- Submissions

Full Text

Orthopedic Research Online Journal

The Clinical Relevance of Assessing and Treating Breathing Muscles to Decrease or Eliminate Low Back Pain: A Case Study

Cleve Carter*, Jaketta Murphy and Steven Justice

Department of Physical Therapy, College of Health Sciences, Alabama State University, USA

*Corresponding author: Cleve Carter, Alabama State University, College of Health Sciences, Department of Physical Therapy, 915 South Jackson Street, Montgomery, AL 36104, USA

Submission: October 18, 2022;Published: November 07, 2022

ISSN: 2576-8875 Volume10 Issue1

Abstract

Background and purpose: It is paramount that physical therapists assess and/or treat primary and secondary muscles of breathing that could be dysfunctional or impaired resulting in low back pain. The purpose of this case study is to highlight the clinical relevance and outcomes of assessing and treating primary and secondary muscle of breathing with patients who have been referred to physical therapy with a medical diagnosis of low back pain.

Method and procedures: A 66-year-old male patient presented to outpatient physical therapy with a report of low back pain. To determine the effects of the treatments, the patient was examined using movement analysis and outcome measurement tools such as the Global Rating of Change (GRoC) scale and the Oswestry Low Back Pain Questionnaire. The patient attended physical therapy sessions over the duration of 4 weeks as needed (PRN) including the date of initial evaluation. The patient actively participated in the creation of the current goal: Eliminate pain, resume exercise.

Conclusion: On discharge assessment, the patient reported a reduced pain level during movement analysis. The patient made excellent progress and demonstrated marked improvements with thoracolumbar spine and proximal extremities functional range of motion.

Keywords: Physical therapy; Manual therapy; Breathing; Muscles; Low back pain; Inspiratory muscles

Introduction

Chronic Low Back Pain (CLBP) is a very common diagnosis across the United States as well as other nations, with over 65 million reported cases [1,2]. It is described as low back pain that has been persistent for at least three months and has resulted in accumulated pain on at least half the days in the last six months [3]. Low back pain has been associated with being one of the top ten burden injuries and diseases with leading connections to decreased employed populations, inactivity, and disability- adjusted years of life [1,2

Low back pain has been categorized into two categories of knowledge, specific vs. nonspecific CLBP. Specific causes of CLBP are diagnosed less commonly and defined as signs and symptoms of specific pathophysiologic mechanisms such as: herniated disk, infections, arthritis, fracture, traumatic musculature event etc. Non-specific CLBP is noted as axial or mechanical dysfunctions caused by events that are unknown. Several physiological factors contribute to causes of CLBP, including: congenital skeletal irregularities, traumatic injuries, degenerative problems, spinal cord problems and recent literature reports impaired primary and secondary breathing musculature affects CLBP as well [2,4,5].

Treatment of low back pain can be as general or specific as the pain itself. According to the literature review, Finta et al. [2] reported that previous studies specified the impact of a variety of training on CLBP, but addressing diaphragm, and secondary breathing musculature, strengthening training had not been deemed yet as a solution. Beeckmans et al. [1] interventions stated that inspiratory muscles, such as the diaphragm, play a key role in both respiration and spinal control. Therefore, diaphragm dysfunctions are often related to Low Back Pain (LBP) [1,2].

However, little is known about the association between the presence of LBP and the presence of Respiratory Disorders (RD). Another study, Boyle et al, reported that the diaphragm is involved in the control of postural stability during sudden voluntary movement of the limbs via clinical experience that utilized Balloon Blow Exercise (BBE). Janssens et al reported that the postural stability of the trunk can be improved by strengthening the diaphragm muscle and suggested that pain intensity may be decreased by diaphragm training. The study interventions stated that researchers strengthened the diaphragm of the participants via utilization of a POWER breathe device that gave opposition and or resistance to the subjects’ ability to inhale. They found that the 8-week-long intensive diaphragm training increased respiratory muscle strength, that proprioceptive use changed in a positive way, and that the participants completed an Oswestry Disability Index and reported a decrease in low back pain severity [6].

Global and local lumbar stabilizers such as the diaphragm, quadratus lumborum, latissimus dorsi, and iliopsoas are directly related to lumbar stability and instability which when impaired gears decreased trunk and hip mobility and CLBP diagnosis [2,7]. The connections between the spine and primary/secondary breathing musculature details the outcome of potential cause and effect of CLBP. Assessing and treating primary and secondary muscles of breathing in patients with low back pain is not a novel idea, however, readily available literature concerning the clinical relevance and outcomes of this idea is more recently pressing. This case study is aimed to provide clinical insight into the relevance of assessment and treatment of primary and secondary muscles of breathing in patients with low back pain via pain scale, nociceptive response to palpation, movement analysis, and Oswestry Low Back Pain Outcome Measurement Tool. The goal of this research is to examine non pharmaceutical approaches to reduce symptoms and prevent CLBP, which in this case capitalizes experienced manual therapy treatments as an evidence-based solution.

Method and Procedures

A 66-year-old male patient presented to outpatient physical therapy with a report of onset of low back pain. The patient stated that it started as “stiffness and pulling sensation” with gradual numbness and tingling down the left lower extremity just past the calf muscles. The clinician discussed the examination, evaluation, and plan of care process with the patient. The clinician also obtained permission to use gathered data to write a case report. To determine the effects of the treatments, the patient was examined using movement analysis and outcome measurement tools such as the Global Rating of Change (GRoC) scale and the Oswestry Low Back Pain Questionnaire.

On the initial evaluation the patient reported (1/10) pain level. The patient reported that his usual pain over the past week was (6/10), pain at its worst over the past week was (7/10), and best pain level over the past week was (3/10). The patient stated that pain increases with prolonged sitting, standing, walking, and running greater than 30 minutes. The clinician conducted movement analysis consisting of repeated movements of the lumbar spine and active movements while the patient was standing as well as palpation of musculature during initial evaluation.

The clinician conducted thoracolumbar repeated movements including Forward Bending (FB) x 2 with patient report of bilateral hamstring musculature tightness. Side-bending to the left (SBL) x 2 with report of “nagging” pain/discomfort along posterior rim of the iliac crest. Left hip internal rotation Passive Range of Motion (PROM) was noted to be painful where right hip internal rotation PROM was pain free. Active movement analysis of the patient was conducted while the patient was standing.

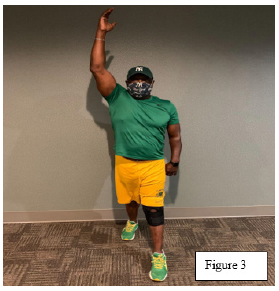

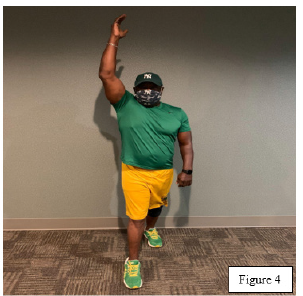

The clinician instructed a movement analysis in a standing position including: Right Lower Extremity (RLE) hip flexion and Left Upper Extremity (LUE) shoulder elevation (Figure 1) that patient reports moderate aching pain along the left iliac crest region. Left Lower Extremity (LLE) hip flexion and LUE shoulder elevation (Figure 2) that patient reports severe aching pain along the left iliac crest region. LLE hip flexion and RUE shoulder elevation (Figure 3) that patient reports moderate aching pain along the left iliac crest region. RUE shoulder elevation and RLE flexion (Figure 4) the patient reports pain free movement during standing. The patient demonstrated positive nociceptive response to palpation of bilateral diaphragm, left quadratus lumborum musculature, left latissimus dorsi musculature, left iliopsoas musculature, and the left iliac crest region.

Figure 1:

Figure 2:

Figure 3:

Figure 4:

The patient scored 14/50 or 28% on the Oswestry Low Back Pain Index indicating a moderate disability as the patient experienced more pain and difficulty with sitting, lifting, and standing. The GRoC was not administered on the initial evaluation; however, it was conducted during the discharge assessment session. The patient attended physical therapy sessions over the duration of 4 weeks PRN including the date of initial evaluation. The patient actively participated in the creation of the current goal: Eliminate pain, resume exercise. Patient education is an intervention utilized that showed to be very beneficial for the patient. The patient received education on involved anatomy with use of an iPad for visual learning. Education on indications and benefits of performing Home Exercise Program (HEP) with handout provided and reviewed with the patient allowed for a more holistic understanding of physical therapy plan of care by the patient.

For 4 weeks, the patient benefited from therapeutic exercise and manual therapy in the clinic while adhering to the home exercise program. The patient participated in therapeutic exercises consisting of bilateral standing hamstring stretches, bilateral seated hip rotator stretches, and chair-guided squats to improve patient muscular flexibility, strength, and endurance. The patient underwent manual therapy techniques that included; bilateral iliac crest release, erector spinae muscle play, thoracolumbar myofascial release, left latissimus dorsi release, bilateral diaphragm release, and left hip posterior glide joint mobilizations grade I, II, and IV as to improve soft tissue mobility and joint mobility with functional activities of daily living performance. The patient was provided education on performance of the aforementioned home exercise program along with a handout that included the standing hamstring stretches, hip rotator stretches, and chair-guided squats done in the clinic. By visit #4, the patient had made good progress towards patient goals of eliminating pain and resuming pain free exercise.

Results

On discharge assessment (4th visit), the patient reported a reduced 0/10 pain level. The Oswestry Low Back Pain Index was reassessed and the patient improved significantly scoring 1/50 or 2% indicating minimal disability. Per Global Rating of Change (GRoC), the patient reported, “A great deal better” with overall functional performance with functional activities of daily living from the time initial physical therapy interventions began until now. The patient stated that he is no longer experiencing stiffness, pulling sensation, nor numbness and tingling in the left lower extremity. The patient reports that he has been able to tolerate prolonged sitting, standing, walking, and running greater than 30 minutes without pain. On the day of discharge, the standing movement analysis, repeated lumbar movements analysis, and palpation screen was completed again. The patient was able to complete all standing and repeated lumbar movements pain-free without radicular symptoms as compared to initial evaluation. The patient also demonstrated negative nociceptive response to palpation of bilateral diaphragm, left quadratus lumborum musculature, left latissimus dorsi musculature, left iliopsoas musculature, and the left iliac crest region as compared to initial evaluation. The patient made excellent progress and demonstrated marked improvements with thoracic-lumbar spine functional ROM/flexibility, soft tissue mobility, and joint mobility. The patient achieved 100% of established goals by the 4th visit.

Discussion

The results support the effectiveness of assessing and treating breathing muscles in patients with low back pain. Previous research has exhibited that an increase in intra-abdominal pressure provides added stability; therefore, controlling of the lumbar spine, which is needed to unload the spine during balance and loading tasks [8,9]. The diaphragm has been shown to contribute to postural control by increasing intra-abdominal pressure and possibly via its anatomical connection to the spine [8,9]. Our findings showed that the enhanced inspiratory muscle strength contributed greatly to the overall function of the lower back and decrease in pain during functional movement. Not assessing or addressing primary and secondary muscles of breathing could result in overlooking musculoskeletal dysfunctions which could lead to chronic low back pain or referred pain that can easily result in functional limitations with prolonged standing, sitting, and or walking. In low back pain cases, symptoms are often localized to the lumbo pelvic hip complex. One must understand the anatomy of muscles of respiration and their origin/attachment sites to realize how muscles of respiration like the diaphragm and accessory muscles such as the latissimus dorsi can cause low back pain in an individual.

Conclusion

The results showed that assessing and treating breathing muscles can be effective in treating a patient with complaints of low back pain. The findings of the research may aid in revealing why individuals with breathing problems have an increased risk of developing LBP and why individuals with LBP are also more likely to develop breathing problems [10]. The manual therapy techniques coupled with the patient’s adherence to their home exercise program decreased the patient’s pain drastically after 4 weeks while also improving patient functionality. These results are not generalizable to all patients who may present to physical therapy with complaints of low back pain. We believe that our data provides justification for further exploration of the relationship between LBP and training of inspiratory musculature, with rise to noted limitations in research. Future research could include assessing subjects primary and secondary breathing musculature as a common part in physical therapy evaluations. In addition, further research could include a larger more diverse sample size.

References

- Beeckmans N, Vermeersch A, Lysens R, Wambeke PV, Goossens N, et al. (2016) The presence of respiratory disorders in individuals with low back pain: A systematic review. Manual Therapy 26: 77-86.

- Finta R, Nagy E, Bender T (2018) The effect of diaphragm training on lumbar stabilizer muscles: A new concept for improving segmental stability in the case of low back pain. Journal of Pain Research 11: 3031-3045.

- Roussel N, Nijs J, Truijen S, Vervecken L, Mottram S, et al. (2009) Altered breathing patterns during lumbopelvic motor control tests in chronic low back pain: a case-control study. European Spine Journal 18(7): 1066-1073.

- Bordoni B, Zanier E (2013) Anatomic connections of the diaphragm influence of respiration on the body system. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare 6: 281-291.

- Kolář P, Šulc J, Kynčl M, Sanda J, Cakrt O, et al. (2012) Postural function of the diaphragm in persons with and without chronic low back pain. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 42(4): 352-362.

- Janssens L, McConnel A, Pijnenburg M, Claeys K, Goossens N, et al. (2015) Inspiratory muscle training affects proprioceptive use and low back pain. Medicine & Science in Sports Exercise 47(1): 12-19.

- Kyndall LB, Josh O, Cynthia L (2022) The value of blowing up a balloon. North American Journal of Sports Physical Therapy 5(3): 179-188.

- Hodges PW, Eriksson AE, Shirley D, Gandevia SC (2005) Intra-abdominal pressure increases stiffness of the lumbar spine. J Biomech 38 (9): 1873-1880.

- Hodges PW, Gandevia SC (2000) Changes in intra-abdominal pressure during postural and respiratory activation of the human diaphragm. J Appl Physiol 89(3): 967-976.

- Smith MD, Russell A, Hodges PW (2014) The relationship between incontinence, breathing disorders, gastrointestinal symptoms, and back pain in women: a longitudinal cohort study. Clin J Pain 30(2): 162-167.

- Helen B, Joseph E (2022) Breathing pattern disorders and functional movement. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy 9(1): 28-39.

- Mohan V, Paungmali A, Sitilerpisan P, Hashim UF, Mazlan MB, et al. (2018) Respiratory characteristics of individuals with non-specific low back pain: A cross-sectional study. Nursing & Health Sciences 20(2): 224-230.

- Russo M, Deckers K, Eldabe S, Kyle K, Chris G, et al. (2017) Muscle control and NON-SPECIFIC chronic low back pain. Neuromodulation: Technology at the Neural Interface 21(1): 1-9.

- Terada M, Kosik K, McCain R, Gribble P (2016) Diaphragm contractility in individuals with chronic ankle instability. Medicine Science in Sports Exercise 48(10): 2040-2045.

© 2022 Cleve Carter. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)