- Submissions

Full Text

Orthopedic Research Online Journal

Examining the Impact of a Six-Week Orthopaedic Skills Course on Resident Confidence and Preparedness for Transition to Registrar Practice

Conor Gouk*, Cas ey Steele, William Cundy, Nicolle Hackett, Randipsingh Bindra and Francois Tudor

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Australia

*Corresponding author:Conor Gouk, Gold Coast Hospital and Health Service, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Southport, QLD, Australia

Submission: June 12, 2019;Published: June 20, 2019

ISSN: 2576-8875 Volume5 Issue4

Abstract

Objectives: To determine whether a six-week orthopaedic surgical skills course could increase resident skills and confidence before transitioning to registrar practice.

Methods: Unaccredited registrars, orthopaedic trainees, and orthopaedic consultants, through a departmental peer-reviewed process and survey, developed a six-session course (“Registrar Academy”) that included basic knowledge and essential practical skills training for residents with interest in becoming orthopaedic registrars. Mixed method quantitative and qualitative evidence was sought via a 14-item and 18-item Likert scale questionnaire coupled with open-ended questions.

Results: Results were qualitatively synthesised using quantitative and qualitative data. Thirteen residents participated in the course. All residents agreed to statements indicating they felt unprepared to work as an orthopaedic registrar and were not confident in performing various core tasks required. After completing the course, residents indicated greater confidence or comfort in all these areas and felt better prepared for the transition to registrar. There was broad approval of the course among participants. Every participant who completed the final questionnaire agreed or strongly agreed that they enjoyed the course and that it taught usable, reproducible practical skills and increased their orthopaedic knowledge. This group also uniformly agreed or strongly agreed that the course improved their patient care and patient safety.

Conclusion: Residents feel unprepared for their transition to an orthopaedic registrar and lack confidence in several core competencies. A supplemental “Registrar Academy” is an effective way to improve knowledge, confidence, and practical skills for residents wishing to transition to a registrar position.

Keywords: Residents; Registrar academy; Orthopaedic registrar; Orthopaedic knowledge

Abbreviations: ATLS: Advance Trauma Life Support; PGY: Post Graduate Year

Introduction

The transition from resident to registrar constitutes a steep learning curve in most medical practitioners’ careers [1]. In surgical disciplines, registrars are expected to have a strong knowledge base and an array of practical and operative skills. Due to the current model of training, junior doctors often have reduced exposure to the operating theatre, and time constraints can limit the amount of ‘on the job’ teaching provided by consultants and senior colleagues [2]. Inadequate training not only potentially compromises patient care [3], but can lead to undue stress on junior registrars, affecting work satisfaction and overall quality of life [4]. Established skills courses such as Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) have generally been reported as essential to overall training; however, these are usually broad in nature, have a rigid structure and are designed to be completed over the course of one to three days.

Furthermore, these courses can be financially burdensome on residents [5]. Previous studies have shown favourable results with the implementation of specialty-specific skills courses [6,7]. In particular, a work-based structure with repeated episodes of training spaced out over weeks to months have been suggested as the most favourable format [8,9]. We aimed to develop and trial a self-titled “Registrar Academy” in the hope to better prepare residents for the transition to a registrar in trauma and orthopaedics. Through a peer-reviewed process to develop the curriculum, we intended to provide a course that covered the essential knowledge and skills required of a first-year registrar within the field of trauma and orthopaedics.

Materials and Methods

A curriculum was developed by a peer review process involving current unaccredited registrars, orthopaedic trainees, and consultants. Twenty skills modules were initially proposed to cover the skills required at this level. Using the information gathered during the peer review process, course designers reduced the number of modules to six. This then corresponded to the proposed course duration of one lesson module per week.

A total of 13 places were offered to residents within our health trust through a Health Service Education bulletin issued by the educational department. All 13 positions offered to residents interested in a career in Orthopaedics were filled on a first come first serve basis. The average post-graduate year (PGY) of participants was PGY 2.

Teaching sessions were held outside of work hours, were led by fellowship-trained orthopaedic surgeons, and also involved unaccredited registrars and orthopaedic trainees. Three days prior to each teaching session, participants were provided with prereading relevant to the upcoming module; one compulsory article and two optional. The modules were: Emergency Management of Trauma, Safe Patient Positioning and Basic Surgical Instruments, Suturing and Soft Tissue Management, Tendon Repair, Operative Planning and Templating, and Basics of Operative Fracture Fixation. All were primarily practically orientated with a small amount of didactic teaching.

Participants were asked to complete a 14-item Likert scale questionnaire before the first module. The questionnaire also included a final free text section for additional comments. Similarly, upon completion of the final module, participants were asked to complete an 18-item Likert scale questionnaire that included 12 of the original pre-course questions and six new questions intended to evaluate the effectiveness of the course. In addition, three free text sections were included asking participants to include positives of the course, negatives, and a final question “how do you feel this course changed your practice?” There were no set outcomes defined for the course. Participants were also invited to place any additional comments on the back of their surveys. All surveys were anonymous and did not gather demographic data such as age or gender.

Results and Discussion

Results

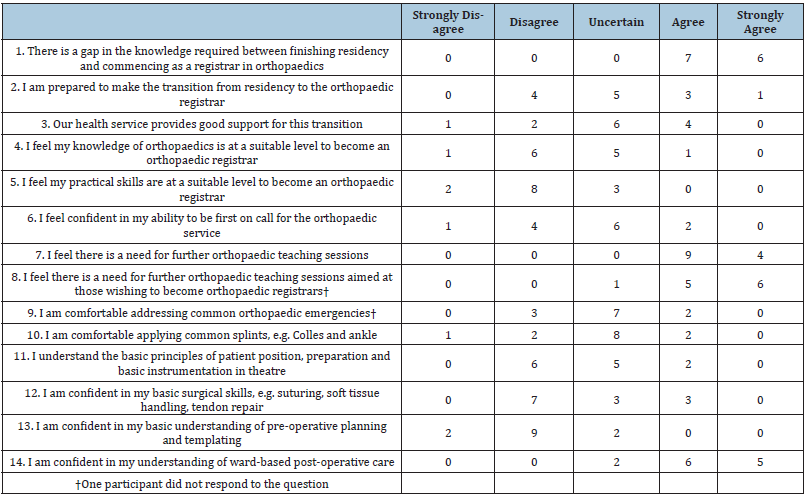

Thirteen participants returned the pre-course questionnaire. Responses are shown in Table 1 as the total number of participants who responded in each of the Likert scale categories. All participants agreed or strongly agreed that there is a gap in the knowledge required between finishing residency and commencing as a registrar in orthopaedics. Likewise, all participants agreed or strongly agreed there is a need for further orthopaedic teaching sessions. The pre-course survey identified a lack of confidence in all participants’ knowledge and practical skills. Eleven of 13 participants agreed with the statement that they had confidence in their understanding of ward-based post-operative care.

Table 1:Pre-course questionnaire responses

Conversely, 11 of 13 participants disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement that they had confidence in their knowledge about pre-operative planning and templating, and no participant agreed or strongly agreed with it. No participant strongly agreed to be comfortable addressing common orthopaedic emergencies or applying common splints. Furthermore, no participant strongly agreed to confidence in basic surgical skills or in their ability to be first on call for the orthopaedic service.

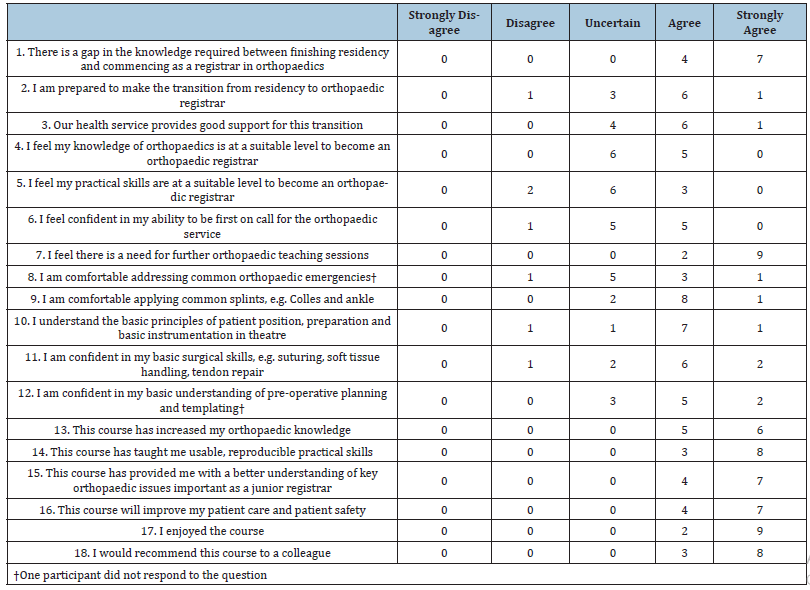

Eleven participants responded to the post-course questionnaire (Table 2). All participants who submitted a final course survey agreed or strongly agreed that they enjoyed the course, they would recommend it to a colleague, the course taught useful and reproducible practical skills, and the course increased their orthopaedic knowledge. All these participants endorsed the sentiment that the course will improve their delivery of patient care and patient safety.

Table 2:Post-course questionnaire responses.

Open-ended responses to questions shared similar content and themes. They generally reflected the ratings provided on the Likert scale. Representative examples of comments made in the pre-course survey comments section included:

1. Did not apply for registrar position secondary to feeling unprepared, this course if perfect, thanks.

2. Teaching we receive is opportunistic but great, and we just need more of it

In the post-course survey, examples of things listed as ‘positives’ in regard to the course itself included:

1. Practical skills.

2. Resources

3. Excellent teachers.

4. Good balance in sessions.

Examples of what could be improved about the course included:

1. Could be spread over more sessions.

2. Some gaps still in knowledge.

3. Covering a lot of information in a short time.

In response to “how do you feel this course has changed your practice?” Participants responded:

1. Aware of my limitations but more confident in my abilities.

2. More confident in starting as a registrar.

3. Improved surgical skills and knowledge.

4. Better knowledge base for an on-call, better practical skills.

Discussion

Our results show that residents lack confidence in several critical aspects of orthopaedic care at the time they are transitioning to a registrar position. Most residents feel inadequately prepared to become orthopaedic registrars. Questionnaire responses indicate that they generally lack confidence in taking a leading role in the orthopaedic service including lack of confidence ranging from an orthopaedic emergency response to common splinting. Selfperception of competence in basic surgical skills and equipment, and pre-operative planning and templating is low despite being on the verge of becoming an orthopaedic registrar.

By implementing a ‘Registrar Academy,’ we aimed to determine whether we could increase confidence in those making the transition from resident to registrar and identify areas where we could improve for future years. Participants agreed or strongly agreed that there is a gap in the knowledge required between finishing residency and commencing as a registrar in orthopaedics before and after the course. However, the number of participants who endorsed that they were now prepared to make the transition from residency to orthopaedic registrar increased after the sessions. This suggests that the six-week course had a positive effect on participants’ preparedness. Further supporting this interpretation of the results is the responses to the question “I feel my practical skills are at a suitable level to become an orthopaedic registrar.” Before the course, no participants agreed with that statement, and 10 of 13 disagreed with it at some level. However, after the course, three participants agreed, which seems to indicate the training program had conveyed knowledge and practical skills perceived as critical to working as an orthopaedic registrar. The increased agreement with “Our health service provides good support for this transition” in the post-course survey suggests participants had a more favourable view of the health service’s training because of the course itself.

The number of people who reported feeling confident to be first on call for the orthopaedic service or addressing common orthopaedic emergencies increased after the training sessions. Confidence with common splints also increased among participants with additional training, as did patient positioning, preparation, and surgical instrumentation. Perhaps the most significant gains in self-perceived confidence were in pre-operative planning and templating. No trainees reported confidence in these skills before the course, while nearly two-thirds of respondents did so after the course.

Participants were enthusiastic about the course both in their excitement to enroll and in their subjective reports about the course itself. The apparent attrition rate of two trainees did not reflect course dropout; instead these individuals were simply absent from the final teaching session due to work commitments, and thus a final questionnaire was not obtained.

There was repeated constructive feedback from participants that the duration of the course was too short and that the content could have been spread over more sessions. Considering that course developers have initially proposed 20 sessions, future improvements to the Registrar Academy may include additional sessions with a slower pace and time for concept reinforcement. Since this training course takes place outside of work hours, a potential risk of extending the duration of the course would be increased participant attrition. However, this may not be a practical issue given the favourable reception of the course, the perceived utility, and the desire for additional training voiced by course participants.

Our pilot study was conducted at a single site within a single training program, and the sample size was relatively small. These factors limit the broader generalisability of the results. With a lack of control or comparator group, we cannot specifically compare the Registrar Academy to “no intervention” or standard educational practice. Nevertheless, improvements in knowledge and confidence that resulted from the Registrar Academy supports pursuing further study of the topic and ongoing implementation of the program. Student evaluations that include structured feedback mechanisms are a reliable means of discovering and implementing improvements in teaching and training [10,11]. A similar improvement to the data gathering process would be to implement anonymous identifiers to track improvement in individual participants rather than the group.

Interestingly, participants reported confidence in wardbased work medical-surgical practice before the course. This may reflect the fact that residents spend substantially more time as the principal provider of patient care on the wards than they do in the surgical theatre. While patient care duties are an essential part of professional surgical practice, this discrepancy between confidence on the wards and with orthopaedic surgical practice suggests opportunities for a better training approach toward the latter. While programs such as the Registrar Academy may begin to fill that training gap, specific electives may be added to core residency programs that teach and foster in-theatre and out-oftheatre orthopaedic skills may improve resident preparedness and confidence for their transition to registrar.

Conclusion

Our short course improves participants’ confidence, abilities, and satisfaction with the educational provisions of our department and health service about trauma and orthopaedics. As such this is likely to impact positively in junior doctors’ working lives thereby decreasing work-related stress and increase the quality and safety of the care patients receive.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank the Synthes Australia for providing imitation bones, plates, drills and other hardware for two of the practical sessions.

Conflict of Interest

We declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kilminster S, Zukas M, Quinton N, Roberts T (2011) Preparedness is not enough: understanding transitions as critically intensive learning periods. Medical education 45(10): 1006-1015.

- Rashid MS (2018) An audit of clinical training exposure amongst junior doctors working in trauma & orthopaedic surgery in 101 hospitals in the United Kingdom. BMC medical education 18(1): 1.

- Minter RM (2015) Transition to surgical residency: a multi-institutional study of perceived intern preparedness and the effect of a formal residency preparatory course in the fourth year of medical school. Academic medicine 90(8): 1116-1124.

- Association AM (2008) AMA survey report on junior doctor health and wellbeing. ACT, Australia: Australian Medical Association.

- Campbell B, Heal J, Evans S, Marriott S (2000) What do trainees think about advanced trauma life support (ATLS)? Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England 82(4): 263-267.

- Egol KA, Phillips D, Vongbandith T, Szyld D, Strauss EJ (2015) Do orthopaedic fracture skills courses improve resident performance? Injury 46(4): 547-551.

- Sonnadara RR, Van Vliet A, Safir O, Alman B, Ferguson P, et al. (2011) Orthopedic boot camp: examining the effectiveness of an intensive surgical skills course. Surgery 149(6): 745-749.

- Burnand H, Mutimer J (2012) Surgical training in your hands: organising a skills course. The clinical teacher 9(6): 408-412.

- Byrne AJ, Pugsley L, Hashem M (2008) Review of comparative studies of clinical skills training. Medical Teacher 30(8): 764-777.

- Irby D, Rakestraw P (1981) Evaluating clinical teaching in medicine. Journal of Medical Education 56(3): 181-186.

- Eaton DGM, Levene MI (1997) Student feedback: influencing the quality of teaching in a paediatric module. Medical education 31(3): 190-193.

© 2019 Conor Gouk. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)