- Submissions

Full Text

Novel Techniques in Nutrition and Food Science

Comparison of Vegan and Non-Vegan Diets on Memory and Sleep Quality

Pinar Sengul*

Department of Psychology, UK

*Corresponding author: Pinar Sengul, Department of Psychology, UK

Submission: August 19, 2020;Published: September 24, 2020

ISSN:2640-9208Volume5 Issue2

Abstract

Nutrition influences a wide range of physiological and cognitive mechanisms. Vegan (Plant-Based) diet is known to be associated with a healthy cardiovascular and cerebrovascular system. Studies on the Mediterranean diet have shown that diets high in fruits and vegetables are linked with better cognitive performance and lower rates of neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease. The present study assessed verbal memory and sleep quality in a cohort of sixty-two adults aged 40 and above. Participants were split into strictly defined diet categories: vegan, vegetarian, pescatarian, omnivores with low meat/fish consumption and omnivores with high meat/fish consumption, using a modified Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener questionnaire. Verbal learning memory was assessed using the California Verbal Learning Test, and sleep quality was evaluated using the Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index. Diet was found to have a significant effect on memory but no significant effect on sleep quality. The sample size, diluted by the five diet categories, may have been insufficient to capture the effects on sleep. Further research is needed to elucidate the protective role of plant-based diets on cognitive functions and sleep quality. Unlike main-stream knowledge in the relationship between memory and eating animal-based food, this research has debunked that hypothesis by showing that there are no significant relationship be-tween consuming animal products and having a better memory. Further research can even support a hypothesis that suggests that more plant-based eating habits would strengthen memory if gender is controlled with a larger sample size.

Introduction

Previous studies have indicated that the modern Western diet (high in animal fat and animal protein) is associated with raised incidences of obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, hypertension and cancer as well as mood and neurological disorders [1-5]. Evidence also exists of a correlation between macronutrient intake and the quality of sleep [6], and that reductions in sleep quality are related to lower cognitive functioning [7]. Another study [8] suggests that a vegan diet is associated with improvements in mood and neurological disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease. Studies on the effects of a Mediterranean diet [9] indicate that it is associated with improved mood and cognitive processing speeds.

There are, however, a number of conflicting findings and the levels of statistical significance of some of the results referred to above are low due to small participant numbers, short study periods and diverse nutritional patterns [10,11]. The possible implications of the effects of diet on the physical, mental and emotional health of the general population makes a controlled study of the effect of specific classified diets on defined sleep quality measures and on objectively measured memory performance highly relevant. For the present pilot study, the independent variable is diet over the last five years in five classifications: vegan, vegetarian, pescatarian, omnivore-low and omnivore-high, as established by the Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener, (MEDAS) questionnaire. The two de-pendent variables are sleep quality, self-reported on the Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index, (PSQI), and memory performance measured by the California Verbal Learning Test, 3rd Edition, (CVLT-3).

Methods

Measures

The primary measures used in the study were the California Verbal learning Test-3rd Edition, the Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener and the Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index.

CVLT-3

The CVLT-3, standard form, was used to measure memory performance. Participants were given word lists to memorize and recall was tested after a timed delay. Raw scores were standardized for age. For the current study the key outcome measure was total recall.

MEDAS

The Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener consists of 14 questions on food and drink consumption. For the present study an amended scoring system was used to categorize individuals to one of the five specified dietary groups.

PSQI

The Pittsburg Sleep Quality Questionnaire assesses sleep quality and disturbances over the previous month. It contains a list of 19 questions giving scores for sleep quality, latency, duration and efficiency and also disturbances, use of medications and dysfunctions during day-time activities.

Procedure

Once informed consent had been given by the participant and they have been given instructions to be focused as much as possible, the experimenter started the questionnaire booklet. This consisted of the CVLT test followed by the MEDAS and PSQI questionnaires. The delayed components of the CVLT were completed after the questionnaires. The entire procedure took between 40 and 60 minutes to complete.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Birkbeck, University of London.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Version 25. The main hypothesis concerning the effect of diet on memory was assessed using ANCOVA with dietary group as the independent variable and the memory score as the dependent variable with sleep quality as the covariate.

Result

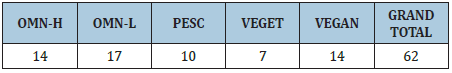

All participants were adults aged between 40 and 77 years of age. All were fluent English speakers, with English as their first or second language. There were 62 participants, 33 male and 29 females. Using the diet questionnaire, each participant was placed in one of the five dietary categories as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Number of participants by diet group.

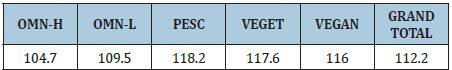

Table 2 shows the mean memory score for each diet group and the overall mean. Figure 1 shows the differences between the individual group scores and the overall mean. The statistical analysis confirmed that there was a marginally significant effect of diet on short delay if and only there was no other independent or confounding variables taken into the statistical analyses. When an ANCOVA test was run with Gender added as the covariate, the significance of the diet was lost.

Table 2: Memory scores by diet group.

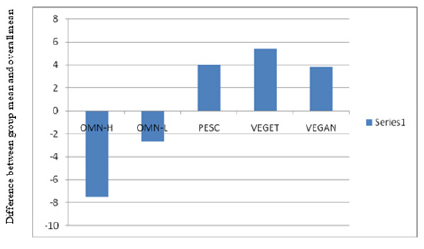

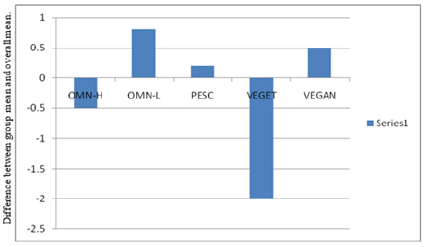

Figure 1: The effect of diet group on the difference between individual diet group mean and overall mean for verbal memory.

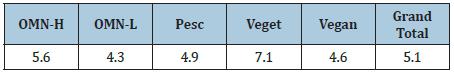

Table 3 shows the mean scores for sleep quality for the individual diet groups together with the overall mean. Higher scores signify lower sleep quality. Figure 2 shows the differences between the individual group mean scores and the overall mean score-with positive differences indicating better sleep quality. The statistical analysis confirmed that there was no significant effect of diet on sleep quality. The vegetarian group with the anomalous low sleep quality score was the smallest of the diet groups with 7 members.

Table 3: Mean scores for sleep quality.

Figure 2: The effect of diet group on the difference between diet group mean and overall mean for sleep quality.

Discussion

The rates of cognitive disorders that impact the memory are increasing globally, and it is also increasingly recognized that diet-related pathological processes such as atherosclerosis and inflammation impact cerebrovascular health leading to cognitive deficiencies. There is limited evidence that feeding on a plantbased diet (which is high in dietary fiber and vitamins) can lead to functional protection or even improvement in human cognition. In this cross-sectional observational pilot study, the association between diet and verbal learning memory was evaluated. Consistent with most earlier findings, it was found that there was a significant effect on short-delay memory, with plant-based diets showing improved performance relative to the animal-based diets when diet was the only independent variable and no confounding variable is taken into account utilizing ANOVA (Analyses of Variance). How-ever, when confounding variables (i.e. gender, sleep quality and education level) were added to the statistical analyses using ANCOVA (Analyses of Covariance), the significance of the effect was lost. A one-way ANOVA have shown no significant effect of diet on sleep quality. A chi-squared test showed that females in the sample showed significantly better verbal learning memory performances than the males in overall verbal learning memory, which is shortdelay, long delay and recognition. The results of this pilot study strongly suggest that a similar study with a much larger sample size would make a major contribution to resolving the scientific uncertainties regarding the effects of vegan diet on memory and other cognitive functions.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current diet and memory research are not publicly available due to provisions of the written informed consent.

Acknowledgment

I thank all participants for their cooperation during the CVLTstudy. I’d like to than Dr. Eddy Davelaar (Psychological Sciences, Birkbeck College, London, UK) I also thank Arthur Thornbury for his editorial assistance, who contributed to the success of my study with great commitment. I thank Prof. Dr. Mehmet Asim Karaomerlioglu (Atatürk Institute, Bogazici University, Istanbul, Turkey) and Prof. Dr. Mehmet Zafer Berkman (Faculty of Medicine, Acibadem University, Istanbul, Turkey) for providing mentorship through my studies and my research. Both received no compensation for their contributions. Further, I thank the Birkbeck College, Psychological Sciences Department for providing the laboratory, and compensatory payments to the participants, contributing to the collection of high-quality data.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Department of Psychological Sciences, Birkbeck College.

References

- Wang Y, Beydoun MA (2009) Meat consumption is associated with obesity and central obesity among US adults. Int J Obes 33(6): 621-628.

- Vang A, Singh PN, Lee JW, Haddad EH, Brinegar CH (2008) Meats, processed meats, obesity, weight gain and occurrence of diabetes among adults: Findings from adventist health studies. Ann Nutr Metab 52(2): 96-104.

- Key TJ, Fraser GE, Thorogood M, Reeves G, Burr ML, et al. (1998) Mortality in vegetarians and non-vegetarians: A collaborative analysis of 8300 deaths among 76,000 men and women in five prospective studies. Public Health Nutr 1(1): 33-41.

- Takahashi Y, Sasaki S, Okubo S, Hayashi M, Tsugane S (2006) Blood pressure change in a free-living population-based dietary modification study in Japan. J Hypertens 24(3): 451-458.

- Dinu M, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A, Sofi F (2017) Vegetarian, vegan diets and multiple health outcomes: A systematic review with meta-analysis of observational studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 57(17): 3640-3649.

- Onge MP, Mikic A, Pietrolungo CE (2016) The effects of diet on sleep quality. Adv Nutr 7(5): 938-949.

- Ferrie J, Shipley M, Akbaraly T, Marmot M, Kivimaki M, et al. (2011) Change in sleep duration and cognitive function: Findings from the whitehall II study. Sleep 34(5): 565-573.

- Null G, Pennesi L, Feldman L (2016) Nutrition and lifestyle interventions on mood and neurological disorders. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med 22(1): 68-74.

- Wade AT, Davis C, Dyer KA, Hodgson JM, Woodman RJ, et al. (2017) A mediterranean diet to improve cardiovascular and cognitive health: Protocol for a randomised controlled intervention study. Nutrients 9(2): 145.

- Sebekova K, Kudlácková MK, Schinzel R, Faist V, Klvanová J, et al. (2001) Plasma levels of advanced glycation end products in healthy, long-term vegetarians and subjects on a western mixed diet. Eur J Nutr 40(6): 275-281.

- Moraes ACF, Pititto BA, Fernandes RG, Gomes PE, Pereira AC, et al. (2017) Worse inflammatory profile in omnivores than in vegetarians’ associates with the gut microbiota composition. Diabetol Metab Syndr 9: 62.

© 2020 Pinar Sengul. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)