- Submissions

Full Text

Orthopedic Research Online Journal

Bilateral Scapular Osteochondromas in a Congolese Adolescent with Hereditary Multiple Exostosis: Case Report and Review of the Literature

Roger Amisi Kitoko*, Bonza Bomoloko, Pericles Lokangu Kalokola, Junior Mtoro, Gaspard Esiso Afelokoky, Didier Baonga Lembalemba, Victor Esafe Lolongi and Freddy Wami W’ifongo

Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, University of Kisangani, Democratic Republic of Congo

*Corresponding author: Roger Amisi Kitoko, Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, University Clinics of Kisangani, University of Kisangani, Kisangani, Democratic Republic of Congo

Submission: February 08, 2020;Published: February 28, 2020

ISSN: 2576-8875 Volume6 Issue5

Abstract

The aim of this paper is to report an exceptional case of bilateral scapular osteochondromas in an African- American adolescent patient affected by Multiple Hereditary Exostoses (MHE) coming to our observation for multiple bone swelling and deformities in the upper and lower limbs, progressively evolving for more than 10 years. A 17-year-old adolescent had not been able to consult medical training in time because of the precarious socio-economic conditions. He is the youngest of 8 children and was born to an active term pregnancy, complicated by heavy bleeding during the second trimester. The family history of multiple osteochondromas was unremarkable. Standard radiographs of the front thorax and the spine, pelvis, shoulder blades, revealed opaque bony growths in the two shoulder blades.

The surgical excesses proposed with biopsy sampling of these exostoses were not carried out due to insufficient financial means. However, we explained to the patient the probable risk of malignancy of osteochondromas in adolescents and adults and asked him to strictly adhere to the appointment for clinical and radiological monitoring of his osteochondromas

Keywords: Hereditary multiple exostosis; Bilateral scapular osteochondromas; African-American adolescent; DRC

Introduction

Multiple hereditary exostosis (MHE) is a rare disease. Its prevalence is estimated at least one in 50,000 peoples [1-3]. Most often located in the proximal humerus, distal femur and proximal tibia, cartilaginous exostoses come from metaphyseal regions of growing enchondral bones [2,4]. Osteochondromas increase in size throughout childhood and stop growing when skeletal maturity is reached. Although osteochondromas are often clinically asymptomatic, symptoms such as pain and orthopedic deformities, i.e. differences in bone length, forearm deformities and varus-valgus malposition of the knee usually lead at the diagnosis of HME during the first decade of life [1,2]. If the growth and clinical symptoms of osteochondromas reappear in adults, malignant transformation of generally benign growing tumors should be suspected. Malignant degeneration into chondrosarcoma is estimated at 8% of cases [5]. Regular monitoring of a diagnosed malignancy and surgical treatment of patients with MHE are necessary [5,6].

The aim of this paper is to report an exceptional case of bilateral scapular osteochondromas in an African-American adolescent patient affected by Multiple Hereditary Exostoses (MHE) coming to our observation for multiple bone swelling and deformities in the upper and lower limbs, progressively evolving for more than 10 years. In addition, nowadays in the literature, no case of bilateral scapular osteochondroma in an African American adolescent is described. We report the case of a congolese adolescent patient, affected by MHE with bilateral scapular osteochondromas.

Case Report

A 17-year-old Congolese adolescent suffering from hereditary multiple exostosis was referred to our hospital for multiple bone swellings and significant deformities in the upper and lower limbs progressively evolving for more than 10 years and a delay in weight-loss development. He had not consulted medical training in time because of the precarious socio- economic conditions. He is the youngest of 8 children and was born to an active term pregnancy, complicated by heavy bleeding during the second trimester. The family history of multiple osteochondromas was not present in the parents and grandparents.

During physical examination, we noted significant weight loss and a delay in weight-loss development (the patient tall was 135cm and weighing 34kg), multiple and symmetrical, generalized, hard, painless and immobile bone swelling at the level of the pelvis, the dorsal column, the joints of the upper limbs (in particular the shoulders, elbows, wrists and hands in the form of bulky firm nodes) and lower (the hips, knees and ankles) and multiple significant deformations and symmetrical, in the form of curvature and shortening of the two forearms and wrists and hands.

Upon close examination of both shoulders, we noted a slightly visible and clearly palpable bilateral swelling on both sides in the body of the scapula. The range of motion of the two shoulders was not impaired. The motor skills and sensitivity of the upper limbs were retained.

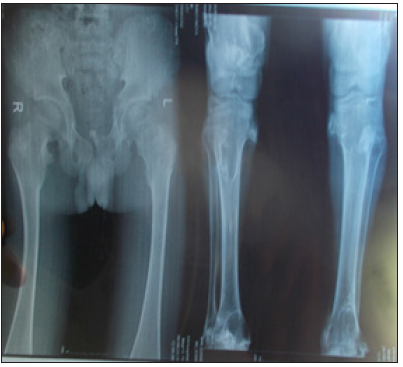

Despite the absence of scapulothoracic pain, standard radiographs of the skeleton, especially of the chest, revealed bilateral osteochondromas at the level of the two shoulder blades without obvious signs of malignant degeneration (Figure 1 & 2). Interestingly, these X-rays did not detect any signs of malignancy. Specialized explorations including the CT, MRI or biopsy were not carried out due to the limited technical platform.

Figure 1: Standard radiograph of the front two right and left humerus, two right and left shoulder blades, of the spine: bony outgrowth of the outer edge of the two shoulder blades, of the upper metaphysis of the two humerus, deformation of the right humeral shaft in varus, vertebral deformity in scoliosis.

Figure 2: Standard frontal X-ray of the two bones of the forearms, wrists and hands: multiple and symmetrical bony growths of the proximal and distal metaphyses of the two bones of the two forearms and of the phalanges with curvatures of the two radiuses.

In front of this clinical and radiological diagnosis of bilateral scapular osteochondromas, we proposed to perform surgical excesses with biopsy sampling of these exostoses. But due to the lack of sufficient financial means, surgical treatment had not been carried out. However, we explained to the patient the high risk of malignancy of osteochondromas in chondrosarcoma in adolescents and adults and asked him to strictly observe the appointment for clinical and radiological monitoring of his osteochondromas.

Discussion

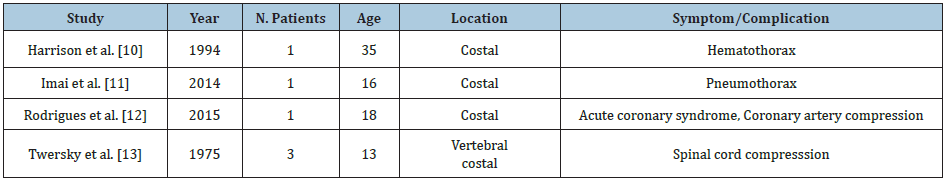

Multiple hereditary osteochondromas are the most common [1,2]. The development of HME occurs mainly due to the lack of EXT1, EXT2 or EXT3 genes, the EXT genes are designated as tumor suppressor genes. In addition, the manifestation of HME appears to be higher in men (male / female ratio: 1.5: 1). While people with an EXT1 gene mutation would be more severely affected by MHE, the manifestation of exostoses of the shoulder also seems more likely in these patients. In addition, a malignant sarcomatous change appears to be more likely in patients with palpable exostoses of the shoulder compared to any other anatomical site [6,7]. In addition, the case presented shows the topographic occurrence of osteochondromas in patients with MHE. Cartilaginous exostoses are very often located around the knee. The probability of knee involvement in affected people is described with 94% [2]. In addition to the location of osteochondromas near the knee, bone tumors covered with cartilage are very often located in the proximal humerus (50%), the proximal forearm (radius 38%, ulna 37%) and distal ulna (80%) [2,8]. The risk of a patient with MHE having a spinal injury is described with 27% [9]. The reported prevalence ranges from 14 to 45% (2.7). Among the rare but serious complications caused by osteochondromas of the chest wall described in the literature as spontaneous hemothorax, pneumothorax, extrinsic coronary compression and compression of the spinal cord (Table 1) ; [10-13], malignant transformation [1-6] is the most feared situation for patients suffering from HEM. In addition to taking the patient’s history and performing a detailed physical examination, simple x-rays of areas that cannot be examined manually, i.e., chest, pelvis and scapula, should be performed. If differences are seen in regular examinations, other imaging diagnoses such as conventional radiographs should be performed, followed by crosssectional imaging techniques, such as CT and MRI [14] ; (Figure 3).

If the diagnosed tumor appears to be aggressively growing in all cases, an MRI should be performed to detect the size of the lesion before performing a biopsy by an orthopedic or surgical specialist. In cases of confirmed malignancy, surgical resection of the tumor is necessary as far as possible. For conservative treatment, in addition to standardized pain management, the use of bisphosphonates is considered useful in the management of refractory pain in patients with MHE [15,16]. With regard to shoulder exostoses, various types of minimally invasive open and endoscopic surgical techniques are described [7,14,17-19]. Due to possible malignant transformation and limited non-surgical treatment options in chondrosarcoma, minimally endoscopic invasive procedures should be viewed with a critical eye [17-19].

Figure 3: Standard radiograph of the pelvis, the two femurs, the two knees and the two bones of the two legs: multiple and symmetrical bony growths of the proximal and distal metaphyses of the two femurs, the two tibias and the two iliac bones.

Table 1: Studies reporting rare complications caused by chest wall osteochondromas.

Conclusion

The clinical diagnosis of hereditary multiple osteochondroma in the long bones is easy but difficult in the case of scapular localization. Its prevalence appears to be less common in African- American adolescents. The standard chest X-ray is therefore necessary to make the diagnosis. Its treatment is often conservative, but clinical and radiological monitoring must be regular and careful in adolescents and adults to detect malignant degeneration.

References

- Bovee JV (2008) Multiple osteochondromas. Orphanet J Rare Dis 3: 3.

- Schmale GA, Conrad EU, Raskind WH (1994) The natural history of hereditary multiple exostoses. J Bone Joint Surg Am 76(7): 986-992.

- Alba A, Carleton L, Dinkel L (2012) Increased lead levels in pregnancy among immigrant women. J Midwifery Womens Health 57(5): 509-514.

- Hennekam RC (1991) Hereditary multiple exostoses. J Med Genet 28: 262-266.

- Jundt G, Baumhoer D (2010) Hereditary bone tumors. Pathologe 31: 471-476.

- Hameetman L, Bovee JV, Taminiau AH (2004) Multiple osteochondromas: clinicopathological and genetic spectrum and suggestions for clinical management. Hered Cancer Clin Pract 2(4): 161-173.

- Clement ND, Ng CE, Porter DE (2011) Shoulder exostoses in hereditary multiple exostoses: probability of surgery and malignant change. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 20(2): 290-294.

- Vogt B, Tretow HL, Daniilidis K (2011) Reconstruction of forearm deformity by distraction osteogenesis in children with relative shortening of the ulna due to multiple cartilaginous exostosis. J Pediatr Orthop 31(4): 393-401.

- Roach JW, Klatt JW, Faulkner ND (2009) Involvement of the spine in patients with multiple hereditary exostoses. J Bone Joint Surg Am 91(8): 1942-1948.

- Harrison NK, Wilkinson J, O’Donohue J (1994) Osteochondroma of the rib: an unusual cause of haemothorax. Thorax 49: 618-619.

- Imai K, Suga Y, Nagatsuka Y (2014) Pneumothorax caused by costal exostosis. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 20(2): 161-164.

- Rodrigues JC, Mathias HC, Lyen SM (2015) A novel cause of acute coronary syndrome due to dynamic extrinsic coronary artery compression by a rib exostosis: multimodality imaging diagnosis. Can J Cardiol 31(10): e9- 1303e11.

- Twersky J, Kassner EG, Tenner MS (1975) Vertebral and costal osteochondromas causing spinal cord compression. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 124(1): 124-128.

- Soldatos T, McCarthy EF, Attar S (2011) Imaging features of chondrosarcoma. J Comput Assist Tomogr 35(4): 504-511.

- Winston MJ, Srivastava T, Jarka D (2012) Bisphosphonates for pain management in children with benign cartilage tumors. Clin J Pain 28(3): 268-272.

- WHO (2011) WHO’s cancer pain ladder for adults.

- Perez D, Ramon CJ, Caballero J (2011) Minimally-invasive resection of a scapular osteochondroma. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 13(5): 468-470.

- Fukunaga S, Futani H, Yoshiya S (2007) Endoscopically assisted resection of a scapular osteochondroma causing snapping scapula syndrome. World J Surg Oncol 5: 37.

- Frost NL, Parada SA, Manoso MW (2010) Scapular osteochondromas treated with surgical excision. Orthopedics 33(11): 804.

© 2020 Roger Amisi Kitoko. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)