- Submissions

Full Text

Novel Research in Sciences

Pyoderma Gangrenosum and Pregnancy An Example of Abnormal Inflammation The Importance of Working in a Multidisciplinary Team

Hasan JA1,2,3,4, Kawsar Diab5,6, Zaynab Kalach5,6, Marwan Saliba7 and Kariman Ghazal3,4,5,8*

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Al Zahraa Hospital University Medical Centre, Beirut, Lebanon

2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Lebanese University, Beirut, Lebanon

3Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Lebanese University, Beirut, Lebanon

4Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Rafik Hariri Hospital University Medical Center, Beirut, Lebanon

5Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Al Zahraa Hospital University Medical Centre, Beirut, Lebanon

6Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Lebanese University, Beirut, Lebanon

7Department of Surgical Pathology and Cytology, Al Zahraa Hospital University Medical Centre, Beirut, Lebanon

8Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Makassed Hospital University Medical Center, Beirut, Lebanon

*Corresponding author:Kariman Ghazal, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Lebanese University, Lebanono

Submission: February 12, 2023;Published: February 24, 2023

.jpg)

Volume14 Issue1February , 2023

Abstract

A neutrophil-predominant inflammatory condition known as Pyoderma Gangrenosum (PG) manifests initially as a sterile pustule and may proceed to ulcerations. Although the underlying cause is unknown, systemic inflammatory diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, arthritis, and hematological abnormalities are frequently linked to its manifestation. Contrarily, pregnant women experience progressive neutrophilia over the pregnancy, leadoff of the pregnancy, which leads to a significant inflammatory event that aids in the onset of labor. Even though it doesn’t happen often, PG has been linked to pregnancy, which adds another link to systemic inflammation as an underlying cause of PG. We examined known case of PG in pregnant women and made assumptions about its causation based on their clinical manifestations. We also include the reported treatments and how well they like team worked for these patients.

Introduction

In 1930, Brunsting et al. [1] published the first description of Pyoderma Gangrenosum (PG). It is a rare chronic ulcerative illness whose cause is unknown. It is clinically distinguished by small beginning pustules that progress into characteristic ulcers with undermined edges and a violaceous tint. The majority of the time, PG is linked to hematological conditions like paraproteinemia and leukemias as well as systemic diseases like inflammatory bowel disorders, inflammatory polyarthritis, and inflammatory bowel diseases. [2,3]. The biopsy material lacks pathognomonic information, making the diagnosis more challenging and relying more on excluding other comparable illnesses exclusion of other illnesses that are comparable [4]. We describe a case of PG in pregnancy due to the association’s rarity as well as several peculiar presenting symptoms that made the diagnosis challenging. The value of participatingin multidisciplinary teams.

Case Presentation

When she was 31+5 weeks pregnant, a 29-year-old G3P1A1L1 woman who had previously undergone treatment for Hodgkin lymphoma during her previous pregnancy two years prior; presented with diffuse, painful, ulcerative skin lesions, erythematous pustules and papules over the legs and forearms, and an erythematous plaque rash on the cheeks . No history of weight loss and no related systemic symptoms. She has a history of cesarean deliveries and is not known to have any allergies to foods or medications. Other than multivitamins, she is not taking any drugs (iron and calcium). The patient reported that after being injured in the yard, she experienced first-trimester diffuse tender papules and a plaque rash on her arms, which quickly resolved on its own after two to three days. One month prior to admission, the lesions that started as vesicles and progressed to blisters, bullae, and pustules failed to go away despite treatment with antihistamines and topical corticosteroids. Instead, they became more painful ulcers and sores that were accompanied by itching, edema, and discharged purulentlike material (Figure 1 & Figure 2).

Figure 1: Erythematous plaques on the cheeks.

Figure 2: Bullua and ulcerations on the right and left legs.

On the cheeks, a butterfly-shaped erythematous plaque develops. On the right and left forearms, as well as the wrist, several urticarial lesions were discovered. She was restless upon admission, but her vital signs were normal. On physical examination, the uterus is in line with gestational age (31cm), and auscultation reveals clear airways. Other than the necrotizing bullous lesions on the bilateral legs, there were no other noteworthy physical examination findings. My back and abdomen were unharmed. No contractions; NST was cat1 reactive. The differential diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematous in pregnancy, unknown severe condition of vasculitis, pemphigoid gestations or polymorphic eruption of pregnancy was made during a multidisciplinary consultation that included teams from hematological, vascular, dermatology, and rheumatology. Complete blood count, CRP, electrolytes, kidney and liver function tests, and urine analysis were all part of a full laboratory workup that revealed no signs of systemic infection or inflammation. The test for hepatitis B was likewise negative. Rheumatoid factor, antiphospholipid antibodies, anti-Ro/La, and ANA autoimmune testing came out negative. Sputum, feces, urine culture, and blood did not contribute. Other than regular obstetrical morphoultrasound to evaluate the fetoplacental status and lower extremity Doppler ultrasonography, which revealed no venous and arterial thrombosis, no radiological investigations were carried out.

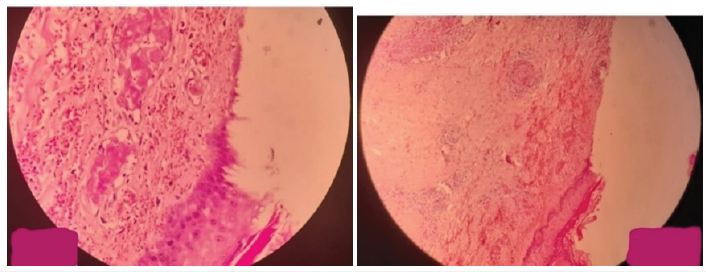

A 4x3x2cm skin and underlying tissue biopsy revealed the presence of a large central ulcer that reached deep dermis, had neutrophil infiltration, was connected to many congested and thrombosed dermal blood vessels, and had subsequent tissue degeneration and necrosis. Pyoderma gangrenosum has been identified based on histological features. The pathological specimen showed no signs of granuloma, vasculitis, or cancer (Figure 3). Benign muscular fibers in the skeleton. High doses of intravenous corticosteroids (methylprednisolone), preventive anticoagulants (enoxaparin), and calcium dobesilate were started as soon as the patient was admitted to the hospital. Prednisolone was advised as a maintenance corticosteroid therapy. After N methylprednisolone was administered for one week with dosage tapering. Within the first 48 hours, the lesions began to regress along with the pain and congestion. Bullae expelled and developed crusts. Topical ointments for daily skin maintenance were advised. After the lesions had fully healed after one month, the patient was discharged (Figure 4). She gave birth to a girl at term and is currently undergoing standard follow-up.

Figure 3: Histological studies showed neutrophil infiltration in the dermis layer of the skin.

Figure 24: Regression of erythematous plaques and ulcerative lesions on the forams and legs.

Discussion

The neutrophilic dermatoses include PG. It frequently starts off looking like pustules, erythema, and blisters before rapidly spreading in the shape of a well-defined ulcer in a centrifugal pattern. The border of the ulcer has a raised appearance, and erythema and edema are present nearby [5]. PG mainly affects the extremities [6] and can develop spontaneously, following a surgical procedure, minor trauma, or both. Between the ages of 20 and 50, PG is the most common and has a prevalence of 3 to 10 individuals per million people [7]. Men are less likely to be impacted than women [7]. Pregnancy is rarely linked to pyoderma gangrenosum. Although the exact mechanism underlying the link between PG and pregnancy is still understood, changes to the immune system during pregnancy may be a common factor. However, immune system anomalies during pregnancy may impact the immunological response, potentially leading to PG [8]. There have been several case reports of PG during pregnancy, but many of these individuals only experienced lower leg or chest symptoms [5,9-11].

Multiple instances of PG at the site of a cesarean incision [4,12- 14], and at the site of an episiotomy during the puerperal phase [13] have also been made. Therefore, it is preferable for pregnant individuals to receive early diagnosis and treatment. Due to rising levels of proinflammatory substances such as Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor (G-CSF), Granulocyte-Macrophage- Colony-Stimulating Factor (GM-CSF) and T helper (Th)-17, which may explain neutrophil hyper-reactivity, pregnant women exhibit progressive neutrophilia during pregnancy [5]. The method for treating PG in pregnant patients is the same as for treating PG in nonpregnant people. However, there isn’t a widely accepted treatment for PG at the moment [14]. Immunosuppressive medications, such as cyclosporine A or high-dose corticosteroids, are used as a form of treatment. Controlling the course of the condition during birth and the postpartum period is necessary for pregnant women with PG [11].

Avoiding traumatic lesions is the best strategy to prevent PG, according to Park et al. [15]. A vaginal birth might be preferred to a cesarean section in this regard. To the best of our knowledge, our patient’s neutrophilic dermatosis of the hand during pregnancy was the only case ever recorded to have completely resolved after treatment and before birth. Although some cases of neutrophilic dermatosis developing during pregnancy and going into remission after birth have already been reported. There are no established rules, and managerial consensus is nonexistent. The basic description of PG, a rare inflammatory neutrophilic dermatosis that prefers the lower legs, is a painful ulcer with violaceous margins. The diagnosis of PG is difficult and necessitates ruling out other non-healing ulcer causes, especially infections and neoplasms. PG is frequently linked to systemic diseases such as inflammatory bowel illness, hematologic cancers, and rheumatic diseases [9]. It’s uncertain how PG develops. Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)-a, a potent proinflammatory cytokine, is believed to be produced abnormally as part of an immune-mediated process that also includes neutrophil malfunction and aberrant inflammatory cytokines [4,5]. Corticosteroids, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclophosphamide, infliximab, methotrexate, and intravenous immunoglobulin have all been used as systemic treatments. 3,6 PG is not very common when pregnant [7,14].

The physiologic changes of pregnancy, which include increases in granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor [16], a known attractant of neutrophilic inflammation, and increased band neutrophils, may lead to conditions that resemble other inflammatory disorders, increasing the risk of neutrophildriven PG in response to local trauma. However, the majority of the women received systemic corticosteroids, and half of the patients underwent adjuvant therapy with cyclosporine, dapsone, intravenous immunoglobulin, or other medications. The patients’ treatment regimens varied. Notably, they discovered no reports of TNF-a inhibitors being applied to PG in a patient who was pregnant. Because of potential drug side effects on the fetus, treating PG during pregnancy might be difficult. Corticosteroids and cyclosporine were found to be the systemic treatments for PG in pregnancy that were most frequently used in a recent review [7]; however, steroid use can have an adverse effect on the health of the fetus, and cyclosporine can result in hypertension and renal toxicity, side effects that were worrisome given our patient’s history of preeclampsia [8].

Another generally safe therapy that has shown efficacy with PG in pregnancy is intravenous immunoglobulin. Infliximab was decided upon in consultation with her gastroenterologist as the preferable steroid-sparing medication in order to prevent risks linked to the continuing use of high-dose systemic steroids and given her history of ulcerative colitis [17]. When steroids and steroid-sparing medications are started simultaneously, it can be difficult to tell how each medication will affect the body. Systemic steroids were crucial in this situation, especially at the beginning, in reducing inflammation. TNF-a inhibitors have been successfully used to treat PG in non-pregnant individuals and, unlike many systemic therapies, are classified for pregnancy as category B by the US Food and Drug Administration [4]. However, there isn’t currently a gold standard for treatment or therapy. This is once more a result of the lack of consistency in outcome evaluation, which makes comparisons between treatments challenging [18].

Less than 20 instances of pyoderma gangrenosum in pregnancy (including pregnancy and the postpartum phase) have been documented in international literature. Despite this, there may be a connection between this disease and pregnancy. The pathergy phenomenon or the rise in G-CSF levels during pregnancy may be responsible for the connection [19]. The current patient’s concomitant morbidities were thoroughly explored. We came to the conclusion that pregnancy was the cause of this case because the latter was absent. Additionally, the location of the ulcers on the acquired striae distensae on the legs suggested that they were caused by pathology brought on by the regional stretching forces. This is an additional special characteristic in our situation that, to the authors’ knowledge, has never been documented before. We had to control the problem with only intralesional steroid injections and topical steroid treatment because most systemic medicines are best avoided. Predisposed women may experience circumstances similar to inflammatory illnesses during pregnancy, which could increase their risk of developing autoinflammatory diseases. Even if such fast consultation with a dermatologist is advised for consideration of the likelihood of PG during pregnancy, a multidisciplinary approach to the many disorders allowed for a favorable course of the pregnancy itself cases are unusual.

References

- Brunsting LA, Goeckermann WH, O'Leary PA (1930) Pyoderma (echthyma) gangrenosum clinical and experimental observations in five cases occurring in adults. Arch Dermatol 22: 655-80.

- Powell FC, Su WP, Perry HO (1996) Pyoderma gangrenosum: Classification and management. J Am Acad Dermatol 34(3): 395-409.

- Prystowsky JH, Kahn SN, Lazarus GS (1989) Present status of pyoderma gangrenosum: Review of 21 cases. Arch Dermatol 125(1): 57-64.

- Callen JP (2000) Pyoderma gangrenosum: A comparison of typical and atypical forms with an emphasis on time to remission: Case review of 86 patients from 2 institutions. Medicine 79(1): 37-46.

- Steele RB, Nugent WH, Braswell SF, Frisch S, Ferrell J, et al. (2016) Pyoderma gangrenosum and pregnancy: An example of abnormal inflammation and challenging treatment. British Journal of Dermatology 174(1): 77-87.

- Ahronowitz I, Harp J, Shinkai K (2012) Etiology and management of pyoderma gangrenosum: A comprehensive review. Am J Clin Dermatol 13(3): 191-211.

- Weizman AV, Huang B, Targan S, Dubinsky M, Fleshner P, et al. (2014) Pyoderma gangrenosum among patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A descriptive cohort study. J Cutan Med Surg 18(5): 361.

- Reichrath J, Bens G, Bonowitz A, Tilgen W (2005) Treatment recommendations for pyoderma gangrenosum: An evidence-based review of the literature based on more than 350 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 53(2): 273-283.

- Nonaka T, Yoshida K, Yamaguchi M, Aizawa A, Fujiwara H, et al. (2016) Case with pyoderma gangrenosum abruptly emerging around the wound of cesarean section for placental previa with placenta accrete. J Obset Gynaecol Res 42(9): 1190-1193.

- Miller L, Yentzer BA, Clark A, et al. (2010) Pyoderma gangrenosum: A review and update on new therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol 62: 646-654.

- Alani A, Sadlier M, Ramsay B, Ahmad K (2016) Pyoderma gangrenosum induced by episiotomy. BMJ Case Rep 2016: bcr2015213574.

- Wollina U, Haroske G (2011) Pyoderma gangrenosum. Curr Opin Rheumatol 23: 50-56.

- Aydın S, Aydın CA, Uğurlucan FG, Yaşa C, Dural Ö (2015) Recurrent pyoderma gangrenosum after cesarean delivery successfully treated with vacuum-assisted closure and split thickness skin graft: A case report. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 41(4): 635-639.

- Vigl K, Posch C, Richter L, Monshi B, Rappersberger K (2016) Pyoderma gangrenosum during pregnancy-treatment options revisited. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereo 30(11): 1981-1984.

- Park JY, Lee J, Park JS, Jun JK (2016) Successful vaginal birth after prior cesarean section in a patient with pyoderma gangrenosum. Obstet Gynecol Sci 59(1): 62-65.

- Marzano AV, Cugno M, Trevisan V, Fanoni D, Venegoni L, et al. (2010) Role of inflammatory cells, cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases in neutrophil mediated skin diseases. Clin Exp Immunol 162(1): 100-107.

- Takeshita N, Takashima A, Ishida A, Manrai M, Kinoshitha T, et al. (2017) Pyoderma gangrenosum in a pregnant patient: A case report and literature review. J Obstet Gyneacol Res 43(4): 775-778.

- De Menezes D, Yusuf E, Borens O (2014) Pyoderma gangrenosum after minor trauma in a pregnant woman, mistaken for necrotizing fasciitis: Report of a case and literature review. Surg Infect 15(4): 441-444.

- Ruocco E, Sangiuliano S, Gravina AG, Miranda A, Nicoletti G (2009) Pyoderma gangrenosum: An updated review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 23(9): 1008-1017.

© 2023 Kariman Ghazal. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)