- Submissions

Full Text

Novel Research in Sciences

For a Motive of Kindness…20 years in Federal Prison

Hancock GD*

Associate Research Professor of Finance in the Anheuser-Busch College of Business, University of Missouri-St. Louis, USA

*Corresponding author:Hancock GD, Associate Research Professor of Finance in the Anheuser-Busch College of Business, University of Missouri-St. Louis, USA

Submission: January 23, 2023;Published: February 01, 2023

.jpg)

Volume13 Issue3February , 2023

Introduction

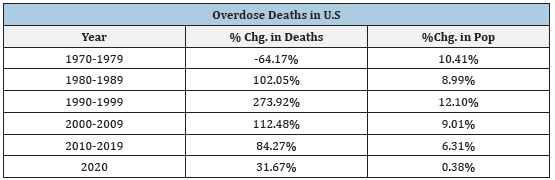

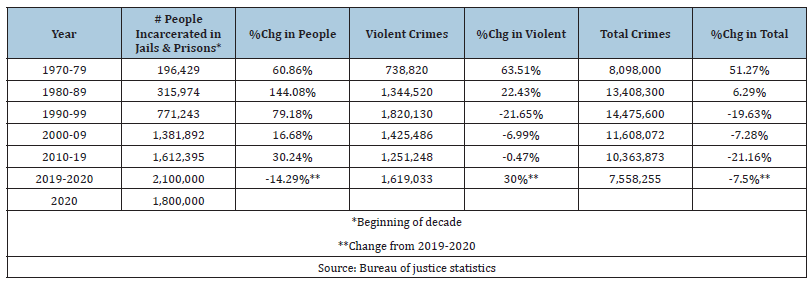

Prosecutions for Drug Induced Homicides (DIH) or Drug Delivery Resulting In Death (DDRD) have risen markedly since 2011 and are allegedly aimed at reducing opioid-related deaths, discouraging opioid use and sale, and protecting the public. Studies such as Carroll et al. [1] and Peterson et al. [2] found that a majority of prosecutions are being brought against individuals who are either low-level dealers, or are friends, family or co-users of the overdose decedent. Often these individuals are characterized in the media as profiteering “dealers” when, in reality, most people who use drugs also sell or deliver drugs to friends and relatives on occasion [3]. Yet neither state nor federal laws distinguish a user or addict from a dealer. This mischaracterization of an addict’s abilities results in many instances of the miscarriage of justice. Table 1 illustrates the failure of existing policies to reduce overdose deaths by showing the percentage change in overdose deaths in each decade beginning with the 1970’s. The 1970’s represent the only decade since the War on Drugs (WOD) began that resulted in a decline in overdose deaths. However, over the next four decades, ending in 2019, overdose deaths increased a total of 2,734.27%. Beginning in the 1980’s, overdose deaths rose 102.05% over the previous decade, and another 273.92% by 1990. The one year, from 2019 to 2020, overdose deaths increased by 31.67%. A recent November 2021 report from the Center for Disease Control (CDC) states a new record of 100,306 overdose deaths from April 2020-April 2021, driven principally by fentanyl [4]. Two of the purported goals for harsh sentences are to reduce rates of addiction and reduce drug overdose deaths. Table 1 leaves little doubt that the harsh sentencing strategy has distinctly failed at reducing overdose deaths.

Table 1:Bureau of justice statistics.

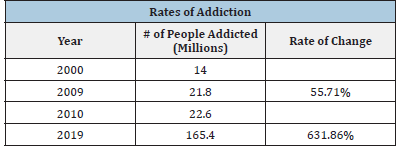

Not only have overdose deaths increased dramatically but so have rates of addiction according to the National Survey on Drug Use & Health (2000-2019). Table 2 shows that in 2000 there were 14 million current drug users, ages 12 and older in the U.S. By 2009, there were 21.8 million current drug users representing a 55.71% increase. The following decade showed a staggering increase of 631.86% in current drug users, starting with 22.6 million in 2010 and ending with 165.4 million in 2019. Clearly, harsh policies have accomplished the opposite result of discouraging opioid use and sale. No matter how one looks at the outcomes of the WOD, it has failed. Peterson et al. [2] agrees stating that “The rationale of seeking to protect people who use drugs is often given to justify harsh sentences for fentanyl distribution, yet there is no research or data set that supports this justification.” As time has passed and new research has emerged, there are reasons to believe harsh drug laws result in additional overdose deaths. Studies, such as Koester et al. [5], Wagner et al. [6], Banta-Green et al. [7], show that strict DIH laws have resulted in a decline in “911” calls for overdoses because people are afraid they will be charged. To the extent this holds, it increases the risk of overdose deaths and is in direct conflict with the Justice Department’s stated goals.

Table 2:National survey on drug use & health (2000- 2019).

Varner [8] argues that rather than offering any sort of deterrence effect, these DIH statutes are inappropriately holding drug dealers strictly liable for homicide1. Even if the accused had no intent to do harm, they still receive sentences that far exceed any that are considered permissible under a traditional public welfare analysis and appear too severe to pass constitutional muster [9]. Phillips [10] provides additional legal insight into the incompatibility of DIH statues with due process as guaranteed by the Constitution. He examines the development of strict liability offenses in the American legal system and asserts that criminal intent or men’s rea, is an indispensable due process protection in homicide law. Phillips argues that DIH laws are functionally unconstitutional and inconsistent with the spirit of due process. Buikema [11] agrees that the deployment of harsh criminal penalties for addicts as retribution for an accidental overdose death raises serious constitutional questions that have been largely ignored. For example, the motives or intentions of the addict are never considered in sentencing, thereby denying a fully vetted due process for the defendant [11,10].

The legal questions, as they relate to the felony murder doctrine, have been explored elsewhere by history scholars, epistemologists, and criminal law theorists. The resulting consensus is nearly unanimous regarding felony murder and other provisions that are corollaries to DIH: they are both flawed law and damaging criminal justice policy [12,13]. Even so, drug induced homicide laws are rapidly expanding beyond the federal government to the states. Currently, twenty-six states have implemented specific DIH laws in response to the opioid crisis. Other states bring charges of first-degree murder, second-degree murder or manslaughter in DIH cases. The surge in the utilization of harsh punishments is particularly alarming because it has produced the opposite results as desired and is at direct odds with: the findings in academic research, health sciences reports and successful recovery programs. The gap between the criminal justice approach and the science-based approach to addiction could not be wider. Narrowing this gap is a necessary step to criminal justice reform but far from the most challenging. The most fundamental aspect needed for reform is an alignment of the underlying purpose of incarceration. Is the purpose to: punish? seek revenge? promote public welfare? protect other citizens from violence? Without a foundational understanding on both sides of the purpose of incarceration, the gap between the criminal justice approach and the science-based approach will likely widen.

It is likely that the judicial system uses punishment and retribution as the central instruments to control unwanted behavior due to social and decedent family pressures, rather than objectively evaluating the facts and doing the difficult work to incorporate scientific findings into workable solutions for addicts. Socially, addicts are viewed as the lowest rung of society, ‘gutter people’ who get what they deserve. Addicts are widely viewed as those who have no willpower, but Snoek et al. [14] argue that willpower is much less important to explaining recovery than the prevailing view suggests. When society believes that the real issue is willpower, it is not surprising that so many blame the addict for his lawless failings. This causes many to see DIH laws as an essential tool for controlling the overdose crisis and harsh sentences to be justified punishment for the addict’s depraved behavior. This argument has not been accepted by the academic or scientific communities because the data does not support the conclusion that harsh DIH laws are effective in protecting public welfare. In spite of the evidence of failure and the Constitution, the justice system appears to be mindlessly devoted to a failed strategy of punishment and retribution, despite significant evidence that it has caused the situation to worsen.

This paper offers the unique insights of a federal prisoner, GS, charged with a DIH and eventually sentenced to 20 years, to highlight the issues surrounding motive, addiction, minimum sentences and prosecutorial misconduct. To aid in the sentencing discussion, a sample of 50 DIH cases was selected to compare and contrast sentencing among state and federal prosecutions.

A Motive of Kindness

GS is a 32-year-old Caucasian man, sentenced to 20 years in federal prison for a drug induced homicide that occurred in October 2018. There were 6 fact-gathering phone conversations between GS and the author between June 25, 2021 and November 15, 2021. In addition to phone conversations, there were several fact-gathering e-mails exchanged through December 13, 2021. A secondary search of three criminal records services sites revealed that GS had one previous misdemeanor permit violation and one misdemeanor assault charge. GS was born and raised in the suburbs of St. Louis, MO, attended public school and lived in an upper middle-income neighborhood with his sister and dual-career parents. There were no gangs, weapons or desperation in his life experience. At age 16 or 17, GS had painful kidney stones and was prescribed Vicodin, which became an addiction that plagued him throughout college. GS graduated from the University of Missouri in 2014, earning a bachelor’s degree in Business Administration. The mild part of GS’s opioid addiction began to disappear after college as he secretively became addicted to heroin. After landing his dream job, he lost it four weeks later due to non-performance issues. For the third time, GS entered a rehabilitation program and for the third time he relapsed. But this time, he ‘graduated’ from the rehab program with new ‘friends’ that introduced him to fentanyl. GS describes his addiction as a major obsession. He floated from job to job, unable to hold a position for any significant amount of time. At 25, his parents asked him to move out, although he had nowhere else to go. He stayed with different friends until he had exhausted his welcome due to his advanced opioid addiction, which by now had progressed to fentanyl. Within a year of moving out of his parents’ house, GS was homeless. Shelters were not as friendly to men as they were to women and children.

As with all opioid addicts, GS learned the severe pain that comes from withdrawal each time he could not obtain drugs in a timely manner. Even the withdrawals under medical watch were unbearable. He described one withdrawal episode that started with being naked, covered in sweat and vomit, curled in a ball in the corner of his room. The odor was rancid and the pain was constant for three days with no relief. After the third day, he was able to hold down a piece of bread and some water. Over a period of two to three weeks, GS suffered bouts of a hell he would not wish on his worst enemy. Many times, he wished he could just die because he did not have the strength to fight this addiction any longer. GS said, “The funny thing about withdrawal is that addicts spend 100% of their time trying to avoid it.” GS surrounded himself with other addicts and drug sharing was the norm. When one addict was short on heroin or fentanyl, another addict in the group would sell to them, with the expectation that the favor would be returned when the need arose. This type of sharing among addicts is a common way of reducing the risk of withdrawal. When the circle of friends is large, there is a lower probability of running out of sources for drugs2.

One of GS’s friends, TG, contacted him in October 2018 to ask if he had access to five beans of fentanyl. The word bean is used to describe capsules, ideally filled with a mix of fentanyl and dormant material. In practice, the beans can be filled with almost anything and present the initial risk of death for addicts. GS had no fentanyl beans but his roommate did; he bought thirty beans of fentanyl, twenty-five for himself and five for TG. GS injected himself with 3 beans of fentanyl and noticed it was stronger than expected. He told TG, in a text message, about his experience and the fact the fentanyl seemed strong. TG was scared of withdrawal and desperate for her family not to see her go through this because then they would know she had not been clean. She insisted on the fentanyl anyway and drove to GS’s house to pick up the five beans in exchange for $20, paid to his roommate. She returned home and snorted two beans of fentanyl. Her family found her deceased the next morning and the coroner ruled she died from an overdose of fentanyl. The family called the federal Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) and shared the text messages found on TG’s cell phone and a federal investigation was supposedly launched. The ‘investigation’, however, only centered on GS because TG’s family blamed him for their daughter’s death. No attempt was made to find the dealer who sold the drugs to GS, even though text messages made clear that GS had contacted someone else for the drugs. Instead, the investigation centered on trying to build a case against GS as a dealer.

GS describes the initial experience with police and the withdrawal: “The klonopin [clonazepam] I took had not yet hit me when I was arrested in front of my house on February 11, 2019. I only remember bits and pieces of the hours-long interrogation and the rejection of my request for a drug test. I was sitting on a bench in a hallway, handcuffed and passed out when I was awakened by an officer. The next thing I remember is being in a single-man holding cell in Jennings [Missouri] eating spaghetti. I have no idea how I got there…I don’t remember the ride or walk or whatever brought me to this place. I only remember the enormous, inescapable pain of early withdrawal. Shortly, I was moved to Macoupin County Jail [Illinois] where I had a huge guy for a cell mate. That only lasted one day before he asked for me to be moved because I stank so badly. The guards asked me to take off everything at booking so I didn’t even have boxers for the first week. The withdrawal, mixed with grinding fear, then started in earnest. I couldn’t eat, I stank, had horrible gas, sweat and gut-wrenching pain. I cried out as it got worse. I was shaking, trembling and could not sleep at night. I was put on some sort of withdrawal medication in the second week, which I believe caused me to begin hallucinating. I could not separate reality from my hallucinations which were frightening in their intensity. One time, I thought we [inmates] were watching a movie about a space academy where people learned to fly space crafts. I believed that other inmates who were taken from the common area were on the space ship and could drop off weed on the side of the jail.”

“I believed there were cases of Mountain Dew (my favorite) under my bed and I was under the bed drinking the soda. I thought my mom had ordered Domino’s pizza here and we were eating pizza and drinking Mountain Dew. I thought the guards let me go up front to get my big black jacket and I got real cigarettes out of the pockets and gave them to people in the common area. But then I ran out and I had to go and ask for some back. I must have looked insane talking about something I didn’t have, giving something that wasn’t real to someone who was not really there. I remember banging on the doors and telling the guards I was not supposed to be here. I thought I had one job to do for the guards before they would let me leave. Hallucinations continued to plagued me for almost a year. I thought I was working for a female FBI agent and helped bust a huge load of cocaine in hidden compartments of a car.

While we were searching, the cartel drove by and shot me 16 times. In real time, one of the guards opened my cell and I popped up as if I had a gun in my hand, old western style. I had a shoot-out with the guard, using my hands as a guns…unfortunately, many people in the common area saw this and it has only been recently that enough people have left the jail for the story to stop being told. The daily physical gut-wrenching pain was masked by total lunacy, the world was blurred, there was no clear line between truth and fantasy. I could not separate the physical pain from the world around me and I lived and I suffered. I thought how could trying to help someone avoid this be so wrong. I really believed it [selling TG five beans] was an act of kindness.” GS was sentenced to 20 years in federal prison despite having no previous felony arrests, no evidence that he was a dealer and no weapons or drugs found in his home or on his person. Federal incarceration does not allow for parole.

Mandatory Minimum Sentences

Mandatory minimum sentences are meant to apply to all individuals who have committed the same crime, regardless of the unique circumstances. Typically, these minimums most often apply to weapon and drug crimes. The goal is to ensure that all persons committing the same crime do the same time. That sounds reasonable except it does not work in practice. Of the fifty DIH cases reviewed for this study, none of the accused had the same background, same circumstance, same motive or same level of culpability. In some cases, weapons were involved, in other cases the accused administered the deadly drug to the decedent and in other cases the accused had a lengthy record of past criminal activity. It is not possible to have a one-sentence-fits-all approach because one sentence does not make sense for such diverse cases. More importantly, since the law does not distinguish between an addict or user and a dealer, the sentence is the same regardless. Most likely this is due to the waiver of the men’s rea requirement, which effectively makes the motive irrelevant. Instead, harsh sentencing is used to supposedly send a signal to others who are selling and using drugs that they will be severely punished. However, in order to send a signal to a healthy brain, the message must be clear, consistent and repetitious.

State DIH laws are anything but, because each state has its own set of rules, its own minimums and its own guidelines. In fact, one of the state cases reviewed was dismissed entirely after a plea deal with the prosecutor. Additionally, the federal government’s DIH laws are different from the states, providing zero opportunity for a clear, consistent, repetitive message. Furthermore, opioid addicts do not have a healthy brain that can receive or interpret consistent messaging because the neural circuits needed to process that information have been disrupted or destroyed [15,16]. Levy [17] argues this neural circuit damage results in addicted individuals making poor choices despite awareness of the negative consequences; it explains why previously rewarding life situations and the threat of judicial punishment cannot stop the addict from taking drugs and why a medical, rather than a criminal, approach would be more effective in curtailing drug use. Logically, it is not surprising that the threat of lengthy imprisonment does not impact the opioid addict’s behavior when the threat of death does not change their behavior. It is counterintuitive to argue that harsh sentencing will deter drug use when death does not.

When asked about the deadly consequences of fentanyl, GS explained: “Well, everyone knows fentanyl can kill you, but once you start using it and get addicted to it and you see you haven’t died after using it multiple times and it’s done nothing but make you feel good, you try to just use it as carefully as you can by going off how much you used last time and how it made you feel last time you used it. The thing is, you are going to use it either way no matter what because the withdrawal is horrific and is every dope fiend’s worst fear. Naturally, you’d rather get high than go through withdrawals, so no matter what you are going to use even though you know it may kill you. It’s like after you get addicted to it, you deny that it can kill you. Like for me, I had overdosed on it a bunch of times and ended up in the hospital and never died, so I am like well it can’t kill me and if it does, who cares? My life is already fucked up–I spend all my time chasing the dragon to avoid the pain of withdrawal. What’s one more life, even if it’s mine?”

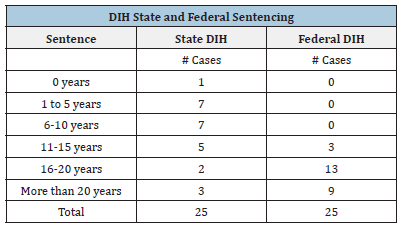

Table 3:

A follow-up question was asked about how this denial works

when co-users in the group begin to die. GS knew three people

who had died from a fentanyl overdose within an eighteen-month

period of time. His response was stunning: “Hahaha I am so sorry

to laugh at the question but it never made sense to me either and

is probably the craziest thing of all. What if the fentanyl or heroin

starts killing people you know? The first thing you do is ask where

they got it from because that’s good shit. That’s the god’s honest

truth, any heroin addict will tell you the same thing because if

it’s killing people... That’s the good shit....”. To further investigate

the threat of lengthy imprisonment for addicts, 25 state and 25

federal DIH cases were examined. The cases were obtained from

publicly available sources such as news stories, FBI releases, Justice

Department reports and DEA commentaries. Of the 25 state cases,

24 (96%) were settled in a plea agreement with the prosecutor; all

25 federal cases ended in a plea deal. Table 3 shows the frequency

of various prison sentences. Of the 25 state convictions reviewed, 3

(12%) resulted in a sentence of more than 20 years while 36% of

the federal cases did the same. The federal cases resulted in a 20-

year sentence in 13 (52%) of the cases while the state cases most

frequently (56%) result in a sentence of 1-10 years. Three fairly

clear conclusions arise:

i. It is better to be arrested by state authorities than by the

federal DEA.

ii. The distribution of sentences offers no consistent messaging

to users, addicts or dealers.

iii. If the accused has information to share, the sentence can be

reduced or possibly even eliminated through a plea deal.

Research shows that the impact of mandatory minimums for federal sentencing have not improved public safety and have exacerbated racial disparities within the justice system [18,19]. As Gilpin [20] puts it “After an eye-popping price tag of $1 trillion, most scholars consider this war on drugs to be an unmitigated failure analogous to Prohibition-era policies. While the U.S. is home to 5% of the world’s population, it holds 25% of global prisoners.” Gilpin disputes the increasing use of mandatory minimum sentencing due to its inherent flaws and inability to achieve its aims. With mandatory minimums, judicial discretion is eliminated and overly harsh sentences are common place. Moreover, mandatory minimum sentences are inconsistent with the principle of proportionality3. The common justifications for the imposition of harsh sentences have no empirical support given the rising rates of addiction and overdose. The case for the imposition of mandatory minimums is significantly weakened by the multitude of unanswered questions from academics, scientists and practitioners who have presented evidence raising serious doubts about its efficacy.

The one absolute that all parties seem to agree upon, regardless of other views, is that fentanyl is the most deadly, cheap drug to ever hit the U.S. black market in massive quantities. It only costs $5 to kill yourself.

When asked about the threat of a long prison sentence, it was clear that GS was unaware: “Regarding the laws on overdose deaths, no one in my group even knew anything like this could happen, no one knew that if you helped a friend get drugs that you could get a 20-year sentence, that’s insane, because everyone was helping each other get drugs. Like I told you before, every dope fiend I ever met, including TG, helped their friends get drugs at some point, it’s just the way it works.” It is not surprising that the judicial system has been unmoved by the failures of minimum sentences because it seeks an outcome that is motivated by the need to punish or to seek revenge, regardless of the end result. Consider, for example, prosecutors who obtain long sentences for the accused. Those prosecutors are described in reports as ‘better’ or ‘tougher’ than those who obtain short sentences. Long sentences are a valued reputational achievement for prosecutors and reinforce the need to seek higher prosecution rates and longer sentences [21,22].

A more comprehensive method for incentivizing prosecutors is needed to change the current focus from punishment to justice. Justice requires weighing both sides of the story and, when appropriate, dismissing a case or reducing the sentence. This requires a system that rewards prosecutors for such decisions. Forty states have relaxed some of their drug laws over the past 5 years, particularly marijuana laws, recognizing that a rational approach to drugs is much more cost effective and beneficial than a revenge-punishment approach. Even so, both federal and state governments continue to increase law enforcement and impose extreme sentences in DIH cases without evaluating the costs and benefits of their actions. Pitzer P [23], a retired warden, gives his thoughts on sentencing: “The 1980s “get tough on crime” and war on drugs agendas resulted in substantial changes to sentencing and correctional structures. From the abolition of parole to mandatory/ minimum sentences, these initiatives resulted in prison populations larger than anyone could have ever anticipated.

I entered the Bureau of Prisons in 1973. By 1980, the federal prison system had 24,000 prisoners; today federal prisoners total 156,428. Each year we lock up more individuals than we release. How long can this continue? How long can the American taxpayer foot the bill for increased incarceration? And more importantly, is it necessary? We have removed common sense from the federal judge’s arsenal and determined that one prescription, longer and longer terms of incarceration, fits all. We spend more money as a country incarcerating an individual than educating our kids. I am not saying that some people don’t need to go to prison. I am saying that long prison sentences without the benefit of common sense and real investment in reentry programs create a bigger problem than we had to start.” The warden makes several important points, including the forfeiture of common sense in sentencing and the cost burden to the American taxpayer. For every 100,000 people in the U.S., there are 710 incarcerated, according to an estimate obtained from the Prison Policy Initiative. The Bureau of Justice Statistics estimates the annual cost of incarceration in the U.S. at $81 billion per year to house 2.3 million prisoners.

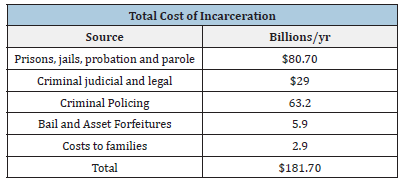

This estimate does not include policing costs, court costs or the costs paid by families to support incarcerated family members [17,24]. The Prison Policy Initiative sought to understand the total costs required to imprison millions of people [25]. The breakdown in Table 4 shows that a broader view of the costs associated with mass imprisonment in 2017 amounted to approximately $181.7 billion per year. The Cato Organization estimates that the total cost Americans have paid on the first item-prisons, jails, probation and parole-from 1971-2015, is over $1 trillion, representing a conservative estimate relative to another research. The title of Lopez G [26] article sums up the message clearly, “Mass incarceration doesn’t do much to fight crime. But it costs an absurd $182 billion per year. A new report suggests mass incarceration costs even more than we previously thought [26]. The increased rates of incarceration and expanding costs over the past three decades are puzzling given that crime rates steadily declined over that same period of time, as shown in Table 5. Interestingly, in the 2019-2020 time period, total crimes decreased by 7.5% but, for the first time since the 1980s, violent crimes increased by 30%.

Table 4:Prison policy initiative, 2017.

Table 5:Incarceration and crime rates.

The 1970’s saw an increase of 60.86% in the number of people incarcerated followed by 144.08% increase in the 1980s. The initial increase was prompted by President Richard Nixon’s WOD. President Ronald Regan continued the fight through the 1980’s by pouring $21.54 billion, or $72.37 billion in today’s dollars, into the effort. The prison population ballooned by another 79.18% in the 1990’s. The twenty-first century continued to produce increases in the prison population until 2020, when COVID-19 quarantined large populations of people around the globe. Thousands of low-risk prisoners were released and prison populations thinned to reduce the COVID-19 risk to prison staff and remaining prisoners. In the end, the total jail and prison population declined by approximately 300,000 [27]. Even so, the U.S. still has the highest incarceration rates in the world, now representing approximately 4.25% of the global population and 20% of the world’s prisoners.

Addicts, Survivors & Victims

Opioid addicts

Unfortunately, active opioid addicts cannot be good students, workers, planners, organizers or, more importantly, drug dealers. To understand the absurdity of characterizing an addict as a dealer, one must understand opioid addiction. The National Institute of Health defines addiction as “a chronic, relapsing disorder characterized by compulsive drug seeking, continued use despite harmful consequences, and long-lasting changes in the brain.” Addiction is considered both a complex brain disorder and a cognitive illness. It is estimated that addiction is the most severe form of a full spectrum of substance-use disorders, and is a medical illness caused by repeated misuse of a substance or substances [28]. “A common misperception is that addiction is a choice or a moral problem, and all you have to do is stop. But nothing could be further from the truth,” says Dr. George Koob, director of NIH’s National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. “The brain actually changes with addiction, and it takes a good deal of work to get it back to its normal state. The more drugs or alcohol you’ve taken, the more disruptive it is to the brain.” [29].

Almost 21 million Americans are believed to have at least one addiction, yet only 10% of them receive treatment due to the strong negative social stigmas attached to the label addict. Researchers have found that much of addiction’s power lies in its ability to seize and destroy crucial brain regions that are meant to help humans survive4. Repeated use of drugs can damage the essential decision-making center in the prefrontal cortex area. This is the region needed to recognize the harms of using addictive substances [30,23]. According to the National Institute of Drug Abuse [16], heroin, morphine, and fentanyl work by binding to the body’s opioid receptors, which are found in areas of the brain that control pain and emotions. Over time the brain adapts to the drug, diminishing sensitivity and making it hard to feel pleasure from anything besides the drug [31]. This starts the chain of addiction, with drug seeking and drug use taking over an addict’s life. Increased opioid tolerance also acts as a depressant, which can slow the body’s natural systems (e.g., respiratory and cardiac). Over time, this disruption leads to very serious consequences like stroke, heart failure or death [29].

Worse yet, researchers have found that continued opioid abuse deteriorates the white matter in the brain. White matter, which comprises about half the brain, affects learning and brain functions; it modulates the distribution of action potentials, acting as a relay and coordinating communication between different brain regions [32]. When white matter deteriorates, it results in shortcircuiting a person’s problem-solving ability, learning capacity and ability to remember [30,33]. In general, an addict’s ability to think diminishes and confusion grows. The cognitive, physical and psychological deterioration of an addict prohibits the possibility of being able to function as a successful dealer, or anything else. Addicts become unable to perform even the necessary daily activities to care for themselves, are unable to remember simple engagements and are unable to plan or organize. To label addicts as dealers is a clear fabrication of the reality in which they exist. Misleading labels can be dangerous as they often lead to unfounded and unfair judgements against the addict who may have wished at some point that he were a dealer but is simply not capable of meeting the demands.

Hudack J [34] summarizes the waste and the loss well: “The war on drugs, not the war in Afghanistan, is America’s longest war. It has used trillions of American taxpayer dollars, militarized American law enforcement agencies (federal, state and local), claimed an untold number of lives, railroaded people’s futures (especially among Black, Latino, and Native populations), and concentrated the effort in the country’s most diverse and poorest neighborhoods. The war on drugs has been a staggering policy failure, advancing few of the claims that presidents, members of Congress, law enforcement officials, and state and local leaders have sought to achieve. The illicit drug trade has thrived under prohibition; adults of all ages and youth have access to illicit substances. Substance use disorders have thrived, and policymakers’ efforts to protect public health were fully undermined by policy that disproportionately focused, if unsuccessfully, on public safety. It is time for an American president to think seriously about broad-based policy change to disrupt the manner in which the United States deals with drugs.”

Addict survivor

The Addict-Survivor (AS) is the person who consumed the drug but did not die. This is the person that is most frequently and erroneously identified as the ‘dealer’ in DIH charges. As noted above, addicts cannot function as dealers, even if they have a desire to do so because they are plagued with physical, cognitive and psychological problems that make it impossible. Addicts often find themselves unemployed, having been fired from multiple jobs, and fantasize about easy money: money for drugs. Being a dealer sounds easy enough to addicts and they believe (incorrectly) it does not require sobriety, so it appears to be a good fit with the fantasy of easy money. GS describes his experience: “A few years back, I thought dealing drugs was the answer to my money problems. I thought it would provide steady access to drugs and I could make some money at the same time. It did not work out that way though. Instead, I ended up owing the dealer $330, money I did not have. Some rough looking guys showed up at my house with a gun and told me to figure out how to get the money NOW, or else. They weren’t kidding around. So, no dealing didn’t work out for me but I shared it with friends. I’ve never met a heroin addict that doesn’t share or give drugs…it’s in their best interests to do so. In the law’s eye, I guess all opioid addicts are dealers.”

The first challenge of being an addict-dealer is grappling with distributing a drug that the addict is desperate to consume. Too often the addict uses the drugs to either get high or pay other addicts for past drugs used or more likely, both. With the drugs for distribution depleted, a cash problem arises for the addict who now finds himself in debt to his dealer with no way to repay the full amount. Jacques, Allen and Wright (2014) find that dealers typically “rip-off” people who are addicted to drugs because they are unlikely to realize what has happened and most are unwilling to retaliate or complain. Dealers also perceive addicts as needy and not worth the trouble they cause.

Similar to drug dealers, the justice system also victimizes addicts as it has other mentally ill groups of people throughout history [35- 38]. On one hand, mental health professionals describe addiction as a complex brain disorder and a cognitive illness, while on the other hand, prosecutors are taking bows for locking addicts in prison. To prey on those with cognitive illnesses or brain disorders is not only bullying at its ugliest, but also cruel. Casual observation of the overdose death rates makes clear that the punishment-revenge approach to drug use has been a failure for all parties involved and has cost taxpayers trillions. For the reasons discussed, an addict cannot be a dealer of any import. They are simply not equipped to handle even simple business transactions, e.g. paying bills, much less navigate a more complex and dangerous drug network.

Addict victim

AVs who die from overdoses have essentially laid the table for their death with their combined decisions to: buy a deadly drug, ingest the drug, determine the ingestion method, take too much of the drug and take the drug when other drugs are in their system. The AS is then invited to bring desert to a stage that has already been set for death. All addicts are victims of their drug use and when addicted to a drug as deadly as fentanyl, that often means death will follow sooner rather than later. In this context, the Addict-Victim (AV) is the decedent and the AS remains among the ‘walking dead5.’ Fentanyl addicts appear to be well aware that their activities are both illegal and dangerous enough that death could result. Even the threat of death is not enough to overpower their opioid addiction. It is not the actions or the behaviors of the AS that trigger the AV’s drug seeking-behavior.

In the case of GS versus USA, there was no evidence suggesting that GS prompted any communication with TG to exchange fentanyl. Instead, it is the progression of advanced opioid addiction that causes the AV to seek out the AS. In fact, TG was 25 miles from GS when the fentanyl was ingested, so it was not possible for GS to have influenced TG’s choice of snorting as the delivery method nor the choice to administer two pills instead of one or none. In addition, TG failed to have any life-saving drugs (e.g. naloxone) available to prevent overdose; this practice is becoming increasingly common among opioid addicts [39]. In one respect, opioid addicts are luckier than some other types of addicts because of the existence of an opioid antidote to prevent death in case of an overdose. Recovery groups, books and organizations seem to be very clear and consistent on how to allocate responsibility. It starts with both the AS and AV taking responsibility for their own actions but not for the actions of each other. The AS is responsible for the action of providing the drugs but is not responsible for the actions of the AV after delivery. The AV has choices after the drugs are obtained, he can: discard the drugs, sell the drugs, give the drugs to a parent or trusted sponsor, choose the amount and method of administering the drug, etc.

Furthermore, only AVs know how many and what kind of drugs are already in their system at the time they choose to take additional drugs. It is rare in DIH cases for autopsies to show the consumption of only one drug; normally there is a mix of prescription and nonprescription drugs in the blood stream. This presentation of the AV makes it extremely difficult for a toxicologist to obtain clean results as to which drug, or drug mix, was the actual cause of death [40]. Fentanyl is known to negatively interact with at least 551 different drugs; 246 of which are categorized as major interactions, 302 moderate, and 3 minor [41]. Common medications for depression, ventricular arrhythmias, antihistamines, muscle relaxants, hypertension, edema, etc6. negatively interact with fentanyl in such a way as to increase its potency or exacerbate symptoms. Legal drugs such as alcohol and cannabis7 also contribute to the toxicity of fentanyl, making it impossible for an AS to assess the toxicity and tolerance levels of the AV. However, it is relatively easy for each addict to assess such information for themselves by using on-line public information.

Prosecutorial Misconduct

Emerich’s [42] characterization of unchecked power, stated 134 years ago in his letter to the Bishop Mandell Creighton, still resonates today when applied to prosecutors: “Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Great men are almost always bad men, even when they exercise influence and not authority: still more when you superadd the tendency or the certainty of corruption by authority. There is no worse heresy than that the office sanctifies the holder of it. That is the point at which . . . the end learns to justify the means. You would hang a man of no position . . but if what one hears is true, then Elizabeth asked the gaoler to murder Mary, and William III ordered his Scots minister to extirpate a clan. Here are the greater names coupled with the greater crimes. You would spare these criminals, for some mysterious reason. I would hang them higher than Haman, for reasons of quite obvious justice; still more, still higher, for the sake of historical science. . . .”.

Not surprisingly, research shows that prosecutorial misconduct is actually associated with a decrease in the odds of identifying the true perpetrator [43]. This proved to be true in the case of GS, when no interest was ever shown in identifying the provider of the drugs. GS was criminally charged on Feb 11, 2019, with 1 felony count of drug induced homicide in the case of TG’s death. His request for a drug test upon arrest was denied but a taped interview left little doubt as to the state of GS’s mind. Guilt was already established in the minds of the DEA officers upon arrest, as evidenced by their words to GS and, separately, his family, that he would be going away for a long, long time. Despite evidence to the contrary, the prosecutor assumed GS was 100% responsible and guilty, as evidenced by the lack of interest in the person who originally sold the drugs. GS was remanded to the custody of a local jail, with no bail, until his sentencing date more than two years later. During the first year of his incarceration, GS was in a confused cognitive state due to his withdrawal from fentanyl. As a result, he was often bewildered and could not process the information he received from his attorney. Learning for the first time that he could be sentenced to 20 years seemed like another hallucination, not reality.

Six months prior to TG’s death, GS’s best friend since middle school, CP, died from a fentanyl overdose. CP had just been released from prison on a drug-related charge and contacted GS to celebrate his release. CP bought what he thought was heroin from an old dealer contact. Unfortunately, the heroin was laced with fentanyl. GS almost died and CP was found dead in a chair on the patio the next morning. There was an investigation and the seller of the laced heroin was found and arrested, according to St. Louis police. The story of CP is important because of the steps the prosecutor took next. GS was offered a plea deal: skip the jury trial in exchange for a 15-year sentence and agree to testify against the dealer who sold drugs to CP. Unsure of the consequences of testifying against a drug dealer, GS naively declined the prosecutor’s offer, not realizing this was not a free choice. Within 48 hours of declining the prosecutor’s offer, GS was indicted on two additional felony charges related to CP’s death, each carrying a mandatory minimum 20-year sentence and a second attorney was appointed to take the cases. Now GS faced a potential 60 years in prison versus 15 years if he agreed to testify and waive a jury trial.

Prosecutorial abuse in the GS case went beyond manipulating the facts, to threatening his family. The power the prosecutor held over his precarious situation belatedly sank in for GS, as did the impotency of the judge. Prior to this encounter with the law, GS believed judges held all the power and prosecutors were truthseekers. Nothing could have been further from the truth. The new attorney negotiated with the prosecutor to allow GS to plead guilty to the original charge of DIH in the death of TG in exchange for dropping the other two charges in the case of CP. Seeing no real choice in the matter, GS plead guilty to the first charge, the other charges were dropped and the prosecutor gave him the minimum sentence of 20 years. Upon reflection, GS said: “This was my family’s first exposure to the criminal justice system, we didn’t even know there was a big difference between the state and federal legal systems and ended up hiring a ‘state’ attorney for a federal case. That’s how naïve we were of the situation that I was in. I always believed that in the U.S. legal system you were innocent until proven guilty; what I found out is you are actually assumed guilty, until you can be proven guiltier. When I couldn’t cooperate and plead out to a 15-year sentence they [the prosecutor] decided to indict me on two additional random felonies in which I was, according to the police investigation, a victim. How is that even possible to be charged like that…is it even legal? Once I was indicted on the additional counts, instead of 15 years, I was looking at a minimum of 60 years and a maximum of 3 life sentences. I had never been in serious trouble before, that was absolutely insane. I can’t think of anyone who wouldn’t plead guilty with that much time being on the line. I felt I had no choice but to say I was guilty. Once I was in jail for the first charge, I started looking up statistics for the federal system and I found out that only 3% of federal drug cases end up in acquittal. In order for me to get acquitted, I would have had to go to two different trials and win both and all this over an accident?? I naively believed that the job of a prosecutor was to find justice, I didn’t know it [guilty plea] was all about their own record and making themselves look good. The more cases a prosecutor wins the greater the chance they can be considered for higher office. The system encourages prosecutors to win by any means necessary… and they definitely do that by making up the rules as they go. It seems no one cares when prosecutors take actions that are worse than the defendant’s.”

According to Gramlich [44], only 2% of federal criminal defendants go to trial, and most who do are found guilty. The main benefit of plea bargaining is that it makes it possible for prosecutors to avoid costly, unpredictable trials. But at what cost? A deal requires either giving the accused something they want or ensuring that the alternative presented is so intolerable that they have no choice but to comply [45]. This results in lighter sentences for the guilty, at least for those who have information wanted by the prosecutor, and forces the innocent to plead guilty. Both situations result in an unjust conclusion. Another problem with plea deals, according to Turner [8], is that they are negotiated in private and off the record, resulting in a lack of transparency. Victims, the public and the defendant are typically excluded from the negotiations, which makes studying plea deals virtually impossible because the First and Sixth Amendments to the Constitution, addressing rights of public access, do not apply to plea negotiations [46].

Instead, plea deals are often made quickly, and given the lack of transparency, lies by both the prosecutor and the defendant are the norm [47]. When the accused is an opioid addict, plea deals become much more complicated, both legally and morally. During the period of time that a plea deal is normally negotiated, the opioid addict is embroiled in the excruciating pain of withdrawal and is cognitively confused with possible hallucinations. It is highly unlikely that these individuals are legally capable of entering into such an important, life-changing contract until at least a year has passed with no drugs. Once a deal is secured, the defendant forfeits the protections that come with a trial, such as an appeal, and can never declare they are not guilty. Crespo [48] argues that not only does plea bargaining operate in secrecy, but it also incorporates a third body of law, namely the sub-constitutional law of criminal procedure that establishes the mechanisms by which prosecutorial plea-bargaining power is both generated and deployed. These hidden regulatory levers are neither theoretical nor abstract but used in practice every day. As U.S. District Judge John Gleason observed in a 2013 ruling, the government’s use of certain draconian sentencing provisions during plea bargaining “coerces guilty pleas and produces sentences so excessively severe they take your breath away” [49].

Scott [9] writes of a prosecutor experience, saying, “Up to that point in my career, I was certainly aware of the vast power and discretion prosecutors possess in the United States criminal justice system. This phenomenon has been well documented in books and scholarly articles over the years. But it had not occurred to me that prosecutors could manipulate charges in response to political “hot button” issues in a way that created mandatory prison time for even the lowest, most impuissant players in the drug trade.” Prosecutors cannot be voted out of office and are rarely punished for their misdeeds. Providing a different perspective, Mallgrave [50] argues that the Commerce Clause limits the federal government’s authority to prosecute co-users who share the drugs that ultimately cause an overdose. Furthermore, by charging co-users with drug induced homicide, federal prosecutors threaten to derail local efforts to mitigate the overdose crisis. Prosecutors are not subject to civil liability for misconduct, not subject to professional condemnation and are rarely subjected to dismissal by the Attorney General of the state, or the U.S. Attorney General for federal prosecutors. Therefore, there are no incentives for prosecutors to restrain their behavior. State and local prosecutors often hold significant power and influence over local criminal justice communities; both judges and defense counsel are often concerned about the possible backlash from the prosecutor if misconduct is reported [21,22].

In certain situations, prosecutors have the power to challenge a judge’s ability to sit on criminal cases [51]. At the federal level, prosecutors have few limits. As the GS case highlights, federal prosecutors can: bring charges on real or imagined offenses, change sentences at random, threaten those charged, threaten family members of those charged, force guilty pleas, ignore evidence, silence judges, intimidate defending attorneys and deny constitutional rights. Academics and practitioners considering the problem of punishing prosecutorial misconduct agree that the disciplinary measures in place are grossly inadequate8. Most recognize that, although misconduct should not be tolerated, the lack of accountability results in implicit acceptance of wrongdoing. Caldwell [52,53] argues that to deter further misconduct and abuses of power, prosecutors must be punished more severely than attorneys who hold less distinguished and privileged positions. For example, prosecutors guilty of misconduct could be punished as willful perjurers and levied heavy penalties. Punishing prosecutors may help but the result could produce unintended consequences, just as it has with drug sentencing. In a 2018 report by the Brennon Center for Justice, specific examples of common-sense legislation are provided on topics such as: eliminating imprisonment for lowlevel crimes, reforming prosecutor incentives and making sentences proportional to crimes [54]. Ultimately, without a significant change in the attitude of the justice system as a whole, neither punishment of, nor changing incentives for prosecutors will be sufficient to bring about meaningful, lasting change [55-60].

Conclusion

Through the eyes of an addict and DIH federal prisoner, issues surrounding motive, addiction, minimum sentencing and prosecutorial misconduct have been brought into sharp focus. Similar to many other addicts, GS was convicted based on the prosecutor’s pronouncement that he would be tried as a dealer. However, the reality of being an opioid addict who is also capable of being a drug dealer is known to be false based on the cognitive and medical deterioration brought on by heavy use. To convict addicts based on being a dealer ignores the very real fact that they are cognitively incapable of performing such activities at any meaningful level. To prey on such people is both intentionally ignorant and cruel.

Mandatory minimum sentences are inconsistent with the principle of proportionality, which requires consideration of the merits of each case and a judgement that is exclusive to the defendant. In the 50 DIH cases reviewed for this study, there were no two cases that were exactly the same; each defendant had a unique criminal background, varying levels of culpability and diverse motives. Regardless of the goals for minimum sentencing, the policy has served to have an overall negative effect on the U.S.’s recovery from drug abuse. The continuation of increasing overdose rates, an increasing prison population and rising costs are evidence of the negative impact of the current and past approach. The continued pursuit of the punishment-revenge standard brings to mind the quote often attributed to Einstein: “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different result.”

Even without mandatory minimum sentences, the problem of prosecutorial overreach remains. In the case of GS versus USA, the right to a fair trial was skillfully denied and the right to the assumption of innocence until proven guilty in a court of law was never experienced at any stage of his arrest experience or throughout the proceedings. More importantly, due process was denied by ignoring the intent, or men’s rea, of the defendant as expressed by GS: “I could not separate the physical pain from the world around me and I lived and I suffered. I thought how could trying to help someone avoid this be so wrong. I really believed it was an act of kindness.”

References

- Carroll JJ, Ostrach B, Wilson L, Getty R, Bennett J, et al. (2021) Drug induced homicide laws may worsen opioid related harms: an example from rural North Carolina. International Journal of Drug Policy 97: 103406.

- Peterson M, Rich J, Macmadu A, Truong AQ, Green TC, et al. (2019) One guy goes to jail, two people are ready to take his spot”: Perspectives on drug-induced homicide laws among incarcerated individuals. International Journal of Drug Policy 70: 47-53.

- Beletsky L (2019) America’s favorite antidote: Drug-induced homicide in the age of the overdose crisis. Utah Law Review 2019(4).

- Center for Disease Control (2021) Drug overdose deaths in the US Top 100,000 annually. National Center for Health Statistics, USA.

- Koester S, Mueller SR, Raville L, Langegger S, Binswanger IA (2017) Why are some people who have received overdose education and naloxone reticent to call Emergency Medical Services in the event of overdose?. International Journal of Drug Policy 48: 115-124.

- Wagner KD, Harding RW, Kelley R, Labus B, Verdugo SR, et al. (2019) Post-overdose interventions triggered by calling 911: Centering the perspectives of people who use drugs (PWUDs). PloS one 14(10): e0223823.

- Banta Green CJ, Beletsky L, Schoeppe JA, Coffin PO, Kuszler PC (2013) Police officers’ and paramedics’ experiences with overdose and their knowledge and opinions of Washington State’s drug overdose-naloxone-Good Samaritan law. J Urban Health 90(6): 1102-1111.

- Varner H (2019) Chasing the deadly dragon: How the opioid crisis in the united states is impacting the enforcement of drug-induced homicide statutes. U Ill L Rev 2019: 1799.

- Scott LE (2019) Federal prosecutorial overreach in the age of opioids: The statutory and constitutional case against duplicitous drug indictments. U Tol L Rev 51: 491.

- Phillips KS (2020) From overdose to crime scene: The incompatibility of drug-induced homicide statues with dur process. Duke Law Journal 70: 659-704.

- Buikema J (2015) Punishing the wrong criminal for over three decades: Illinois’ drug-induced homicide statute. SSRN p. 31.

- Christopher JC, Hall Abigail R (2017) Four decades and counting: The continued failure of the war on drugs. Policy Analysis 811.

- Lamb HR, Weinberger LE (1998) Persons with severe mental illness in jails and prisons: A review. Psychiatric services 49(4): 483-492.

- Snoek A, Levy N, Kennett J (2016) Strong-willed but not successful: The importance of strategies in recovery from addiction. Addictive Behaviors Reports 4: 102-107.

- Health in Justice (2021) Drug induced homicides. Northeastern University School of Law, Massachusetts, USA.

- (2020) The science of drug use and addiction: The basics. National Institute on Drug Abuse, USA.

- Levy N (2011) Addiction, responsibility and ego-depletion. Addiction and Responsibility pp. 89-111.

- Lulzim Kupa (2013) United states district court, Eastern District of New York, USA.

- Mauer M (2010) The impact of mandatory minimum penalties in federal sentencing. Judicature 94: 6.

- Gilpin A (2012) The impact of mandatory minimum and truth-in-sentencing laws and their relation to English sentencing policies. Ariz J Int'l & Comp L 29(1): 91.

- Henning PJ (1999) Prosecutorial misconduct and constitutional remedies. Wash ULQ 77(3): 713.

- Jalain C (2021) Punishing the powerful: A study of prosecutorial misconduct in the era of ethics reforms. Scholarly Open Access Repository, Indiana, USA.

- Pitzer P (2013) Federal over incarceration and its impact on correctional practices: A warden's perspective. Crim Just 28: 41.

- Lewis N, Lockwood B (2019) The hidden cost of incarceration. The Marshall Project, USA.

- Wagner P, Bertram W (2020) What percent of the US is incarcerated? Prison policy initiative, USA.

- Lopez G (2017) Mass incarceration doesn't do much to fight crime. But it costs an absurd $182 billion a year. A New Report Suggests Mass Incarceration Costs Even More Than We Previously Thought, USA.

- Kang-Brown, Jacob, Montagnet Chase, Heiss Jasmine (2021) People in Jail and Prison in 2020. The Vera Institute, USA.

- Naqvi NH, Bechara A (2010) The insula and drug addiction: An interoceptive view of pleasure, urges and decision-making. Brain Structure and Function 214(5-6): 435-450.

- (2021) Fentanyl drug facts. National Institute on Drug Abuse, USA.

- National Institutes of Health (2020) White matter of the brain. US National Library of Medicine: MedlinePlus, USA.

- Joy PA (2006) Relationship between prosecutorial misconduct and wrongful convictions: Shaping remedies for a broken system. Wis L Rev 2006: 399.

- Diana W (2018) White matter disease. In: Han S (Ed.), Health Line, California, USA.

- National Institutes of Health (2015) Biology of addiction: Drugs and alcohol can hijack your brain. NIH News in Health, USA.

- Hudak J (2021) Biden should end America’s longest war: The war on drugs. Brookings, USA.

- Baillargeon JR, Penn JV, Thomas CR, Temple JR, Baillargeon G, et al. (2009) Psychiatric disorders and suicide in the nation's largest state prison system. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 37(2): 188-193.

- Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C, Colpe LJ (2017) Prevalence, treatment, and unmet treatment needs of US adults with mental health and substance use disorders. Health affairs 36(10): 1739-1747.

- Kolodny A, Courtwright DT, Hwang CS, Kreiner P, Eadie JL, et al. (2015) The prescription opioid and heroin crisis: A public health approach to an epidemic of addiction. Annual Review of Public Health 36: 559-574.

- Slate RN, Buffington-Vollum JK, Johnson WW (2013) The criminalization of mental illness: Crisis and opportunity for the justice system. 2nd (edn), Carolina Academic Press, USA.

- Regard M, Knoch D, Gütling E, Landis T (2003) Brain damage and addictive behavior: A neuropsychological and electroencephalogram investigation with pathologic gamblers. Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology 16(1): 47-53.

- Davis Gregory G (2013) Complete republication: National association of medical examiners position paper: Recommendation for the investigation, diagnosis and certification of deaths related to opioid drugs. J Med Toxicol 10(1): 100-106.

- https://www.drugs.com/drug-interactions/fentanyl.html

- (1887) Emerich’s letter to bishop Mandell Creighton. In: Figgis JN, Laurence RV (Eds.), Historical Essays and Studies, Macmillan Publishers, London, UK.

- Weintraub JN (2020) Obstructing justice: The association between prosecutorial misconduct and the identification of true perpetrators. Crime & delinquency 66(9): 1195-1216.

- Gramlich John (2019) Only 2% of federal criminal defendants go to trial and most who do are found guilty. Pew Research Center.

- Helm RK, Reyna VF, Franz AA, Novick RZ, Dincin S, et al. (2018) Limitations on the ability to negotiate justice: Attorney perspectives on guilt, innocence, and legal advice in the current plea system. Psychology Crime & Law 24(9): 915-934.

- Verdejo-García A, Bechara A, Recknor EC, Perez-Garcia M (2006) Executive dysfunction in substance dependent individuals during drug use and abstinence: An examination of the behavioral, cognitive and emotional correlates of addiction. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 12(3): 405-415.

- Neily C (2019) Jury empowerment as an antidote to coercive plea bargaining. Fed Sent’g Rep 31: 284-298.

- Crespo AM (2018) The hidden law of plea bargaining. Columbia Law Review 118(5): 1303-1424.

- Turner JI (2020) Transparency in plea bargaining. Notre Dame L Rev 96: 973.

- Mallgrave A (2020) Purely local tragedies: How prosecuting drug-induced homicide in federal court exacerbates the overdose crisis. Drexel L Rev 13: 233.

- Gershowitz AM (2008) Prosecutorial shaming: Naming attorneys to reduce prosecutorial misconduct. UC Davis L Rev 42(4): 1059.

- Caldwell HM (2013) The prosecutor prince: Misconduct, accountability, and a modest proposal. Cath UL Rev 63(1): 51.

- Caldwell HM (2017) Everybody talks about prosecutorial conduct but nobody does anything about it: A 25-year survey of prosecutorial misconduct and a viable solution. U Ill L Rev 1455: 33.

- Schoenfeld H (2005) Violated trust: Conceptualizing prosecutorial misconduct. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 21(3): 250-271.

- Crews FT, Boettiger CA (2009) Impulsivity, frontal lobes and risk for addiction. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior 93(3): 237-247.

- Freeman PR, Hankosky ER, Lofwall MR, Talbert JC (2018) The changing landscape of naloxone availability in the United States, 2011-2017. Drug and alcohol dependence 191: 361-364.

- Jacques S, Allen A, Wright R (2014) Drug dealers’ rational choices on which customers to rip-off. International Journal of Drug Policy 25(2): 251-256.

- Andrea J, Hillary VK, Zina HR, Anne S (2018) Knowledge of the 911 Good Samaritan Law and 911-calling behavior of overdose witnesses. Substance Abuse 39(2): 233-238.

- National Survey on Drug Use and Health (2000-2020) Substance abuse and mental health services administration, USA.

- Priya R (2018) Criminal justice solutions model state legislation. The Brennon Center, New York, USA.

© 2023 Hancock GD*. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)