- Submissions

Full Text

Open Access Biostatistics & Bioinformatics

Modeling of Capture Fisheries and Effectiveness of the Current Gear Restriction: The Case of Lake Tana, Ethiopia

Erkie A* and Gregory H

Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, University of Pretoria, South Africa

*Corresponding author: Erkie Asmare, Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, University of Pretoria, South Africa

Submission: February 07, 2020;Published: March 12, 2020

ISSN: 2578-0247 Volume2 Issue5

Abstract

Following the exponentially increased demand for fishes, magnificent number of individuals are participated in various stages of capture fisheries in order to improve their livelihood. However, in Lake Tana fisheries, regulations related to gear restriction (fishing net and mesh size), destructive way of fishing, closing of spawning season and site, and amount of harvest are a loosely (almost not) regulated. This is attributed to weak institutions that have no incentives for fishers to manage efficiently in a way that maximized their present and future benefits. As a management framework, fishing gear restriction reduces the burden on the open access fishery and endangered species. On the other hand, ITQs encourage increased responsibility and accountability by quota owners for management and enhancement of the fishery resource. In this regard, ITQs is more efficient than gear restriction because of it creates sense of ownership and its flexibility in providing stable and profitable market.

Introduction

Ethiopia has abundant freshwater bodies with a potential of 51,500 tons of fish per a year [1]. More importantly, catches from capture fishery serve as a substitute for the expensive beef and has significant role for domestic consumption as a means of affordable nutrition and income. In addition, the role of fisheries in Ethiopia is more significant for poor, landless and jobless individuals than the rich [2,3]. Until the last two decades, most of the fishery sites in Lake Tana were untouched and fishing practices were mostly for home consumption [4]. During this time, demand for fish and its price were very cheap. Moreover, the numbers of individuals that involve in various stage of fishery were also very small. However, rapid population growth, unemployment and shortage of agricultural land caused for increased reliance on communal and open access capture fisheries to satisfy daily basic needs [5]. Besides, high inflation and increased price for other meat sources like beef and chicken caused exponential increase in demand for fish and fishing. Gordon A et al. [6] also estimated aggregated demand growth for fish in Ethiopia to be 44% over ten years. This increased demand for fishes caused fishing practice to increase exponentially. In this regard, more than 40,000 individuals are participated in various stages of capture fisheries in order to improve their livelihood [7].

Statement of the Problem

Lake Tana fishery is no one’s property, which everybody can access for fishing but with no spirit of ownership among users. Hence, each fishers act in his or her own self-interest in order to maximize their own private profit. These gives incentive for both artisanal and commercial fishers to overexploit the fishery resources without any restriction (Alayu, 2012). This over competition and pressure put the capture fisheries under big threat of over exploitation even up to fishing fishes that don’t reached table size or maturity [1]. Besides the above listed factors, over population accompanied by overfishing, pollution form points and nonpoint sources, wetland and their buffer zone degradation, recession farming and weak enforcement of fisheries regulations play the main role for the degradation of capture fishery [1,4]. Currently, fishing at Lake Tana is non-excludable but rival.

Besides its openness to all, regulations related to gear restriction (fishing net and mesh size), destructive way of fishing, closing of spawning season and site, and amount of harvest are a loosely (almost not) regulated. The consequence of such relentless harvest and over competition will undoubtly be the Hardin’s “tragedy of the commons”. A study by Eshete [4] also confirmed that in this Lake, catch per unit of effort for the three main commercially important fish species become alarmingly declined. According to this author, the catch was 177kg/trip/boat in 1993, after eight years (2001) it became 140kg/trip, and disappointingly, in 2010 the catch declined to 56kg/trip/boat. Consequently, such unlimited competition leads to unsustainable resource extraction on the expense of future generation. Such overexploitation appeared because of the weak institutions could not allow or have no incentives for fishers to manage efficiently in a way that maximized their present and future benefits. However, to design efficient institutions it requires understanding of effectiveness of different fishery management instruments and dynamic fishery. Therefore, this policy brief tries to give some insight about the optimal way of extraction and regulation of such fishery resource.

Management of Lake Tana Capture Fishery

Open access capture fisheries of lake Tana

Lake Tana, which is the third largest Lake in Africa, gives direct and indirect services for about 2 million peoples in its catchment and surrounding wetlands [5]. Fisheries of Lake Tana is no one’s property, it is open access to everybody. These individuals can fish in a way that they like without any restriction and caring about its sustainability. Fisheries of this Lake faces two contradictory things. The first is its non-excludability and the second its rivalry. In this case, being altruistic to conserve this resource is not a rational decision for fishers because many other free riders will exploit it today. Each fishers act in his or her own self-interest in order to maximize their own private profit by choosing variable inputs like a single season and ignoring the future. Therefore, if the fishery resource is openly accessible to everyone, no one has an incentive to invest on it in order to improvement its state (Ostrom, 2000). Hence, the existence of such strong temptation to free ride on the expense of others will lead to inefficient way of fishing. The main contributor for this overexploitation is ineffectiveness of fishery related institutions for managing them.

Modeling of an open-access fishery

In open access case, fishers have not the power to control over the biomass. Therefore, profit maximization and available biomass is contingent on the decision or harvest level of the previous season. Under this condition, the biomass of fish available for next season depends on the level of harvest of the current users so it may crash or reached steady state. In addition, in open access fishery there is no owner who collect rent and producers behave as the price of biomass is zero.

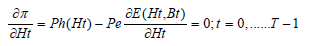

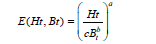

Unlike optimally managed fishery, open access fishery has no marginal user costs. Therefore, the first order condition for open access will be:

Modeling of the current policy of gear restrictions

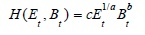

This method is one way of policy instrument in fishery sector with the intension of reducing over harvest by using advanced fishing boats and destructive fishing nets like using mesh size below 8cm and using poisoning plant species as fishing tool. The fish production or harvest function can be derived from cobb- Douglas production function.

The coefficient, c, is catchability coefficient and 1/a and b are elasticities. By rearranging the above harvest function, the effort function can be derived as:

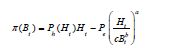

The above effort function indicates that as harvest increase and biomass decrease the effort require become increased. However, when the biomass increased the required effort become small because of fishes can easily captured. The main aim of gear restriction is to reduce catchability of fishes. This decrease in catchability increased the effort required for fishing. Hence, this is one method of reducing overfishing by raising cost of fishing and reduces the rate of catch of fishers. This helps to balances biomass of fishes and its future availability. In open access each fisher has the intention to cash more fish to maximize their profit without thinking about future hence caused for fishery depletion. However, using gear restriction as a policy instrument reduces the amount of catch by reducing the catchability rate and restricting the type of fishing gear to be used like prohibiting small mesh sized gillnet and monofilament gillnet. Under gear restriction, the profit function can be formulated as:

Model an optimally managed Fishery

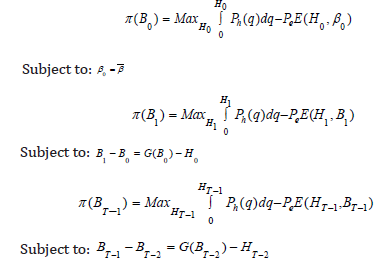

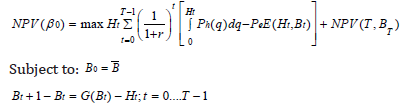

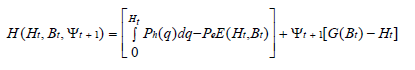

Optimal management maximizes the net present value (NPV) by choosing to harvest at each period. Therefore, the model for optimally managed fishery can be specified as:

Subject to: HT = G(BT ) To derive optimality conditions, the Lagrangian can be formulated as:

NPV is the net present value of benefits above costs from the fishery, β is the biomass or stock of fish, H is the harvest, E is the effort function, which depends upon harvest and biomass, G is a growth function, which depends on the biomass, Ph is the demand curve for fish in the market and t is time measured as fishing seasons. The biomass begins at an initial biomass and evolves over time depending upon growth and harvest.

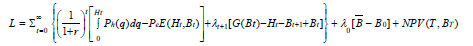

To derive the welfare created for the society by the decision of a generation and interpret it we construct Current-Value or Undiscounted Hamiltonian during transition as followed:

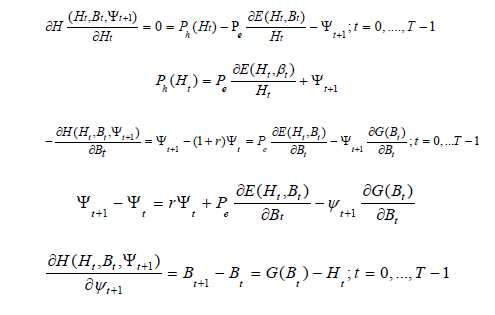

First Order condition for undiscounted Hamiltonian

Evaluation of effectiveness of gear restriction

Fishing gear restrictions is among the commonly used tool for fishery management. This method forbids the use of the most efficient equipment. It also used to catch fishes selectively either by size or species. Fishing gear restriction play important role to avoid overfishing and facilitate the preservation and regeneration process. This restriction may require some fishers to adopt new technology and those who could not successfully compete under new technology or restriction will excluded themselves from competition. Hence, this fishing gear restriction reduces the burden on the open access fishery and the endangered species. However, fishing gear restriction do not address problem of open access and are certainly not the optimal regulatory instrument for enhancing economic efficiency. Again, those who fulfill the restriction criteria can harvest as they like, hence problems raised from open access may not eliminate in this method. Under some conditions, they may produce net economic benefits, but net losses may also result. Hence, regulation of fishing activity through fishing gear restrictions may not better method for improving economic efficiency in a fishery [8].

Evaluation the effectiveness of ITQs implementation

ITQs it is a right–based allocation or privilege to a certain amount of quota to individuals. It addresses problem of open access by creating owner of the quota or owner of the fish, which is enforceable. In addition, the quota can properly price in order to transfer or sale to others. Therefore, fishers could trade among themselves and fishers who might want to enter the market would have to purchase the quotas from existing fishers. Competition among the potential purchasers would drive up the price of the transferable quotas until it reflected the true market value of future rents. This method produces more cost-effective outcomes than the traditional restrictions [9]. Transferability in ITQs shows fishers or ITQ owners can sell or buy their ITQ or lease their quota depending on how much they want to participate in the fishery.

Such ITQs to catch the share of the total allowable catch of fish each year aimed to reduce overcapitalization, promote conservation of stocks, improve market conditions, and promote safety in the fishing fleet. ITQ method is very important for fishery management to reduce over competition and give flexibility for fishers over the rate and timing of their fishing. It also improves the overall economic efficiency of the commercial fishing. ITQs play a pivotal role to provide stable and profitable market and social benefits from controlling overcapitalization [10]. ITQs generally halt and often reverse stock declines because fishers’ have incentives to enhance stocks (resource stewardship). ITQs increases the efficiency of fishers because quotas can be traded and end up in the hands of the most efficient boat owners and resulting in fewer boats. This decrease in number of boats and labor cost increases catches per boat and profit. However, ITQs ignore the critical problem of gear selectivity. Again, for ITQs to be effective, it needs to set the proper quota but there is problem in setting TACs [11].

Conclusion

Even though the contribution of Lake Tana fishery is extremely high for both smallholders and commercial fishers, lack of property right and loosen regulation makes the fishery resource under threat. In addition, the non-excludability and rivalry nature of the resource aggravates the competition and illegal way of fishing. In this Lake, most of fishery regulations give emphasis for fishing gear restriction but the implementation of this instrument even with its limitations is almost zero. Despite the fact that fishing gear restriction has some advantages, it is not better method for improving economic efficiency in the fishery. ITQs encourage increased responsibility and accountability by quota owners for management and enhancement of the fishery resource. In this regard, ITQs is more efficient than gear restriction because of it creates sense of ownership and its flexibility in providing stable and profitable market. In addition, it has pivotal social benefits by controlling overcapitalization.

Recommendations

To sustain the contribution of Lake Tana fishery, the following issues requires due attention:

- The first and more important thing is enforcing fishing gear restriction. This allows the fishery resource to regenerate itself by avoiding illegal and destructive way of fishing. At this time, the total stock of fish in Lake Tana fishery is not well known, fishers have no license and fish with small mesh sized and illegal gillnet. Under these conditions, application of ITQ is difficult to set total allowable catch (TAC) so gear restriction is more compatible for the study area.

- Strong enforcement on the type of gear to be used and use fishing license so it serves as a means of exclusion and closing season for regeneration and fishing license

- Restrict the numbers of fishers and harvest at each year to the optimal level of harvest

- Promoting and strengthening culture fishery also reduces burdens on capture fishery.

- Furthermore, use catch quota of commercial fishers and other means of internalizing externality posed by rich and greedy fishers.

- ITQ is efficient method for the sustainability of Lake Tana therefore, there must be strong effort on studying the current stock of fish, numbers of legal and illegal fishers to set TAC.

References

- Agumassie T (2018) Review in current problems of Ethiopian fishery: in case of human and natural associated impacts on water bodies. International Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Studies 6(2): 94-99.

- Erkie A (2017) Current trend of water hyacinth expansion and its consequence on the fisheries around north eastern part of lake Tana, Ethiopia. Journal of Biodiversity & Endangered 5(2): 2-5.

- Erkie A, Sewmehon D, Dereje T (2016) Fisheries of Jemma and Wonchit rivers: as a means of livelihood diversification and its challenges in north Shewa zone, Ethiopia. Fisheries and Aquaculture Journal 7(4): 1-7.

- Erkie A, Sewmehon D, Dereje T, Mihret E (2016) Impact of climate change and anthropogenic activities on livelihood of fishing community around Lake Tana, Ethiopia. EC Agriculture 3(1): 548-557.

- Eshete D, Wassie A, Vijverberg J (2017) The Decline of the lake tana (Ethiopia) fisheries: causes and possible solutions. Land Degrad Develop 28(6): 1842-1851.

- Anderson EE (1988) Factors affecting welfare gains from fishing gear restrictions. NJARE pp. 156-166.

- Dagninet A, Mihret E, Tegegne D, Ayalew D, Kiber T, et al. (2018) Fishing condition and fishers’ income: the case of lake tana, Ethiopia. Int J Aquac Fish Sci 4(1): 6-9.

- Gordon A, Sewmehon D, Melaku T (2007) Marketing systems for fish from lake tana, Ethiopia: opportunities for marketing and livelihoods. IPMS Nairobi, Kenya, Africa.

- Acheson J, Apollonio S, Wilson J (2015) Individual transferable quotas and conservation: a critical assessment. Ecology and Society 20(4): 1-7.

- Buck EH (1995) Individual Transferable Quotas in Fishery Management. NLE 1-20.

- Tietenberg T, Lewis L (2012) Environmental and Natural Resource Economics (9th Edition). Pearson Education, London, United Kingdom.

© 2020 Erkie A. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)