- Submissions

Full Text

Novel Research in Sciences

The Transition to Automated and Virtual Medical Care for Geriatric Patients

Madison Forehand, Kevin Sneed and Yashwant Pathak*

Taneja College of Pharmacy, Judy Genshaft Honors College, University of South Florida, USA

*Corresponding author: Yashwant Pathak, Taneja College of Pharmacy, University of South Florida, 12901 Bruce B Downs Blvd, MDC 030, Tampa FL 33612, USA

Submission: August 9, 2022;Published: October 19, 2022

.jpg)

Volume12 Issue2October , 2022

Abstract

Geriatric patients, 65 years of age and older, are constantly affected in ways far removed from those of patients with more mobility and less afflictions. The population of geriatric patients is exponentially growing and the number of providers is not, leading to a gap that can be partially remedied by telecommunication. The pandemic forced providers to virtually connect with patients for a variety of reasons, but this in and of itself is a potential opening for greater digitization of healthcare for geriatric patients.

Automated and virtual medical care, referred to as telehealth or telemedicine in this paper, is the usage of electronic devices to provide medical attention to patients remotely. Technology dependence and a lack of technological competence in the older generation are the main concerns of transitioning; however, many of the hurdles posed are easily overcome or prepared for, making advantages such as lower costs and increased ease of access to a medical provider the driving force behind converting to telemedicine. This article will attempt to inform on the history of geriatrics, why the transition to virtual medical care is occuring, and the positives and the negatives of this transition, in addition to ways to solve the obstacles posed.

Keywords: Acute respiratory distress syndrome; Cardiology; Respirat

Introduction

Covid Impact on the elderly

Adapting to a world where lock-downs and risk of infections prevent in-person medical treatment has brought about many transformations to the medical field. As with all viruses and diseases, certain demographics of the population pose a higher risk of contraction and varying illness severity. The demographic most susceptible to the coronavirus is the elderly population, who are more likely to suffer severe illness and a higher rate of mortality due to underlying diseases and injuries that increase vulnerability [1].

Advancing age coincides with deterioration of the health of vital organs and their physiological response to disease. As health declines, respiratory and cardiovascular diseases known to have a positive correlation with the risk of contraction and possible death from COVID-19 develop. A study of 56 patients with a COVID-19 infection, 18 of whom were categorized as elderly, found that the presence of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) and acute kidney, heart, and liver injuries were higher for the elderly group than the young and middle-aged groups. Additionally, 12 of the 18 elderly patients had basic chronic diseases such as diabetes and/or cerebrovascular and cardiovascular disease, a significantly higher proportion in comparison to the young and middle-aged group thus indicating that COVID-19 is more likely to infect elderly patients that express the presence of chronic comorbidities due to a weakened immune function [2]. Furthermore, a different study analyzing over fourthousand confirmed coronavirus cases found that the mortality rate of the 1,052 patients aged 60 years old and up was 5.3% a notable difference from the 1.4% mortality rate of the remaining patients under 60 years of age [3].

Compromised immune function in elderly patients increasing susceptibility to contraction and heightening the risks posed by COVID-19 has consequently led to geriatric medicine making a mass transition to virtual and automated medical care for its patients’ well-being.

What are geriatrics

The field of geriatric medicine differs from most other specialties in that it focuses not on systems (i.e. cardiology, immune system, respiratory, etc.), but instead on the process of aging, similar to pediatrics. Geriatric patients are primarily of ages 65 and older and care is directed towards the implications of their agingsuch as the deterioration of their cognitive and physical functions along with the coinciding morbidity. Treatment and care is unique to the individual person and their issues while also considering the patient’s environment; with this information, the physician’s goal is to provide the highest quality of life for the patient’s remaining days or years [4]. However, predictions propose that within the next 30 years the number of geriatric patients will more than double potentially leading to a scarcity of geriatricians available to treat patients-a population already suffering from the lowest functionality and the highest levels of morbidity [4,5], Fortunately, the transition to virtual medical care allows for physicians to reach more patients that may lack access to a medical care facility.

To improve the health and well-being of geriatric patients, the

American Geriatrics Society (AGS) Task Force established five goals

for the field to assist in realizing their mission.

These goals include:

a) Ensuring the highest quality, patient-centered care for

every older person.

b) The expansion of the knowledge base for geriatrics

c) Growing the number of health professionals that utilize

geriatric principles in their care

d) Increasing the number of geriatric physicians

e) Lobbying for public policy that will continuously advocate

for the health care of seniors [6].

While it is not uncommon for geriatricians to have subspecialties in areas of interest or strong need, interprofessional between these physicians and other areas of the medical field and health professions is necessary to ensure the optimal medical care for elderly patients. There are various areas to consider when providing care to a patient and the ability for geriatrics to give consistent, and still high quality, care in all those areas is becoming increasingly more of concern. By sharing medical care with other practitioners specialized in alternative fields, the patient receives more effective medical attention [7]. With electronic health records, patient information can be shared across all healthcare systems as well as within individual systems, meaning that each provider of a patient has corresponding knowledge with each other, reducing the likelihood of patient misprescriptions that may lead to unsafe drug interactions and/or incorrect dosages [6].

Virtual and automated medical care

The transition to automated and virtual medical care was essential to all medical practices in light of the Covid-19 pandemic but was specifically highly beneficial to the geriatric population as it increased the deliverance of timely care while minimizing the potential of exposure for both patient and practitioner. That as it may be, the quality of and ability to provide adequate and accurate virtual medical treatment is dependent on both the physician and patient being knowledgeable on how to operate the technology and platforms used, in addition to the quality of the video and images used for diagnosis [8]. Additionally, advances in telecommunication in the medical field especially improves the quality of the health care system in rural communities as it allows for the distribution of expertise in areas where and when it is needed [9]. Overall, transitioning to automated and virtual medical care has many positive aspects, but similarly has disadvantages that must be considered and addressed for practitioners to provide the most beneficial care possible.

Main Body

The history of geriatrics

Old age has been with us since the beginning of human existence. The young and the elderly are given medical care by specialized physicians-pediatricians and geriatricians, respectively. Yet, despite the numerous advancements in medicine and human existence being synonymous to the presence of these age groups, it is only within the last century that the field of geriatric medicine came into being. Throughout this time period, geriatrics underwent extensive development and it continues to improve with the acquisition of knowledge as it adapts to an ever-changing world.

Humanity has been enamored with the idea of overcoming death and reversing the process of aging for thousands of years. The ancient Egyptians were quite knowledgeable about the afflictions associated with the onset of age, as were the Greeks; unfortunately, as many civilizations still blamed these disabilities on myth and superstition, their elders were often supplied with inaccurate and inadequate medical treatment. During the twentieth century, Nobel prize winner, Elie Metchnikoff, known for his theories that invoked extensive research in probiotics to treat disease, coined the erroneous term ‘gerontology’ for the studying of aging; however, the prefix ‘geronte’ is French for man and so the term ‘gerontology’ really means the study of old men. The correct term would be geratology [10].

Although American pharmacist Ignatz Leo Nascher is ascribed with the birth of modern geriatrics, owing to his invention of the word ‘geriatrics’, it is British Dr. Marjory Warren and her constituents who are credited with its development [10]. Working at West Middlesex County Hospital, Dr. Warren cared for several hundred patients, primarily old and infirm, through a system of classification that matched care to the patient’s needs. Both in and outside of the ward, she was incessant about improvements to her field that would bolster the determination of patients and staff, and through her papers, Dr. Warren advocated for the creation of a medical specialty in geriatrics, the continuation of the practice of geriatric medicine through the instruction of elderly care by specialized practitioners to medical students, and the addition of geriatric units to all hospitals. Many people came to observe her practices, and because of Dr. Warren and her constituent’s achievements, the British Geriatic Society was established in 1947 and in the following year-the first geriatric consultants were appointed to the National Health Services (NHS) by the Ministry of Health; in America the American Geriatric Society was established a few years earlier, on June 11, 1942 [11].

Unfortunately, in recent years, due to the aging of the Baby Boomers (titled so due to the exponential growth, or ‘boom’, in the number of babies that began their generation which is the largest living generation), the geriatric population has increased considerably and it is estimated that 20% of the American population will be 65 years or older by 2030. This surge in the elderly population is already taxing the health care system, as this population requires the most continuity of care across multiple specialities in part because of their decreased functionality and a higher prevalence of chronic conditions [12]. To address the coinciding challenges, geriatric physicians worldwide are working on ways to provide the best care through multidisciplinary teams and by addressing areas of modern medicine that are problematic for old patients. Elderly patients most always exhibit concurrent health problems that span across multiple domains and, therefore, the implementation of multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) allows for a comprehensive assessment of the patient from various professions able to address the different domains. The goal of a multidisciplinary team is to set up patient-centered goals by covering not only the domain of medical problems, but also cognitive and physical functionality in addition to their social environment. Once each domain is addressed, the team can come together to create a goal and a plan to achieve it - reconvening regularly to evaluate progress [13]. This holistic approach results in a more comprehensive assessment of the patient and consequently more effective medical attention that can help overcome the problems of diagnosis priority, medical care compensation, and the medicalization of simple daily living [14].

The future of geriatrics relies on continuous improvement and modification to enable its physicians to provide the best care for its patients. The field of geriatrics isn’t a one-size-fits-all medical treatment but requires the consideration of many factors for proper diagnosis and care. Its basic function is to act as chronic disease care for the elderly but cannot stand on its own. Additionally, for the geriatric field to truly reach its utmost potential, physicians must encourage and engage their patients into taking an active part in their own care by being more proactive in communication and tracking of their problems [15]. As the geriatric population grows, geriatricians providing primary care will have to develop teams sharing care with specialized physicians who can help this field keep up in an ever-changing world.

Pros of transitioning to automated and virtual medical care

The transition to automated and virtual medical care (telehealth/ telemedicine) began farther back than most people realize, but doctors were quite aware of its benefits. If not life threatening or urgent, many visits to a doctor’s office can be eliminated, and that is exactly why physicians first used the telephone starting in 1879. However, with the development of technology and telehealth, physicians now generally use video calls to interact with patients, allowing them to see their patient, not just hear them. A good deal of data has shown that telehealth conferences are just as beneficial and comparable to in-person visits, with the upside being that the older patient can do it from the comfort of their home. Additionally, the transition to virtual medical care means that if a medical issue arises in an older patient, they are able to communicate with a health professional much quicker. Telemedicine can be used to reach older patients in rural communities, far from access to a physical office, and it has been shown to decrease visits of the elderly in senior living communities (SLCs) to the emergency department (ED). Overall, in-home telehealth programs have many benefits and can be used for rehabilitation and improving the quality of life of older patients with stable chronic conditions or suffering from geriatric syndromes or cognitive impairment [16].

While telemedicine for geriatric patients is not all that different from telemedicine for other patients, it does offer some specific benefits. The first and most advantageous benefit being that telemedicine allows for elderly patients to maintain their independence and for their physicians to recognize problems early on in their development, all while the patient remains in the safety of their home [17]. Simple monitors can be used to track and analyze patient activity, sleep, oxygen saturation, blood pressure, and pulse, thus reducing the number of demanding regular visits to a doctors office through constant non-invasive surveillance. Additionally, by reducing the number of visits taken, the cost of medical care is significantly reduced as visits will only be had when of the utmost necessity, but cost is also reduced by another advantage of transitioning to virtual medical care - storage of patient information. Digitally storing patient data reaps its own benefits in regard to interprofessional communication but combined with the advances in technology making live transmissions simpler and cheaper the transition makes the issues of access and cost easier to overcome.

Furthermore, with geriatrics being a field requiring the overlap of other specialities, storing patient data digitally allows for access across all healthcare systems meaning all providers, both specialists and geriatrician, are all in accordance with each other. Telecommunication also helps support this collaboration because both the geriatrician and specialist can be in the virtual meeting with the patient so both know what is transpiring and can create a plan best suited for the patient. Because of the relationship built between all three parties it has been shown that there was improved patient care [18]. In regard to senior living communitie (SLCs), a study was conducted observing 503 patients engaged in telemedicine visits; 362 patients engaged in a higher-intensity SLC and 141 in the lower-intensity SLC. The results found that the more engaged SLC experienced a 28% reduction in the number of emergency department (ED) usage, while the control group and the less engaged group showed no marked change in usage. This may be due to the increased involvement of both nurses and patients in those communities meaning there is more active participation in the well-being and care of the patient, but there is nonetheless a positive correlation between usage of telemedicine and reduction of ED USA In conclusion, transitioning to virtual medical care reaps many benefits for both the patient and the practitioner. The patient is able to receive medical attention quickly if necessary due to telemedicine’s whole objective of physicians being available anytime for anything [19]. Medical treatment is more effective because geriatricians are able to communicate with specialists and create a plan of care best suited for the patient. Geriatricians are able to reach more patients, especially ones that have low mobility and can’t leave their homes because they are able to meet via a virtual conference, plus virtual monitoring allows for physicians to know when a patient needs a visit rather than just scheduling an unnecessary check-up.

Cons of transitioning virtual medical care and their solutions

For every positive there is also a negative, and while telemedicine has many benefits it also has a few disadvantages. These drawbacks include, but are not limited to, technical difficulties and lack of technological competence, deficiencies in security, comprehensive physical examinations via teleconference have many limitations, and difficulty implementing in low-income countries. Additionally, there are many regulations and rules that healthcare providers have to hurdle, varying from location to location creating confusion and unclear guidelines for medical organizations [17].

To begin with, the most striking disadvantage would be the safety of telemedicine in regard to storing patient data and platforms used for virtual appointments. This is increasingly of concern as cyber-attacks on medical information have become more common and are growing at a rate of 22% a year. Just in 2015, 112 medical records were compromised [20]. Telemedicine risks the privacy of patient information and costs the healthcare industry about 380 USD (United States Dollars) per lost or stolen record, summing up to a total $67 billion spent dealing with security breach issues [21]. This particular issue can be overcome by the implementation of security measures such as identification numbers unique to each user, education of providers on safety precautions to mitigate breaches should one occur and protect their clients, utilization of a privacy self-assessment by telehealth professionals, data backup, and encryption and decryption [22]. With adequate preparation, this issue can be easily addressed and reduce the likelihood of an issue arising.

However, another important issue to address is the limitations of performing a thorough physical examination through a screen. Video examinations are challenging for both the patient and the provider, as the patient must navigate tasks they aren’t necessarily equipped or skilled to do accurately and to perform these assessments so that it is visible to the provider as well. On top of this, the physician then must determine if the assessment was adequate and reliable [23]. Fortunately, with telemedicine being available whenever and wherever, if an issue arises after a teleconsultation the patient can quickly reach a medical provider to find a solution or render a new diagnosis. The provider can use telehealth to monitor the patient’s progress and clear any miscommunication and unclear instructions about a treatment plan [24]

The transition to virtual and automated medical care also requires the consideration of possible technical difficulties and technological incompetence. Much of the elderly population is unfamiliar with and has stigmas against technology, which can negatively impact their usage of technology and thus their ability to receive virtual medical care. Frontiers in Psychology published a study finding that the stigma could be caused by lack of confidence, knowledge, instruction, and guidance towards using technology, and hurdles in regard to health [25]. These obstacles can be easily remedied through the education of elderly patients in the usage of technology. A study of participants aged 65 and older, found that after 5 weeks of a training program on Internet health retrieval and usage, participants expressed lowered levels of anxiety and increased confidence and self-efficacy in comparison to those that did not participate in the program [26]. A different study was performed in which 54 geriatric aged adults were trained on the usage of iPad for three months and it found that such training not only provided older adults with useful technological skills, but also improved their cognitive function [27]. Conquering technological incompetence through training and education is simple and beneficial to the patient and only costs the patient time.

Finally, implementation of telemedicine in low-income and developing countries can prove difficult as the government is usually involved in the transition to virtual medical care and they may not have many of the resources and/or access to the technology to make such a transition. For these countries to establish a strong telehealth system, they must consider the applications of the transition and the environment, culture, economy, and the needs of the country in which it will occur [28]. Once telehealth gets a foothold in these countries, their population will begin to flourish as more people are able to receive medical attention, greatly benefiting their society and causing it to develop even more [29-31].

Conclusion

All things considered; geriatrics has progressed quite a lot seeing as it only came into being around the last century. The field of geriatrics is constantly evolving as the world changes and differs from other medical fields in that each case in geriatrics is unique. A patient’s diseases, chronic conditions, and environment require consideration during the formation of a plan for treatment and care that cannot be one-size-fits-all. With the growth of the geriatric population, geriatric physicians must learn to work in teams with other specialized medical professionals, to provide the most effective care for their patients. This became prioritized with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the elderly couldn’t go to in-person appointments but still needed care and so the transition to automated and virtual medical care began. Transitioning to automated and virtual medical care for geriatric patients procures benefits and disadvantages that can also be applied to other medical fields and age groups. The transition minimizes exposure to the coronavirus for both the patient and physician and allows for people without immediate access to a physical healthcare facility the opportunity to receive medical attention quickly. This is especially important for the elderly demographic as they are the most compromised age group health wise and suffer from the lowest mobility and physical functionality.

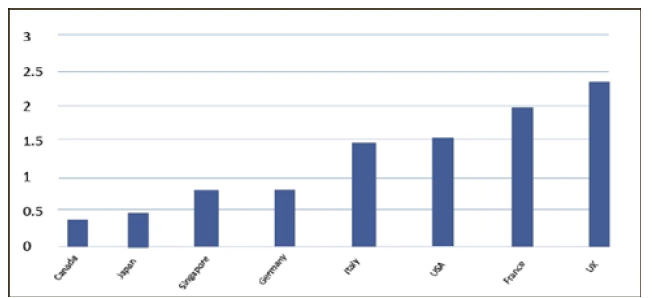

Figure 1: Number of geriatricians to a population of 10,000 people 65 years and older.

Although the transition does have a few downsides, such as elderly patients being technologically challenged and breaches in medical security, they can be easily remedied and prepared for. With training and education, older people can overcome their lack of knowledge and confidence in using technology while simultaneously improving their cognition. Potential security issues and cyber-attacks can be prepared for by utilizing safe platforms for record storage and telecommunication between patients and providers and by creating a plan for if such a problem should arise. Geriatrics will continue to develop and change with advances in technology and developments in patient diseases and conditions. Who knows where the future of geriatrics may lead?.

Future Trends

This graph is a current representation of the ratio of geriatricians worldwide to a population of 10,000 people aged 65 year and older (Figure 1). The number of geriatric physicians is expected to be halved by 2030 due to the slow growth of their field in addition to the rapid aging of the world population. As a result, specialized health professionals will have to start learning about providing geriatric care to older patients to maintain a good quality of life for their demographic.

References

- Kuldeep D, Patel SK, Kumar R, Rana J, Yatoo MI, et al. (2020) Geriatric population during the covid-19 pandemic: problems, considerations, exigencies, and beyond. Front in Public Health 8: 574198.

- Kai L, Chen Y, Lin R, Han K (2020) Clinical features of COVID-19 in elderly patients: A comparison with young and middle-aged patients. J infect 80(6): e14-e18.

- Ying L, Gayle AA, Smith AW, Rocklöv J (2020) The reproductive number of COVID-19 is higher compared to SARS coronavirus. J Travel Med 27(2): taaa021.

- Berner YN (2012) The challenge of geriatric medicine in the twenty-first century. Harefuah 151(9): 518-519.

- Miller KE, Zylstra RG, Standridge JB (2000) The geriatric patient: A systematic approach to maintaining health. Am Fam Physician 61(4): 1089-1104.

- Besdine R, Boult C, Brangman S, Coleman EA, Fried LP, et al. (2005) Caring for older Americans: The future of geriatric medicine. J Am Geriatr Soc 53(6 Suppl): S245-S256.

- Mangoni AA (2014) Geriatric medicine in an aging society: Up for a challenge? Front Med 1: 10.

- Anthony JNRB (2020) Use of telemedicine and virtual care for remote treatment in response to Covid-19 pandemic. J Med Syst 44(7): 132.

- Board on Health Care Services: Institute of medicine (2012) The role of telehealth in an evolving health care environment: Workshop summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US), USA.

- Morley JE (2004) A brief history of geriatrics. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 59(11): 1132-1152.

- Evans JG (1997) Geriatric medicine: A brief history. BMJ 315(7115): 1075-1077.

- Lynda AA, Goodman RA, Holtzman D, Posner SF, Northridge ME (2012) Aging in the United States: Opportunities and challenges for public health. Am J Public Health 102(3): 393-395.

- Ellis G, Sevdalis N (2019) Understanding and improving multidisciplinary team working in geriatric medicine. Age and Ageing 48(4): 498-505.

- Goodwin JS (1999) Geriatrics and the limits of modern medicine. N Engl J Med 40(16): 1283-1285.

- Robert KL (2002) The future history of geriatrics: Geriatrics at the crossroads. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A 57(12): M803-M805.

- Morley JE (2021) Editorial: Telehealth and geriatrics. J of Nutr Health Aging 25(6): 712-713.

- Ronald MC (2015) Geriatric telemedicine: Background and evidence for telemedicine as a way to address the challenges of Geriatrics. Healthcare informatics research 21(4): 223-229.

- Esterle L, Fritz AM (2013) Teleconsultation in geriatrics: Impact on professional practice. Int J med inform 82(8): 684-695.

- Gillespie SM, Shah MN, Wasserman EB, Wood NE, Wang H, et al. (2016) reducing emergency department utilization through engagement in telemedicine by senior living communities. Telemedicine J E Health 22(6): (2016): 489-496.

- Gajarawala SN, Pelkowski JN (2021) Telehealth benefits and barriers. J Nurse Pract 17(2): 218-221.

- Kruse CS, Frederick B, Jacobson T, Monticone DK (2017) Cybersecurity in healthcare: A systematic review of modern threats and trends. Technol Health Care 25(1): 1-10.

- Ponemon Institute & IBM Security (2018) Cost of data breach study.

- Zhou L, Thieret R, Watzlaf V, Dealmeida D, Parmanto B (2019) A telehealth Privacy and security self-assessment questionnaire for telehealth providers: Development and validation. Int J Telerehabil 11(1): 3-14.

- Seuren, LM , Wherton J, Greenhalgh T, Cameron D, Christine AC, et al. (2020) Physical examinations via video for patients With Heart Failure: Qualitative Study Using Conversation Analysis. J Med Internet Res 22(2): e16694.

- Fairchild LS, Elfrink V, Deickman A (2008) Chapter 48 patient safety, Telenursing, and Telehealth. In: Hughes RG, patient safety and quality: An evidence-based handbook for nurses. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, USA.

- Vaportzis E, Clausen MG, Gow AJ (2017) Older adults perceptions of technology and barriers to interacting with tablet computers: A focus group study. Front Psychol 8: 1687.

- Chu A, Smith BM (2010) The outcomes of anxiety, confidence, and self-efficacy with Internet health information retrieval in older adults: a pilot study. Comput Inform Nurs 28(4): 222-228.

- Chan MY, Haber S, Drew LM, Park DC (2016) Training older adults to use tablet computers: does it enhance cognitive function? Gerontologist 56(3): 475-484.

- Carlo C, Pozzani G, Pozzi G (2016) Telemedicine for developing countries. A survey and some design issues. Appl clin inform 7(4): 1025-1050.

- (2020) 65 and older population grows rapidly as baby boomers age. United States Census Bureau, USA.

- Morley JE (2019) The future of geriatrics. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging 24(1): 1-2.

© 2022 Yashwant Pathak. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)