- Submissions

Full Text

Open Journal of Cardiology & Heart Diseases

Patient Blood Management Strategies During Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic

Mathur G*

Department of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA

Department of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, University of California Irvine, Irvine, CA

*Corresponding author: Mathur G, Department of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, University of Southern California, Children’s Hospital, CA Email: mathurgagan@gmail.com

Submission: September 27, 2022;Published: November 18, 2022

ISSN 2578-0204Volume4 Issue1

Abstract

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has stressed out all aspects of global healthcare including blood supply. Options for global healthcare to maintain continuous and robust blood supply include, increasing blood donations and decreasing blood use to expand available blood supply. At this time, more than ever, Patient Blood Management (PBM) strategies can help reduce blood utilization, improve patient outcomes, and help mitigate ever looming blood shortages.

Keywords: Coronavirus; COVID-19; Blood supply; Blood shortage; Patient blood management; PBM, Blood utilization; Anemia management

Introduction

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused widespread disruptions and stressed out all aspects of global healthcare. Blood supply being one which has been significantly affected. In first few weeks of pandemic, American Red Cross (ARC) reported approximately 5,000 blood drives were canceled resulting in approximately 150,000 fewer units collected (American Red Cross, Hospital Support Communication, March 19, 2020). Many regional and community blood centers worldwide also reported cancellations of thousands of collections. This disruption of blood supply continues 2.5 yrs into the pandemic. Blood centers are encouraging healthy donors to continue donating to maintain critical blood supply. Blood centers are still lagging and trying to catch up on the blood demand worldwide. Cancellation of elective surgeries helped initially as supply and demand balanced. However, urgent/emergent surgeries, trauma, transfusion dependent patients, etc. still needed robust transfusion support during this pandemic. And now that everyone is back to “new normal”, the blood demand has gone up to pre-pandemic levels, but the blood supply is still constrained because donors are still not showing up at blood drives and donor center to match prepandemic numbers.

The options for global healthcare to maintain continuous and robust blood supply include,

1) increasing donations and 2) decreasing nonessential blood transfusions. Given the fear and

anxiety in public about COVID-19 and local government’s Coronavirus guidelines for social

distancing and other restrictions [1], brining healthy blood donors to blood centers and blood

drives continues to be a challenge. On the other hand, Patient Blood Management (PBM)

strategies, if implemented effectively, can significantly reduce the blood utilization. The most

robust evidence for this approach comes from experience during the HIV/HCV epidemic in

US, where clinicians were transfusing at much lower rates due to fear of contamination of

the donated blood [2]. PBM is an evidence-based, multidisciplinary team approach to reduce

blood loss, optimize hemostasis, manage anemia, and utilize blood transfusions appropriately

with an aim to optimize patient care and improve outcomes [3,4]. PBM strategies provide

alternative options to clinicians before they pull trigger for blood transfusion. Reducing blood

use is not the primary goal of PBM, but it is an outcome of providing better patient care. During

the COVID-19 pandemic these alternatives to transfusions, where

applicable, can lessen the stress on the blood supply and allow

clinicals to continue to meet medical and surgical requirements of

the patients. PBM strategies that can be implement by the hospitals

during these difficult times include,

A. Evidence-based transfusion practices

B. Blood conservation

C. Anemia management

D. Patient education and involvement

Evidence-based transfusion practices

Blood shortages and risks associated with each unit of blood component calls for strict adherence to evidence-based transfusion guidelines. A restrictive hemoglobin (Hgb) threshold of 7g/dL is suggested for most stable patients (8g/dL in patients with preexisting cardiovascular disease) [5]. During COVID-19 pandemic, a lower Hgb threshold could be considered in asymptomatic patients who are not actively bleeding and are hemodynamically stable. There is absolutely no role for 2 or more units of RBC unit orders in patients without ongoing blood loss. Single unit red cell transfusions should be used as standard orders for non-bleeding patients. Additional units should only be prescribed, if clinically indicated, after re-assessment following single unit transfusion. Transfusion decisions should be influenced by symptoms, hemodynamic stability, and (not just) Hgb concentration.

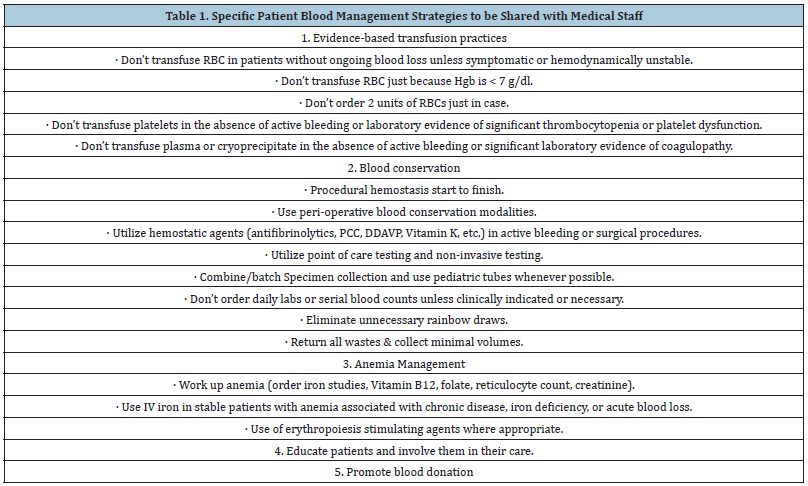

Like RBCs, restrictive platelets, plasma, and cryoprecipitate transfusion strategies should also be adopted. Platelets should be reserved only for patients with active bleeding or laboratory evidence of significant thrombocytopenia or platelet dysfunction [6]. Plasma or cryoprecipitate should be given only to patients with active bleeding or significant laboratory evidence of coagulopathy [7-10]. Transfusion requests not meeting the guidelines and multiple unit orders should be reviewed. If resources are available, changes in blood order-sets, Best Practice Alerts (BPA), and Clinical Decision Support (CDS) should be considered. Specific evidencebased transfusion practices that can be conveyed to medical staff are presented in Table 1.

Table 1:Specific Patient Blood Management strategies to be shared with medical staff.

Blood conservation

Procedural hemostasis, rapid detection and management of blood loss, and evidence-based use of peri-operative blood conservation modalities (e.g. Cell Saver, Acute Normovolemic Hemodilution, etc.), if not already in place, should be promoted. Hemostatic agents such as antifibrinolytics, Prothrombin Complex Concentrates (PCC), Desmopressin, Vitamin K, etc. should be used to minimize bleeding when indicated in active bleeding or surgical procedures [11-13]. For all hospitalized patients, iatrogenic blood loss from frequent and/or avoidable lab draws should be minimized [14-16]. Specimen collection should be combined/batched, pediatric tubes should be used whenever possible, daily and repeat laboratory testing should be discouraged [17], and rainbow draws should be eliminated [18]. Point of Care (POC) testing and noninvasive testing should be utilized, if available. These strategies not only conserve patients own blood but are also important to avoid unnecessary exposure of healthcare workers to confirmed COVID-19 cases or Patient Under Investigation (PUI) and conserves Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) which have also been in short supply [19]. Specific blood conservation strategies that can be conveyed to medical staff are presented in Table 1.

Anemia management

Anemia is common in hospitalized patients, approximately half of the hospitalized patients are admitted with varying severity of anemia and approximately one-third of patients undergoing elective surgery are anemic [20]. The anemia can also be acquired or be worsened during hospital admission. Anemia is often accepted and ignored as a harmless problem and rarely makes to top of patient’s problem list. The reality is, anemia is an independent risk factor for significant morbidity and mortality, as high as 30-40% in certain patient populations. Anemia is associated with increased risk of hospitalization or readmission, length of stay, loss of function, diminished quality of life, and post-operative infection and sepsis [21-23]. Diagnosing & treatment of root cause of anemia (decreased production of RBCs, increased destruction of RBCs, or blood loss) is often ignored. RBC transfusion is often used as a default treatment for anemia, which should be strictly discouraged during this time. Depending on underlying etiology, anemia management involves nutritional supplementations (iron, vitamin B12 and folate), changes in medication, treatment of chronic inflammatory or autoimmune conditions, managing underlying malignancy, or other etiology specific interventions.

Iron deficiency is most common cause of anemia and even if not, the primary etiology, it often coexists and contributes to worsening or delay in hemoglobin recovery. Iron deficiency should be identified and managed quickly. IV iron should be given to stable patients with anemia associated with chronic disease, iron deficiency, or acute blood loss [24-26]. Various safe and effective formulation of IV iron are available and should be selected at hospital level based on availability, logistic convenience, and costeffectiveness [27]. Erythropoiesis stimulating agents should be used where appropriate. Specific anemia management strategies that can be conveyed to medical staff are presented in Table 1.

Patient education and involvement

Informed clinicians can help patient make informed choice about their care and blood transfusions. During this COVID-19 pandemic, given limited resources and swimming in uncharted territories, patient-centered decision making is especially important. Patients should be educated and involved as a part of a team to fight COVID-19.

Promoting Blood Donations

Although, in patients with clinical disease, novel coronavirus nucleic acids are found in the serum or plasma and in some instances in lymphocytes, but there is no current evidence of transfusion transmission of SARS-CoV-2 (novel coronavirus causing COVID-19) [28]. Hospitals should assist blood centers to maintain a safe and adequate blood supply by encouraging healthy people (no exposure to a patient with COVID-19, not in a high-risk group and physically able to do so) to donate blood. Blood centers are taking extreme precautions and screening donors to prevent community spread of COVID-19. Healthy people should be directed to blood center’s websites to make an appointment.

Conclusion

COVID-19 pandemic, like other pandemics, epidemics, natural disasters, mass shooting, and terrorist attacks that world has faced, is stressing and testing blood supply. Altruistic healthy donors are stepping forward to support our blood supply, but hospitals should strictly adopt and implement PBM strategies to help alleviate stress on the health system, conserve limited laboratory resources, and to be prepared for impending blood shortages. PBM initiatives are increasingly adopted across the globe as part of standard of care and globally defined as “Patient blood management is a patientcentered, systematic, evidence-based approach to improve patient outcomes by managing and preserving a patient’s own blood, while promoting patient safety and empowerment” [29].

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that he has no conflicts of interest relevant to the manuscript submitted.

References

- Government Response to Coronavirus, COVID-19 (2020).

- Surgenor DM, Wallace EL, Hale SG, Gilpatrick MW (1988) Changing patterns of blood transfusions in four sets of United States hospitals, 1980 to 1985. Transfusion 28(6): 513-518.

- Patient Blood Management, 2020.

- What is Patient Blood Management (PBM)? 2020.

- Carson JL, Grossman BJ, Kleinman S, Tinmouth AT, Marques MB, et al. (2012) Red blood cell transfusion: A clinical practice guideline from the AABB. Ann Intern Med 157(1): 49-58.

- Kaufman RM, Djulbegovic B, Gernsheimer T, Kleinman S, Tinmouth AT, et al. (2015) Platelet transfusion: A clinical practice guideline from the AABB. Ann Intern Med 162(3): 205-213.

- Roback JD, Caldwell S, Carson J, Davenport R, Jo Drew M, et al. (2010) Evidence‐based practice guidelines for plasma transfusion. Transfusion 50(6): 1227-1239.

- Holbrook A, Schulman S, Witt D, Vandvik PO, Fish J, et al. (2012) Evidence-based management of anticoagulant therapy: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis: American college of chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2012;141(2): e152S-

- Muller M, Arbous MS, Spoelstra-de Man AM, Vink R, Karakus A, et al. (2015) Transfusion of fresh-frozen plasma in critically ill patients with coagulopathy before invasive procedures: A randomized controlled trial (CME). Transfusion 55(1): 26-35.

- Green L, Bolton-Maggs P, Beattie C, Cardigan R, Kallis Y, et al. (2018) British society of haematology guidelines on the spectrum of fresh frozen plasma and cryoprecipitate products: Their handling and use in various patient groups in the absence of major bleeding. Brit J Haematol 181(1): 54-67.

- Henry DA, Carless PA, Moxey AJ, O'Connell D, Stokes JB, et al. (2011) Anti-fibrinolytic drugs for reducing blood loss and the need for red blood cell transfusion during and after surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4: CD001886.

- CRASH-2 Trial Collaborators (2010) Effects of tranexamic acid on death, vasoocclusive events, and blood transfusion in trauma patients with significant haemorrhage (CRASH-2): A randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 376(9734): 23-32.

- WOMAN Trial Collaborators (2017) Effect of early tranexamic acid administration on mortality, hysterectomy, and other morbidities in women with post-partum haemorrhage (WOMAN): an international, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 389(10084): 2105-2116.

- Gattinoni L and Chiumello P (2002) Anemia in the intensive care unit: how big is the problem? Transfus Altern Transfus Med 4(4): 118-20.

- Thavendranathan P, Bagai A, Ebidia A, Detsky AS, Choudhry NK (2005) Do blood tests cause anemia in hospitalized patients? The effect of diagnostic phlebotomy on hemoglobin and hematocrit levels. J Gen Int Med 20(6): 520-524.

- Chant C, Wilson G, Friedrich JO (2006) Anemia, transfusion, and phlebotomy practices in critically ill patients with prolonged intensive care unit length of stay: A cohort study. Crit Care 10(5): R140.

- Napolitano LM, Kurek S, Luchette FA, Corwin HL, Barie PS, et al. (2009) Clinical practice guideline: Red blood cell transfusion in adult trauma and critical care. Crit Care Med 37(12): 3124-3157.

- Humble RM, Hermann GH, and Krasowski MD (2017) The “rainbow” of extra blood tubes--useful or wasteful practice? JAMA Intern Med 177(1): 128-129.

- Iwen PC, Stiles KL, and Pentella MA (2020) Safety considerations in the laboratory testing of specimens suspected or known to contain the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2(SARS-CoV-2). Am J Clin Pathol 153(5): 567-570.

- Koch C, Li L, Sun Z, Hixson ED, Tang A, et al. (2013) Hospital-acquired anemia: Prevalence, outcomes, and healthcare implications. J Hosp Med 8(9): 506-512.

- Mursallana KM, Tamim HM, Richards T, Spahn DR, Rosendaal FR, et al. (2011) Preoperative anaemia and post operative outcomes in non-cardiac surgery: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet 378(9800): 1396-1407.

- Beattie WS, Karkouti K, Wijeysundera DN, Tait G (2009) Risk associated with preoperative anemia in non-cardiac surgery: A single-center cohort study. Anesthesiology 110(3): 574-581.

- Munoz M, Acheson AG, Aurbach M, Besser M, Habler O, et al. (2017) International consensus on peri-operative anemia and iron deficiency. Anaesthesia 72: 233-247.

- Becker J and Shaz B (2011) Guidelines for patient blood management and blood utilization. Bethesda (MD): AABB.

- Lin DM, Lin ES, and Tran MH (2013) Efficacy and safety of erythropoietin and intravenous iron in perioperative blood management: a systematic review. Transfus Med Rev 27(4): 221-234.

- Friedman AJ, Chen Z, Ford P, Johnson CA, Lopez AM, et al. (2012) Iron deficiency anemia in women across the life span. J Womens Health 21(12): 1282-1289.

- Auerbach M and Iain Ml (2017) The available intravenous iron formulations: History, efficacy, and toxicology. Hemodial Int 21(suppy 1): S83-S92.

- Chang L, Yan Y, and Wang L (2020) Coronavirus disease 2019: Coronaviruses and blood safety. Transfus Med Rev 34(2): 75-80.

- Shander A, Hardy JF, Ozawa S, Farmer SL, Hofmann A, et al. (2022) A global definition of patient blood management. Anesthesia & Analgesia 135(3): 476-488.

© 2022 Mathur G. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)