a good base to the development of treatment protocols that target interpersonal problems like intimacy, connection, perceived loneliness, or empathy as dependant variables. Whether FAP could work as a standalone treatment for this kind of behavioural problems is unknown.

References

- Skinner BF (1974) About behaviourism. Knopf, New York, USA.

- Gaynor ST, Baird SC (2007) Personality disorders. In: Woods DW, Kanter JW (2007) (Eds.), Understanding Behaviour Disorders: A Contemporary Behavioural Perspective. New Harbinger, Oakland, CA, USA, pp. 287-330.

- Luciano MC, Gómez Becerra I, Valdivia Salas S (2002) C2onsideraciones acerca del desarrollo de la personalidad desde un marco funcionalcontextual. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy (2)2: 173-197.

- Sturmey P (2008) Behavioural case formulation and intervention: A functional analytic approach. Wiley, New York, USA.

- Reyes MA, Vargas AN, Tena A (2015) Hacia un modelo teórico del trastorno límite de la personalidad. Psicología Iberoamericana 23(2): 7-18.

- Linehan MM (1993) Cognitive behavioural treatment of borderline personality disorder. Guilford Press, New York, USA.

- Briere J (1992) Child abuse and trauma. Sage Publications, New York, USA.

- Morton J, Buckingham B (1994) Service options for clients with severe or borderline personality disorders: consultant’s report. Melbourne, Vic. Department of Health and Community Services, Psychiatric Services Branch Victoria.

- Kohlenberg RJ, Tsai M, Kanter JW, Parker ChR (2009) Self and mindfulness. In: Tsai M, Kohlenberg RJ, Kanter JW, Kohlenberg B, Follete WC, et al. (Eds.), A guide to functional analytic psychotherapy; Awareness, couragel love, and behaviourism, Springer, New York, USA, pp. 131-144.

- Linehan MM, Heard HL, Armstrong HE (1993) Naturalistic follow-up of a behavioural treatment for chronically parasuicidal borderline clients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 50: 971-974.

- Mansfield AK, Córdova, JV (2007) A contemporary behavioural perspective on adult intimacy disorders. In: Woods D, Kanter J (Eds.), Understanding behaviour disorders: A contemporary behavioural perspective. Context Press, Reno, NV, USA.

- Gratz KL, Gunderson JG (2006) Preliminary data on an acceptance-based emotion regulation group intervention for deliberate self-harm among women with borderline personality disorder. Behav Ther 37: 25-35.

- Koons CR, Robins CJ, Tweed JL, Lynch TR, Gonzalez AM, et al. (2001) Efficacy of dialectical behaviour therapy in women veterans with borderline personality disorder. Behaviour Therapy 32: 371-390.

- Linehan MM, Kanter JW, Comtois KA (1999) Dialectical behaviour therapy for borderline personality disorder: efficacy, specificity, and cost-effectiveness. In: Janowsky DS (Ed.), Psychotherapy: Indications and outcomes. American Psychiatric Press, Washington, DC, USA, pp. 93-118.

- Morton J, Snowdon S, Gopold M, Guymer E (2010) Acceptance and commitment therapy group treatment for symptoms of borderline personality disorder: A public sector private study. Cognitivo and Behavioral Practice 19(4): 527-544.

- Verheul R, Van den Bosch LMC, Koeter MWJ, de Ridder MAJ, Stijnen T, et al. (2003) Dialectical behaviour therapy for women with borderline personality disorder: 12-Month, Randomised Clinical Trial in the Netherlands. Br J Psychiatry 182: 135-140.

- Van den Bosch LMC, Maarten WJ, Koeter MWJ, Stijen T, Verjeul V, et al. (2005) Sustained efficacy of dialectical behaviour therapy for borderline personality disorder. Behav Res Ther 43: 1231-1241.

- Linehan MM, Dimeff LA, Reynolds SK, Comtois K, Shaw Welch S, et al. (2002) Dialectical behaviour therapy versus comprehensive validation plus 12-Step for the treatment of opioid dependent women meeting criteria for borderline personality disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 67: 13-26

- Wetterneck ChT, Hart JM (2012) Intimacy is a transdiagnostic problem for cognitive behaviour therapy: functional analytical psychotherapy is a solution. The International Journal of Behavioural Consultation and Therapy 7: 167-176.

- Tsai M, Callaghan G, Kohlenberg RJ (2013) The use of awareness, courage, therapeutic love and behavioural interpretation in Functional Analytic Psychotherapy. Psychotherapy 50(3): 366-370.

- Tsai M, McKelvie M, Kohlenberg R, Kanter J (2014) Functional analytic psychotherapy: Using awareness, courage and love in treatment. Society for the Advancement of Psychotherapy.

- Leonard R, Knottm LE, Lee EB, Singh S, Smith AH, et al. (2014) The development of the functional analytic psychotherapy intimacy scale. Psychological Record (64): 647-657.

- Pfohl B, Blum N, John DS, McCormick B, Allen J, et al. (2009) Reliability and validity of the Borderline Evaluation of Severity Over Time (BEST): a self-rated scale to measure severity and change in persons with borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord 23(3): 281-293.

- Gratz KL, Roemer L (2004) Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioural Assessment 36: 41-54.

- Marín Tejeda M, Robles García R, González Forteza C, Andrade Palos P (2012) Propiedades psicométricas de la escala “Dificultades en la Regulación Emocional” en español (DERS-E) para adolescentes mexicanos. Salud mental 35: 521-526.

- Kanter JW, Parker CR, Kohlenberg RJ (2001) Finding the self: A behavioural measure and its clinical implications. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training 38(2): 198-211.

- Patrón F (2010) La Evitación Experiencial y su medición por medio del AAQ-II. Enseñanza e Investigación en Psicología 15: 5-19.

- Valero Aguayo L, Ferro García R, López Bermúdez MA, Selva López de Huralde M (2014) Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Experiencing of Self Scale (EOSS) for assessment in Functional Analytic Psychotherapy. Psicothema (3): 415-422.

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW (1995) The structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R personality disorders (SCID-II), I: Description. Journal of Personality Disorders 9: 83-91.

- Millon T, Millon C, Davis R, Grossman S (1994) MCMI-III. Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory-III. Manual (4th edn), San Antonio, Pearson Clinical, Texas, USA.

- Werner K, Gross JJ (2010) Emotion regulation and psychopathology: A conceptual framework. In: Kring AM, Sloan DM (Eds.), Emotion regulation and psychopathology: A transdiagnostic approach to ethology and treatment. Guilford Press, New York, USA, pp. 13-37.

© 2018 Michel A Reyes Ortega. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)