- Submissions

Full Text

Orthopedic Research Online Journal

Preoperative Anxiety Predicts Dissatisfaction with the Results of Lumbar Intervertebral Discectomy

Tõnu Rätsep* and Liisa Kams

Department of Neurology and Neurosurgery, University of Tartu, Estonia

*Corresponding author: Tõnu Rätsep, Department of Neurosurgery, Tartu University Hospital, L.Puusepa 8, 50406 Tartu, Estonia

Submission: December 17, 2021;Published: January 04, 2022

ISSN: 2576-8875 Volume9 Issue1

Abstract

Background: Preoperative anxiety may lead to increase in morbidity and postoperative pain in patients with lumbar disc herniation. A prospective study was conducted to evaluate the incidence, determinants and prognostic value of preoperative anxiety in patients scheduled for lumbar discectomy.

Methods: The prospective observational study was performed on 100 patients. Visual analog scale and Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale (APAIS) were used to evaluate preoperative anxiety level. The clinical outcome and overall satisfaction with the results of the treatment was evaluated after six months.

Results: Most of the patients (86%) described preoperative anxiety and APAIS scores were significantly higher for surgery than for anesthesia. Patients with higher anxiety values experienced higher pain intensity and were less informed about the disease. APAIS-anxiety scores were significantly correlated with the desire for information according to APAIS-knowledge values (r=0.59; p<0.0001). Female gender was the only factor that proved to be significantly related to APAIS scores in a multivariate model (p=0.04). Preoperative anxiety was not correlated with postoperative pain intensity, however, the patients with higher preoperative APAIS scores were more frequently not satisfied with the results of the treatment (p=0.03).

Conclusion: The present study showed that preoperative anxiety is common before lumbar discectomy and female gender is the most important contributor to higher anxiety values. Preoperative anxiety is related to the desire for information, pain intensity and the extent of knowledge about the disease and associated with postoperative dissatisfaction with the treatment results.

Keywords: Preoperative anxiety; Lumbar discectomy; Radiculopathy; Lumbar disc herniation

Abbreviations: APAIS: Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale; LDH: Lumbar Disc Herniation; LD: Lumbar Discectomy; VAS: Visual Analog Scale; ODI: Oswestry Disability Index; BMI: Body Mass Index

Background

Preoperative anxiety can be described as an unpleasant state of tension or uneasiness that results from a patient’s doubts or fears before an operation [1]. Preoperative anxiety is common in surgical patients - the incidence as high as 94% has been described [2]. Pain, disability, gender, age, previous surgery or anesthesia experience, education and the patient’s information requirements are among the potential risk factors for the development of elevated preoperative anxiety [3,4]. Patients scheduled for spinal or neurosurgical operations are also likely to suffer from preoperative anxiety, which may lead to increase in morbidity and mortality, frequent postoperative pain and increased anesthetic requirements [5-8].

Radiculopathy caused by Lumbar Disc Herniation (LDH) is a leading reason for lumbar spine surgery and despite predominantly positive results, Lumbar Discectomy (LD) is not always successful in terms of pain relief and functional improvement of the patients [9,10]. Thus, the analysis of clinical factors and patient characteristics, potentially influencing postoperative outcomes of LD, is crucial. Preoperative anxiety has been described among the prognostic factors for the persistence of pain and worse patient-reported outcomes after LD [9,11-14]. In 2017, Dorow et al. [9] explored the socio-demographic, medical, occupational and psychological variables associated with pain intensity in lumbar disc surgery patients and found that age, anxiety and dysfunctional coping behavior were significantly associated with worse postoperative pain [9]. In a recent meta-analysis Theunissen et al. [15] also emphasized the association of preoperative anxiety and catastrophizing with postsurgical pain after LD. However, patient satisfaction is another important criterion of treatment success and a significant correlation between preoperative anxiety and postoperative satisfaction with treatment results has been verified in patients with spinal stenosis and spondylolisthesis [16]. Nevertheless, the relationship between preoperative anxiety and patient satisfaction with the results of LD is unclear.

Information about the incidence, potential risk factors and prognostic value for preoperative anxiety before LD is controversial. The present study aims to: 1) evaluate the level of preoperative anxiety in patients scheduled for LD; 2) assess the factors potentially contributing to anxiety before LD; 3) evaluate the importance of anxiety as a prognostic factor for postoperative pain and dissatisfaction with the treatment results after LD.

Methods

Study population

We evaluated prospectively a consecutive sample of patients scheduled for LD, admitted to the department of neurosurgery. The patients were included in the study if they had radicular pain with or without neurologic deficits due to LDH. The existence of LDH (protrusion, extrusion, or sequestration) was verified by magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography. Exclusion criteria included cauda equina syndrome, acute pain and severe radicular deficits requiring urgent operation, cognitive deficits that prevented effective communication, and general contraindications to elective surgery. All patients were operated upon using a standard posterior microdiscectomy approach. Informed consent was obtained from all participating individuals and the study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Tartu (285/ T-1)

Data collection

The patients provided basic information about sociodemographic and disease characteristics. Visual analog scales (VAS-p), ranging from 0 to 100, were used for assessment of pain (indicating average radicular or lumbar pain in the last 2 days) and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) scores [17] were used to evaluate functional disability of the patients.

The VAS for anxiety (VAS-a) and Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale (APAIS) [18] were used to evaluate the current anxiety level on the day before the operation. The VAS-a scale was applied by asking the patients to indicate their anxiety level using a number between 0 (no anxiety) and 100 (highest anxiety). The APAIS was used to evaluate the level of anxiety of the patients at the time of the interview. The APAIS comprised 6 questions where each component was scored on a Likert scale from 1 to 5 (where 1 was none and 5 most anxiety or highest need for information). The APAIS score (APAIS-total) was then divided into the anxiety component (APAIS-a, 4 questions with a maximum score of 20) and the knowledge or “need-for-information” component (APAIS-k, 2 questions with a maximum score of 10). The APAIS-k component scores were grouped into low (2 to 4), medium (5 to 7) and high (8 to 10) need for information, as in the original APAIS study. Within the APAIS, the items which assess anxiety regarding surgery (APAIS-sur, 3 questions with a maximum score 15) and the items which evaluate anxiety regarding anesthesia (APAIS-an, 3 questions with a maximum score 15) were also analysed separately. To evaluate the extent of knowledge of the patients about their disease, a knowledge test was performed, where the patients were asked to answer ten multiple choice questions about LDH, the upcoming surgery and basic instructions for the postoperative period. In each question, there was only one correct answer and the patients were asked to encircle only one of the answers. It was possible to get a maximum of 10 points, one for each correctly answered question. If a patient encircled two options for one question with one of those being correct, they were given 0,5 points. A wrong answer or all three options encircled gave 0 points.

Postoperative evaluation

A follow-up evaluation was performed 6 months after the operation. The patients were interviewed over the phone. They were asked about daily persisting back or leg pain and an average VAS-p (from 0 to 100) was used to evaluate pain intensity considering the previous two weeks. Furthermore, the patients were asked to rate their global satisfaction with the results of the treatment. The answers were rated as ‘satisfied’, ‘somewhat dissatisfied’ or ‘dissatisfied’ and the patients, who were dissatisfied or somewhat dissatisfied were categorized as dissatisfied for further analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses included descriptive statistics for all measures. All continuous variables were checked for normality using Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Statistical comparisons between groups were performed with Student’s t-test (paired and unpaired). Paired t test was used to compare the pre- and postoperative VAS-p scores as well as APAIS-an and APAIS-sur items. Mann-Whitney U-test was used for comparisons between groups if the data was not normally distributed. Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance was used to compare the APAIS-a data between different APAIS-k groups. Spearman’s correlation analysis was used to evaluate the correlation between the continuous variables. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the differences in proportions. Bonferroni correction was used for post-hoc analysis. Multiple linear regression was performed to analyze the effect of main demographic and clinical variables on the APAIS-total values. Multivariate logistic regression model was built to assess the influence of anxiety scores, clinical and demographic factors on satisfaction with treatment results. The analyses were performed using the JMP software (version 8.0.1, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and GraphPad InStat-3 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

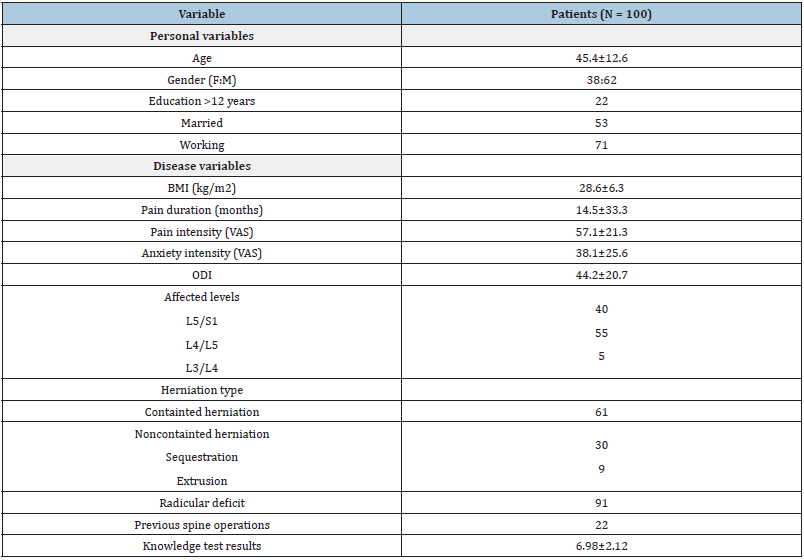

We prospectively collected data on 100 consecutive patients (38% female and 62% male), but 23 patients failed to complete the follow-up evaluation (15 were unreachable and 8 declined to participate), leaving 77 patients for the final analysis. The characteristics of the patients and clinical variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1: Patients characteristics.

VAS visual analog scale, ODI Oswestry Disability Index, BMI body mass index

Anxiety values

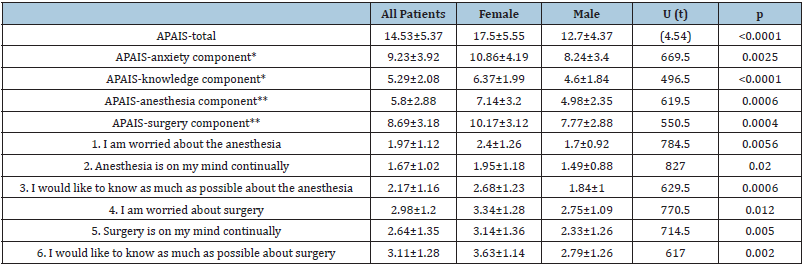

Most of the patients (86%) described preoperative anxiety (VAS-a>0). The APAIS scores of the cases are presented in Table 2. All APAIS scores were significantly higher for surgery than for anesthesia: APAIS total - 8.69±3.18 vs 5.8±2.88 (t=9.82; p<0.0001); APAIS-a - 5.62±2.39 vs 3.66±2.02 (t=8.96; p<0.0001) and APAIS-k - 3.11±1.28 vs 2.17±1.16 (t=7.62; p<0.0001). VAS-a scores were significantly correlated with APAIS-a (r=0.6; p<0.0001), APAIS-k (r=0.29; p-0.0055) and APAIS-total values (r=0.55; p<0.0001).

Determinants of anxiety

VAS-a scores were significantly related to VAS-p results (r=0.32; p=0.0015). Patients with higher pain intensity according to VAS-p scores experienced also higher anxiety according to APAIS-a ( r=0.25; p=0.016), APAIS-k (r=0.24; p=0.025) and APAIS-total (r=0.27; p=0.01) scores. The mean preoperative VAS-a score was significantly higher in females (3.03±2.14 vs 5.07±2.71; U=635; P=0.0004), but there were no significant gender differences in VAS-p scores. Female patients had significantly higher APAIS scores than men (Table 2). Education, age, body mass index (BMI), ODI, history of previous spine operations, marital and employment status were not related to VAS-a or APAIS scores. The relations between VAS-a and the knowledge test results were not significant (r= -0.19; p=0.058), but the patients with higher anxiety according to APAIS-a were less informed about the disease according to the knowledge test (r=-0.21; p=0.037). APAIS-a scores were significantly correlated with APAIS-k (r=0.59; p<0.0001) values. There was a correlation between increasing anxiety level and need for information according to APAIS-k: APAIS-a scores were 8.67±2.83, 10.2±3.5, and 12.1±3.6, respectively, for low, medium, and high APAIS-k scores (p<0.001). However, there was no correlation between the need for information according to APAIS-k and the knowledge test results. The female gender was the only factor that proved to be significantly related to APAIS-total scores in a multivariate analysis (t=2.13; p=0.04).

Table 2: Gender differences of APAIS scores.

Questions1,2,4, and 5 are the anxiety component; questions 3 and 6 are the knowledge component. **Questions1, 2, 3 are the anesthesia component; questions 4, 5, 6 are the surgery component.

Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

APAIS Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale

Relations between anxiety scores and outcome

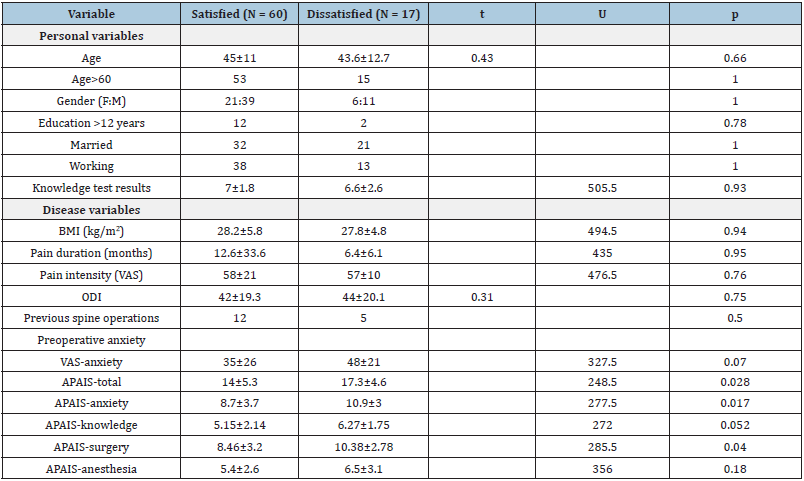

Pre- and postoperative VAS-p results were significantly different (5.7±2 vs 3.6±2.8; t=5.5; p<0.0001). The patients, who were satisfied with the treatment results had significantly lower postoperative VAS-p values (3.1±2.8 vs 4.9±2.3; U=314; p=0.02). We did not find correlation between preoperative anxiety scores and postoperative VAS-p values, however, the patients with higher APAIS-total, APAIS-a and APAIS-sur scores were more frequently not satisfied with the results of the treatment (Table 3). APAIS-total score was the only factor that proved to be significantly related to the dissatisfaction with the treatment results in a multivariate model (χ2= 4.63; p=0.03).

Table 3: Comparison between satisfied and dissatisfied patients after lumbar discectomy (77 patients).

VAS visual analog scale, ODI Oswestry Disability Index, BMI body mass index, APAIS Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale

Discussion

The present study showed that preoperative anxiety is common before LD and female gender is the most important contributor to higher anxiety values. Preoperative anxiety is related to the extent of knowledge about LDH and associated with postoperative dissatisfaction with the treatment results.

In our study, 86% of the patients experienced preoperative anxiety before LD and the APAIS scores were significantly higher for surgery than for anesthesia. Our findings are similar to previous reports about higher anxiety values for surgery than for anesthesia before LD [7], or neurosurgical operations in general [5,6,8]. Aust et al. demonstrated that the magnitude of the difference in surgery and anesthesia anxiety scores depends on the surgical discipline and among the overall differences observed between the surgical disciplines, the largest one was observed in neurosurgical patients [5]. However, despite the relevance of anxiety about surgery, it has to be acknowledged that some patients feel more anxiety about anesthesia.

Female gender was the most important factor contributing to higher levels of all components of anxiety according to APAIS. Our findings reconfirm the earlier reports about the relevance of gender as a risk factor for preoperative anxiety [3,7,8,19]. Eberhart et al. [3] reported that female gender independently predicted all three APAIS anxiety subscales in a cross-sectional survey which enrolled over 3000 patients scheduled to undergo elective surgery [3]. However, worse clincal status may increase anxiety values in females - Maclean et al. [20] found that a number of studies about surgical treatment of lumbar degenerative disease reported worse pre- and postoperative pain, disability and health-related quality of life among females [20]. In our study the pain intensity was associated with anxiety level, but females did not have higher VAS-p scores than male patients.

The patients with higher anxiety had worse knowledge test results and a higher need for information, however, there was no correlation between the patient’s desire for information and the extent of knowledge about LDH. It is well known that two personalities relevant to patients’ pre-surgical education have been differentiated: blunting-like and information-seeking personalities [21]. The blunters have no need for information as they cope with preoperative stress by actively avoiding the threat. The information-seeking personalities, on the contrary, want to know as much as possible and direct their attention towards the stressor. Still, a positive correlation between increasing anxiety level and need for information has been described by several authors [8,18] and there is evidence that enhanced patient education is important to reduce preoperative anxiety [4]. Burgess et al. found limited, but fair-quality evidence that supports the inclusion of a preoperative education session for improving clinical (pain, function, and disability), economic (quality-adjusted life years, healthcare expenditure, direct and indirect costs) and psychological outcomes (anxiety, depression and fear-avoidance beliefs) from spinal surgery [22]. Obviously, the patient’s knowledge about the disease does not have to correlate with the desire for new information, however, according to our data, both these factors can be significant contributors to the development of preoperative anxiety and should be examined separately.

In our study, the patients with higher APAIS-values did not have significantly higher postoperative VAS-p scores but were more frequently not satisfied with the results of the treatment. Associations between preoperative anxiety and chronic postsurgical pain after LD has been described by several authors [9,11,15], however, Hegarty et al. [12] did not find a significant correlation between anxiety and postsurgical pain [12], and Laufenberg- Feldmann et al. [23] did not find evidence for the presence of anxiety before disc surgery as a prognostic factor for ongoing pain and regular postoperative intake of analgesics [23]. Postoperative patient satisfaction has become a central metric for measuring the quality of care after spine surgery and various factors have been suggested as influencing eventual satisfaction, however, it is still not clear why some patients are not satisfied with the treatment results. Ehlers et al. [24] found that more than half of the patients with no improvement or worse outcomes in pain or function after lumbar spine surgery were satisfied with their surgery, which suggested that satisfaction ratings may be based on non-clinical aspects of care [24]. Rönnberg et al. [25] found that patients with preoperative positive expectations on work return and realistic expectations on pain and physical recovery had a greater chance to be satisfied with the surgical results after lumbar disc herniation, as compared to patients with negative and/or unrealistic expectations [25].

Several limitations should be considered in interpreting our findings. First of all, the study focused on analyzing the effect of preoperative anxiety on postoperative satisfaction and clinical outcome, but the psychological status of patients after surgery was not evaluated. Secondly, we have used global assessment of satisfaction with the treatment outcome, which can mask specific dissatisfactions, and utilization of multi-item measures should be recommended. Furthermore, the results may not be generalizable to other surgical populations and other surgical centers. Variations in the anxiety measurement methods may also create certain differences between different studies.

Conclusion

We can conclude that the patients undergoing LD present high levels of preoperative anxiety, especially related to surgery. As anxiety is related to dissatisfaction with treatment results, awareness, and proper preoperative screening are indicated in patients scheduled for LD. Additional preoperative educational information could be important to diminish perioperative anxiety. Further studies should be concentrating on the development of supportive measures and treatment of preoperative anxiety before LD.

References

- Pritchard MJ (2009) Identifying and assessing anxiety in pre-operative patients. Nurs Stand 23: 35-40.

- Hernández PJ, Fuentes GD, Falcón AL, Rodríguez RA, García PC, et al. (2015) Visual analogue scale for anxiety and amsterdam preoperative anxiety scale provide a simple and reliable measurement of preoperative anxiety in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Int Cardiovasc Res J 9: 1-6.

- Eberhart L, Aust H, Schuster M, Sturm T, Gehling M, et al. (2020) Preoperative anxiety in adults - a cross-sectional study on specific fears and risk factors. BMC Psychiatry 20: 140.

- Strøm J, Bjerrum MB, Nielsen CV, Thisted CN, Nielsen TL, et al. (2018) Anxiety and depression in spine surgery-a systematic integrative review. Spine J 18: 1272-1285.

- Aust H, Eberhart L, Sturm T, Schuster M, Nestoriuc Y, et al. (2018) A cross-sectional study on preoperative anxiety in adults. J Psychosom Res 111: 133-139.

- Goebel S, Mehdorn HM (2018) Assessment of preoperative anxiety in neurosurgical patients: Comparison of widely used measures and recommendations for clinic and research. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 172: 62-68.

- Lee JS, Park YM, Ha KY, Cho SW, Bak GH, et al. (2016) Preoperative anxiety about spinal surgery under general anesthesia. Eur Spine J 25: 698-707.

- Perks A, Chakravarti S, Manninen P (2009) Preoperative anxiety in neurosurgical patients. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 21: 127-130.

- Dorow M, Löbner M, Stein J, Konnopka A, Meisel HJ, et al. (2017) Risk factors for postoperative pain intensity in patients undergoing lumbar disc surgery: A Systematic Review. PloS One.

- Junge A, Dvorak J, Ahrens S (1995) Predictors of bad and good outcomes of lumbar disc surgery. A prospective clinical study with recommendations for screening to avoid bad outcomes. Spine 20: 460-468.

- D'Angelo C, Mirijello A, Ferrulli A, Leggio L, Berardi A, et al. (2010) Role of trait anxiety in persistent radicular pain after surgery for lumbar disc herniation: a 1-year longitudinal study. Neurosurgery 67: 265-271.

- Hegarty D, Shorten G (2012) Multivariate prognostic modeling of persistent pain following lumbar discectomy. Pain Physician 15: 421-434.

- Trief PM, Grant W, Fredrickson B (2000) A prospective study of psychological predictors of lumbar surgery outcome. Spine 25: 2616-2621.

- Zieger M, Schwarz R, König HH, Härter M, Riedel-Heller SG (2010) Depression and anxiety in patients undergoing herniated disc surgery: relevant but underresearched - a systematic review. Cent Eur Neurosurg 71: 26-34.

- Theunissen M, Peters ML, Bruce J, Gramke HF, Marcus MA (2012) Preoperative anxiety and catastrophizing: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the association with chronic postsurgical pain. Clin J Pain 28: 819-841.

- Lee J, Kim HS, Shim KD, Park YS (2017) The effect of anxiety, depression, and optimism on postoperative satisfaction and clinical outcomes in lumbar spinal stenosis and degenerative spondylolisthesis patients: Cohort study. Clin Orthop Surg 9: 177-183.

- Fairbank JC, Couper J, Davies JB, O’Brien JP (1980) The oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire. Physiotherapy 66: 271-273.

- Moerman N, van Dam FS, Muller MJ, Oosting H (1996) The Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale (APAIS). Anesth Analg 82: 445-451.

- Celik F, Edipoglu IS (2018) Evaluation of preoperative anxiety and fear of anesthesia using APAIS score. Eur J Med Res 23: 41.

- MacLean MA, Touchette CJ, Han JH, Christie SD, Pickett GE (2020) Gender differences in the surgical management of lumbar degenerative disease: a scoping review. J Neurosurg Spine 31: 1-18.

- Miller SM, Mangan CE (1983) Interacting effects of information and coping style in adapting to gynecologic stress: should the doctor tell all? J Pers Soc Psychol 45: 223-236.

- Burgess LC, Arundel J, Wainwright TW (2019) The effect of preoperative education on psychological, clinical and economic outcomes in elective spinal surgery: A systematic review. Healthcare (Basel) 7(1): 48.

- Laufenberg FR, Kappis B, Cámara RJA, Ferner M (2018) Anxiety and its predictive value for pain and regular analgesic intake after lumbar disc surgery - a prospective observational longitudinal study. BMC Psychiatry 18(1): 82.

- Ehlers AP, Khor S, Cizik AM, Leveque JA, Shonnard NS, et al. (2017) Use of patient-reported outcomes and satisfaction for quality assessments. Am J Manag Care 23(10): 618-622.

- Rönnberg K, Lind B, Zoëga B, Halldin K, Gellerstedt M, Brisby H (2007) Patients' satisfaction with provided care/information and expectations on clinical outcome after lumbar disc herniation surgery. Spine 32: 256-261.

© 2022 Tõnu Rätsep. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)