- Submissions

Full Text

Novel Research in Sciences

The Role of a Therapeutic Garden in the Dementia Ward in a Teaching Hospital in Singapore

Si Ching Lim1*, Vivian C Barrera1, Lim Huiru2, Anna Liza P Bantillan2

1Department of Geriatric Medicine, Singapore

2Department of Nursing, Singapore

*Corresponding author:Si Ching Lim, Department of Geriatric Medicine, Changi General Hospital, Singapore

Submission: December 14, 2022;Published: January 09, 2023

.jpg)

Volume13 Issue2January , 2023

Abstract

The elderly patients living with dementia get admitted frequently to the acute hospitals for a variety of medical problems. Taking care of this group of vulnerable adults is challenging for the care team as they have higher care needs and miscommunication often occur resulting in unmet needs which may cause frustrations for both the patients and the care team. Designing therapies to keep the patients actively engaged is beneficial for both the patients and the care team. Contact with nature is increasingly studied as an effective method to manage stress. The presence of therapeutic gardens in an acute hospital ward could be a promising therapeutic intervention for work related stress for the hospital staff, while providing garden therapy for patients living with dementia.

Keywords: Therapeutic garden; Acute hospital; Hospital staff; Stress management; Dementia

Introduction

Singapore is rapidly ageing, currently the elderly >65 make up 18.4% of the total population, compared to 11.1% a decade ago in 2012. By 2030, a quarter of the population will be aged >65 [1]. The local data showed that there are around 92,000 individuals living with dementia currently, and this number will increase to 152,000 by 2030 [2]. The elderly Persons Living With Dementia (PWD) are more likely to be hospitalised due to their multiple comorbidities, polypharmacy, functional dependency and older age [3]. The elderly PWDs are more likely to be admitted for falls, fractures, respiratory and urinary tract infections, compared to the elderly persons without dementia [4]. Once admitted, they are likely to stay longer and develop complications during the hospitalization, adding to the existing medical and psychosocial problems for which they were admitted. The common hospital acquired complications included delirium, infections, dehydration, decline in physical/cognitive function and the mortality was higher [5]. While the elderly PWDs were admitted in an acute hospital, they are more likely to be physically restrained, particularly if the agitated or restless patients are at risk of falls or pulling out medical devices. Physical restraints cause poor outcome for the frail elderly PWDs by limiting their autonomy of movement. The enforced immobility increased risks of delirium, pressure injury, urinary retention, constipation, depression, etc [6,7].

In the author’s hospital, >60% of the hospital’s 1100 beds are occupied by an elderly >65 at any one time. Among these elderly inpatients, about 40-50% have cognitive issues. The majority of the confused elderly inpatients were living with dementia which had not been formally diagnosed. The hospital has a 20 bedded dementia ward which is catered for the elderly with cognitive impairment exhibiting difficult to manage behavioural symptoms. The ward has a restraint free policy, unless there are no other alternatives available for managing the behavioural symptoms, or the patients are at risk of harming themselves or others around them. The care team adopted a Person Centred Care (PCC) model for all the patients, in order to manage the behavioural symptoms non-pharmacologically in a restraint free environment. In order to practice PCC, the care team get to know their patients’ psychosocial as well as their medical background. The care plans are individualized, taking into account the PWDs’ personal preferences, routines and current cognitive function.

The author’s team explored the idea of therapeutic gardens as a potential therapy to keep the patients actively engaged during their stay. The availability of green spaces within an acute hospital ward, with free access to staff and patients is a novelty in the local setting. The authors believe that contact with nature, albeit brief, provides a short respite from work stress. There are data available to suggest benefits of therapeutic gardens in managing behavioural symptoms of dementia, but the publications were in long term care setting.

Aim

The study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of therapeutic garden in an acute hospital setting as an additional therapy to the standard therapy available for patients with dementia. The study’s hypotheses are there are no benefits of having therapeutic gardens in an acute hospital, the gardens made no difference the working staffs’ stress levels and has no effects on the patients’ behavioural symptoms.

Methodology

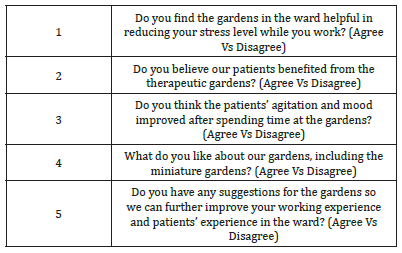

A qualitative approach explored the ward staffs’ experience in using the gardens as a therapeutic modality for the elderly patients with dementia in the dementia ward. The ward staff included nurses, doctors, allied health professionals, patient service associates, cleaners and administrative staff. The dementia ward has a wide range of therapies on offer and are routinely offered to the patients based on their individual interests and cognitive abilities. The conventional therapies available in the ward included doll therapy, robotic pet therapy, music therapy, exercises, art and craft, multisensory stimulation with the aids of sensory aprons, sensory pillows and sensory trees. The therapeutic gardens are new additions to their usual activities. (Figure 1-3) The gardens are used as therapy areas during breakfast and afternoon tea times. The patients may continue to be seated in the gardens after their meals for simple seated exercises, art and craft, music therapies, etc. More active therapies at the garden included watering the plants, touching and smelling the flowers/ herbs and reminiscence therapy while the patients talked about their experiences with gardens in their past. In addition to the colourful plants, there was a MP3 with recording of nature’s sound like waterfalls, dog barking, rooster clucking, birds chirping and cats meowing. The MP3 is turned on during these therapy sessions at the gardens. The sound of nature brings the patients back to their younger days of living in a village, which transforms the patients away from their hospital sick beds. Scattered throughout the ward are miniature gardens in glass bottles and small water fountain with colourful decoration. (Figure 4-6). Data collection was done using a survey form which consisted of 5 questions. (Table 1) Data collected included staff’s perception of the gardens in reducing their stress levels while at work, patients benefiting from the therapeutic gardens with improvement in agitation and mood, the uniqueness of the ward by incorporating nature as an adjunctive modality for healing. The ward staff were encouraged to answer the survey forms anonymously, under no duress.

Figure 1:Therapeutic gardens with various tropical plants, visual stimulation with colours, tactile stimulation with various textures of the different plants, sense of smell from the flowers and herbs.

Figure 2: Small collection of herbs found locally like curry leaves, oregano, rosemary in the garden.

Figure 3:Small statures holding miniature plants.

Table 1:Survey form for the ward staff.

Figure 4: Miniature garden in a glass jar with colourful decorations.

Figure 5:Miniature garden in a flower pot shaped like a boat. The wording symbolize smooth sailing.

Figure 6: Small water fountain and miniature garden of cactus plants and succulents.

Results and Discussion

There were 37 responders for the survey. There were 3 themes which emerged from the thematic analysis from the staffs’ perception of the therapeutic gardens in the dementia ward. Among the staffs who answered the survey, 65% felt that the therapeutic gardens were helpful in reducing their stress levels while they were working in the Dementia Ward. The remaining 35% were neutral. The average time spent in the gardens outdoor was 30-45 minutes per session. Among the patients who were able to participate in garden activities, or sat out in the garden for meals and activities, 95% gained benefit for being outdoors in contact with nature. The staff felt that 84% of the patients showed an improvement in their behavioural symptoms such as agitation and mood after the session at the gardens. The remaining 16% remained agitated. The MP3 recording of nature’s sound was an extra feature which augmented the sense of being in contact with nature, away from their sick beds.

Theme 1- Beneficial Contact with Nature

The staffs reported “feeling refreshed” having 2 gardens for them to look at, engaging their patients with gardening activities or a gentle stroll with their patients. While the nursing staff serve breakfast and afternoon teas at the gardens followed by activities for the patients, they “had a break from the indoor hospital scenes,” for “a short respite of fresh air; looking at the colourful and beautifully arranged plants.” The nurses took pleasure looking and tending to the plants while the patients ate their meals. In this current era where technology has invaded our work and personal lives, most people spend the majority of their days looking at a screen. Contact with nature is decreasing, especially with the global trend of urban living. The biophilia hypothesis argues that human have an innate drive to connect with nature since our ancestors depend on nature for their livelihoods [8]. Contact with nature can either be active gardening activities or passively such as walking along or simply sitting in the gardens.

Healthcare industry has invested a lot in going electronic for documentation to reduce errors and ensure consistency and transparency. Working in the hospital involve spending long hours staring at a screen for all the staff, with short, interrupted breaks during the working hours. Exposure to nature has been long known to be associated with cognitive benefits, mental and emotional well-being. Contact with nature has been shown to improve cognitive performance among children and adults. Among the cognitive domains studied, attention, working memory and cognitive flexibility were shown to improve with greater exposure to natural environments. Contact with nature, albeit brief, improved the attention span and work performance among adults and children[9].

The staffs who gave neutral responses to the green spaces were probably too busy to even slow down to appreciate the green spaces. The acute hospitals have been overstretched for the last few years since the beginning of the COVID 19 pandemic. Although the pandemic had deescalated to an endemic phase, rapid turnover had been the norm to cope with the increased patient load. In a hospital ward where cleanliness and tidiness are always top priorities, to have room for green spaces is a refreshing change. For the patients, it is a pleasant surprise to have greenery attached to the vicinity of their beds. One of the patients commented that he was fortunate to stay in the dementia ward, with a pleasant view of the garden near his bed. Spending time at the garden was a break for him away from his worry about his medical conditions. His contact with the green spaces was spending time just by being outdoor, walking and admiring the plants. His experience was so refreshing he felt that green spaces should be encouraged in all the hospital wards.

Theme 2- Reduction in Stress Level

The staffs commented it is “stress relieving having green spaces in the hospital ward.” Having beautiful and colourful plants to look at while they were busy at work is relaxing, refreshing and makes them feel happy.

Stress is now classified by WHO as the “Health epidemic of the 21st century”. Under managed stress is a risk factor for various cardiovascular, musculoskeletal and mental disorders. Psychological stress was linked to mortality risk due to cardiovascular diseases and cancers [10,11]. Work related stress is increasing over the years, especially in the last few years as the world lived with the COVID 19 pandemic. Font line workers have been well documented to suffer from burn out and ill-health [12,13] .Work place related stress will likely increase in the future due to higher demands and lower job security. Managing stresses arising from work and personal life may be overwhelming for some people. Approach to stress management includes muscle relaxation, cognitive behavioural skills and a combination of these techniques [14] . In recent years there has been increasing interests on using nature, music, dance, and arts as interventions in stress management.

Spending time with nature triggers a positive emotional response which allows the person to return to an un-stressed state. Spending just 10 minutes a day, three days a week is shown to reduce cortisol level. In a study from the US, the subjects had no specific tasks to perform while spending time in the yard or public parks or green areas near their work place. The activities could be simply walking or sitting in the green places. The beneficial effect of nature was shown to be effective by reducing salivary cortisol levels, and the effectiveness of nature in reducing stress was greatest between 20-30 minutes of time spent in the green spaces [15]. There is increasing interest to prescribe nature as adjunctive treatment to improve mental and emotional well-being. The “nature pill” is gaining popularity but little is known about dose response. Studies are needed to advise on duration, frequency and intensity of exposure, as well as the setting for therapy, such as natural settings or any green spaces available [15]. In addition to contact with nature and plants, the miniature gardens in the ward were attractive pieces of art work. The staff described them as “colourful, cute, nice and pleasing to the eyes.” The staff also commented that these “miniature gardens are captivating and beautiful decorative pieces in an otherwise dull environment.”

Theme 3- Better Engagement and Reduction in Agitation

While not all the patients were suitable to be wheeled outdoors for meals in the gardens, the patients who spent time in the gardens had better mood and their behavioural symptoms improved, especially a reduction in agitation. The staff noted that the patients were “actively engaged in gardening activities,” “patients felt more energetic,” “actively conversing about the various plants and herbs.” Taking care of an older person with dementia is often challenging for the care team, especially if the person has difficult to manage behavioural symptoms. In the acute hospital setting, the older Persons Living With Dementia (PWDs) are often left on their own without structured activities during the day. Hospital admissions are unfortunately common among the elderly PWDs due to their complex comorbidities, polypharmacy and fall risks. Once admitted, they tend to stay longer and acquire complications like falls, delirium and incontinence. Restraint use is frequent to reduce falls and injury risks among this group of patients, with undesirable outcomes like cognitive and functional decline [16].

Person Centred Care (PCC) model has been recommended as the preferred care for the PWDs. PCC has been shown to reduce psychotropic medication usage and improvement in behavioural symptoms. Unfortunately, it is challenging to implement PCC in an acute hospital setting as the turnover rate is high and staffing level may not be consistent [17]. In the dementia ward, PCC has been the routine since opening its doors. The care plans included a variety of therapies to keep the patients engaged cognitively and socially. Despite the restraint free policy, fall rate has not been high and most of the patients were discharged back to their own homes. The therapeutic gardens will be a refreshing change as a venue for patients to have their meals and conduct therapies [18]. They were suggestions to design more green spaces in the hospital, especially for the patients on palliative care. Ideally, the patients can get more actively engaged with planting and harvesting. However, since this is hospital setting, strict adherence to infection control measures should be obeyed.

Positive Quotes

a) “We get to be in close contact with nature in a busy

hospital environment.”

b) “The colourful plants are beautifully arranged and so

pleasant to look at.”

c) “Gardens are so refreshing and inviting.”

d) “The plants are cute, colourful, pretty and captivating.”

e) “Very therapeutic work environment.”

f) “Very soothing to stare at.”

g) “Reduces stress levels, especially for the staff.”

h) “Looking at flowers and greens make me feel happy.”

i) “Patients were engaged in helping with watering the

plants.”

j) “Patients felt more lively while they were in the ward

looking after the flourishing plants.”

Barriers Observed

There were barriers to the therapeutic gardens. There were

staff who did not notice their presence, did not appreciate the

beauty of nature. Even though the gardens were freely accessible,

not all the patients got to experience the beauty. The patients were

wheeled outdoors in their geriatric chairs. For those who had active

infectious disease, or patients who were not able to sit or too ill to

be out of bed, they were not taken outdoors for their meals.

Negative Quotes

a) “The gardens do not help all patients, only some.”

b) “Gardens have no effect on me, attract mosquitoes.”

Limitations of the Study

The sample size is small, and the study duration was short. Perhaps a longer term observation is helpful to assess challenges in maintaining vibrant gardens in a hospital ward, patients’ perception of the benefits and the longer term effects of contact with nature for the ward staff.

Conclusion

As the elderly patients continue to grow, the traditional model of care has not been the ideal for the elderly patients with dementia. Therapies aiming to get patients engaged physically, cognitively and socially should be the norm in order to prevent risk of cognitive and functional decline during the hospital stay. It is however challenging to plan activities and motivate the patients to get out of bed. Gardening and nature are familiar to everyone and having a walk in the green spaces are relaxing and enjoyable. It is unusual to have gardens in the vicinity of an acute hospital ward, and it is most encouraging to see the positive effects the gardens have on the staff and patients and their caregivers.

Acknowledgement

The team would like to acknowledge the kind contributions from Madam Jessie Ang and the Dementia ward’ staff for their dedication and commitment. Without them, this project would not have matertialise.

References

- (2022) The Straits Times.

- Towards a dementia-inclusive Singapore.

- Hilary S, Gill L, Justin C, Andrew S (2019) Hospitalisation rates and predictors in people with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 17: 130.

- Sandeep T, Mike D, Ajiri A, Martin O (2013) Causes of hospital admission for people with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JA m Med Dir Assoc 14(17): 463-470.

- Carole F, Peter G, Paul M, Jackie B (2018) Hospital outcomes of older people with cognitive impairment: An integrative review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 33(9): 1177-1197.

- Krüger C, Mayer H, Haastert B, Meyer G (2013) Use of physical restraints in acute hospitals in Germany: A multi-centre cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud 50(12): 1599-606.

- Silvia T, Sandra Z, Dirk R, Silvia B, Sabine H (2021) Restraint use in the acute-care hospital setting: A cross-sectional multi-centre study. Int J Nurs Stud 114: 103807.

- Wilson EO (1984) Biophilia, Harvard University Press, USA.

- Kathryn ES, Marc GB (2019) Understanding nature and its cognitive benefits. 28(5): 423-517.

- George Fink (2016) Stress: concepts, cognition, emotion and behaviour. Imprint: Academic Press, pp. 502.

- Russ TC (2012) Association between psychological distress and mortality: Individual participant pooled analysis of 10 prospective cohort studies. BMJ 345: 4933.

- Barrera V, Sigaya KV, Espeleta WD, Tanya Q, Ching L (2020) Examining nurses’ well-being while caring for the elderly in pneumonia acure respiratory infection ward. Ann Clin Med Res 1(4): 1017.

- Gabriele G, Luigi IL, Federico A, Georgia LF, Giorgia B, et al. (2020) COVID-19-related mental health effects in the workplace: A narrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(21): 7857.

- Lawrence RM (1996) Stress management in work settings: A critical review of health effects 11(2): 112-35.

- Mary RH, Brenda WG, Sophie C (2019) Urban nature experiences reduce stress in the context of daily life based on salivary biomarkers. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 722.

- Jim G, Susannah L, Charles V (2013) How can we keep patients with dementia safe in our acute hospitals? A review of challenges and solutions. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 106(9): 355-361.

- Sam F, Sheryl Z, Patrick JD, Emily S, Molly C, et al. (2020) What is really beeded to provide effective, person-centred care for behavioural expressions of dementia? Guidance from the alzheimer dementia care provider roundtable. Journal of the Americal Medical Directors Association 21(11): 1582-1586.

- SC Lim (2017) The role of a dementia ward in an acute hospital. J Gerontol Geriatr Res 6: 6.

© 2023 Si Ching Lim. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)