- Submissions

Full Text

Novel Techniques in Nutrition and Food Science

Management of Idiopathic Nephrotic Syndrome: Co-Administration of Cyclosporine and Lyophilized Grapefruit Juice

Farid A Badria1*, Ahmed F Hamdy2, Amr El-husseini2, Khaled Mahmoud2, Rashad Hassan2, Ahmed Akl2, Tarek Medhat2, Ayman Maher2, Hussein Sheashaa2, Osama Gheith2, Amgad Elbaz2, Ashraf Fouda2 and Mohamed A Sobh2

1Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Mansoura University, Egypt

2Department of Nephrology Unit, Urology and Nephrology Center, Mansoura University, Egypt

*Corresponding author: Farid A Badria, Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Pharmacy, Mansoura University, Mansoura 35516, Egypt

Submission: February 28, 2018;Published: April 19, 2018

ISSN 2640-9208 Volume1 Issue5

Abstract

Cyclosporine A (CsA) is effective in inducing or maintaining remission in patients with frequently relapsing or steroid-dependent nephrotic syndrome but unfortunately this remission is not long-lasting and most patients relapse within the few months following cessation of treatment. Use of drugs that slow CsA metabolism as ketoconazole was found to be successful in maintaining stable renal function. Certain limitations to the use of ketoconazole such as chronic liver disease, pregnancy and hypersensitivity have favored the potential use of a natural alternative. Grapefruit juice is an inhibitor of the intestinal cytochrome P-450 system, which is responsible for the first-phase metabolism of CsA. Standardized doses of grapefruit as lyophilized capsules (500mg/capsule) were administered concomitantly with CsA to study the changes in CsA pharmacokinetics. The percent rise of CsA exposure as measured by AUC was in the range of 10-25% and co-administration was found to be safe. To find which component is responsible for the observed in vivo interaction, five grapefruit juice components: Quercetin, Naringin, Naringenin, 6, 7-Dihydroxybergamottin (DHB) and Bergamottin (BEG) were screened as potential inhibitors of the metabolism of Saquinavir by human liver microsomes. Both DHB and BEG were found to be potent in vitro inhibitors of the CYP3A4-mediated metabolism of Saquinavir.

Abbreviations: DHB: Di Hydroxy Bergamot tin; BEG: Bergamot tin; CsA: Cyclosporine A; INS: Idiopathic Nephrotic Syndrome; GF: Grape Fruit

Introduction

Cyclosporine A (CsA) is effective in inducing or maintaining remission in patients with frequently relapsing or steroiddependent nephrotic syndrome [1,2]. CsA-induced remission is not long-lasting and most patients relapse within the few months following cessation of treatment [3]. Thus, CsA may have to be administered for long periods of time, exposing patients to its potential nephrotoxicity in addition to its high cost. Use of drugs particularly ketoconazole, that slow CsA metabolism among nephrotic syndrome patients was found to be successful, not only in reducing the treatment costs but also resulting in more stable renal function[4]. However, long term safety of ketoconazole administration in such patients is questioned and the use of natural fruit extract may be preferred for such indication. Grapefruit (Citrus paradise) (GF) juice, a beverage consumed in large quantities by the general population, is an inhibitor of the intestinal cytochrome P-450 3A4 system, which is responsible for the first-phase metabolism of many medications; most notable is its effects on CsA [5]. Grapefruit juice contains various components; is Naringin is the predominant compound (10% of its dry weight) and is likely to be one of the components in grapefruit that affects drug metabolism and proved to have antioxidant and hepato-protective activities [6]. However, no available evidences to confirm which compound in GF may modulate the activity of CsA. Therefore a lyophilized grapefruit juice was utilized in this study. Our aim is to study the efficacy and safety of co-administration of standard lyophilized GF capsules in combination with CsA in the management of Idiopathic Nephrotic Syndrome (INS) patients.

Patients

Patients

Twelve patients who were diagnosed as idiopathic nephrotic syndrome and being followed up in the outpatient clinic of the urology and nephrology center, Mansoura University were the subject of this study.

Inclusion criteria

a) Different age groups are included.

b) All patients are in remission both clinically and by laboratory investigations.

c) Absent relapse in the previous 6 months before inclusion.

d) All patients are maintained on stable dose of Cyclosporine A (CsA) for the previous 2 months.

e) All patients are either steroid free or maintained on not more than 10mg/day of oral prednisone.

f) Normal liver function.

g) Consent for inclusion onto the study and approval of local ethical committee.

Preparation of lyophilized grape fruit capsules (LGF)

A pre-concentrated juice was freeze-dried in a Labconco Free Zone R Freeze Dry System-model 740020 - under 46mbar and - 47 °C. The formulation used was 50% of grape juice concentrated by RO (28.5 °Brix) and 50% of hydrocolloids (37.5% of malt dextrin and 12.5% of Arabic gum). The solution of the hydrocolloids and the concentrated grape juice were mixed during 60 min and stored in an isolated container. This sample was then rapidly iced with liquid nitrogen and immediately submitted to the freeze-drying process in Pharmacognosy Department, Faculty of Pharmacy, Mansoura University, Mansoura 35516. The hard gelatin capsules, each contains 500mgs of LGF were prepared in Pharco Pharmaceutical Company, Alexandria, Egypt.

Methods

The design included three phases separated by two washout periods, as follows:

Phase one

Lyophilized grape fruit capsules were administered in a dose of 1gm/day concomitantly with CsA in the morning and evening doses (i.e. one capsule=500mg/12 hours) and maintained for 7 days. First washout period: Grape fruit capsules were withhold for 10-days period.

Phase two

Escalating dose of grape fruit was given in the same manner; 2gm/day (2 capsules/12 hours) for another 7 days. Second washout period: Grape fruit capsules were withhold for another 10 days period.

Phase three

Grape fruit was given in a dose of 3gm/day (3 capsules/12 hours) for an extra 7 days’ period.

Investigation

Cyclosporine a level monitoring

Six-Hour area under the whole blood concentration time curve (AUC):

a) CsA levels are estimated at different time points as follows: trough (just before CsA administration), 1 hour, 2 hours, 3 hours and 6 hours post CsA administration.

b) This 6-hour AUC is performed twice, both basally (before grape fruit administration) and at the end of phase 1.

Trough and two-hour post CsA administration:

a) Performed at the end of both phase 2 and 3 and also at the end of first and second washout periods.

b) Monoclonal-specific CsA kits, TDx method; Abbott Diagnostic, Abbott Park, IL were utilized.

Other laboratory investigation

Serum creatinine, albumin, cholesterol, liver function tests, complete blood picture as well as 24-hour urinary protein collection were performed at the start and the end of the 3 phases of grape fruit co-administration.

Follow up: All patients are subjected to a thorough clinical evaluation at each visit with special emphasis on administered drugs side effects.

Statistical analysis

Student’s t-test was used to compare between the two groups in continuous data, P value ≤0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

Table 1: Demographic criteria.

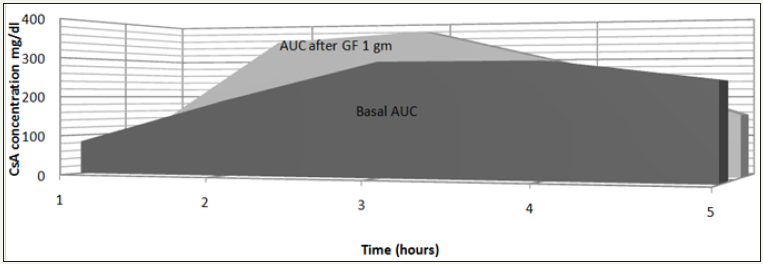

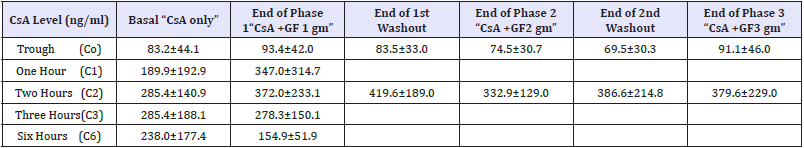

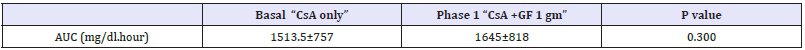

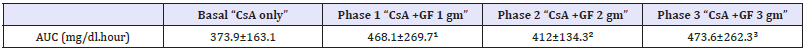

Twelve patients who were originally diagnosed as INS were enrolled in the study. The demographic criteria are demonstrated in Table 1. The patients were selected from different age groups and both sexes. All enrolled patients were clinically stable and maintained on the least effective dose of steroids and CsA that could maintain remission. Table 2a-2c shows CsA blood concentrations both basally and after GF administration at different doses. Six-hour AUC shows increased CsA concentration after GF administration at a dose of 1gm/day (Table 2b); (Figure 1) however it did not rank to statistical significance.

Figure 1: Six-Hour AUC of Cyclosporine before and after grape fruit administration (1gm/day).

Table 2a: Cyclosporine blood levels.

Table 2b: Six-Hour Area under the curve (AUC).

Table 2c: Two-Hour Area under the curve (AUC).

Note: ¹ - P value compared to AUC “basal”=0.168

² - P value compared to AUC “basal” =0.574

³ - P value compared to AUC “basal”=0.237

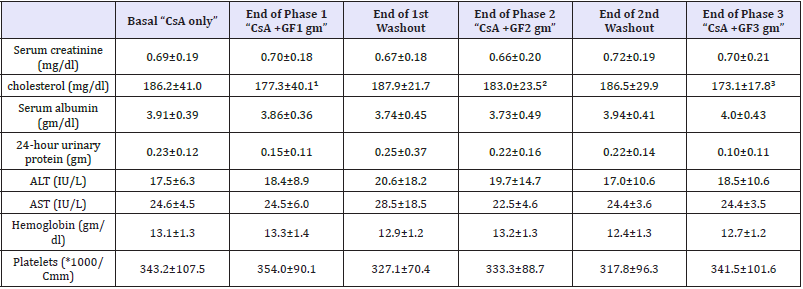

Estimation of 2-hour AUC revealed increased CsA blood concentration with GF administration at the 3 escalating doses (1, 2 and 3gm/day); however no statistical significance was encountered (Table 2c). The percentage increase of the 2-hour AUC with GF administration was 25.1%, 10.1% and 26.6% with 1, 2 and 3 gm/ day respectively. Table 3, shows stable serum creatinine, albumin, 24-hour urine protein, liver enzymes, hemoglobin and platelets at all study periods with and without GF administration. Interestingly, serum cholesterol showed mild reductions with GF administration however it did not rank to statistical significance.

Table 3: Laboratory investigations.

Note: ¹ - P value compared to serum cholesterol “basal”=0.525

² - P value compared to serum cholesterol “basal” =0.098

³ - P value compared to serum cholesterol “basal”=0. 248

Discussion

We have previously reported on long-term safety and costsaving effectiveness of ketoconazole co-administration with CsA among kidney transplant recipients [6]. Similarly, another group of our center reported on successful ketoconazole, CsA coadministration among nephrotic syndrome patients [4]. However, certain limitations to ketoconazole administration such as chronic liver disease, pregnancy, hypersensitivity have favored the potential use of a natural alternative aiming at safe and effective CsA dose reduction. The inhibitory effects of readily available commercial fruit juices on midazolam 1-hydroxylase activity, a marker of cytochrome P450, 3A4 subset (CYP3A), were evaluated in pooled human liver microsomes. The inhibitory potential of human CYP3A was in the order of: grapefruit > black mulberry > wild grape > pomegranate > black raspberry. Brunner et al. [7] have studied the benefits of co-administration of grapefruit juice with CsA in stable renal transplant patients. They found that this interaction was limited and variable and recommended not to use grapefruit juice to increase CsA levels [8]. Other editorials and commentaries have agreed, describing the CsA-grapefruit juice interaction as unpredictable and hazardous [9]. The flavonoids (Naringin and Naringenin), the furanocoumarin and Bergapten (5-methoxypsoralen), were detected in some fresh grapefruit and commercial grapefruit juices. The contents of these three grapefruit constituents in commercial juice and fresh grapefruit varied from brand to brand and also from lot to lot. Difference in the concentration of these three constituents, which have potential for drug interaction, which may contribute to the variability in pharmacokinetics of CYP3A4 drugs and some contradictory results of drug interaction studies with grapefruit juice [10].

In this study, we opted to standardize the administered dose of grapefruit by manufacturing lyophilized capsules (500mg/capsule) to be given concomitantly with CsA aiming at studying the changes in CsA pharmacokinetics among our stable INS patients. We found that co-administration of CsA with grapefruit capsules resulted in increased CsA exposure although statistically insignificant. The percent rise of CsA exposure as measured by abbreviated AUC was in the range of 10-25%. However, we failed to demonstrate progressive rise of CsA AUC with escalating doses of grapefruit. CsA, grapefruit co-administration was found to be safe as evidenced by clinical and laboratory work up. Yet, long term follow up is warranted. From the literature it is still unclear which component is responsible for the observed grapefruit juice interaction in vivo, and whether it is one component alone which is responsible rather than a combination of the inhibitory effects of multiple components. Five grapefruit juice components: Quercetin, Naringin, Naringenin, 6, 7-Dihydroxybergamottin (DHB) and Bergamottin (BEG) were screened as potential inhibitors of the metabolism of Saquinavir by human liver microsomes [11]. Both DHB and BEG were found to be potent in vitro inhibitors of the CYP3A4-mediated metabolism of Saquinavir. The data on inhibition by flavonoids is equivocal with 100mm substrate Naringenin reported to cause marked inhibition [12] or no inhibition [13,14] of Nifedipine metabolism.

Further in vivo selective studies of the all active constituents of the grapefruit juice in combination with CsA are warranted to validate the pharmacokinetic interaction.

References

- El-Husseini A, El-Basuony F, Mahmoud I, Sheashaa H, Sabry A, et al. (2005) Long-term effects of cyclosporine in children with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome: a single-centre experience. Nephrol Dial Transplant 20(11): 2433-2438.

- Niaudet P, Martin B, Ellis DA, William E (1999) Steroidresistant idiopathic nephrotic syndrome: Pediatric Nephrology (4th edn), Lippin Cott Willams & Wilkins, A Wolters Kluwer Publishers Company, Netherlands, 46: 749-759.

- Niaudet P (1992) Comparison of cyclosporine and chlorambucil in the treatment of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. The French Society of Pediatric Nephrology. Pediatr Nephrol 6(1): 1-3.

- El-Husseini A, El-Basuony F, Donia A, Mahmoud I, Hassan N, et al. (2004) Concomitant administration of cyclosporine and ketoconazole in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Nephrol Dial Transplant 19: 2266-2271.

- Badria, Farid A, El-Gayar, Amal M, El-Kashef, et al. (1994) A potent hepatoprotective agent from grape fruit Alexandria. J Pharma Sci 8(3): 165-169.

- Emilia G, Longo G, Bertesi M, Gandini G, Ferrara L, et al. (1998) Clinical interaction between grapefruit juice and cyclosporine: is there any interest for the hematologists? Blood 91(1): 362-363.

- El-Agroudy AE, Sobh MA, Hamdy AF, Ghoneim MA (2004) A prospective, randomized study of co-administration of ketoconazole and cyclosporine A in kidney transplant recipients: ten year follow up. Transplantation 77(9): 1371-1376.

- Kim H, Yoon Y, Shon J, Cha I, Shin J, et al. (2006) Inhibitory effects of fruit juices on CYP3A activity. Drug metabolism and disposition. Drug Metab Dispos 34(4): 521-523.

- Brunner LJ, Munar MY, Vallian J (1998) Interaction between cyclosporine and grapefruit juice requires long-term ingestion in stable renal transplant recipients. Pharmacotherapy 18(1): 23-29.

- Majeed A, Kareem A (1996) Effect of grapefruit juice on cyclosporine pharmacokinetics. Pediatr Nephrol 10: 395-396.

- Ho PC, Saville DJ, Coville PF, Wanwimolruk (2000) Content of CYP3A4 inhibitors, naringin, naringenin and bergapten in grapefruit and grapefruit juice products. Pharm Acta Helv 74(4): 379-385.

- Eagling VA, Profit L, Back DJ (1999) Inhibition of the CYP3A4-mediated metabolism and P-glycoprotein-mediated transport of the HIV-1 protease inhibitor saquinavir by grapefruit juice components. Br J Clin Pharmacol 48(4): 543-552.

- Guengerich FP, Kim DH (1990) In vitro inhibition of dihydropyridine oxidation and aflatoxin B activation in human liver microsomes by naringenin and other flavinoids. Carcinogenesis 11(12): 2275-2279.

- Miniscalco A, Lundahl J, Regardh CG (1992) Inhibition of 45 dihydropyridine metabolism in rat and human liver microsomes by flavonoids found in grapefruit juice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 261(3): 1195- 1199.

© 2018 Farid A Badria. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)