- Submissions

Full Text

Orthopedic Research Online Journal

Therapeutic Effects of Endurance Training of Extensors with Core Stabilization Exercise versus Core Stabilization Exercise in the Management of Mechanical Low Back Pain

Karthikeyan T*

Physiotherapist, NIMHANS, India

*Corresponding author: Karthikeyan T, Physiotherapist, NIMHANS, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

Submission: April 20, 2020;Published: June 30, 2020

ISSN: 2576-8875 Volume7 Issue3

Abstract

Mechanical back pain is the general term that refers to any type of back pain caused by placing abnormal stress and strain on muscles of the vertebral column. Typically, mechanical back pain results from bad habits, such as poor posture, poorly designed seating, incorrect bending and lifting motion. The Objectives of the studies are to assess the effect of endurance training of extensors with core stability exercise versus core stability exercise in the management of mechanical low back pain, in terms of pain perception. The second to assess the effect of endurance training of extensors with core stability exercise versus core stability exercise in the management of mechanical low back pain, in terms of functional disability. The methodology which consists of thirty samples selected from the population divided into two equal groups. The procedure was explained to subject. Both the group underwent a pretest measurement of pain intensity and functional disability. Group A treated with endurance training of extensors with core stability exercise. Group B treated with core stability exercise. Hence both groups are treated and after 3 weeks measured pain by visual analogue scale and Functional Disability will be measured using Modified Oswestry Low back pain Disability. The pre and post test values were assessed by VAS and ODI in Group A. The mean difference value is 3 and 4 respectively. The standard deviation value is 1 and0.67 respectively. The pre and post test values were assessed by VAS and ODI in group B. The mean difference value is 16 and 26 respectively. The standard deviation value is 1.26 and 1.45 respectively. The present study which concludes that the endurance training of extensors with core stabilization exercise resulted in a positive impact on their functional activities. The VAS and ODI differences in Mechanical low back pain patients before and after treatment were statistically significant.

Introduction

Mechanical back pain is the general term that refers to any type of back pain caused by placing abnormal stress and strain on muscles of the vertebral column [1]. Typically, mechanical back pain results from bad habits, such as poor posture, poorly designed seating, incorrect bending and lifting motion [2].

Mechanical low back pain is essentially a universal and self limiting phenomenon. It continues to be one of the enigmas of modern medicine [3]. It is not only a medical problem, but a social, legal and practical one as well. Men and women are equally affected [4]. It occurs most often between ages 30 and 50. The natural history of Mechanical low back pain depends upon the influence of age, injury and adaptive changes to the different neuro musculo skeletal changes [5].

Mechanical low back pain otherwise named as “Activity related spinal pain”. It is a common musculo skeletal disorder causing back pain mostly in lower thoracic and lumbar region, it can be either acute or chronic in its clinical presentation [6].

Muscle is a potential source of low back pain. Some authors stated that failure of muscles to protect passive structures from excessive loading may result in damage to the pain sensitive structures in back and produce pain [7]. Lack of endurance of trunk muscles has been identified as a predictor of first-time occurrence of low back trouble [8].

Physical therapy includes patient education and a variety of stretching and strengthening exercises, Manual therapies and Modalities [9]. While the abdominal muscles receive much of the attention for their protective function in the low back, it is the extensors are more important [10]. Decreased trunk extensor endurance has been shown to correlate with low back trouble [11]. Trunk extension exercise training is therefore an important preventive approach for individuals present with low back pain [12]. Certain muscles in particular have been shown to stabilize the low back in various situations [13].

Spinal loading forces were increased during a fatiguing isometric trunk extension effort of torque [14]. Torque output remained constant because as the erector spinal fatigued, substitution by secondary extensors such as the internal oblique and latissmus dorsi muscles occurred [15]. Abnormal motor control has been correlated with low back problems [16]. Poor control of the axis of rotation of trunk during sagital plane movements, asymmetric muscle activation during spinal extension or gait, reduced activity of the transverse abdominus, poor endurance of the spinal extensors and atrophy of the multifidus have all been correlated with low back problems [17].

Endurance is mechanically defined as either the point of isometric fatigue, where the contraction can no longer be maintained at a certain level or as the point of dynamic fatigue, when repetitive work can no longer be sustained at a certain force level [18].

Objectives of the study

To assess the effect of endurance training of extensors with core stability exercise versus core stability exercise in the management of mechanical low back pain, in terms of pain perception.

To assess the effect of endurance training of extensors with core stability exercise versus core stability exercise in the management of mechanical low back pain, in terms of functional disability.

Methodology

Materials

A firm bed Pillow

Patient assessment chart

Data analysis chart

Patient consent form

Study design

The research design of this study is experimental in nature, done on different subjects with pre-test and post -test settings.

Sample size

The study will be carried on 30 subjects, divided into 15 in each group.

Sampling method

Simple random sampling method

Variables Independent variable:

Endurance training to spinal extensors

Core stability exercises

Dependent variable:

Pain

Functional disability

Study settings

Out Patient Department, NIMHANS Hospital, Bangalore

Study duration : Eight months.

Treatment Duration: 3 weeks

Selection criteria

Inclusion criteria:

MLBP subjects with age group of 35 to 45 years.

MLBP subjects with chronic mechanical low back pain.

MLBP both genders.

MLBP duration of symptoms should be between 3 months and above.

Exclusion criteria:

Subjects who have structural deformities.

Patients with inflammatory disease of spine (Ankylosing spondylitis, R.A).

Patients with tumors of spine.

Subjects with infections of spine.

Subjects who has undergone spinal surgery.

Pregnant Women.

Parameters

Low back pain will be measured using Visual Analog Scale.

Functional disability will be measured using modified oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire.

Thirty samples selected from the population divided into two equal groups. The procedure was explained to subject. Both the group underwent a pre test measurement of pain intensity and functional disability.

Group A treated with endurance training of extensors with core stability exercise

Group B treated with core stability exercise.

Hence both groups are treated and after 3 weeks measured pain by visual analogue scale and Functional Disability will be measured using Modified Oswestry Low back pain Disability Questionnaire.

Technique

Endurance training for spinal extensors: The study group was given dynamic back exercises in five different positions. The participant was asked to move the trunk and the suspended limbs 10 times in each position. The treatment is given for 5 days in a week for 3 weeks.

Step-1: Bilateral shoulder lifts

Patient position: prone lying

Procedure: patient is asked to lay down in prone position with arms by the sides of the body, and head and trunk lifted off the plinth from neutral to extension

Step-2: Head and trunk lifts

Patient position: prone lying

Procedure: patient is asked to lay down in prone position with hands interlocked at occiput so shoulders are abducted to 90° and elbows flexed, and head and trunk lifted off the plinth from neutral to extension.

Step-3: Both arms elevated forward

Patient position: prone lying

Procedure: patient is asked to lie down in prone position with both arms elevated forwards, and head and trunk lifted off the plinth from neutral to extension

Step-4: Contra-lateral arm and leg lifts

Patient position: prone lying

Procedure: patient is asked to lay down in prone position and head, trunk and contra lateral arm and leg lifted off the plinth from neutral to extension

Step-5: Both arms and legs lifts

Patient position: prone lying

Procedure: patient is asked to lay down in prone position with both arms elevated forwards and both legs (with knees extended) lifted off the plinth from neutral to extension

Core stability

“Core stability” describes the ability to control the position and movement of the central portion of the body. Core stability training targets the muscles deep within the abdomen which connect to the spine, pelvis and shoulders, which assist in the maintenance of good posture and provide the foundation for all arm and leg movements.

Procedure for core stability exercises:

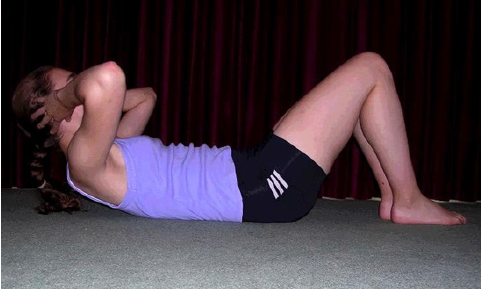

(Figure 1)

Figure 1: Crunches.

Lie on your back with your knees bent and your feet flat on the floor.

“Crunch” or curl your stomach to lift your shoulders just off the floor.

Try not to use your hip flexor muscles to carry out this movement, or use your arms to pull up your head (Figure 2).

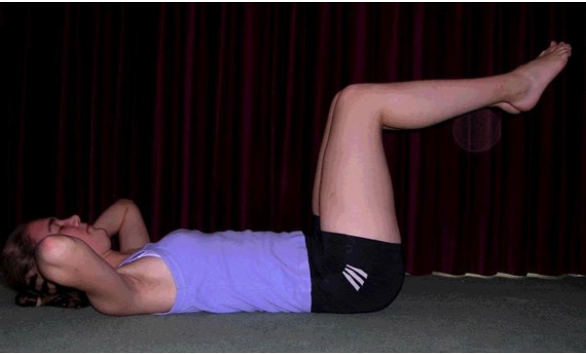

Lie on your back. Raise your legs and bend them so that you form a right angle at your hips and your knees. Place your hands gently on the side of your head. Lift your shoulders off the floor and twist, reaching your right elbow towards your left leg. Return to the floor then repeat, twisting in the opposite direction. Take care not to rock. Your hips and legs should stay as still as possible, allowing your trunk to do all of the work (Figure 3).

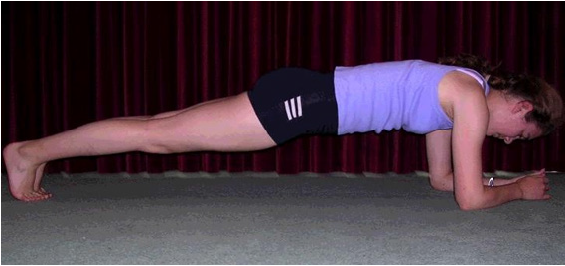

Assume a front-support position resting on your fore-arms with your shoulders directly over your elbows.

Straighten your legs out behind you and lift up your hips to form a dead-straight line from your shoulders to your ankles. You should be balanced on your fore-arms and toes, with your lower abdomen and back working to keep your body straight. Hold for 1 minute.

Aim to complete 3 x 30 crunches, with 30 seconds of recovery between sets. Aim to complete 3 x 30 crunches (15 on each side per set) with 30 seconds of recovery between sets. Aim to be able to hold this position for 3 x 1 minute (Figure 4).

Figure 2: Oblique crunches.

Figure 3: The plank.

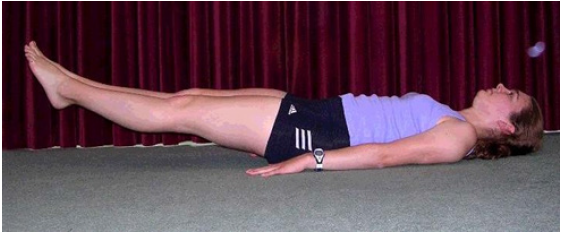

Figure 4: Static leg and back.

Lie on your back with your knees bent and your feet flat on the floor. Lift your pelvis so that you form a bridge position with a straight line running from your shoulders to your knees. Lift your right leg off the floor and extend it so that it continues the straight line. You should be able to feel your left buttock, your back, and lower abdomen working to keep the position. Hold for 30 seconds then repeat on the other leg (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Hamstring rises.

Balance on the floor on your hands and knees. Your back should be flat and your hips parallel to the floor.

Raise one leg behind you until you cannot lift it any higher without rotating your hips or arching your back. The movement should be slow and controlled.

Return the leg to the floor and repeat (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Static straight legs.

Lie on your back with your legs together and your arms by your sides.

Keeping your legs straight, lift your heels approximately 4 inches off the floor.

Hold for 1 minute (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Lowering and Raising Legs

Lie with your back flat on the floor and your legs raised above your hips.

Lower your legs for 30 seconds until the heels are about 4 inches from the floor. Without allowing your heels to touch down, raise them for another 30 seconds. Complete 15 repetitions one leg, and the repeat on the other leg. Concentrate on keeping completely still with your hips square and your back flat. (superman) Do not allow your back to arch. The small of your back should be flat on the floor.

Keep your legs straight and do not allow your back to arch. Try not to move too quickly (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Hundreds

Lie on your back with your arms by your sides. Raise your legs and bend them so that you form a right angle at your hips and knees. Keeping your arms straight and lifting your hands no more than a few inches, gently tap the floor 100 times.

Things to remember when doing core stability exercises:

Do not let your whole stomach tense up. If your upper abdominal muscles “bulge” outwards it means you have cheated by using the large rectus abdominus (six pack) instead of the transverses abdominus (lower abdominals).

Do not brace your lower abdominals too hard; a gentle contraction will suffice. You are trying to improve endurance rather than maximum strength. Only clench them about 50%.

Do not hold your breath as this is a signal that you are not relaxed. You must learn to breathe normally since you will need to breathe when you are running!

It is a good idea to do core stability as part of your cool down after running, or on a cross-training day.

Results

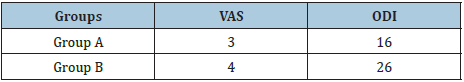

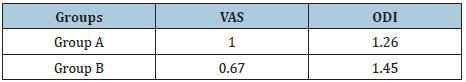

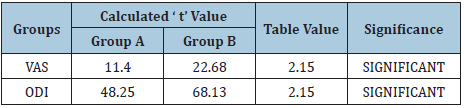

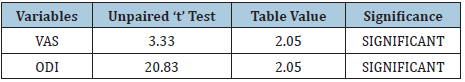

(Figure 9-12 & Table 1-4)

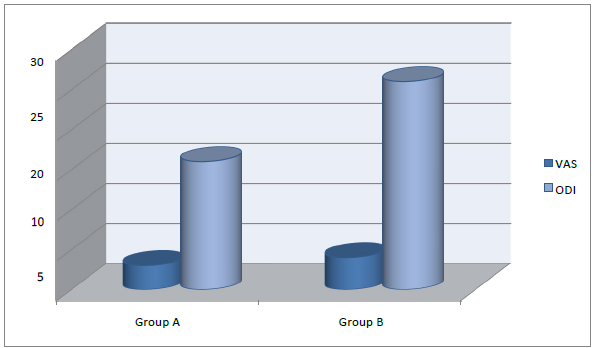

Figure 9: Mean difference between group A & B

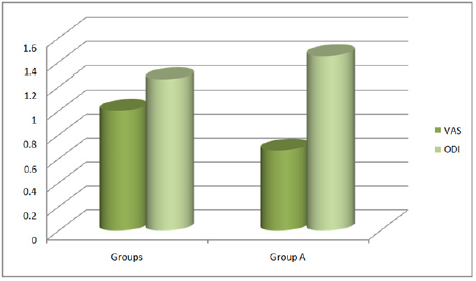

Figure 10: Standard deviation of between group A & B

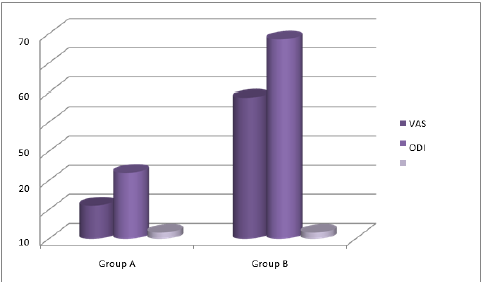

Figure 11: Paired ‘t’ test and table value between group A and group B.

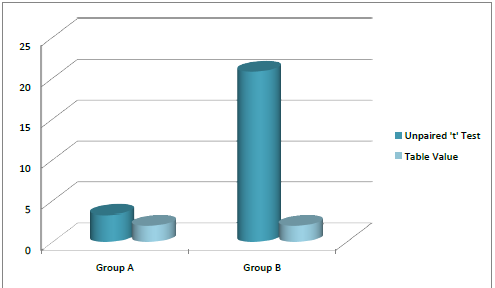

Figure 12: Unpaired‘t’ test and table value between VAS and ODI.

Table 1: Comparison of variables mean difference between group A & B.

Discussion

The study sample comprised of 30 patients. The median time interval between VAS and ODI questionnaire applied before and after therapy was 3 weeks. Among 30 patients, 15 were treated by endurance training of extensors with core stabilization exercise and 15 were treated with core stabilization exercises.

Table 2: Comparison of variables standard deviation between group A & B.

Table 3: Comparison of the paired ‘t’ test and table value between group A & B.

Table 4: Comparison of unpaired ‘t’ test and table value between VAS and ODI.

The pre and post test values were assessed by VAS and ODI in Group A. The mean difference value is 3 and 4 respectively. The standard deviation value is 1 and 0.67 respectively. The paired “t” test value for VAS and ODI is 11.4 and 22.68. The paired “t” test value is more than table value 2.15 for 5% level of significance at 14 degrees of freedom.

The pre and post test values were assessed by VAS and ODI in group B. The mean difference value is 16 and 26 respectively. The standard deviation value is 1.26 and 1.45 respectively. The paired “t” test value for VAS and ODI is 48.25 and 68.13. The paired “t” test value is more than table value 2.15 for 5% level of significance at 14 degrees of freedom.

The calculated “t” values by unpaired “t” test were 3.33 and 20.83. The calculated “t” values were more than the table value 2.05 for 5% level of significance at 28 degrees of freedom. The paired “t” test values have shows that endurance training of extensors with core stabilization exercise was more effective than core stabilization exercise for patients with Mechanical low back pain. The unpaired “t” test values have shown that there was significant difference between two groups in showing improvement in their pain and functional ability for patients with Mechanical low back pain.

While consideration of improving pain and functional ability in patients with Mechanical low back pain, I found there was an effective and good improvement. There was a statistically significant difference in the impact of pain and functional disability of patients with Mechanical low back pain before and after endurance training of extensors with core stabilization exercise. This demonstrates a positive effect of these Exercises on the functional training among patients. The effectiveness of endurance training of extensors with core stabilization exercise for the treatment of Mechanical low back pain was good.

This study has proved that endurance training of extensors with core stabilization exercise is more effective than the core stabilization exercise in mechanical low back pain.

Limitations

1. The study has been conducted on small sized sample only.

2. This study took shorter duration to complete.

3. The study limitations include back pain due to occupations alone.

4. This study is not extended more than 3 weeks for a patient due to time constraint.alone.

Recommendations

1. A similar study may be extended with larger sample.

2. The future study can be compared with other strengthening Exercises also.

3. The endurance training of extensors with core stabilization exercise may be applied to back pain due to any other pathology.

Conclusion

The current study, endurance training of extensors with core stabilization exercise resulted in a positive impact on their functional activities. The VAS and ODI differences in Mechanical low back pain patients before and after treatment were statistically significant.

Through the results, alternate hypothesis is accepted and also the study could be concluded that there is a significant difference between endurance training of extensors with core stabilization exercise and core stabilization in improving the propioception in patients with Mechanical low back pain.

References

- Akuthota V, Ferreiro A, Moore T, Fredericson M (2008) Core stability exercise principles. Current Sports Medicine Reports 7(1): 39-44.

- Axler CT, McGill SM (1997) Low back loads over a variety of abdominal exercises: searching for the safest abdominal challenge. Medicine Science in Sports & Exercise 29: 804-811.

- Barr K, Griggs M, Cadby T (2005) Lumbar stabilization: A review of core concepts and current literature part 1. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation 84(6): 473-480.

- Barr K, Griggs M, Cadby T (2006) Lumbar stabilization: A review of core concepts and current literature part 2. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 86(1): 72-80.

- Bono BM (2004) Low back pain in athletes. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 86(2): 382-396.

- Bergmark A (1989) Stability of the lumbar spine: A study in mechanical engineering. Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica Supplementum 230(60): 1-53.

- Bressel E, Dolny D, Gibbons M (2011) Trunk muscle activity during exercises performed on land and in water. Medicine & Science in Sport & Exercise 43(10): 1927-1933.

- Bressel E, Dolny D, Vandenberg C, Cronin JB (2011) Trunk muscle activity during spine stabilization exercises performed in a pool. Physical Therapy in Sport 13(2): 67-72.

- Chloewick J, McGill SM (1996) Mechanical stability of the in vivo lumbar spine: Implications for injury and chronic low back pain. Clinical Biomechanics 11(1): 1-15.

- Cholewicki J, Van Vliet JJ (2002) Relative contribution of trunk muscles to the stability of the lumbar spine during isometric exertions. Clinical Biomechanics 17: 99-105.

- Ershad N, Kahrizi K, Abadi M, Zadeh S (2009) Evaluation of trunk muscle activity in chronic low back pain patients and healthy individuals during holding loads. Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation 22(3): 165-172.

- Heck JF, Sparano JM (2000) A classification system for the assessment of lumbar pain in athletes. Journal of Athletic Training 35(2): 204-211.

- Haringe ML, Nordgren JS, Arvidsson I, Werner S (2007) Low back pain in young female gymnast and the effect of specific segmental muscle control exercises of the lumbar spine: Aprospective controlled intervention study. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 15: 1264-1271.

- Hodges PW, Richardson CA (1999) Altered trunk muscle recruitment in people with low back pain with upper limb movement at different speeds. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 80: 1005-1012.

- Hayden JA, van Tulder MW, Tomlinson G (2005) Systematic review: Strategies for using exercise therapy to improve outcomes in chronic low back pain. Annals of Internal Medicinem 142(9): 776-785.

- Jull GA, Richardson CA (2000) Motor control problems in patients with spinal pain: A new direction for therapeutic exercise. Journal of Manipulative Physiological Therapeutics 23(2): 115-117.

- Kavcic N, Grenier S, McGill SM (2004) Quantifying tissue loads and spine stability while performing commonly prescribed low back stabilization exercises. Spine 29(20): 2319-2329.

- Kibler BW, Press J, Sciascia A (2006) The role of core stability in athletic function. Sports Medicine 36(3): 189-198.

© 2020 Karthikeyan T. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)