- Submissions

Full Text

Psychology and Psychotherapy: Research Study

How Well Do You Know Your Best Friend?

Samantha Smith*, Kyle Lange, Simi Prasad and Justin Jungé

Department of Psychology, Princeton University, USA

*Corresponding author: Samantha Smith, Department of Psychology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08540, USA

Submission: January 01, 2018;Published: February 16, 2018

ISSN 2639-0612Volume1 Issue1

Abstract

Previous research supports that romantic partners view one another’s attributes more favorably than their partners self-reported attributes. Furthermore, research has shown that relationship satisfaction and self-esteem have been positively associated with idealistic perceptions of one’s romantic partner. Yet, it is not clear if trends of idealization exist amongst close friends and how such trends might correlate with measures of selfesteem and friendship satisfaction. The purpose of this paper is to analyze perceptual differences amongst pairs of friends across an array of positive and negative interpersonal attributes. To provide baselines for assessing friendship idealization, male and female undergraduate students at Princeton University were asked to rate themselves, a close friend, and their ideal friend across a variety of characteristics. Participants were also asked to indicate measures of friendship satisfaction, self-esteem, and closeness. Analyses revealed that friends viewed one another more positively than they viewed themselves. Furthermore, individuals’ impressions of their friends were more a mirror of their ideals than a reflection of their friends’ self-reported attributes; however, no correlation was found between levels of idealization and reported measures of friendship satisfaction, self-esteem, or closeness. Gender differences were minimal, excluding perceived measures of friendship closeness; women viewed their friendships as closer than men did. These results suggest that individuals idealize their close friends’ interpersonal attributes, although the motivation to do so cannot be generalized.

Keywords: Idealistic versus realistic perceptions of friend; Friendship satisfaction; Self-esteem; Friendship intimacy

Introduction

Friends are some of our closest connections. In studies conducted by Sapadin LA [1] and Prager KJ [2] both men and women listed intimacy as the most common characteristic of close friendships. These results were substantiated in a study conducted by Berscheid E [3], Snyder M & Omoto AM [4] in which 250 undergraduate students were asked to name their deepest, closest, most intimate relationship: 14% named a family member, 47% named a romantic partner, and 36% named a friend. “Friendship is the hardest thing in the world to explain. It’s not something you learn in school. But if you haven’t learned the meaning of friendship, you really haven’t learned anything.” ― Muhammad Ali

As Ali stated, friendships are quite difficult to explain, and this is especially true from a scientific perspective. Despite friendships being some of our most intimate relationships, not much is known about the value of particular interpersonal attributes in close friends, especially in comparison to qualities that are valued in romantic partners [5]. Evolutionarily, interpersonal attributes akin to support and sensitivity can be generalized as ideal in most romantic partners because these qualities affect one’s emotional well-being, and romantic partners are expected to be one’s closest emotional connection [6].

In contrast, it has been proposed that the role of friends evolved because others often possess qualities, abilities or tools that compliment one’s own, leading to better outcomes for both individuals [7]. Thus, generalizing what individual value in a best friend proves difficult because ideal interpersonal attributes vary from person to person [8]. In this sense, one’s friends may be judged by their unique fit to you, rather than a general set of desirable qualities [7,9,10].

A study conducted by Murray SL, Holmes JG & Griffin DW [11] found that when asked to evaluate the interpersonal attributes of oneself and one’s romantic partner, romantic partners rated one another more favourably than they rated themselves. This study also observed that greater levels of idealization correlated with greater levels of relationship satisfaction and self-esteem. The purpose of the present study is to expand on these results, noting if such trends apply to platonic friendships. Additionally, we note whether or not increased measures of closeness correlate with higher levels of idealization in friendships.

In summary, this paper examines the following four questions:

a) Do people view their friends more positively than their friends view themselves?

b) How do people view their friends in relation to themselves and in relation to their ideal friends?

c) Do men and women have different perceptions of an ideal friend?

d) How do self-esteem, friendship satisfaction, and friendship closeness impact these results?

Positive Perceptions and Idealization in Friendships

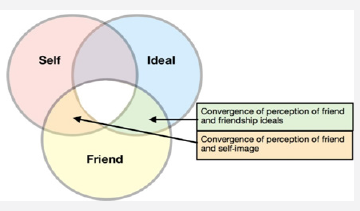

By using friends’ self-impressions as “reality” baselines, this study will investigate whether friends project their self-images and ideals onto one another, thus seeing one another differently, even more positively, than their friends see themselves [11]. Individuals’ perceptions of their friends’ attributes should mirror their friends’ self-perceptions to the extent that they both reflect a shared social reality, for which this study has accounted. Indeed, considerable evidence suggests that social perceivers often agree on one another’s attributes [12-14]. We hope to show that friends’ impressions of one another are as much a mirror of their own self-images and ideals as they are a reflection of their actual, or at least self-perceived, attributes. If idiosyncratic construal indeed plays a preeminent role in shaping friends’ images of one another, we expect such realities may diverge and individuals may perceive their friends distinctly from how their friends see themselves. Such convergences of perception are reflected in the green and orange shaded areas of (Figure 1) [11].

Figure 1: Projection of friendship ideals vs self-image onto friends. Adapted from Murray, S.L., Holmes, J. G., & Griffin, D. W., 1996.

Men and Women’s Perceptions of an Ideal Friend

We questioned whether men and women’s views of an ideal friend would differ. Various studies have shown that men and women approach intimacy in close friendships differently [8,15- 18]. Studies have also shown that ideal friendship attributes vary by the individual [7,10,19]. We were particularly curious to see if the data showed gendered differences in an ideal friend, or if ideals would be unique to individuals.

Friendship Satisfaction, Self-Esteem, and Closeness

There are many hypotheses for why individuals idealize their romantic partners. Freud S [20] proposed that romantic partners project the qualities they wish to see in themselves onto one another and Bowlby J [21] argued that partners idealize one another’s attributes because doing such increases long term feelings of security. Murray SL, Holmes JG & Griffin DW [22] noted that higher measures of relationship satisfaction correlated with greater idealization levels, and they believed this was due to romantic partners’ shared illusions of one another. We tested to see if measures of idealization could similarly predict measures of friendship satisfaction.

Bowlby J [23] and other attachment theorists have argued that one’s self-image and image of other are deeply intertwined, thus implying that individuals’ idiosyncratic perceptions of an ideal partner are conditional on self-esteem. Murray SL, Holmes JG & Griffin DW [22] found that higher levels of self-esteem correlated with greater levels of idealization, seemingly corroborating arguments by attachment theorists [8,23-25]. To further explore the self-verification hypothesis in close friendships, we examined the correlations between participants’ levels of idealization and their scores on an adapted version of the Rosenberg’s self-esteem scale Rosenberg M [26] as was done in the study conducted by Murray SL, Holmes JG & Griffin DW [22].

Lastly, we chose to include a measure of closeness because intimacy has been named a key characteristic of close friendships by both men and women [4,27]. We were particularly interested in noting differences in perceived closeness across genders, as there has been much debate surrounding whether or not women’s friendships are closer than men’s [18,28-34].

Hypotheses and Alternative Outcomes

We hypothesized that individuals would view their friends more positively than their friends viewed themselves, seeing their negative qualities as less negative and their positive attributes as more positive. Furthermore, we hypothesized that certain trends of idealization of one’s romantic partner may also be applicable to one’s best friends since both relationships are quite intimate; we expected individuals to view their friends as closer to their unique ideals than to their friend self-reported attributes. In regards to gender differences, we hypothesized that individuals may idealize their close friends in unique ways because there is less pressure to choose a friend who fits a set social standard; furthermore, we believed ideals would be dependent on individual differences, rather than gendered preferences. Lastly, we were curious as to how self-esteem, closeness, and friendships satisfaction would correlate, if at all, to levels of idealization. We did not hypothesize how these trends would play out.

Materials and Methods

94 undergraduate students (33 males and 61 females; 18 to 22 years of age), including 37 pairs of friends, participated in the present study at Princeton University in Princeton, NJ. For the sake of clarity, the recruited participants will henceforth be called “Participants” and their successfully recruited friends will be called “Friends”. This will mostly serve for clarity when discussing question 1, in which 37 pairs of friends were studied. Informed consent was obtained from all participants via Qualtrics through a web-based survey. (See Appendix A) The data for this paper were generated using Qualtrics software, Version 12/2017 of Qualtrics. © 2017 Qualtrics.

Initial recruitment emails were sent to undergraduate students at Princeton University who are friends of the researchers and to student residential college e-mail listservs. Final recruitment emails were sent to 350 random undergraduate students by The Survey Research Center at Princeton University. Participants and Friends were recruited in pairs. When completing the survey, each Participant was asked to identify one Friend about whom they would respond. Criterion for selecting a friend were as follows: a current Princeton undergraduate student, not a family member, not a significant other, someone you consider a close/best friend. A second recruitment email was then sent to each Friend, asking them to take the same survey about the corresponding Participant. The 20 cases in which a complete pair did not fill out the survey were disregarded when analyzing question 1, but these data were included when answering questions 2, 3, and 4. On average, the survey took 5-10 minutes to complete. Participants received neither monetary compensation nor course credit for participating in this study.

The distributed survey included

a. a consent form;

b. a demographic questionnaire;

c. a question concerning whether or not a participant had selected them to complete the survey;

d. measures of closeness;

e. a randomized list of interpersonal attributes that were scaled to measure participants’ views of “You”, “Your Friend”, and “Your Ideal Friend”;

f. a measure of self-esteem;

g. a measure of friendship satisfaction.

The first page of each survey asked respondents for the following demographic information: name, class year, age, gender. We took note of gender to complete comparative analyses amongst men and women. Names were solely used to pair Participants and Friends when analyzing question 1. Class year and age were obtained in the hopes of making comparisons with length of friendships and age differences, but the small disparity in ages and class years led this to not be a focus of this study.

At the bottom of the first page, participants were asked if they were selected to complete the survey by a friend (other than the researchers). If they selected “no”, Participants were then asked to identify one Friend about whom they would respond; if they selected “yes”, Friends would automatically skip to the next set of questions about closeness. Participants and Friends indicated responses to four measures of closeness: hours spent together per week (0 to 4, 4 to 8, ------20+), activities done together (eating, extracurricular, social), how well they know the other person, and how well the other person knows them. The latter two items were measured on an 11-point scale (0 = Barely; 10= Extremely well).

Murray SL, Holmes JG & Griffin DW [22] included a 21-item measure of interpersonal attributes, both positive and negative, that were selected from the interpersonal circle Leary T [35], Wiggins JS [36] when studying idealization in romantic relationships. We deemed these terms better suited for couples than platonic friends, as they dealt with more intimate dimensions of warmth-hostility and dominance-submissiveness that characterize romantic relationships [37]. Instead, we developed a 20-item measure of interpersonal attributes based on their relevance to the social exchange process [38]. We chose 10 negative and 10 positive attributes: ignorant, impatient, quarrelsome, rude, thoughtless, cowardly, incompetent, cold, dishonest, boring, confident, attentive, witty, agreeable, passionate, supportive, sociable, compassionate, trustworthy and intelligent.

We then asked participants to rank how characteristic these attributes were of their friend, themselves, and an ideal friend. In defining an “ideal friend,” we attempted to ensure that participants described their own idiosyncratic wants in an ideal friend, rather than a presupposed cultural standard; hence, we asked participants to rank attributes for an ideal friend tailored to their desires. Participants and Friends rated how well each of the traits described “You”, “Your Friend”, and “Your Ideal Friend” on a 7-point Liker scale (-3 = extremely uncharacteristic; 3 = extremely characteristic). To reduce bias, the 20 interpersonal attributes were presented in a random order. Further, the blocks for “You”, “Your Ideal Friend”, and “Your Friend” were randomized. (See Appendix A)

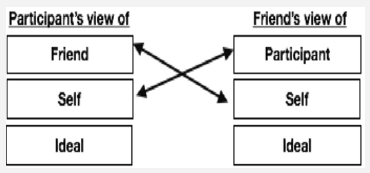

Figure 2: Constructing impressions: set-up for the projection of ideals vs self-image onto friends.

To address question [39] do people view their friends more positively than their friends views themselves? The difference in the responses of the 37 pairs of Participants and Friends were analyzed. (Figure 2) shows the comparison measure used to find each difference. Participants’ and Friend’s views of one another were compared to their self-reported attributes. A positive difference always translated as the Participant’s viewing the Friend (or the Friend’s viewing the Participant) more positively than they viewed themselves. Adopted from Murray SL, Holmes JG & Griffin DW [22].

To address question [40] How do people view their friends in relation to themselves and in relation to their ideal friends?, the absolute difference between each participant’s view of their friend and themselves, as well as the absolute difference between each participant’s view of their friend and an ideal friend, were calculated. These measures indicate whether participants’ views of their friends are more a projection of themselves or of their ideal friend [22,40]. In calculating the absolute value of these differences, a smaller difference correlates with a larger overlap in Figure 1; likewise, a larger overlap between the “Self” and “Friend” circles compared to the “Ideal” and “Friend” circles indicates that one has a tendency to view their friend more like they view themselves [16,41] (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Average difference between participant view of friend and friend view of self.

To address questions [42] Do men and women have different perceptions of an ideal friend? and [43] How do self-esteem, friendship satisfaction, and closeness relate to differences inperception or idealization of one’s friends?, male and female participants’ responses of desired interpersonal attributes of an ideal friend were compared. Measures of friendship satisfaction, self-esteem and closeness were also used to draw correlations across the target four questions.

Self-esteem was measured on a 4-point scale (0 = strongly disagree; 4 = strongly agree) and was an average of participants’ responses to three self-esteem questions taken from the Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale [26]. Only three of the ten questions were used for the sake of brevity, and previous research has indicated that a single question is a reliable measure of self-esteem [46]. The friendship satisfaction score was measured out of 9 and was an average of participants’ views of the happiness, strength, and success of their friendships. The measure of closeness was measured out of 26 and a reflects how well the friends know one another and how many waking hours they spend together [15,45].

Results

Figure :

Do people view their friends more positively than their friends view themselves?

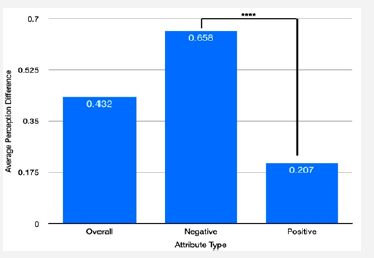

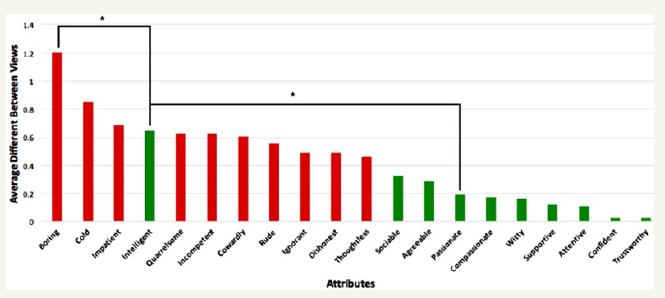

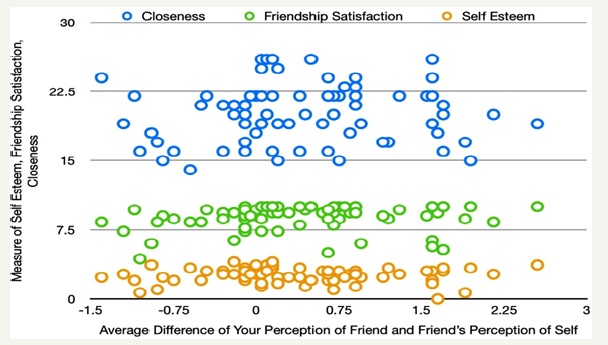

Figures 3 & 4 depict the difference between Participants’ and Friends’ views of one another. The data were analyzed such that a positive difference means that Participants and Friends rated one another more favourably than they rated themselves. Across all attributes and averaged across all participants, the mean perception difference was 0.43 (sd=1.58) (e.g. If a Friend rated themselves as 1 for “confident”, the Participant rated them as 1.43; if a Friend rated themselves as 1 for “quarrelsome”, the Participant rated them as 0.57). Participants and Friends rated one another more favourably than they rated themselves across both positive and negative attributes, but to a greater degree for negative attributes (mean perception difference negative=0.66, sd=1.74; mean perception difference positive = 0.21, sd=1.37; p< 0.0001).

Notably, intelligence yielded the highest perception difference of positive attributes (mean=0.65, sd=1.14), and it was greater than nine other positive attributes (p< 0.5). Participants and Friends rated one another higher than they rated themselves to the highest degree for “boring” (mean=1.20, sd=1.60). Perceptual differences for “boring” were far larger than the perception differences of all other attribute, excluding cold and impatient (p< 0.05). Negative attributes (depicted in red) consistently produced greater perception differences than positive attributes (Murray & Holmes, 1993, 1994) (Figure 4).

Figure 4 : Laser diffraction and Image Analysis bar graphs of ProRoot MTA, Portland cement and Bismuth oxide

How do people view their friends in relation to themselves and in relation to their ideal friends?

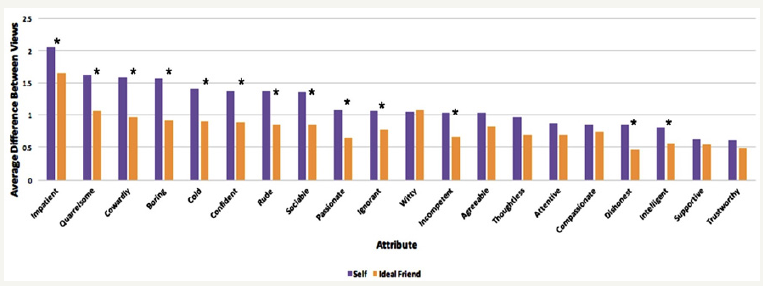

To investigate whether individuals view their friends more as a projection of themselves or as a projection of their ideal friend, two positive differences across each interpersonal attribute for the 94 participants were calculated: Participant’s view of Self - Participant’s view of Friend (s-f) and Participant’s view of Ideal Friend - Participant’s view of Friend (i-f). Across all characteristics, excluding “witty”, participants views of their friends were closer to their ideal friend than to themselves, as depicted by the a difference closer to zero [22,40].

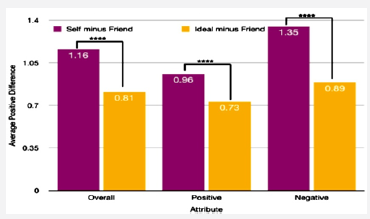

“Sociable” and “incompetent” yielded the greatest differences in s-f and i-f (sociable: mean s-f=1.03, sd=1.04; mean i-f=0.66, sd=0.97, p< 0.0001). The overall s-f mean was 1.16 (sd=1.25), and the i-f mean was 0.81 (sd=1.04, p< 0.0001). Similar results were obtained comparing s-f and i-f within positive and negative attributes. (Figure 5) shows the relation between (s-f) and (i-f) for each attribute, and (Figure 6) shows the relation between (s-f) and (i-f) averaged across positive, negative, and all attributes. This apparent distortion is particularly striking considering that most individuals typically idealize their own attributes [46].

Figure 5 : Positive difference between one’s view of friend and one’s view of oneself (s-f) vs.one’s view of their ideal friend by attribute (i-f).

Figure 6 : Average positive difference between one’s view of friend and one’s view of self (s-f) vs. one’s view of their ideal friend (i-f).

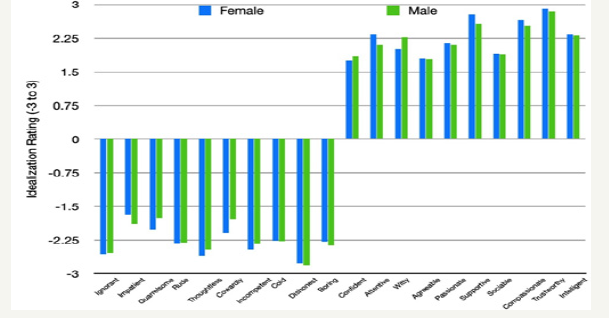

Do men and women have different perceptions of an ideal friend?

For all 20 characteristics, there were no significant differences between ratings of an ideal friend amongst males and females. Negative ratings in (Figure 8) indicate that participants desire an attribute to be uncharacteristic of a friend, and positive ratings indicate that participants desire an attribute to be characteristic of a friend. The average ratings for negative and positive attributes for males were -2.25 (sd=1.13) and 2.22 (sd=1.03), respectively. For females, the averages were -2.31 (sd=0.96) and 2.27 (sd=0.90).

Although differences in ideal attributes were not present across gender analyses, certain trends did appear. Friendships will be denoted as follows: two men = M/M; two women = W/W; one man and one women = W/M; a combination of women who are friends with women and men = W/W & W/M; a combination of men who are friends with women and men = M/M & M/ M. Friends of the opposite sex and friends who are both men reported one another as being more supportive (M/F | p = .005; M/M | p = .04) and compassionate (M/F | p = .01; M/M | p = .02) than friends who are both women.

Friends of the opposite sex reported one another to be more trustworthy than friends who are both women (M/F | p = .03). Women slightly favored attentive and supportive qualities, while men showed preferences for witty and quarrelsome qualities. Correspondingly, men viewed their friends as more quarrelsome (M/M & M/W | p-value = .003) and witty (M/M & M/W | p-value=.02) in comparison to W/W & W/M. Interestingly, men viewed their friends as more compassionate (M/M & M/W | p-value = .02) and supportive (M/M & M/W | p-value = .05) than women viewed their friends, while women reported slightly greater ideals in these areas.

Figure 7 : Idealization ratings of individual attributes amongst females and males.

Figure 8 : Scatter plot correlating perception difference with self-esteem, friendship satisfaction, and friendship closeness.

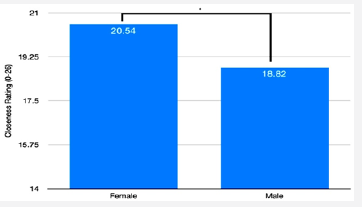

Friends who were both women described their friendships as closer than friends who were both men (W/W | p = .003). Furthermore, women viewed their friendships with either gender as closer than men viewed their friendships with either gender (W/W & W/M | p-value =.04). (See Appendix B) Interestingly, women’s self-esteem was moderately correlated with self-reported negative attributes (r = -0.4), while men’s self-esteem neither correlated with either positive or negative self-reported attributes. When comparing friendships between two women and two men, closeness proved even more characteristic of women’s friendships (W/W = .002). Self-esteem, friendship satisfaction, and closeness did not correlate with levels of idealization across gender or in general

How do self-esteem, friendship satisfaction, and closeness relate to differences in perception or idealization of one’s friends?

No relationship was found between self-esteem, relationship satisfaction, or closeness and levels of idealization of one’s friends. Above-average friendship satisfaction (mean=8.82, sd= 1.37) and self-esteem (mean=2.56, sd= 0.76) did not produce differences in idealization when compared to those who reported below-average self-esteem and friendship satisfaction. When comparing friendship satisfaction and self-esteem to idealization, r-values were all close to zero. The scatter plot in (Figure 10) graphs perception difference on the x-axis and three measures on the y-axis: participants’ ratings of self-esteem (range 0-4), friendship satisfaction (range 0-10), and friendship closeness (range 1-26).

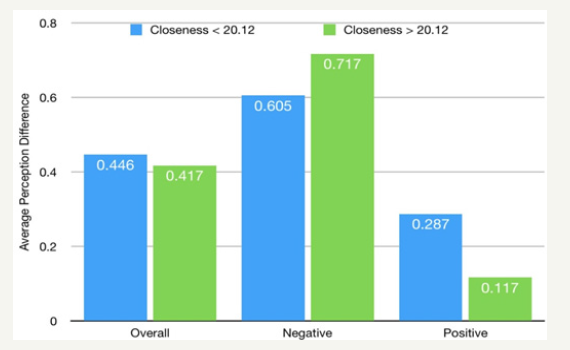

Similarly, no correlation was found between levels of idealization and perceived closeness (Figure 10). The mean perception of closeness was 20.12 (sd= 3.12). The bar graph depicts participants’ perception differences for those rating their friendship closeness less than 20.12 and greater than 20.12. These data were measured for overall, positive, and negative attributes. For positive attributes, those who indicated above-average closeness were not as close to their friends’ views of themselves as were those in the below-average group (above-average mean=0.717, sd=0.96; belowaverage mean=0.605, sd=1.27, p>0.5). When the data were broken down into overall, negative, and positive attributes, there was still no significant difference between the perception difference of those who reported below-average closeness and those who reported above-average closeness.

Figure 9 : Perceived closeness versus perception difference for positive and negative attributes, as well as an aggregate of attributes.

Figure 10 : Average closeness rating amongst men and women (p = 0.35).

Interestingly, while idealization did not predict levels of friendship satisfaction, closeness, or self-esteem, increased friendship satisfaction was positively correlated with increased closeness (r=0.40; women r=.36; men r=0.50). It is also notable that males and females showed no significant difference in selfesteem or level of satisfaction with their friendships, as women typically report lower measures of self-esteem and higher levels of friendship satisfaction [7,47-49] however, (Figure 8) shows that women reported having closer friendships (mean closeness rating=20.54, sd=3.59) than males reported (mean closeness rating = 18.82, sd = 3.75; p=0.035) (Figure 7). These data were calculated using measures of closeness from both same and crosssex friendships (W/W & W/M = 67, M/M & M/ W = 49).

It is noteworthy that friends viewed one another’s negative attributes starkly differently when compared to perceptual differences in positive attributes. As a testament to the idealized nature of friendship constructions, individuals generally viewed their friends even more positively than their friends perceived themselves. In light of the fact that individuals typically see themselves in much more positive, idealized ways than their actual attributes appear to warrant, these results are especially significant [42,46,50,51].

Furthermore, the results of this study suggest that participants’ impressions of their friends reflect a certain level of idealization, seen through perceptual differences in interpersonal attributes. Participants’ impressions converged moderately with their Friends’ self-perceptions, suggesting that some degree of common perception characterizes most close friendships; however, friends were viewed as closer to participants’ ideals than their selfreported attributes.

On average, men’s and women’s perceptions of an ideal friend did not differ. If it is true that individuals select their friends based on idiosyncratic wants, this is not surprising [38,52-54]. Lastly, self-esteem, friendship satisfaction, and closeness did not correlate with levels of idealization across gender or in general. These results differ from trends noted in romantic relationships [22]. As romantic partners are expected to be one closest emotional connection [55]. It is possible that one’s higher expectations of their romantic partner, coupled with increased levels of intimacy, lead to such correlations in romantic relationships, but not in friendship.

Geographic Limitations and Future Directions

Studies have shown that upwards of 50% of close friendships amongst undergraduate students are long-distance (LD), largely due to advances in technological communication [56,57]. While geographically close (GC) friendships provide more received social support than LD friendships, perceived social support is generally equal for GC and LD friendships [58].

Received social support is the help that an individual has actually experienced, such as being given class notes by a friend. Perceived social support is the belief that a friend would offer help, independent of past experiences. An example of this might include receiving emotional support in a time of need. Social (emotional/ informational/instrumental) support is one of the strongest links to positive friendship outcomes. [20,59,60]

The present study was restricted to undergraduate students at Princeton University, meaning only GC friendships were reported. Past research suggests that this likely would not impact this study’s data, as perceived social support is regarded as preferable to received social support, and LD and GC friendships offer equal amounts of perceived support [17]. Therefore, it is assumed that LD friends would produce similar results in a replicated study, excluding the measure of closeness, which includes number of hours spent together. Future work might look to compare results of this study by only reporting on LD friendships.

Demographic Limitations and Future Directions

The nature of Princeton University’s campus may have biased certain measures of interpersonal attributes. For example, intelligence yielded a notably larger perceptual difference amongst Participants and Friends than other positive attributes. It would be interesting to see if a population beyond a competitive university campus would yield the same results. Possible differences may include a reduction in levels of imposter syndrome, which is often linked to reduced impressions of one’s intelligence in comparison to one’s peers [19,61,62].

Additionally, it is noteworthy that measures of friendship satisfaction, self-esteem, and perceptions of closeness have proven to vary across cultures. Diener E & Diener M [63], Samter W & Burleson BR [8] Shaver PR, Murdaya U & Fraley RC [14]. Chen G, Bond MH & Chan SC [64] found that White American students were more willing to report personal information on an array of topics than Asian American students. Yet, separate studies have elicited data that complicate these trends. Both individualistic and collectivist cultures have indicated preferences for emotionally emotive communication [65]. Furthermore found that Canadian and Chinese students did not display differences in measures of friendship closeness. Thus, it is uncertain whether cultural trends of individualism or collectivism would alter self-reported measures of closeness. Future studies could look to draw firmer conclusions of possible differences in reported levels of self-esteem, friendship satisfaction, and perceived closeness by replicating this study in both predominantly collectivist and individualistic cultures, and then comparing results to the present study. Noting Participants’ and Friends’ ethnic backgrounds could also provide more clarity.

Gender Limitations and Future Directions

There has been much debate surrounding whether women’s or men’s friendships are more intimate. Some researchers propose that there exist two pathways

A. Self-disclosure and

B. Shared activities

To developing feelings of closeness in men’s friendships, whereas self-disclosure alone is enough for women to develop feelings of closeness [15,66]. Other researchers have noted that men are aware of the importance of self-disclosure in developing close friendships, but they knowingly choose not to engage in such activities, particularly in friendships with other men [2,12,33,43,67,68,69-72]. In fact, men and women share perceptions of differing levels of intimacy, both relating intimacy back to acts of self-disclosure [73]. In the present study, closeness was defined as a combination of the number of hours Participants and Friends spent together, how well Participants believed to know their Friends, and how well Participants believed their Friends knew them.

In line with previous research, the results of this study suggest that women view their friendships as closer than men do [8,18,28-30,32,34]. Mixed-gendered relationships proved closer than relationships between two men, also corroborating previous research [74]. In contrast to previous research, support and compassion did not correlate with increased feelings of trustworthiness or closeness [66,75,76]. In fact, Friendship between two women were described as closer than friendships between two men, despite women’s perceived lower levels of compassion and support in their friends.

Women slightly favoured attentive and supportive qualities, while men showed slight preferences for witty and quarrelsome attributes. Correspondingly, men viewed their friends as more quarrelsome and witty. These results may relate to the fact that women tend to be more emotionally communicative individuals, while men are more inclined to bond over shared activities and debate. [77,78,79].

Interestingly, men viewed their friends as more compassionate and supportive than women viewed their friends, despite the fact that women reported slightly greater ideals in these areas. This is even more noteworthy because relationships between men have been said to be less supportive and intimate than friendships between women [28], however, it is important to note that friendships between men do indeed involve high levels of love and support, though communicated differently than in friendships between women [80,81]. Furthermore, despite lower measures of compassion and support, which are often linked to friendship closeness, women reported having closer friendships than men. When comparing friendship’s between two women and two men, closeness proved even more characteristic of friendships between two women.

The present research makes a contribution toward analysis of perceptions of closeness across genders. Future work might look to incorporate more in depth questions about shared activities and closeness to better account for closeness predictors in men, which have proven to show correlate with closeness in men’s friendships [10,82]. Furthermore, more thorough questions concerning attributes of trustworthiness, supportiveness, and compassion should be considered. Prototypical interaction models that relate to friendship satisfaction Hassebrauck [83], Hassebrauck & Fehr B [6] and closeness. Fehr B [84] may offer further insight into why women tend to report having closer friendships than men do. In a study conducted by Fehr B [84], compassion and support correlated with increased feelings of closeness amongst men and women. Both of these attributes are linked often to increased feelings of trust amongst friends [75,85]. For example, rather than asking Participants and Friends to solely report how trustworthy one another are, it may prove beneficial to include a variety of questions that deal with more intricate qualities of trustworthiness.

General Limitations and Future Directions

As with all surveys and questionnaires, confounding factors of under-coverage, convenience sampling, nonresponsive bias, voluntary response bias, and social desirability bias are to be expected [13,86,47]. The setup for this experiment aimed to reduce such biases by incorporating random sampling; The Survey Research Centre at Princeton University distributed this study’s survey to 350 randomly selected undergraduate students to reduce the effects of these biases. Furthermore, questions were worded in a neutral manner and were randomized.

Lastly, the co relational nature of these results restricts the ability to generalize why participants idealize their friends. A longitudinal study would offer a better space to analyze the benefits of idealization in friendships. Other studies have noted certain changes friendships undergo over time, and this would be highly relevant to future studies [87-89]. Next steps include studying the overlaps between self-esteem, perceived closeness, and overall friendship satisfaction and idealization’s utility in either continued satisfaction or eventual dissatisfaction in close friendships. Furthermore, future studies should assess low, medium, and high levels of friendship satisfaction, self-esteem, and closeness benchmarks. The present study measured for broader categories of “low” and “high”, possibly underscoring certain correlations between these categories and idealization levels.

Disclosures

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge support of this research from Justin Jungé, Dong Won Oh, Johannes Haushofer, IRB, The Survey Research Centre at Princeton University, and our participants.

References

- Samter W & Burleson BR (1998) The role of communication in samesex friendships: A comparison among African-Americans, Asian- Americans, and Euro-Americans. Paper presented at the International Conference on Personal Relationships, Saratoga Springs, NY, USA 53(3): 265-284.

- Perlman D & Fehr B (1987) The development of intimate relationships. In D Perlman & S Duck (Eds.), Intimate relationships: Development, dynamics and deterioration. Sage, Beverly Hills, CA, USA, p. 13-42.

- Berscheid, E & Walster EH (1978) Interpersonal attraction (2nd edn). Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA, USA.

- Berscheid E, Snyder M & Omoto AM (1989) Issues in studying close relationships: Conceptualizing and measuring closeness. In C.Hendrick (Ed.) Review of personality and social psychology 10: 63-91.

- Buss DM (1989) Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 12(1): 1-49.

- Hassebrauck M & Fehr B (2002) Dimensions of relationship quality. Personal Relationships 9(3): 253-270.

- Thomas JJ & Daubam KA (2001) The Relationship between Friendship Quality and Self-Esteem in Adolescent Girls and Boys. Sex Roles 45(1-2): 53-65.

- Feeney JA & Noller P (1991). Attachment style and verbal descriptions of romantic partners. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 8(2): 187-215.

- Candy SG, Troll LE, & Levy SG (1981) A developmental exploration of friendship functions in women. Psychology of Women Quarterly 5(3): 456-472

- Wright PH (1982) Men’s friendships, women’s friendships and the alleged inferiority of the latter. Sex Roles 8(1): 1-20.

- Murray SL & Holmes JG (1993) seeing virtues in faults: Negativity and the transformation of interpersonal narratives in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 65(4): 707-722.

- Floyd K (1997) Brotherly love: II. A developmental perspective on liking, love, and closeness in the fraternal dyad. Journal of Family Psychology 11(2): 196-209

- Kalton Graham & Schuman Howard (1982) The Effect of the Question on Survey Responses: A Review. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (General) 145(1): 42-73.

- Shaver PR, Murdaya U, Fraley RC (2001) Structure of the Indonesian emotion lexicon. Asian Journal of Psychology 4(3): 201-224.

- Camarena P, Sarigiani P, Peterson A (1990) Gender-specific pathways to intimacy in early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 19(1): 19-32.

- Gächter S, Starmer C and Tufano F (2015) Measuring the Closeness of Relationships: A Comprehensive Evaluation of the ‘Inclusion of the Other in the Self’ Scale PLOS ONE, 10(6): e0129478.

- Norris FH & Kaniasty K (1996) Received and perceived social support in times of stress: A test of the social support deterioration deterrence model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 71(3): 498-511.

- Fehr B (1996) Friendship processes. Sage, Newbury Park, CA, USA.

- Craddock S, Birnbaum M, Rodriguez K, Cobb C, Zeeh S (2011) Doctoral students and the impostor phenomenon: Am I smart enough to be here? Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice 48(4): 429-442.

- Forster LE, Stoller EP (1992) The impact of social support on mortality: A seven-year follow-up of older men and women. Journal of Applied Gerontology 11(2): 173-186.

- Bowlby J (1977) The making and breaking of affectional bonds. British Journal of Psychiatry 130: 201-210.

- Murray SL, Holmes JG & Griffin DW (1996) The benefits of positive illusions: Idealization and the construction of satisfaction in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 70(1): 79-98.

- Bowlby J (1982) Attachment and loss (Vol 1) Hogarth Press, London, UK.

- Dion KL & Dion KK (1975) Self-esteem and romantic love. Journal of Personality 43(1): 39-57.

- Mathes EW & Moore CL (1985) Reik’s complementarity theory of romantic love. Journal of Social Psychology, 125(3): 321-327.

- Rosenberg M (1965) Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton University Press. USA

- Sapadin LA (1988) Friendship and gender: Perspectives of professional men and women. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 5(4): 387- 403.

- Bank BJ & Hansford SL (2000) Gender and friendship: Why are men’s best same-sex friendships less intimate and supportive? Personal Relationships 7(1): 63-78.

- Fischer J & Narus L (1981) Sex roles and intimacy in same sex and other sex relationships. Psychology of Women Quarterly 5(3): 444-455.

- Reis HT (1988) Gender effects in social participation: Intimacy, loneliness, and the conduct of social interaction. In R.Gilmour & S.Duck (Eds.), The emerging field of personal relationships. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, USA, pp. 91-105.

- Reis HT (1990) The role of intimacy in interpersonal relations. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 9(1): 15-30.

- Reis HT (1998) Gender differences in intimacy and related behaviors: Context and process. In D. L.Canary & K.Dindia (Eds.), Sex differences and similarities in communication. Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ,, USA, pp. 203- 231.

- Reis HT & Shaver P (1988) Intimacy as an interpersonal process. In SW Duck (Ed.), Handbook of personal relationships. Wiley, Chichester, England, pp. 367-389.

- Sharabany R, Gershon R, Hofman JE (1981) Girlfriend, boyfriend: Age and sex differences in intimate friendship. Developmental Psychology 17(6): 800-808.

- Leary T (1957) Interpersonal diagnosis of personality. Ronald Press, New York, USA.Li HZ (2002) Culture, gender and self-close other(s) connectedness in Canadian and Chinese samples. European Journal of Social Psychology 32: 93-104.

- Wiggins JS (1979) A psychological taxonomy of trait-descriptive terms: The interpersonal domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 37(3): 395-412.

- Aron A & Aron, EN (1986) Love and the expansion of self: Understanding attraction and satisfaction. Hemisphere, Washington, DC, USA

- Cann A (2004) Rated Importance of Personal Qualities Across Four Relationships. Journal Of Social Psychology 144(3): 322-334.

- Adams G & Anderson SL (2004) The cultural grounding of closeness and intimacy. In: D Mashek & A Aron (Eds.), Handbook of closeness and intimacy. Mahwah, Erlbaum, NJ, USA, pp. 321-339.

- Swann WB (1983) Self-verification: Bringing social reality into harmony with the self. Psychological perspectives on theself 2: 33-66.

- Aron A, Aron, EN, Smollan D (1992) Inclusion of Other in the Self Scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. Journal of Personality And Social Psychology 63(4): 596-612.

- Alicke MD (1985) Global self-evaluation as determined by the desirability and controllability of trait adjectives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 49(6): 1621-1630.

- Altman I & Taylor DA (1973) Social penetration: The development of interpersonal relationships. Holt, Rinehart & Winston, New York, USA.

- Robins RW, Hendin HM, Trzesniewski KH (2001) Measuring Global Self-Esteem: Construct Validation of a Single-Item Measure and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 27(2): 151-161.

- Cheung Elaine O, Gardner Wendi L (2016) With a little help from my friends: Understanding how social networks influence the pursuit of the ideal self. Self and Identity 15(6): 662-682.

- Taylor SE & Brown JD (1988) Illusion and well-being: A social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychological Bulletin, 103(2): 193-210.

- Helwig NE, Ruprecht MR (2017) Age, gender, and self-esteem: A sociocultural look through a nonparametric lens. Archives of Scientific Psychology 5(1): 19-31.

- Jones and Diane C (1991) Friendship Satisfaction and Gender: An Examination of Sex Differences in Contributors to Friendship Satisfaction. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 8(2): 167-185.

- Mendelson MJ & Aboud FE (1999) Measuring friendship quality in late adolescents and young adults: McGill Friendship Questionnaires. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue canadienne des sciences du comportment 31(2): 130-132.

- Brown J D (1986) Evaluations of self and others: Self-enhancement biases in social judgment. Social Cognition 4(4): 353-376.

- Greenwald AG (1980) The totalitarian ego: Fabrication and revision of personal history. American Psychologist 35(7): 603-618.

- Davis KE & Todd ML (1985) Assessing friendship: Prototypes, paradigm cases, and relationship description. In S Duck & D Perlman (Eds.), Understanding personal relationships: An interdisciplinary approach p. 17-38.

- Tooby J, Cosmides L (1996) Friendship and the Banker’s Paradox: Other pathways to the evolution of adaptations for altruism. In WG Runciman & JM Smith (Eds.), Evolution of social behaviour patterns in primates and man. Proceedings of The British Academy 88: 119-143.

- Wright PH (1984) Self-referent motivation and the intrinsic quality of friendship. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 1(1): 115-130.

- Hazan C & Shaver P (1987) Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 52(3): 511-524.

- Dellmann-Jenkins M, Bernard-Paolucci TS, Rushing B (1994) Does distance make the heart grow fonder? A comparison of college students in long-distance and geographically-close dating relationships. College Student Journal 28: 212-219.

- Guldner GT, Swensen CH (1995) Time spent together and relationship quality: Long-distance relationships as a test case. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 12(2): 313-320.

- Weiner ASB, Hannum JW (2012) Differences in the quantity of social support between geographically close and long-distance friendships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 30: 662-672.

- House JS (1981) Work stress and social support. Reading, Addison- Wesley, England, UK.

- Siebert DC, Mutran EJ, Reitzes DC (1999) Friendship and social support: The importance of role identity to aging adults. Social Work 44(6): 522- 533.

- Cokley K, Awad G, Smith L, Jackson S, Awosogba Hurst A, et al. (2015) The Roles of Gender Stigma Consciousness, Impostor Phenomenon and Academic Self- Concept in the Academic Outcomes of Women and Men. Sex Roles 73(9-10): 414-426.

- Sakulku J, Alexander J (2011) The Impostor Phenomenon, International Journal of Behavioral Science 6(1): 73-92.

- Diener E, Diener M (2009) Cross-Cultural Correlates of Life Satisfaction and Self-Esteem. Culture and Well Being, pp 71-91.

- Chen C, Bond MH, Chan SC (1995) The Perception of Ideal Best Friends by Chinese Adolescents. International Journal of Psychology 30(1): 91- 108.

- Burleson BR (2003) The experience and effects of emotional support: What the study of cultural and gender differences can tell us about close relationships, emotion, and interpersonal communication. Personal Relationships 10(1): 1-23.

- Helgeson VS, Shaver P, Dyer M (1987) Prototypes of intimacy and distance in same-sex and opposite-sex relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 4(2): 195-233.

- La Gaipa JJ (1979) A developmental study of the meaning of friendship in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence 2(3): 201-213.

- Reis HT & Patrick BC (1996) Attachment and intimacy: Component processes. In: ET Higgins & AW Kruglanski (Eds). Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles. Guilford Press, New York, USA, pp. 523- 563.

- Swain SO (1989) Covert intimacy: Closeness in men’s friendships. In: BJ Risman & P Schwartz (Eds.), Gender in intimate relationships Wadsworth Publishing, Belmont, CA, USA, pp. 71-86.

- Wood JT (1997) Gendered lives: Communication, gender, and culture (2nd edn), Wadsworth, Belmont, CA, USA.

- Wood JT (2000) Gender and personal relationships. In: S Hendrick & C Hendrick (Eds.), Close relationships: A sourcebook. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, pp. 301-313.

- Wood JT & Inman CC (1993) In a different mode: Masculine styles of communicating closeness. Journal of Applied Communication Research 21(3): 279-295.

- Reis HT, Senchak M, Solomon B (1985) Sex differences in the intimacy of social interaction: Further examination of potential explanations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 48(5): 1204-1217.

- Clark ML & Ayers M (1993) Friendship expectations and friendship evaluations: Reciprocity and gender effects. Youth and Society 24(3): 299-313.

- Holmes JG (2002) Interpersonal expectations as the building blocks of social cognition: An interdependence theory perspective. Personal Relationships 9(1): 1-26.

- Monsour M (1992) Meanings of intimacy in cross and same sex friendships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 9(2): 277-295.

- Caldwell M & Peplau L (1982) Sex differences in same-sex friendship. Sex Roles 8(7): 721- 732.

- Duck S & Wright PH (1993) Reexamining gender differences in samegender friendships: A close look at two kinds of data. Sex Roles 28(11- 12): 709-727.

- Reid HM & Fine GA (1992) Self-disclosure in men’s friendships: Variations associated with intimate relations. In: PM Mardi (Ed.), Men’s friendships 2: 132-152.

- Mormon MT & Floyd K (1998) “I love you, man”: Overt expressions of affection in male-male interaction. Sex Roles 38(9-10): 871-881.

- Wellman B (1992) Men in networks: Private communities, domestic friendships. In: P Nardi (Ed.), Men’s friendships 2: 74-114.

- Wright PH (1988) Interpreting research on gender differences in friendship: A case for moderation and a plea for caution. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 5(3): 367- 373.

- Hassebrauck M (1997) Cognitions of relationship quality: A prototype analysis of their structure and consequences. Personal Relationships 4(2): 163-185.

- Fehr B (2004) Intimacy Expectations in Same-Sex Friendships: A Prototype Interaction-Pattern Model. Journal Of Personality And Social Psychology 86(2): 265-284.

- Holmes JG & Rempel JK (1989) Trust in close relationships. In C.Hendrick (Ed). Review of personality and social psychology: Close relationships 10: 187-219.

- Nederhof Anton J (1985) Methods of coping with social desirability bias: A review. European Journal of Social Psychology. 15(3): 263-280.

- Hartup WW & Stevens N (1997) Friendships and adaptation in the life course. Psychological Bulletin 121(3): 355-370.

- Matthews S (1986) Friendships through the life course: Oral biographies in old age. Sage, Beverly Hills, CA, USA.

- Rawlins WK (1994) Being there and growing apart: Sustaining friendships through adulthood. In DJ Canary & L Stafford (Eds.), Communication and relational maintenance. Academic Press, New York, pp. 275- 294.

© 2018 Samantha Smith. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)