- Submissions

Full Text

Novel Techniques in Nutrition and Food Science

Prevalence and Socio Demographic Determinants of Underweight Among Men and Women Aged 15-49 Years in Ethiopia

Eleni Tesfaye Tegegne1, Kaleab Tesfaye Tegegne2*, Mekibib Kassa Tessema3 and Abiyu Ayalew Assefa2

1University of Gondar, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, School of Nursing, Gondar, Ethiopia

2Department of Public Health, Hawassa College of Health Science, Hawassa, Ethiopia

3Leishmania Research and Treatment Center, University of Gondar, Gondar, Ethiopia.

*Corresponding author: Kaleab Tesfaye Tegegne, Hawassa College of Health Science, Department of Public Health, Hawassa , Ethiopia

Submission: February 05, 2021;Published: March 04, 2021

ISSN:2640-9208Volume5 Issue4

Abstract

Background: According to recent data from the Ethiopian demographic and health survey (EDHS), national prevalence of underweight among men and women aged 15-49 years is 27%.

This study aims to: (1) assess the prevalence of underweight (2) describe variations in underweight by socio demographic factors age, wealth, residence, and education etc. in Ethiopia. Methods: The present study was performed using the EDHS 2016 dataset. Socio demographic variables were selected based on their availability in the dataset Nutritional status of men and women age 15-49 years measured by their BMI cut-off point of 18.5 kg/m2 is used to define underweight. Descriptive statistics were employed to show the distribution of socio-demographic characteristics. Complementary log log regression model used to determine the true association between underweight and basic socio-demographic factors.

Results: Of the total sample of 27289 of men and women age 15-49 years at the time of survey, 27 % (n = 6645) have underweight in Ethiopia, with underweight mainly concentrated among adolescent (57.96%). About 61 % of the variation in the outcome variable (underweight) is explained by the independent variables included in model. Men and women in the 15-19 age group (ARR=4.882, 95% CI 4.516-- 5.278) and Men and women age 15-49 years in urban areas (ARR=1.650, 95% CI 1.494-- 1.822) were found to be major contributing factors to the under weight

Conclusion: There was a high prevalence of underweight among men and women age 15-49 in Ethiopia Age and residence are socio demographic factors that show a statistical significant association with underweight among Men and Women age 15-49 in Ethiopia It is important to target adolescent and urban areas during implementing nutritional interventions in Ethiopia.

Keywords: Underweight; Socio demographic; EDHS; Ethiopia

Abbreviations: ARR: Adjusted Relative Risk; BMI: Body Mass Index; CED: Chronic Energy Deficiency; CI: Confidence Interval; COR: Crude Odd Ratio; DHS: Demographic Health Survey; EDHS: Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey; ICF: Inner City Fund; SNNPR: Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples Region; WHO: World Health Organization.

Background

In 2014, WHO estimated that around 462 million adults were underweight (18 years or

older) [1]. Some evidence in developing countries indicate that malnourished individuals, that

is, women with a body mass index (BMI) below 18.5, show a progressive increase in mortality

rates as well as increased risk of illness [2]. Women who receive even a minimal education are

generally more aware than those who have no education of how to utilize available resources

for the improvement of their own nutritional status and that of their families. Education may

enable women to make independent decisions, to be accepted by other household members,

and to have greater access to household resources that are important to nutritional status

[3]. A comparative study on maternal nutritional status in 16 of the 18 DHS studied countries

[4] and a study in the SNNPR of Ethiopia [5] showed that rural women are more likely to suffer from chronic energy deficiency than women in urban areas.

These higher rates of rural malnutrition were also reported by local

studies in Ethiopia [6,7]. Similarly, studies on child nutrition [8,9]

also showed significantly higher levels of stunting among rural than

urban children.

Women’s age and parity are important factors that affect

maternal depletion, especially in high fertility countries [6]. DHS

surveys conducted in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Malawi, Namibia, Niger,

Senegal, and Zambia show a greater proportion of mothers aged

15-19 and 40-49 that exhibit chronic energy deficiencies (CED).

A local study in Ethiopia also showed that women in the youngest

age group (15-19) and women in the oldest age group surveyed

(45-49) are the most affected by undernutrition [5]. Findings of

the 2000 Ethiopia DHS [10]. Showed that 25 percent of women in

the reproductive age group (15-49 years) fall below the cutoff of

18.5, indicating that the level of chronic energy deficiency (CED) is

relatively high in Ethiopia. This also indicates that the prevalence of

undernutrition in Ethiopia is about 1.5 times greater than the Sub

Saharan average prevalence of 20 percent during the period 1980-

1990 [11]. In adolescence, a young woman’s nutritional needs

increase because of the spurt of growth that accompanies puberty

and the increased demand for iron that is associated with the onset

of menstruation [12].

Data on nutrition coverage is limited yet; the lack of nationally

representative data on status of underweight among men and

women aged 15-49 impedes countries ability to guide policy and

programs. To address this gap, we used Demographic and Health

Survey (DHS) data to describe the status of underweight using BMI

among men and women aged 15-49 at the country levels.

The objectives are to:

a. assess the prevalence of underweight.

b. describe variations in underweight by socio demographic

factors age, wealth, residence, and education etc.

This study is intended to provide policymakers and program

implementers with information on the state of underweight and its

socio demographic determinants among men and women aged 15-

49 at country level.

Method

Data and Variables

The data used in this study were derived from the EDHS

conducted in 2016. In the EDHS 2016, a sample of 16,650

residential households was selected in two stages. Enumeration

areas were selected with probabilities proportional to size followed

by systematic sampling of households from each enumeration area

that ensured an equal probability. Interviews were completed with

a total of 15,683 women aged 15-49 years and a total of 11606

men aged 15-49 years from the selected households They were

interviewed on a range of socio-demographic and health issue [13].

In this study, the outcome variable was underweighting for men

and women aged 15-49 years (1 if the people HAVE underweight 0 otherwise). The independent variables that were selected based

on their availability in the dataset include working status in the

past 12 months, occupation status, religion, residence place,

region, sex, media exposure, marital status, age, household wealth

index, Number of living children and Literacy. Measurement of

underweight Nutritional status of men and women aged 15-49

years were assessed using BMI. The body mass index (BMI) is

expressed as the ratio of weight in kilograms to the square of height

in meters (kg/m2). Nutritional status of men and women aged 15-

49 years measured by their BMI cut-off point of 18.5kg/m2 is used

to define underweight [14].

Statistical analysis

Sampling weights provided with the EDHS dataset were used

during analysis Further details on sample weights can be found

in the EDHS report [15]. Descriptive statistics were employed

to show the distribution of socio-demographic characteristics.

Goodness of fit test that is Hosmer and Leme show test for logistic

regression model has p-value of <0.05 and this indicated that

logistics regression model has not fit for the data. The Nagelkerke

R Square shows that about 61 % of the variation in the outcome

variable (underweight) is explained by the logistic model. The

overall accuracy of the logistic model to predict subjects having

underweight (with a predicted probability of 0.5 or greater) is 84.8

% The reliability analysis showed that Cronbach’s alpha result of

the variables is 0.883 and this indicated good internal consistency

of the questionnaire.

We used Complementary log regression model to determine the

true association between underweight and basic socio-demographic

factors because the diagnostic test of logistic regression model

that is goodness of fit of the model by the Hosmer and Leme show

test failed ; (where p-value of <0.05 was found) and there is large

difference between those who have the outcome(underweight ) and

those who do not have the outcome (no underweight ) All analyses

were performed using statistical software SPSS (Version 16.0).

Ethics approval

This study is a secondary analysis of publicly available dataset where permission was obtained through registering with the DHS website and therefore no ethics approval was required.

Result

Baseline characteristics

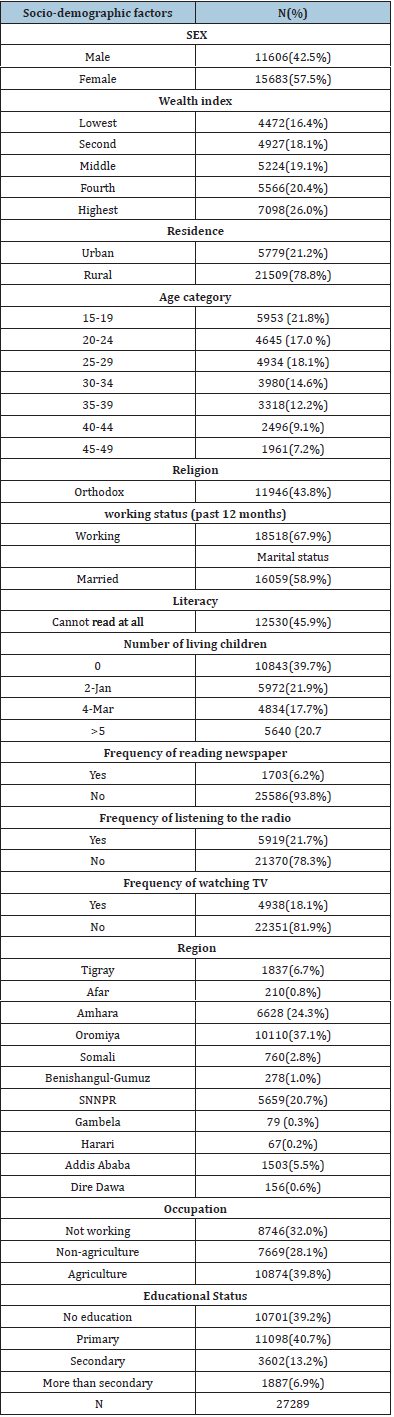

Of the total sample of 27289 of Men and Women 15-49 years at the time of survey, 27% (n = 6645) have underweight. As summarized in Table 1, A predominant percentage of the men and women 15-49 years lived in rural areas (78.8%), respondents in the regions of Oromiya were (37.1%) and Amhara (24.3%).

Table 1:Individual, household and community level characteristics of Men and Women 15-49 years, Ethiopia, 2016.

In terms of men and women 15- 49 years age, overall, 21.8% of men and women were between 15 and 19 years of age of the total only 16.4% were in lowest wealth quintile and 26.0 % were in the highest wealth quintile.

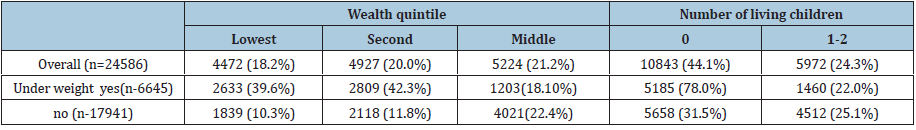

Bi-variable analysis

For every one-year increase in age odds of underweight among

men and women age 15-49 years decrease by 0.278 times (COR =

0.278; 95% CI: 0.268-- .0.288). Odds of underweight among men

and women age 15-49 years in urban areas increased by 7.448

times (COR 7.448 95% CI: 6.979, 7.949) compared to those living

in rural areas. Odds of underweight among men and women age

15-49 years in afar decreased by 0.799 times (COR 0.799; 95% CI:

0.719 -- 0.888) compared to tigray region of Ethiopia.

Odds of underweight among men and women aged 15-49 year

in Amhara decreased by 0.124 times (COR 0.124; 95% CI: 0.112 --

0.139) compared to tigray region of Ethiopia. Odds of underweight

among men and women aged 15-49 year in poorer wealth category

decreased by 0.209 times (COR 0.209 95% CI: 0.191 - 0.228)

compared to poorest wealth categories. Odds of underweight

among men and women age 15-49 year who were never married

decreased by 0.276 times (COR 0.276; 95% CI: 0.260 -- 0.293)

compared to those who are married. For everyone increase in

number of living children odds of underweight among men and

women age 15-49 year decreased by 79% (COR = 0.207; 95% CI:

0.197-- 0.219) (Table 2).

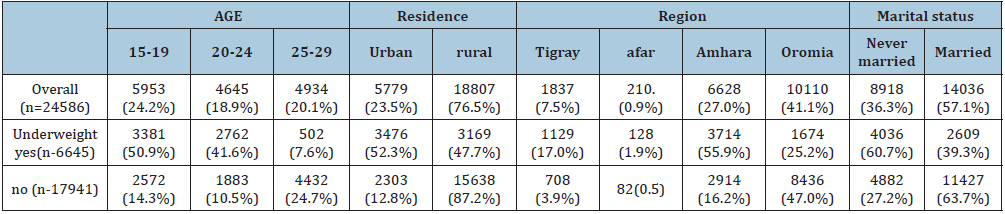

Table 2:Socio demographic characteristics of Men and Women aged 15-49 years according to underweight, Ethiopia 2016.

Complementary log log regression analysis

Men and women aged 15-49 years in urban areas are 1.65 times (ARR=1.650, 95% CI 1.494-- 1.822) more likely to develop underweight (BMI<18.5) than in rural areas. For every one-year increase in age among Men and women in the 15-49 age group, there is 4.88 times (ARR=4.882, 95% CI 4.516-- 5.278) less likely to develop underweight (BMI<18.5) (Table 3&4).

Table 3:The association between underweight (BMI<18.5kg/m2) and socio demographic characteristics of Men and Women aged 15-49 years, Ethiopia 2016.

Table 4:Socio demographic characteristics of Men and Women aged 15-49 years according to according to underweight, Ethiopia 2016.

Discussion

Prevalence rates of underweight is 6645 (27.0%) in our study which is comparable to more recent studies, 27.5% in Ethiopia, 22.7 % in rural India, 22.9% in India, 22.3% Uganda respectively [16-19] and prevalence of underweight was substantially higher than in wealthier countries [20]. In this study prevalence rates of underweight were not significantly different between women and men and this is similar with study in rural south India [17]. In this analysis Men and women in the 15-19 age group were 4.88 times (ARR=4.882, 95% CI 4.516-- 5.278) more likely to be underweight (BMI<18.5) than those aged 25-29 this finding is similar with study in Tanzania that found women aged 15-19 years, and those aged 40-49 years were more likely to be underweight than those aged 20- 29 and 30-39 years [21] and in Addis Ababa younger women aged 15-19 years were 1.79 times and 2.13 times more likely to be underweight compared to those aged 30-49 years for 2000 and 2011 years respectively [22] and study in Ethiopia indicated that the risk of underweight was on average significantly higher for younger adolescents than older adolescents [23] and study in Ethiopia age of adolescent (early age adolescent) was identified as an associated factor for adolescent underweight 16 and Increasing age had a significant inverse association with underweight among women from both regions of residence in Bangladesh [24] and correlate of underweight were young age in Addis Ababa 22 and the highest odds of underweight among the women of 15-19 years according to both Asian (AOR: 2.07, 95% CI: 2.00-2.13) and WHO (AOR: 2.58, 95% CI: 2.51-2.66) cutoffs in India [18].

In men underweight was associated with younger (15-19 years)

and older age (>55 years) (P<0.001) in Uganda [19] and contrarily

with study in the municipality of Bambuí (southeastern Brazil),

the prevalence of underweight increased with age in both genders,

reaching an odds ratio of 2.5 (95%CI: 1.5-4.0) the ≥ 80-year-old

category [25]. An association of age with BMI for Age z-score has

previously been reported [5,26].

In our study the highest prevalence rates of underweight

were observed among younger age (15-19) and this may be due

to majority (57.5%) of the respondents were female and majority

(38.83%) of the respondents were adolescent age [15-24].

Adolescent women often have no or little power in decision making

about food distribution in the household, and can be marginalized,

leading to poor nutritional status. In addition, early sexual

activity and associated health problems, such as the termination

of pregnancy and miscarriage, also endanger the nutritional

status of adolescent women [27]. Women with increasing age and

contraceptive use had higher prevalence of overweight/obesity and

a lower prevalence of underweight. Hormonal changes associated

with childbearing could cause weight gain among women [28].

Moreover, women with increasing age/pregnancy are also more likely to take hormonal contraceptives, a factor which is thought to be associated with weight gain [29]. Furthermore, advancing age is correlated with increased parity another associated factor for overweight/obesity [30]. Women usually gain weight during pregnancy, which could be sustained for a lifetime if weight loss does not occur in the post-partum period [31,32]. The positive association between age and body weight could be due to the fact that increasing age is a known associated factor of overweight as well as for other non-communicable, diseases [33]. Prevalence rate of adolescent underweight in our study is 57.96% which is higher than According to the Ethiopia Demographic Health Survey Reports (EDHS), adolescent underweight in 2000, 2005, and 2011 was 38.4, 32.5, and 36% respectively [7] and the pooled prevalence of adolescent underweight 27.5% in Ethiopia (95%CI: 17.9, 37.1) [24].

The EDHS data of 2016 show Prevalence of underweight among women is 42.4 % which is higher than 25 out of 33 countries in Sub Saharan Africa had lower underweight (14.5%) adult female populations [34] and lower compared to previous study in Ethiopia most of the underweight adolescents were females (53.20%) [23]. Men and women aged 15-49 years in urban areas are 1.65 times (ARR=1.650, 95% CI 1.494-1.822) more likely to develop underweight (BMI<18.5) than in rural areas. This may be due to Majority of 5779 (54.0%) respondents in urban areas have no education and majority of 5681 (98.3%) the respondents in urban areas are adolescence age 15-19 years and Lack of awareness among adolescent women about their own health and nutritional status is another reason why their nutritional status is poor [35]. There is faster growth and development in the early age of adolescent (10-14 years) as compared to late adolescent (15-19 years). Hence, if the requirement for achieving their maximum need for growth and development is not fulfilled, they will be prone to develop underweight [36].

Conclusion

There was a high prevalence of underweight among men and women aged 15-49 in Ethiopia. Age and residence are socio demographic factors that show a statistically significant association with underweight among men and women aged 15- 49 in Ethiopia. The study also shows the subgroups of population with higher prevalence rates of underweight that demand greater attention from the health services in terms of recovering of an adequate nutritional status. In order to improve nutritional status of population, policies should focus on nutritional intervention programs that target adolescent and urban areas.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to Measure DHS, ICF International Rockville, Maryland, USA for providing the 2016 EDHS data for this analysis.

References

- (2018) Obesity and overweight. World Health Organization.

- Rotimi C, Okosun I, Johnson L, Owoaje E, Lawoyin T, et ale (1999) The distribution and mortality impact of chronic energy deficiency among adult Nigerian men and women. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 53: 734-739.

- (1990) Women and nutrition. Nutrition Policy Discussion Paper No. 6. Administration Committee on Coordination–Sub-Committee on Nutrition (ACC/SCN).

- Loaiza, Edilberto (1997) Maternal nutritional status. DHS Comparative Studies No. 24. Macro International Inc Calverton, Maryland, USA.

- Teller H, Yimar G (2000) Levels and determinants of malnutrition in adolescent and adult women in southern Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of HealthDevelopment 14(1): 5766.

- Zerihun T, Larson CP, Hanley JA (1997) Anthropometric status of Oromo women of childbearing age in rural south-western Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Health Development 11(3): 1-7.

- Luzzi AF, Scaccini C, Taffese S, Aberra B, Demeke T (1990) Seasonal energy deficiency in Ethiopian rural women. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 44(Supp 1): 7-18.

- Sommerfelt, Elizabeth A, Kathryn S (1994) Children’s nutritional status. DHS Comparative Studies No. 12. Calverton, Maryland, USA: Macro International Inc, USA.

- Yimer G (2000) Malnutrition among children in southern Ethiopia: Levels and risk factors. Ethiopian Journal of Health Development 14(3): 283-292.

- (2005) Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2005. Central Statistical Authority. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA: CSA and ORC Macro, USA.

- Administration Committee on Coordination–Sub-Committee on Nutrition (ACC/SCN). (1992) Second report on the world nutrition situation, Vol. 1 & 2, Global and regional results. New York, USA.

- World Bank (1994) A new agenda for women’s health and nutrition. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank, USA.

- CSA and ICF (2016) Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA.

- (2000) Fourth Report on the World Nutrition Situation. Geneva: ACC/SCN in collaboration with IFPRI, USA, p. 121.

- (2012) Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Central Statistical Agency/Ethiopia and ICF International. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Berhe K, Kidanemariam A, Gebrehiwot G, Alem G (2019) Prevalence and associated factors of adolescent undernutrition in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Nutrition 5: 49.

- Little M, Humphries S, Patel K, Dewey C (2016) Factors associated with BMI, underweight, overweight, and obesity among adults in a population of rural south India: a crosssectional study. BMC Obesity 3: 12.

- Al Kibria, Swasey K, Hasan Z, Sharmeen A, Day B (2019) Prevalence and factors associated with underweight, overweight and obesity among women of reproductive age in India. Global Health Res Policy 4: 24.

- Schramm S, Kaducu FO, Smedemark S, Ovuga E, Sodemann M (2016) Gender and age disparities in adult under nutrition in northern Uganda: high-risk groups not targeted by food aid programmes. Trop Med Int Health 21(6): 807-817.

- Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, Thomson B, Graetz N, et al. (2014) Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980-2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet 384: 766-781.

- Mtumwa A, Paul BA (2016) Determinants of undernutrition among women of reproductive age in Tanzania mainland. S Afr J Clin Nutr 29(2): 75-81.

- Tebekaw Y, Teller C, Ramos U (2014) The burden of underweight and overweight among women in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 14: 1126.

- Assefa H, Belachew T, Negash L (2015) Socio-demographic factors associated with underweight and stunting among adolescents in Ethiopia. Pan African Medical Journal 20: 252.

- Hashan MR, Gupta RD, Day B, Gulam MK (2020) Differences in prevalence and associated factors of underweight and overweight/ obesity according to rural–urban residence strata among women of reproductive age in Bangladesh: evidence from a cross-sectional national survey. BMJ Open 10(2): e034321.

- Barreto SM, Passos VMA, Costa MFF (2003) Obesity and underweight among Brazilian elderly. The Bambuí Health and Aging Study. Cad Saude Publica 19(2): 605-612.

- Mulugeta AF, Stoecker BH, Kruseman G, Linderhof V, Abraha Z, et al. (2009) Nutritional status of adolescent girls from rural communities of Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Health Development 23(1): 5-11.

- Girma W, Genebo T (2009) Determinants of nutritional status of women and children in Ethiopia. Calverton: ORC Macro, Calverton, Maryland, USA.

- Gunderson EP (2009) Childbearing and obesity in women: weight before, during, and after pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 36(2): 317-332.

- Gallo MF, Lopez LM, Grimes DA, Carayon F, Schulz KF, et al. (2014) Combination contraceptives: effects on weight. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1):CD003987.

- Li W, Wang Y, Shen L, Song L, Li H, et al. (2016) Association between parity and obesity patterns in a middle-aged and older Chinese population: a cross-sectional analysis in the Tongji Dongfeng cohort study. Nutr Metab 13: 72.

- Bhavadharini B, Anjana RM, Deepa M, Jayashree G, Nrutya S, et al. (2017) Gestational weight gain and pregnancy outcomes in relation to body mass index in Asian Indian women. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 21(4): 588-593.

- Kominiarek MA, Peaceman AM (2017) Gestational weight gain. Am J Obstet Gynecol 217: 642-651.

- Reas DL, Nygård JF, Svensson E, Sørensen T, Sandanger I (2007) Changes in body mass index by age, gender, and socio-economic status among a cohort of Norwegian men and women (1990–2001). BMC Public Health 7: 269.

- Fogelman A (2009) The changing shape of malnutrition: obesity in sub-Saharan Africa. Boston: The Frederick S. Pardee Center for the Study of the Longer-Range Future.

- Bitew FH, Telake DS (2010) Undernutrition among women in Ethiopia. USAID.

- World Health Organization (2005) Nutrition in adolescence-issues and challenges for the Health Sector. WHO, pp. 1-123.

© 2021 Kaleab Tesfaye Tegegne. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)