- Submissions

Full Text

Open Journal of Cardiology & Heart Diseases

Distal Renal Tubular Acidosis Presenting as Stridor

Khan UH, Purra S*, Rather BA, Qadri SM, Jan RA, Shah S and Koul P

Department of Internal Medicine SKIMS, Jammu and Kashmir, India

*Corresponding author: Purra S, Department of Internal Medicine SKIMS, Jammu and Kashmir, India

Submission: February 10, 2022;Published: March 31, 2022

ISSN 2578-0204Volume3 Issue4

Abstract

Chronic vitamin D deficiency when accompanied by renal tubular acidosis can cause several electrolyte imbalances that may present with weakness, pain and very rarely as tracheomalacia. Whereas Vitamin D deficiency has been documented as a cause of osteomalacia in literature, distal RTA or type 1 can only rarely present with disorders of bone metabolism. We herein report case of a 40 year old male patient who presented to us with respiratory failure and was found to have hypokalemia, hypocalcemia, hypophosphatemia, metabolic acidosis, azotemia and short stature. A careful and detailed review of his history, repeat physical examinations, laboratory data evaluation, and diagnostic testing solved the mysteries; he had intermittently received multiple doses of parentral Vitamin D(6 lac units) over past several months , but had persistent symptoms. We conclude that he had distal RTA and masked Vitamin D deficiency presenting as weakness, short stature, bone pains and tracheomalacia-causing his stridor.

Keywords:Renal tubular acidosis; Osteomalacia; Growth retardation; Tracheomalacia

Introduction

Osteomalacia is the softening of the bones due to defective mineralization of newly formed osteoid. The etiology of osteomalacia is varied and causes include Vitamin D deficiency and resistance, hypophosphatemia, renal tubular acidosis, use of mineralization inhibitors like bisphosphonates, aluminium, fluoride etc., genetic disorders like hypophospatasia, fibrogenesis imperfecta and nutritional deficiency [1]. Patients with osteomalacia may complain of bone pain and tenderness, muscle weakness, waddling gait and skeletal deformities like pigeon chest, spinal curvature and pseudofractures [2,3]. RTA type 2 is often associated with osteomalacia and rickets due to proximal phosphate wasting, increased calcium loss due to the metabolic acidosis, and secondary hyperparathyroidism leading to decreased bone mineralization [4]. The association of distal RTA with osteomalacia is very rare and controversial and only few case reports are available mentioning the association. Simultaneous occurrence of vitamin D deficiency and RTA causing osteomalacia is very rare, but not implausible [5-10]. Failure to recognize the association can lead to missed diagnoses, increased healthcare costs, and increased morbidity and mortality [11].

Case Report

A 40 year old male, chronic smoker, farmer by occupation, being treated for COPD with short acting beta agonists was admitted in emergency with complains of cough, severe breathlessness and stridor. On reception he had a pulse of 118, respiratory rate of 42, audible wheeze and stridor with blood pressure of 110/70mmHg. In view of impending respiratory failure, patient had to be intubated and was shifted to ICU. His attendant gave history of ingestion of peanuts by the patient due to which his breathlesness and stridor were attributed to anaphylactic reaction due to ingestion of peanuts (revealed on history). On further probing, patient gave history of recurrent episodes of brassy cough, stridor and breathlessness off and on for past many years. His other significant history included numbness of extremeties, fatigue, bone pains, muscle spasms and short sightedness. His anthropometry revealed body weight of 42kg (< 5 percentile), height-148cm (-2.3 SD from average), BMI of 19.17kg/ m2 equal upper and lower segment-74cm, arm span-150cm. Chest examination revealed bilateral crepitations with stridor. Cardiovascular and abdominal examination was unremarkable and neurological assessment revealed a positive Grover’s sign.

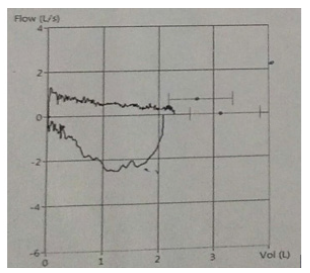

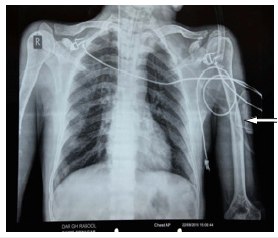

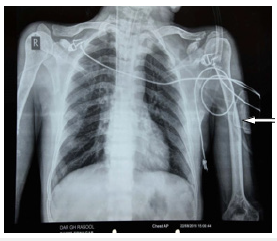

Investigations revealed haemoglobin of 12.6g/dl, with a total leucocyte count of 16x109 cells/mm3, 90% of which were neutrophils and a normal thrombocyte count of 1.5 x106. His ESR was 12 and CRP was >6. His biochemistry revealed azotemia (serum creatinine 1.99,2.04,2.3,1.56), hypocalcemia (7.86,7.73,8.15), hypophosphatemia (2.13,1.05,1.85), hypokalemia (3,2.7,2.9,3.1), high ALP-(195,205 IU/l) and a normal lipid profile. He had a partially compensated metabolic acidosis with pH of 7.25; plasma HCO3- of 16.5; pco2 of 23 and pO2 of 56, with a corresponding urine pH of 6.2. His CPK was 83 and LDH was high (508). His intact PTH was high (374.2, 246pg/ml), 25(OH)D (41,46g/ml) and 1,25(OH) D (96.10pmol/l) were normal with a low 24hr urinary calcium of 85.5mg/day. Vasculitis profile and CTD profile were negative, serum anti Ro and anti La antibodies were negative, and 24-hour urinary protein was normal (100mg/24hrs). He had an ejection fraction of 68%, concentric LVH, grade 1 diastolic dysfunction with sclerotic aortic valve on transthoracic echocardiography. Pure tone audiometry was normal and ophthalmological assessment revealed hypermetropia. HRCT of the chest revealed a thick walled trachea and peripheral bronchus with marked terminal narrowing. Expiratory scan demonstrated marked collapse with tracheal diameter of 3.4 mm. Inspiratory phase maximum tracheal diameter was 11.6mm in coronal section and 12.6mm in AP view with I:E ratio-4:1. Pulmonary Function Test (PFT) revealed an FEV1/ FVC ratio of 0.4, FEV1 of 20% and a loop suggestive of dynamic intra-thoracic obstruction (Figure 1a). Radiography of long bones revealed osteopenia, bowing of long bones and presence of faint loser’s zones (Figures 1,2 & 3). Bone densitometry revealed a Z-score of less than-2.5 SD suggesting osteoporosis. Ultrasound of abdomen showed small sized kidneys (right-8x 2.4, left kidney- 7.6x3cm), with altered echo pattern and CMD without any stones or nephrocalcinosis. In view of intermittent episodes of breathlesness and stridor, multiple possibilities like COPD, inflammatory conditions like relapsing polychondritis, congenital anomalies like presence of vascular rings, malignancy, and idiopathic conditions like Mouiner-Kuhn syndrome, Kenne Caffey’s syndrome etc.. were considered, but no single diagnosis could explain his illness.

He had intermittently received multiple doses of parentral Vitamin D (6 lac units) over past several months and no plausible cause could be ascertained to explain his biochemistry which was otherwise suggestive of vitamin D deficiency and RTA-type I. Osteomalacia was suspected, which was confirmed by elevated serum PTH level (259.8pg/mL) low serum calcium and phosphorus levels and elevated ALP. However, his vitamin D levels were normal which can be explained by the fact that he had recently received multiple doses of parentral vitamin D. Distal RTA was suspected as the patient’s urine was alkaline in presence of metabolic acidosis. In addition, he had hypokalemia and there was no evidence of protein urea or glucosuria. Considering distal RTA as one of the rare causes of osteomalacia, and short stature, azotemia and vitamin D deficiency being manifestations of this disease, we diagnosed this patient as a case of distal RTA with masked Vitamin D deficiency presenting as respiratory failure due to tracheomalacia caused by demineralization of tracheal cartilage. He was started on sodium bicarbonate 500mg tablets thrice daily with vitamin D3 of 60,000IU weekly for 1 month and calcium carbonate of 500mg twice daily.

Figure 1:Severe osteopenia of knee joint.

Figure 1a:Loop curve revealing dynamic intrathoracic obstruction.

Discussion

Although osteomalacia is common in proximal renal tubular acidosis, it can occur in distal renal tubular acidosis as well though not common. In the current case, stridor due to tracheomalacia, weakness and bone pain was secondary to osteomalacia. We consider osteomalacia in this patient to be multifactorial, both due to distal RTA and Vitamin D deficiency. Stridor is a harsh, high-pitched wheezing or vibrating sound that results from turbulent airflow in the upper airways and results from a narrowing of a central airway or the larynx caused by a foreign body, a tumor, infection, or edema. Stridor is a common respiratory symptom associated with upper respiratory diseases, yet it’s relation with hypocalcemia is not widely appreciated. Hypocalcemia, as a cause of stridor in medical literature is sparce and only 13 cases have been reported so far: four from each of USA, and UK, two from each of Spain and India, and one from Taiwan [12]. Vitamin D deficiency causes a reduction in serum calcium, which stimulates the production of extra PTH to mobilize and maintain calcium from bone and cartilage for more vital cells of the body, brain, heart and blood [13].

Figure 2:X ray revealing bowing and severe osteopenia of humerus.

Figure 3:Faint loser’s zone.

In this case, patient also had hypokalemia with a high urinary pH, despite having low plasma bicarbonate, indicated the existence of distal RTA. Renal Tubular Acidosis type I is caused by impaired distal acidification and is characterized by inability to lower urinary pH maximally (pH <5.5) under the stimulus of systemic acidemia. In general, HCO3- reabsorption is quantitatively normal [3]. Ca excretion is usually increased in distal RTA leading to rickets in children and osteomalacia in adults. Contrary to this, our patient had hypocalciuria which was due to vitamin D supplementation which he has been receiving from past one month leading to decreased excretion of calcium in the urine. In most cases, type 1 RTA develops secondary to systemic disorders like Sjögren’s syndrome, chronic active hepatitis or Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) and hypergammaglobulinemia, but it can be sporadic or familial (inherited as autosomal dominant, X-linked or recessive condition) as well. The present case can be considered as a sporadic cause of distal RTA, since other possible causes such as urological/liver disorder, autoimmune disorder (as ANA, SSA and SSB were negative), drugs, toxins and rhabdomyolysis were absent. Distal RTA or RTA type 1 can induce osteomalacia, although not as common as proximal RTA or RTA type 2 [4,12]. A plausible explanation could be that there is an increased calcium phosphate release from bone as a result of buffering effect of bone in excess acidic condition. Besides, there is also reduction in tubular calcium reabsorption secondary to chronic acidosis and secondary hyperparathyroidism which increases renal phosphate excretion and leads to hypophosphatemia due to the ability of parathyroid hormone in inhibiting proximal renal tubule phosphate transport.

There is a study published in 2004 by Domronkitchaiporn et al. [14], which compared the bone histomorphometry in patients with Distal Renal Tubular Acidosis (dRTA) to healthy subjects and showed decreased bone formation rate in patients which improved significantly after alkaline therapy. They demonstrated that metabolic acidosis per se, through its effect on osteoclasts and to a lesser extent on osteoblasts, may result in an alteration in the production of various noncollagenous proteins. On treatment of metabolic acidosis with alkali therapy not only did the bone histomorphometry improve significantly, the osteoblastic as well as osteoclastic activity was also suppressed [14]. We conclude that it is imperative to identify association of RTA and vitamin D deficiency as a cause of osteomalacia in such patients because only vitamin D supplementation with calcium may not be sufficient to improve their bone mineralization. Metabolic acidosis needs to be corrected with regular sodium bicarbonate in addition to recommended vitamin D supplementation to ascertain full recovery in such patients. This case was presented as “a weekly case presentations at Sheri-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences.” No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported. Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article.

References

- Uday S, Högler W (2017) Nutritional rickets and osteomalacia in the twenty-first century: Revised concepts, public health, and prevention strategies. Curr Osteoporos Rep 15(4):293-302.

- Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Jameson JL, et al. (2013) Manual of medicine. (18th edn), McGraw Hill, United States.

- Fukumoto S, Ozono K, Michigami T, Minagawa M, Okazaki R, et al. (2015) Pathogenesis and diagnostic criteria for rickets and osteomalacia-proposal by an expert panel suppported by ministry of health, labour and welfare, Japan, the Japanese society for bone and mineral research and the Japan endocrine society. Endocr J 62(8): 665-671.

- Brenner RJ, Spring DB, Sebastian A, McSherry EM, Genant HK, et al. (1982) Incidence of radiographically evident bone disease, nephrocalcinosis, and nephrolithiasis in various types of renal tubular acidosis. N Engl J Med 307(4): 217-221.

- Clarke BL, Wynne AG, Wilson DM, Fitzpatrick LA (1995) Osteomalacia associated with adult Fanconi’s syndrome: Clinical and diagnostic features. Clinical Endocrinol (Oxf) 43(4): 479-490.

- Taylor HC, Elbadawy EH (2006) Renal tubular acidosis type 2 with fanconi’s syndome, osteomalacia, osteoporosis, and secondary hyperaldosteronism in an adult consequent to vitamin D and calcium deficiency: Effect of vitamin D and calcium citrate therapy. Endocr Pract 12(5): 559-567.

- Ali Y, Parekh A, Baig M, Ali T, Rafiq T (2014) Renal tubular acidosis type II associated with vitamin D deficiency presenting as chronic weakness. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab 5(4): 86-89.

- Lee JH, Park JH, Ha TS, Han HS (2013) Refractory rickets caused by mild distal renal tubular acidosis. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 18(3): 152-155.

- Haridas V, Haridas K, Mudrabettu C (2017) Case studies: Renal tubular acidosis presenting as osteomalacia. Internet Journal of Rheumatology an Clinical Immunology 5(1): CS2.

- Tahir M, Ansari JK (2009) Osteomalacia due to type-1 renal tubular acidosis in a middle aged Pakistani woman. PAFMI 59(1): 123-125.

- Bohl A, Phelan E, Fishman P, Harris J (2012) How are the costs of care for medical falls distributed? The costs of medical falls by component of cost, timing, and injury severity. Gerontologist 52(5): 664-675.

- Fulop M, Mackay M (2004) Renal tubular acidosis, sjögren syndrome and bone disease. Arch Intern Med 164(8): 905-909.

- Elidrissy ATH, Babekir JS (2017) Hypocalcemic rachitic stridor: A neglected warning sign in infants. Glob J Rare Dis 2(1): 011-014.

- Domrongkitchaiporn S, Pongsakul C, Stitchantrakul W, Sirikulchayanonta V, Ongphiphadhanakul B, et al. (2001) Bone mineral density and histology in distal renal tubular acidosis. Kidney Int 59(3): 1086-1093.

© 2022 Purra S. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)