- Submissions

Full Text

Orthopedic Research Online Journal

Ulnar Collateral Ligament Reconstruction: Allograft Versus Autograft – A Systematic Review

Austin Moore DO1, Dylan Matthews DO1, Julie Stausmire2, Amy Singleton BS1*, Kirk Davis DO1 and Anil Gupta MD3

1Department of Orthopedics, Mercy Health St Vincent Medical Center, 2409 Cherry Street, USA

2Regional Academic Affairs, Mercy Health St Vincent Medical Center, 2215 Cheery Street, USA

3Toledo Orthopedic Surgeons, 2865 N Reynolds Rd, USA

*Corresponding author:Amy Singleton BS, Department of Orthopedics, Mercy Health St Vincent Medical Center, 2409 Cherry Street, USA

Submission: August 16, 2021;Published: August 31, 2021

ISSN: 2576-8875 Volume8 Issue4

Abstract

Background: Ulnar Collateral Ligament (UCL) reconstruction of the elbow, a Tommy John surgery, is a common procedure often performed in throwing athletes. Autograft tendon has traditionally been utilized, although recently allograft tendon has been of interest due to the possibility of decreasing donor site morbidity. There is a lack of literature on patient outcomes and complication rates following the use of allograft tendon for UCL reconstruction. Currently, there is no consensus on utilizing autograft versus allograft tendon for UCL reconstruction.

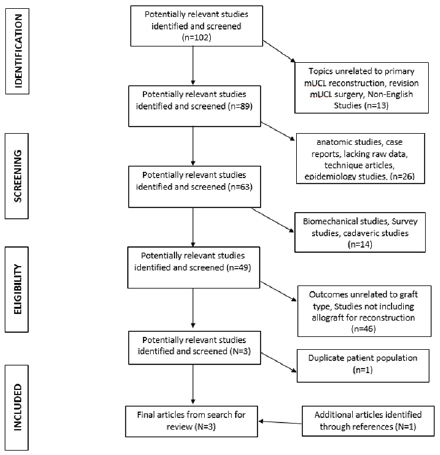

Methods: A PRISMA compliant literature search in online databases Medline, Cochrane and Embase was performed for level 4 and higher studies through June 2019. Any studies reporting clinical outcome results of allograft reconstruction were included. Exclusion criteria included studies unrelated to primary UCL reconstruction, studies specifically looking at revision UCL reconstruction, epidemiological studies, case reports, studies lacking raw data, technique articles, biomechanical studies, cadaveric studies, studies with outcomes unrelated to graft choice, and studies with outcomes unrelated to the use of allograft tendon for reconstruction. Studies were analyzed for graft type, functional scores, return to play rate, and complication rates.

Results: Three out of 103 studies met inclusion criteria. Two cohort studies and 1 retrospective review were included in this review. No significant differences in functional outcomes regardless of scoring system utilized, return to play rate, or complication rates were found between allograft versus autograft.

Conclusion: The use of allograft tendon appears to have similar outcomes regarding functional scores, return to play, and complication rates compared to autograft tendon. Use of allograft tendon seems to be a viable option for UCL reconstruction, though further studies are needed.

Keywords: Allografts; Autografts; Elbow; Ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction; Tommy john; Elbow instability

Abbreviations: UCL: Ulnar Collateral Ligament; PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; KJOC: Kerlan-Jobe Orthopaedic Clinic Shoulder and Elbow Scores; MEPS: Mayo Elbow Performance Scores; OES: Oxford Elbow Scores; DASH: Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand Scores

Introduction

Injury to the medial Ulnar Collateral Ligament (UCL) was originally described by Waris [1] in 1946 in Javelin throwers. Today, baseball pitchers are an increasingly common demographic who sustain injuries to the UCL [2]. Commonly, UCL injuries in pitchers are overuse injuries due to the repetitive valgus force applied during the acceleration phase of throwing [2]. Throwing athletes with acute UCL injuries may describe a pop associated with pain and difficulty with throwing. They often have pain during the late cocking and early acceleration phases of throwing. This leads to decreased velocity and accuracy with throwing [3]. UCL injuries are not only limited to the throwing athletes; injury can also occur during any activities that cause repetitive valgus moments on the elbow. Traumatic elbow dislocation can also lead to acute UCL injury. On physical exam, the most common

finding is tenderness to palpation over the medial elbow at the UCL

origin. Patients may or may not report having pain at rest, and many

chronic tears are symptomatic only during a throwing motion [2].

The medial UCL is the primary restraint to valgus stress on the

elbow, and anatomically is divided into 3 components, the anterior

bundle, posterior oblique ligament, and transverse ligament [4].

In the anterior bundle, the anterior oblique ligament originates at

the anteroinferior ridge of the medial epicondyle to the sublime

tubercle, and along its course subdivides into anterior and posterior

bands of which the anterior band is the primary valgus restraint

[5]. The anterior band of the anterior bundle is the primarily

stabilizer from 30 to 120 degrees of flexion while the posterior

band has the same function at terminal phase of elbow flexion

[6]. The transverse ligament does not contribute to stability of the

elbow. During the late cocking and acceleration phases of throwing,

a significant valgus stress is placed on the elbow, which leads to

repetitive micro-trauma to the anterior band of the UCL, which can

eventually lead to rupture.

In 1974, Jobe et al. [7] performed the first successful medial

ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction on baseball pitcher Tommy

John, leading to the procedure’s moniker. Later on, in 1986, Jobe

et al. [7] described a technique for reconstruction of the ligament

with use of ipsilateral palmaris longus tendon autograft via flexor

pronator mass detachment with transposition of ulnar nerve.

Since then, there have been several modifications and variations

of Dr. Jobe’s original technique. There have also been an increasing

number of tendon graft origins for UCL reconstruction that have

been utilized including palmaris, hamstring, plantaris, and Achilles

autograft. Unfortunately, with autograft harvest, there can be

complications involving the graft site including graft site pain,

infection, numbness, and even incidental harvesting of the median

nerve. With recent improved tissue processing techniques, allograft

has become a viable treatment option to avoid donor site morbidity.

To date, there has been a paucity of literature surrounding

outcomes following UCL reconstruction with allograft. The purpose

of this study is to evaluate outcomes after UCL reconstruction with

allograft versus with autograft tendons in regard to functional

scores, return to play rate, and complication rates.

Methods

A systematic review was first registered on Prospero and a

literature search was performed using Preferred Reporting Items

for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines

(Figure 1); [8,9]. The search was performed utilizing Medline,

Cochrane, and Embase electronic databases, first in March and

then in June 2019 to identify the most contemporary articles.

Full text versions of articles were reviewed by two independent

resident physician reviewers. Primary search terms included: ulnar

collateral ligament reconstruction, allograft, autograft, Tommy

John, reconstructive surgical procedures, and surgical repair used

in combination and/or independently.

Inclusion criteria were defined as any studies reporting clinical

outcome results of allograft reconstruction. Exclusion criteria for

studies were studies in a non-English language, studies unrelated to

primary medial UCL reconstruction, studies specifically looking at

revision medial UCL reconstruction, epidemiological studies, case

reports, studies lacking raw data, technique articles, biomechanical

studies, cadaveric studies, studies with outcomes unrelated to graft

choice, and studies with outcomes unrelated to the use of allograft

tendon for reconstruction.

Studies with levels of evidence of 4 or higher were included

and then reviewed for identical patient populations. Two studies

by Erickson et alwere identified which included the same patient

population [10,11]. The study with the higher level of evidence

between these two studies was included in our review. The

references of our included studies were then cross examined for

any additional studies which could be included, resulting in one

additional study. Studies identified were then reviewed for graft

type used and various functional outcomes, return to play, and

complications

Figure 1: PRISMA Flowsheet for study inclusion.

Results

Out of 103 studies initially identified in our literature search, 3

met all inclusion criteria. Two studies were level 3 cohort studies,

and one study was a level 4 retrospective review. Of the studies

identified, no significant differences were found between functional

outcome scores, return to play, or return to play at previous level of

competition.

In Erickson et al. [11] a level 3 cohort study, 85 patients between

2004-2013 underwent UCL reconstruction. 11 patients underwent

reconstruction with allograft tendon, 20 underwent reconstruction

with hamstring autograft tendon, and 54 underwent reconstruction

with palmaris autograft tendon. Functional outcomes scores were

reported using the Kerlan-Jobe Orthopaedic Clinic Shoulder and

Elbow Score (KJOC) and the Timmerman-Andrews Score. KJOC

scores for palmaris autograft, hamstring autograft, and allograft

were 91.67±8.59, 89.62±9.12, and 91.66±3.20 respectively

(p=0.251). Timmerman-Andrews Score between the palmaris

autograft, hamstring autograft, and allograft were 91.67±8.59,

93.75±5.82, and 94.55±4.72 respectively (p=0.181). Percentage

of patients who returned to play at the same level or higher as

preinjury was 92.59 % for palmaris autograft, 95% for hamstring

autograft, and 100% for allograft reconstruction (p=0.999). No

difference in complications between the type of graft used was

identified. Complications included reoperation for ulnar nerve

transposition (n=6), ulnar stress fracture (n=1), loss of motion

requiring reoperation with elbow arthroscopy (n=1), and one UCL

re-tear, ultimately treated non-operatively.

Merolla’s et al. [12] study included 15 patients who

underwent UCL reconstruction between 2006-2012. Of the 15

patients, 5 underwent reconstruction with palmaris autograft

and 10 underwent reconstruction with semitendinosus allograft.

Functional outcome scores were reported using the Mayo

Elbow Performance Score (MEPS), Oxford Elbow Score (OES),

and Disabilities of the Arm Shoulder and Hand score (DASH).

Overall MEPS scores improved from 56.3 preoperatively to 93.8

postoperatively, OES from 23.9 to 45.8, and DASH from 31.8 to 1.81.

This study reported improvement in post-operative functional

scores in each scoring system, though there were no significant

difference noted between any of the above outcome scores between

autograft and allograft groups (p>0.05). This study did not report

complication rates, though they did identify calcific deposition in all

grafts, 10 at the humeral insertion and 5 at the ulnar insertion. They

did not report on return to play rates.

A retrospective study by Savoie et al. [8] evaluated functional

outcome scores, return to play rate, range of motion, and

complications at 2 years in 116 patients who underwent ulnar

collateral ligament reconstruction with allograft tendon. Of the

116 patients, gracilis allograft was used in 100 patients, and

semitendinosus allograft was used in 16 patients. Functional

outcome scores were reported with the Conway-Jobe scale. 93

patients reported excellent outcomes (81%), 15 patients reported

good outcomes (13%), 8 patients reported fair outcomes (7%), and

no patient reported poor outcomes. 33 patients (28.4%) returned

to play above preinjury level, 64 (55.1%) returned at preinjury

level, 13 (11.2%) returned below preinjury level, and 6 (5.2%)

did not return to play, 3 of which were for reasons unrelated to

their surgery. Average return to competition was 9.5 months.

Postoperative complications, reported in 7 patients (6%), included

1 ulnar neuropathy, 2 late sensory neuropathy, 2 postoperative

wound issues, 1 medial humeral epicondyle fracture, and 1 flexorpronator

muscle and tendon tear. No graft failures were reported.

Savoie et al concluded that outcomes following reconstruction

with allograft versus autograft were similar in regard to Conway-

Jobe outcome scores, return to play rate, range of motion, and

complication rates.

Discussion

Ulnar collateral ligament tears occur most often in pitchers

and other overhead throwing athletes resulting in instability of the

elbow joint [10]. Reconstruction of the UCL with autograft tendon

has been a mainstay in treatment since the late 1900’s. Although

successful as a treatment for returning elbow stability, the use of

autograft also provides the potential opportunity for donor site

morbidity as well as extended operating room time. Donor site

morbidity ranges from minor symptoms such as donor site pain and numbness, to severe complications, including infection and

damage to surrounding structures. Numbness in the infrapatellar

branch of the saphenous nerve distribution has been reported in

up to 88% of patients who underwent hamstring autograft harvest

[13]. A more severe and detrimental complication of incidental

harvest of the median nerve has also been reported with palmaris

longus tendon autograft harvest [14]. The use of allograft tendon

for UCL reconstruction appears to be an appropriate alternative

for reducing these potential complications that can be seen with

autograft harvesting.

Functional outcomes after UCL injury and surgical repair are

of great interest due to injury often occurring in the workplace. In

previous papers, UCL reconstruction with autograft has resulted in

favorable functional scores and patient satisfaction [1]. In reviewing

the articles discussed here, improvement and good to excellent

functional scores were reported in all patient cohorts regardless of

the score system utilized. The use of allograft versus autograft does

not seem to significantly impact functional outcome, but further

large-scale studies are needed to identify subtle differences in

function.

As UCL injury occurs often in athletes, return to play rates

are of particular interest. Previously published studies on UCL

reconstruction demonstrate favorable return to play rates. In

2015, Erickson et al. [10] performed a systematic review reporting

on return to play rates and functional outcome scores of patients

undergoing UCL. Twenty studies were included reviewing 2,019

elbows that underwent UCL reconstruction. They found an overall

return to play rate at 86.2%. A study by Marshal et al. [3] evaluated 46

major league baseball pitchers who underwent UCL reconstruction

with the use of gracilis or palmaris autograft tendons and did not

determine any significant difference in performance outcomes

between the two patient cohorts [4]. They found an overall return

to play rate of 96%, with 82% returning to play at the previous

MLB level. A larger systematic review and meta-analysis by Peters

et al. [15] found an overall return to play of 90% among all patients

who underwent UCL reconstruction. Interestingly, based on level

of expertise, 78% of Major League Baseball players, 67% of Minor

League Baseball Players, 92% of collegiate players, and 83% of

high school players returned to previous level of play. Erickson et al

reported similar levels of return to play as found in these previous

studies, and also found that 100% of patients who underwent UCL

reconstruction with allograft returned to play at the same level or

higher, although there was no significant difference found due to

the high return to play rate in both groups, and the small population

size [11]. Savoie et al. [8] also demonstrated a high return to play

rate of 83.5% at or above previous level of play. Overall, there is

a high return to play rate utilizing either autograft or allograft for

UCL reconstruction, and further studies are needed to demonstrate

a significant difference.

As with any surgical procedure, identifying and minimizing

postoperative complications is imperative to improving patient

outcomes. Complications following UCL reconstruction have been

reported in as high as 10.4% of patients and include in decreasing

incidence: ulnar neuritis (77%), donor site issues (12.5%), need for

revision UCLR (6.6%), stiffness (2.8%), reactive synovitis (1.4%),

post-operative hematoma (0.9%), ulnar tunnel fracture (0.9%) [10].

A meta-regression and systematic review performed by Somerson

et al. [16] demonstrated a similar overall complication rate of

10.2% with the primary complications being ulnar neurapraxia

developing in 6.7% of all patients. Of interest, they found patients

were more likely to report excellent or good Conway outcome

rating if they did not report an ulnar neurapraxia, demonstrating

that neurapraxia is subjectively related to how patients perceive

their functional outcome. Erickson et al. [11] found that while

there were no differences in complications between the type of

graft used, more complications were identified with the standard

docking technique that the double-docking technique. Interestingly,

allografts were used more often with the double-docking technique,

while hamstring autograft were used primarily with the standard

docking technique. In Savoie et al, the rate of complications was

reported as 6%, though this is a single study and may be the result

of a small patient cohort.8 Further studies with equal technique

distribution and reporting methods are needed to determine if

there is a difference in complication rate and type between allograft

and autograft.

The studies identified by our literature search appear to

demonstrate comparable functional outcomes, return to play rate,

and complication rates with the use of allograft tendon versus

autograft tendon in UCL reconstruction. The main limitation of our

study was the availability of very few comparative studies directly

evaluating autograft versus allograft use in UCL reconstruction.

Those that do exist consist of very small patient cohorts which

limits the possibility of statistical analysis. While there appear

to be trends toward similar, and favorable, outcomes between

the two graft options, the heterogeneity of the studies limit data

extrapolation. Additionally, the studies reviewed were retrospective

in nature, and prospective double-blind control studies are needed

for more substantial data. While these limitations exist, there

appear to be similar outcomes between graft types, and we feel

allograft reconstruction is an appropriate treatment option for UCL

reconstruction.

Conclusion

While there is a paucity of comparative literature regarding the use of allograft versus autograft tendon in UCL reconstruction, there does not appear to be any significant difference in regards to functional scores, return to play rate, or complication rates. Further study into this topic is needed to determine more adequate reliability of our conclusions, although from the available literature it does appear to be an appropriate option while sparing potential complications of donor site morbidity. Overall, allograft reconstruction is an adequate option for ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction.

References

- Waris W (1946) Elbow injuries of javelin-throwers. Acta Chir Scand 93(6): 563-575.

- Petty DH, Andrews JR, Fleisig GS, Cain EL (2004) Ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in high school baseball players: clinical results and injury risk factors. Am J Sports Med 32(5): 1158-1164.

- Marshal N, Keller R, Orr L (2019) Major league baseball pitching performance after Tommy John surgery and the effect of tear characteristics, technique, and graft type. Am J Sports Med 47(3): 713-720.

- Regan WD, Korinek SL, Morrey BF, An KN (1991) Biomechanical study of ligaments around the elbow joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res (271): 170-179.

- Molenaars R, Bekerom M, Eygendaal D (2019) The pathoanatomy of the anterior bundle of the medial ulnar collaterallLigament. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 28: 1497-1504.

- Morrey BF, An KN (1983) Articular and ligamentous contributions to the stability of the elbow joint. Am J Sports Med 11(5): 315-319.

- Jobe F, Stark H, Lombardo S (1986) Reconstruction of the ulnar collateral ligament in athletes. J Bone Joint Surg Am 68(8): 1158-1163.

- Savoie F, Morgan C, Yaste J, Hurt J (2013) Medial ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction using hamstring allograft in overhead throwing athletes. J Bone Joint Surg Am 95(12): 1062-1066.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tezlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyzes: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339: b2535.

- Erickson B, Chalmers P, Bush-Joseph C (2015) Ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction of the elbow: A systematic review of the literature. Orthop J Sports Med 3(12): 2325967115618914.

- Erickson B, Cvetanovich G, Frank R (2016) Do clinical results and return-to-sport rates after ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction differ based on graft choice and surgical technique. Orthop J Sports Med 4(11): 2325967116670142.

- Merolla G, Del Sordo S, Paladini P, Porcellini G (2014) Elbow ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction: Clinical, radiographic, and ultrasound outcomes at a mean 3- year follow up. Musculoskelet Surg 98 Suppl 1: 87-93.

- Hardy A, Casabianca L, Andrieu K (2017) Complications following harvesting of patellar tendon or hamstring tendon grafts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: Systematic review of literature. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 103(8S): S245-S248.

- Leslie B, Osterman A, Wolfe S (2017) Inadvertent harvest of the median nerve instead of the palmaris longus tendon. J Bone Joint Surg Am 99(14): 1173-1182.

- Peters S, Bullock G, Goode A (2018) The success of return to sport after ulnar collateral ligament injury in baseball: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 27(3): 561-571.

- Somerson J, Petersen J, Neradilek M (2018) Complications and outcomes after medial ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction: A meta-regression and systematic review. JBJS Rev 6(5): e4.

© 2021 Amy Singleton BS. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)