- Submissions

Full Text

Orthopedic Research Online Journal

A Late Presenting Tuberculous Dactylitis Case: Choosing the First Line Medical Treatment or going Ahead with Surgical Debridement?

Ramin Zargarbashi1, Ehsan Mahmoudi2, Kamand Khalaj3, Alireza Nezami2*, Nesa Milan4

1Assistant Professor at Orthopedic Department, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Iran

2Orthopedic Resident, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Iran

3Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Iran

4Research Assistant at Center of Orthopedic Trans-Disciplinary Applied Research (COTAR), Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Iran

*Corresponding author:Alireza Nezami, Orthopedic Resident, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Iran

Submission: April 27, 2021;Published: May 12, 2021

ISSN: 2576-8875 Volume8 Issue2

Abstract

Background: Metacarpals and phalanges are rarely affected in extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Tuberculous dactilytis is defined as infection of metacarpals, metatarsals, and phalanges of hands and feet in tuberculosis patients. About 85% of affected people with tubercular dactylitis are younger than 6 years old. As a result of the structure difference between pediatric and adult hand, the disease manifestation and the subsequent course differ substantially.

Case presentation: A 5-year-old female with isolated metacarpal bone involvement admitted to Children medical center Hospital, Tehran ,Iran. The patient history indicated a 6 months antibiotic therapy with no improvement. Based on radiological and sonographical evidences, a surgical intervention was implemented to remove the necrotic tissues and promote vascularization. The patient was discharged and prescribed Ethambutol/isoniazid/pyrazinamide/rifampicin and Vitamin B6 for six months.

Conclusion: The surgical debridement can be suggested as a first line treatment for TB dactilytis, when the bone is severely damaged. In such cases antibiotic therapy should be administered after the surgery.

Keywords: Tuberculous; Dactilytis; Infection; Bone; Debridement; Microbiology; Palliative care

Introduction

Skeletal Tuberculosis (TB) represents only 1%–5% of all tuberculous infections [1]. The bones of the hands are more affected than the bones of the feet. This disorder is described as “spina ventosa” because of its radiographic features of cystic expansion of the involved short tubular bones [2]. Tuberculous dactylitis describes the tubercular involvement of phalanges of the hands or feet. However, various authors have extended its use to describe synovitis with or without finger/toe bone involvement, joint infection, and even involvement of metacarpals [3]. Overall, the tubercular dactylitis represents 2-4% of osteoarticular TB [4].

Tuberculous dactylitis mainly arises from the lymphohematogenous dissemination. The lung is the primary hub in 75% of cases [2]. In tubular bones, the hematopoietic marrow is more prone to TB infection , resulting in generation of granulation tissue, fusiform swelling of the affected area, cortical thinning and development of radiolucent marrow space. The final outcomes include cortical destruction and painless swelling of a finger with a few months’ duration. As opposed to acute osteomyelitis , the disease often represents a benign course with no sign of pyrexia or acute inflammation. A low-grade fever and pain at the infected site as well as sinus formation may also be detected. Anorexia and weight loss are considered as common clinical manifestations [5].The most common sites of infection include proximal phalanx of the index and the middle fingers as well as the metacarpals of the middle and ring fingers. Such dactylitis manifests mostly by soft tissue swelling and periostitis. Children aged 6 years and below account for 85% of cases [5,6].

The child’s bones are more porous with higher vascularization compared to adult’s. As a result of rich blood supply, the child’s hand predisposes to the landing of infection into the osseous tissue with involvement of multiple fingers [7]. If the epiphysis invaded, the shortening and deformity of bone is highly expected [3]. The gold standard for the diagnosis of osseous tuberculosis is a positive culture of mycobacterium tuberculosis from bone tissue. Tuberculous dactylitis responds well to anti-TB drugs [8]. However, upon the destruction of bone and lack of response to antibiotic therapy, the surgical treatment is recommended.

Case Presentation

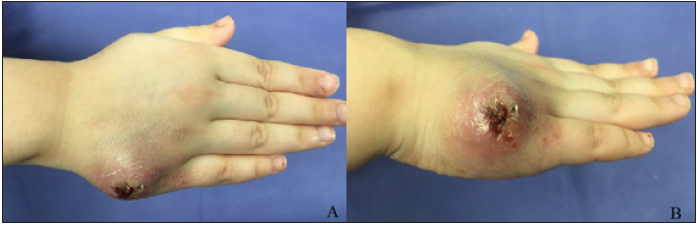

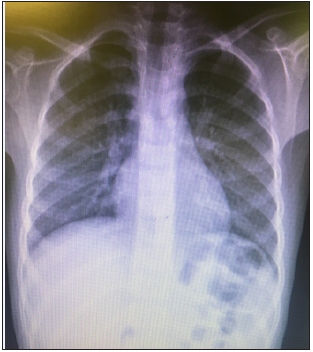

A 5-year-old female was referred to Children medical center Hospital with complaints of progressive enlargement and swelling of the right hand fifth metacarpal bone over two months. She also had weight loss and low-grade fever. She was treated with oral antibacterial drugs, but no improvement was seen. On physical examination, her vital signs were normal. In local examination of the affected area, a 3*4cm spindle-shaped swelling with skin inflammation on the ulnar side of the fifth metacarpal bone was observed (Figure 1). Furthermore, in physical examination a firm, painless lesion, with mild tenderness and discharge was also detected. The result of complete blood count was as below: WBC, 12400 with 81% neutrohpils; hematoctrit 36.3 and the platelet count of 255000. The Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) was 13mm/hr and the Mantoux test showed an 18mm induration. The chest X-Ray confirmed the intact lung parenchymal tissue (Figure 2). Also, the Right-hand X-Ray revealed an osteolytic cyst-like lesion of the 5th metacarpal bone with fusiform soft tissue swelling (Figure 3). Sonographic examination showed hypoechoic pattern and increase of vascularization in peripheral soft tissue that was connected to metacarpal bone via a tract. As a result of delayed referral of the patient, the bone and soft tissues were severely damaged. In this sense, we consulted an infectious specialist, and the surgical procedure was considered.

Figure 1: Spindle shape swelling on the ulnar side of the right hand.

Figure 2: Chest X-Ray without parenchymal pathology.

Figure 3: AP View of right-hand showing bone expansion of the fifth metacarpal.

Considering the size of the lesion and the presence of sinus tract as well as discharge, the surgical intervention was followed. To remove the affected tissues a fish mouth incision on the ulnar side of the right hand was made (Figure 4). Then, subcutaneous and granulation tissues were debrided until the extensor tendons became visible. Following the complete removal of soft tissue and pulling aside the extensor tendon, the sinus tract was seen (Figure 5).

Figure 4: Fish mouth incision around the lesion.

Figure 5: Soft tissue debridement and sinus tract.

The necrotic tissue and pus inside the metacarpal bone were removed through the sinus perforation hole and then the fifth metacarpal bone was completely curettaged (Figure 6). After complete debridement and rinsing the area , the skin was closed. Specimens from soft tissue exudate and metacarpal bone were sent for microbiological and pathological examinations (Figure 7). The result was negative for acid fast staining but positive for TB culture. Pathological smears confirmed necrotizing granulomatous inflammation. Our patient is currently being treated with anti-tuberculosis drug and the metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal Range of motion is shown in (Figure 8).

Figure 6: Metacarpal bone after curettage.

Figure 7: Sample of Soft tissue and metacarpal bone.

Figure 8: Hand joint range of motion 3 months after surgery.

Discussion

Chronic metacarpal or finger swelling in children can be considered as a symptom of tuberculosis. This could be a serious concern in endemic areas. In the present report, our patient was an immigrant from endemic area which is a high-incidence country. This may explain the occurrence of such type of rare TB infection in this patient. Furthermore, certain symptoms such as weight loss and mild fever may increase the possibility of tuberculosis. Based on Hardy and Hartmann’s report, the main symptom of tuberculous dactylitis was painless swelling of fingers followed by sinus formation [9]. Similarly, Leung described painless or mildly painful swelling, as the major presenting symptom [10]. In our study, the patient showed a painless-swelled lesion which is consistent with aforementioned studies.

The skeletal tuberculosis should be differentially diagnosed from pyogenic osteomyelitis, Brodie’s abscess, Kaposi’s sarcoma, and luetic dactylitis. Pyogenic osteomyelitis is supposed to be severely painful, swollen, and warm accompanying fever but tuberculous osteomyelitis is somehow benign with moderate pain and low-grade fever [11]. The low-grade fever was also detected in our case, indicating the possibility of tuberculous osteomyelitis. Tuberculous dactylitis is difficult to diagnose, especially during the early stages, and should be considered when a longstanding pain and swelling in the metacarpals and phalanges is present [11,12]. Tuberculous dactylitis is diagnosed based on radiographic features and Mycobacterium Tuberculosis cultivation. In radiological investigations, the affected bone shows expansion with lytic lesions in the middle and subperiosteal new bone formation along the involved bone. The cavity may contain soft coke sequestrum [12,13]. Additional findings such as osteopenia, soft tissue swelling with minimal periosteal reaction, cysts in the bone adjacent to the joint, and subchondral erosions were also reported. In our represented case, an osteolytic cyst-like lesion of the 5th metacarpal bone with fusiform soft tissue swelling was detected in radiologic imaging.

Metacarpal and phalanges tuberculosis occurs secondary to a primary foci which can be in the respiratory, renal, or GI tract. The lungs are the primary site of infection in approximately 75% of cases [14]. However, in a study by Subasi et al, on seven cases of metacarpal and phalangeal tuberculosis, no patient had an active tuberculous lesion or history of pulmonary disease [15]. Consistent with the Subasi’s report, we did not detect any abnormality in the lung of our patient.

The result of AFB staining was negative in our study, Similar negative results are being reported in AFB staining as the osseous tuberculosis is a paucibacillary lesion [16]. Here we used bacterial culture as the gold standard for diagnosis [12] and the result was positive, indicating microbial invasion to the bone. The treatment of osseous tuberculosis includes a 2-month initial phase of isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol followed by a 6-12 month regimen of isoniazid and rifampicin [17].

Regarding the treatment, those patients who do not respond to 4 or 5 months of chemotherapy, should undergo the surgical debridement. It is noteworthy to mention that antibiotic administration before the surgery can prevent bone destruction and dissemination of disease [18]. In our case, as the patient was referred to our hospital with a long delay, the bone and its associated soft tissues were damaged and after consultation with infectious specialist, the surgery was performed. A similar situation can be found in severe osteomyelitis with abscess formation, where the surgical removal of abscess would be carried out before appropriate chemotherapy [19].

A prolonged course of anti-TB drugs is the basis of treatment. The optimal duration of the treatment has been an issue of considerable debate [15]. Watts and Life so recommended that treatment should be continued for a minimum of 12 months for osteoarticular involvement [20]. In this case, the patient is treated with rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, ethambutol hydrochloride and vit B6 for 6 months after surgery.

Conclusion

In severe tubercular dactylitis, when the bone structure is heavily damaged, the antibiotic treatment is not effective, and the surgical debridement can be introduced as the first line treatment. This surgical procedure may stimulate angiogenesis which in turn, facilitates antibiotic delivery to the area.

References

- Sahli H, Roueched L, Sbai MA, Bachali A, Tekaya R (2017) The epidemiology of tuberculous dactylitis: A case report and review of literature. Int J Mycobacteriol 6(4): 333-335.

- Abebe W, Abebe B, Molla K, Alemayehu T (2016) Tuberculous dactylitis: An uncommon presentation of skeletal tuberculosis. Ethiop J Health Sci 26(3): 301-303.

- Pearlman HS, Warren RF (1961) Tuberculous dactylitis. Am J Surg 101: 769-771.

- Ben Brahim E, Abdelmoula S, Ben Salah B, Kilani F, Chatti Dey S (2003) Digital tuberculous revealed by trauma. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot 89(1): 71-74.

- Singhal A, Arbart A, Lanjewar A, Ranjan R (2005) Tuberculous dactylitis: A rare manifestation of adult skeletal tuberculosis. Indian J Tuberc 52(4): 218-219.

- Andronikou S, Smith B (2002) "Spina ventosa"-tuberculous dactylitis. Arch Dis Child 86(3): 206.

- Patel MR, Malaviya GN, Sugar AM (2005) Green’s operative hand surgery. (7th edn), Elsevier Churchill Livingstone.

- WHO (2014) Guidance for national tuberculosis programmes on the management of tuberculosis in children. World Health Organization, P. 125.

- Hardy JB, Hartmann JR (1947) Tuberculous dactylitis in childhood; a prognosis. J Pediatr 30(2): 146-156.

- Leung PC (1978) Tuberculosis of the hand. Hand 10(3): 285-291.

- Kushwaha RA, Kant S, Verma SK, Sanjay, Mehra S (2008) Isolated metacarpal bone tuberculosis-a case report. Lung India 25(1): 17-19.

- Versfeld GA, Solomon A (1982) A diagnostic approach to tuberculosis of bones and joints. J Bone Joint Surg Br 64(4): 446-449.

- Weaver P, Lifeso RM (1984) The radiological diagnosis of tuberculosis of the adult spine. Skeletal Radiol 12(3): 178-186.

- Kothari PR, Shankar G, Gupta A, Jiwane A, Kulkarni B (2004) Disseminated spina ventosa. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci 46(4): 295-296.

- Subasi M, Bukte Y, Kapukaya A, Gurkan F (2004) Tuberculosis of the metacarpals and phalanges of the hand. Ann Plast Surg 53(5): 469-472.

- Agarwal S, Caplivski D, Bottone EJ (2005) Disseminated tuberculosis presenting with finger swelling in a patient with tuberculous osteomyelitis: A case report. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 4: 18.

- WHO (2003) Treatment of tuberculosis. (4th edn), Pp. 1-147.

- Tuli SM (2004) Tuberculosis of the skeletal system: Bones, joints, spine, and bursal sheaths. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers, New Delhi, India.

- Rao N, Ziran BH, Lipsky BA (2011) Treating osteomyelitis: Antibiotics and surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg 127(Suppl 1): 177s-187s.

- Watts HG, Lifeso RM (1996) Tuberculosis of bones and joints. J Bone Joint Surg Am 78(2): 288-298.

© 2021 Alireza Nezami. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)