- Submissions

Full Text

Novel Research in Sciences

Sexual Knowledge, Self-Esteem, and Impulsivity Among Sexual Offenders

Brittanee Miller*, Stephen EB and Gilly Koritzky

Department of Chicago School of Professional Psychology, USA

*Corresponding author: Brittanee Miller, Department of the Chicago School of Professional Psychology, USA

Submission: July 18, 2022;Published: July 29, 2022

.jpg)

Volume11 Issue4July , 2022

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine if there are significant differences in the level of impulsivity, sexual knowledge, and self-esteem between sex offenders with differing sex offenses. The participants were selected based on their participation in outpatient sex offender treatment in a southern California program. Data including general demographics, types of sexual offenses, levels of self-esteem using the RSES, impulsivity using the BIS-11, and sexual knowledge using the MFSKQ, from 44 participants was gathered and analyzed to investigate factors that contribute to sexual offending. Confidentiality was of the upmost importance given the sensitive nature of the participants and the study. It was found that convicted sex-offenders scored lower on sex-knowledge than the normative group. It was also found that the sex-offender participants scored lower in impulsiveness than maximum security felons, but also lower than norms for college males. Clearly, the relationship of difficulties with impulsiveness and commission of sex-crimes specifically, is complex and not intuitively obvious.

Introduction

It is estimated that every 73 seconds an American is sexually assaulted (RAINN. 2012). Sexual violence (SV), or sexual assault, refers to a variety of criminal acts from sexual threats to unwanted contact, to rape. Sexual violence is a serious problem for public health and safety that affects the health and well-being of individuals all over the world. These crimes have received considerable attention in recent media as well as from policymakers, large businesses and corporations, and the public. Appropriately, a substantial amount of research projects, publications, and training curricula related to sexual assault and management of sexual offenders has been conducted [1-4]. Etiology of sexual offending is multifaceted and complex, which makes prevention and treatment a challenge. Those who are perpetrators of sexual crimes come from different genders, ethnicities, and socioeconomic classes [2] which makes it difficult to isolate just a single factor that contributes to their behavior. Due to the multifactor risks associated with sexual offenders, professionals may have a difficult time identifying what areas to target for treatment, particularly if not all risk factors have been identified. Consequently, there is a consistent rise in reported sexual offenses with the public seeking more and more answers on how to prevent sexual assaults from occurring. Prevention starts with first identifying all the prevalent risks. It is difficult to estimate the exact number of sexual assaults that happen per year due to underreporting of sexual assaults [4-7]. This underreporting occurs for several reasons including the stigma and insensitive treatment often associated with these crimes and the difficultly in conceptually measuring what sexual violence is [8]. In addition to psychological costs, sexual crimes have financial costs also. In 2015, rape was estimated to cost the United States approximately $127 billion dollars, which is more than any other crime in the United States.

The majority of sexual offenders are White/Caucasian males [2], however there are also a small number of female sexual offenders. For the purposes of this study, the focus will be on male sexual offenders due to the majority of the available research as well as the majority of identified offenders being males. Although being a male is one factor, there are other factors including but not limited to significant social influences, capacity for relationship stability, impulsivity, general social rejection/ loneliness, lack of sexuality knowledge, self-esteem and poor cognitive problem solving, that also appear to be risk factors [9]. These risk factors are typically assessed based on professional judgment and offender’s self-report, which makes identification and assessment of risk factors susceptible to error and biases. In addition, it is not clear whether there are differences among those who commit different types of sex crimes. Thus, being able to differentiate differences among different types of offenders could be helpful in understanding those who commit such offenses. A sexual offence is the legal name given to a set of complex sexual behaviors and attitudes such as pedophilia, rape, and indecent exposure. While these crimes are lumped into one general category, the categorization of these crimes (e.g., child molestation, rape, exhibitionism, etc.) and trying to understand the distinct character traits of what are described as homogenous groups of offenders could be crucial. For example, [10] identified aggression, hostility, and vindictiveness as the motivation for rape, while child molesters tend to be classified under their level of fixation or focus on children and sexual thoughts about children [11]. Although these classifications tell us very little about the individual offenders, these groups are necessary to help make decisions about treatment and interventions.

One area with limited research regarding the sex offender population is the relationship between aggression and self-esteem. Available research demonstrates some correlation between lower self-esteem among child molesters compared to rapists, and child molesters report lower levels of aggression, anger, and hostility compared to rapist and nonsexual violent offenders [12]. Early researchers believed that low levels of self-esteem were directly related to aggression. However, it was later suggested that high selfesteem was related to aggression [4,13,14]. This confusion between low self-esteem and high self-esteem being directly related to aggression is also found within other forensic populations [15]. For example, it has been suggested that low-self-esteem is a cause of aggression in prison settings due to poor emotional regulation [16]. Recent theories have suggested impulsivity as a key factor in the explanation of sexual offending. For example, Fernandez and colleagues [9] note that the basic concept behind impulsive acts is concerned with identifying behaviors across several settings in which the individuals engage in irresponsible decisions with a lack of long-term goals. According to one theory, lifestyle impulsivity is one of the most established correlates of criminal behavior [17]. Individuals who exhibit what is generally considered a “character trait” of impulsivity problems typically exhibit these features at a young age [9]. Impulsivity has been shown to predict recidivism among sexual offenders [18,19].

Poor cognitive problem solving is associated with impulsivity and has also been shown to be a risk factors associated with sexual offending [9]. Individuals who struggle with identifying and solving everyday problems may fail to take the perspective of others and fail to recognize how their own behaviors are influencing their experiences. This is consistent with Mann, Hanson, and Thornton’s research that found a high correlation between poor problem solving and sexual recidivism [20]. One problematic area of poor cognitive functioning for sexual offenders appears to be lack of sexual knowledge [20]. Sexual knowledge provides individuals with a good foundation to understand sexual development, thus influencing their physical and emotional understanding of sexual relationships. Despite that perspective, there is no clear evidence to support the theory of there being associations between sexual knowledge and sexual offending among boys and men. Some research and some have found that there is no relationship between sex education and sexual behavior [21]. Somers and Gleason [22], for example, found that sexual education that was obtained from family members was related to increased sexual behaviors and “more liberal attitudes among high school students (pg. 674).” Other research has found that sex and STD education programs have produced participants with increased knowledge [21]. However, there are few programs that change actual sexual risk-taking behaviors. One study was among the first attempts at determining the role that sexuality education plays in sexual behavior [23]. They did not find a significant difference between those who received sexual education and those who did not as to who engages in sexual intercourse. However, there was a significant finding of greater use of contraceptives among women who participated in the program [23].

In another early study, surveys were administered to junior high schools and high schoolers who received sexuality education based on their state’s curriculum and a control group [24]. It was found that students who participated in the sex education program postponed their first sexual intercourse experience and showed an increase in contraceptive use consistent with Zelnik and Kim [23]. Interestingly, Zabin and colleagues also found changes in knowledge and behavior were significantly more evident among younger students (junior high) than older students (high school) [24]. This illustrates the need to explore prevention programs for sexual education and their relationship to emotional and physical sexual behaviors since evidence on the theorized relationship of sexual knowledge and sexual offending is lacking.

Statement of the problem

There are multiple theories suggested for why people sexually offend. Some of these theories include single-factor theories such as abnormalities in the structure of the brain and varying hormone levels and others include multifactor theories such as Stinson, Sales, and Becker’s Multimodal Self-Regulation Theory. Sexual offenders are classified by the types of offenses they have carried out and common characteristics or traits. Each classification has a different implication for therapeutic management. Of particular concern is the well-established role that impulsivity plays in criminal behavior. Gottfredson and Hirschi noted that lifestyle impulsivity is one of the most established correlates of criminal behavior [17]. However, there is little to no research specifically on the relationships of sexual knowledge and impulsivity on sexual offending behavior. In addition, establishing the role that self-esteem may play in the actions of sexual offenders as well as the possible differential association with different types of sexual offenses would also be valuable in understanding and treating sexual offenders. Treatment of offenders takes place after the sexual assault has already occurred. Victims of such crimes are subjected to ongoing therapy and significant economic stress. A number of factors have been found or proposed to be related to sexual offending including: community/societal factors, family environment and history, family characteristics, family relationships, peer attitudes and behaviors, hypermasculine/all-male peer groups , association with antisocial peers, intimate partner processes and characteristics, partner relationship conflict, sexual behaviors and other noncognitive sex-related factors , psychosocial factors, sex-related cognitions, interpersonal skill factors, gender-based cognitions, violencerelated cognitions, and substance use. Of the identified factors, sexuality education appears to be excluded from the majority of the research. Thus, the relationship between sexual knowledge and sexual offending has not been established has not been established. Therefore, there is insufficient research examining the relevance of providing sexuality education and dealing with impulsivity as part of a primary prevention technique.

The current study is a quantitative design examining sexual knowledge, self-esteem, and impulsivity among adult male sexual offenders. The study gathered data from questionnaires distributed to voluntary participants who are registered sex offenders in the state of California. The sample was derived from adult males who participate in sex offender treatment with Open Door Counseling. Participants will be categorized based on the type of offense they committed. By analyzing the association among sexual knowledge, impulsivity, self-esteem, and sexual offending this study aims to identify contributing factors to sexual offending and differential relationships with different types of offenses. By addressing the relationships among sexual knowledge, self-esteem and impulsivity and their influence on sexually violent behaviors, this study aims to help reduce the number of sexual assaults per year by helping create better prevention programs and tailored treatment programs. Given the alarming number of sexual assaults that are being reported, the need to help decrease the number of sexual assault victims is of great importance to society and to potential victims.

The present study

There are an alarming number of sexual assaults and sexually violent acts that occur each year. Both men and women of all ages, ethnicities, and backgrounds continue to be victimized in the United States. Despite the attitudes toward sexual offending and severe punishment there continues to be thousands of reported offenses each year in the United States. Perpetrators of sexual offending vary in age, gender, ethnicity, personality, and socioeconomic background. The origins or causes of sexually abusive behavior remain unclear. Understanding the etiology of sexual offending allows professionals and experts to develop effective prevention and treatment programs to mitigate the risk of sexual offending. Specifically, examining different classification of sexual offending, and how the characteristics of each typology relate to issues of impulsivity, self-esteem and sexual knowledge will help to establish their hypothesized relationships to sexual offending and better assess risk factors for different individuals. Thus, the purpose of this study was to investigate the relationships among, self-esteem, sexual knowledge, and impulsivity of differing sexual offenders. There are arguments that impulsivity is a major contributor to sexual offenses. Although impulsivity may be a contributing factor in sexually abusive behavior, it is unknown whether knowledge of sexual health can have an impact on impulsive sexual behaviors and what role the offender’s self-esteem plays in the sexual aggression against others. Further, the majority of the research has focused on personality theories and social learning theories. Therefore, there is little known of potential sexual knowledge, self-esteem, and sexual education differences of sexual offenders.

Data was gathered from registered sex offenders in the state of California. Participants were obtained through sex offender treatment programs across southern California. Participants of the study provided voluntary data on sexual education history, current sexual knowledge, impulsivity, self-esteem score and type of sexual offense they committed using a demographic questionnaire, impulsivity scale, self-esteem scale and sexual knowledge questionnaire. The relationships between sexual knowledge and impulsivity of sexual offenders needs to be better understood to identify more specific issues to be addressed in future prevention programs to ultimately eliminate sexually assaultive behavior.

Null hypotheses

The participants were divided into 3 classifications based on

the type of crime they committed: 1) those with victims under

18, 2) those with sexual assault/rape victims, and 3) those with

indecent exposure/voyeurism.

i. There will be no differences among types of offenders in sexual

knowledge.

ii. There will be no differences among types of offenders in selfesteem

scores.

iii. There will be no difference among types of offenders in scores

on impulsivity

iv. There will be no differences between each sex offense category

and norms for non-incarcerated individuals on the BIS.

v. There will be no differences between each sex offense category

and norms for the Sexual Knowledge questionnaire.

Figure 1: Map showing Badagry creek, Lagos lagoon and Ikorodu coastal areas of Lagos State.

Methods

Participants

The aim was to seek completed surveys from 60 convicted sexual offenders, over the age of 18, receiving treatment in the state of California, regardless of where the offense was committed. The participants must have been convicted of a sexual offense. Participants were recruited from a company that provides sexual offending treatment for sex offenders on probation and parole. Written permission was given to post flyers around the building including in the lobby and group rooms at two locations in Southern California. The recruitment flyer directed them to a link to the survey if they are interested in considering participating. There are no restrictions as to ethnicity nor age so long as the participant is at least over the age 18. All participants identified as male. An emphasis was placed on voluntary participation to ensure prospective participants did not feel obligated to complete the survey. Prospective participants will be clearly informed that no personally identifiable information will be collected as part of the study. Were clearly informed of the anonymity and voluntariness of the study.

A total of 44 participants provided fully usable data. When reviewing their self-report of their major sex offense, it was possible to classify them into 1 of 3 categories of Offense. The majority [25] of the participants reported having committed an offense against a minor. Offenses against minors could include rape/assault, inappropriate touching/molestation, and/or pestering or harassing a minor in an aggressive manner. Eleven of the participants reported having been convicted of rape or sexual assault against adults. This could include a stranger, acquaintance, or spouse aged eighteen or older. There were 5 participants whose reported crime did not fit either of those categories, and they were classified as other sex offense.

Based on the participants’ self-report, they were classified into 1 of 4 ethnicity groups. Thus, there were 21 self-classified as white, 14 classified as Hispanic, 5classified as black and 5 classified as Other/Bi-racial. Regarding education, 3 levels or type of education were derived. There were 2 participants who declined to provide their education level. Based on the researcher’s experience with this population, it was determined that if they had a college education or trade school education, that they would have reported that. Therefore, it should be understood that the classification of less than college includes these individuals. The other categories were college or above and a category of trade school education.

Measures

Demographic questionnaire: Data collected from all participants included age, ethnicity/race, type of sexual offense and age at sexual offense. The demographic questionnaire was anonymous and did not collect any personally identifiable information. Participants were also asked about their employment status, marital status, if they attended sexual education classes and in what ways they obtained their sexual knowledge. Additional information that the questionnaire will account for includes, language(s) spoken, current identified religion, and religion identified with during childhood and adolescence.,

Miller-Fisk sexual knowledge questionnaire:

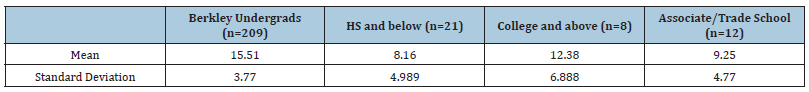

a. Sexual knowledge: is defined as comprehension of general human sexual development, contraceptive methods, male and female reproductive anatomy, and sexually transmitted diseases as measured by the 24-item version of the Miller-Fisk sexual knowledge questionnaire. The instrument was designed for use in educational settings and as a screening device to measure knowledge of a range of sexuality issues with adolescents. The 24- Item Version of the Miller-Fisk Sexual Knowledge Questionnaire (SKQ was designed for use in studies of sexual behavior [25]. It measures knowledge related to reproductive physiology, contraceptive approaches, and issues related to fertility and infertility. Respondents choose among four-option multiple-choice selections or true/false items. A total score encompasses the number of correct responses. A higher number of correct responses suggest more sexual knowledge. Miller and Fisk (Gough developed the original 49-item test of sexual knowledge at the Stanford University School of Medicine in 1969 [25]. Twenty-five items were subsequently dropped by the authors as psychometric analysis suggested they either insignificantly or negatively correlated with the total score. Gough administered the shortened questionnaire to male and female college students (N=355). For each of the 24 items, point-biserial correlations were computed between correct answer to the item and total score. All the point-biserial correlations were significant beyond the .01 level of probability, suggesting an acceptable degree of internal consistency [25]. The corrected split half reliability coefficient for total score was .67, N = 355. Mean scores for females were significantly higher (p < .01) than males (females, 16.55, SD = 3.69; males, 15.51, SD = 3.77). The Kuder-Richardson formula 20 (K-R20) reliability coefficient for this current sample was .4612.

b. The barratt impulsiveness scale-11: The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, Version 11 (BIS-11 [26]. Itis a 30 item selfreport questionnaire designed to assess general impulsiveness considering the multi-factorial nature of the construct. The structure of the instrument allows for the assessment of six firstorder factors (attention, motor, self-control, cognitive complexity, perseverance, cognitive instability) and three second-order factors (attentional impulsiveness [attention and cognitive instability], motor impulsiveness [motor and perseverance], non-planning impulsiveness [self-control and cognitive complexity]). A total score is obtained by summing the first or second-order factors. The items are scored on a four-point scale (Rarely/Never [1], Occasionally [2], Often [3], Almost Always/Always [4]).

c. The Rosenburg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE): The RSE is a 10-item measurement that asks respondents how strongly they agree or disagree with statements regarding their self-esteem. The RSE reports having an excellent internal consistency with a Guttman scale coefficient of reproducibility of .92. The test-retest reliability over a period of 2 weeks showed correlations of .85 and .88, indicating excellent stability. The RSE also, demonstrates concurrent, predictive and construct validity using known groups. The RSE correlates significantly with other measures of self-esteem, including the Coopersmith Self-Esteem Inventory. In addition, the RSE correlates in the predicted direction with measures of depression and anxiety.

Procedures

Potential participants accessed the study by going to the on-line site specified in the posted recruitment flyer. Upon accessing the site, they were presented with the Informed Consent Form. They indicated their consent by clicking the ‘I Consent” button. They were then presented with the demographic questionnaire form, then the Rosenburg Self-Esteem Scale, then the Barret Impulsivity Scale, and finally the Miller-Fisk Sexual Knowledge Questionnaire form. After completing the last form, they saw the Debriefing Statement that included a follow-up and referrals and researcher’s contact information. All the information gathered is anonymous, with no identifying information obtained. All information that was collected will be kept on a numerical and facial recognition password protected computer. In addition, the data will be kept for five years and then properly destroyed via secured shredding.

Result

Since only 44 individuals contributed usable data for all the variables, the p level that will be used for reporting results will be .10 or less as the biggest concern is to miss possible significant results that therefore would not be pursued in further studies. In the design of this study, there were certain categories of particular variables for which specific comparisons were desired. Consequently, following are reported the results of planned comparisons (LSD) for three categories of data analyses: Sex Offense Category (3 categories), Ethnicity (4 classifications), and Education (3 categories).

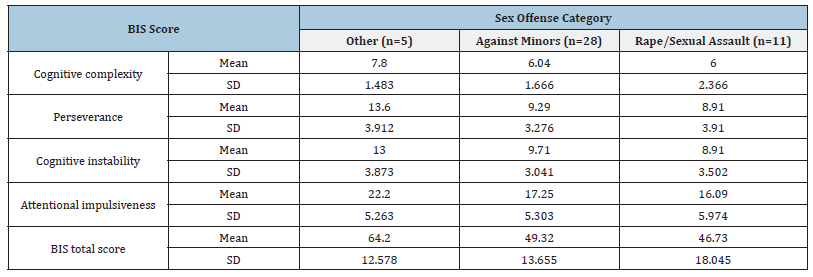

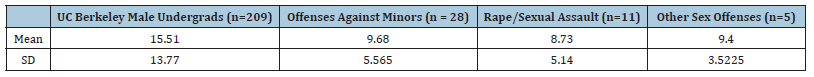

Analyses of sex offense categories

When examining the sex offenses that the participants listed, it was possible to define two specific categories: Acts Against a Minor and Rape/Sexual Assault, and one broad category of Other. Planned comparisons of the three categories across all the dependent measures revealed significant differences in 4 of the BIS categories and for Total BIS score. The means and standard deviations for each of the BIS where differences were revealed are reported in Table 1. It can be seen in Table 1 that the Category Other obtained significantly higher scores than the other two categories of sex offenses on 4 of the BIS sub-scales and on Total BIS score. Thus, on Cognitive Complexity (not enjoying challenging tasks), Other offenses scored higher than Offenses Against Minors (p=.056) and Rape/Sexual Assault Offenses (p=.078). Similarly, Other offenses was higher on Perseverance (not having a consistent lifestyle) score than Against Minors offenders (p=.015) and had a higher score than Rape/Assault offenders (p=.017). Other offenses scored higher on Attentional Impulsiveness both in comparison to offenders Against Minors (p=.070) and Rape/Assault offenders (p=.045). In addition, those who committed other offenses had higher cores on Cognitive Instability than those who committed offenses against minors (p=.025, and those who committed Rape/Sexual Assault (p=.044). Last, Other offenses was higher on Total BIS score compared to those whose offense was Against Minors (p=.044) and those whose offense was Rape/Sexual Assault (p=.034). Thus, those who were classified as other types of sex offenses scored higher in some categories of impulsiveness and in total impulsiveness score than the other two sex offense categories. Therefore, regarding null hypothesis 3, there were differences between the other category and the two specific sex offenses categories, and therefore, null hypothesis two can be rejected regarding the other category. Regarding null hypothesis 1, there were no differences in the sex-knowledge scores between any of the three sex offense categories. Therefore, null hypothesis 1 cannot be rejected. Similarly, there were no differences among the sex-offense categories regarding self-esteem scores, therefore, null hypothesis two cannot be rejected.

Table 1:Means, SDs and n for each category of sex offense committed where there were significant differences on BIS scores.

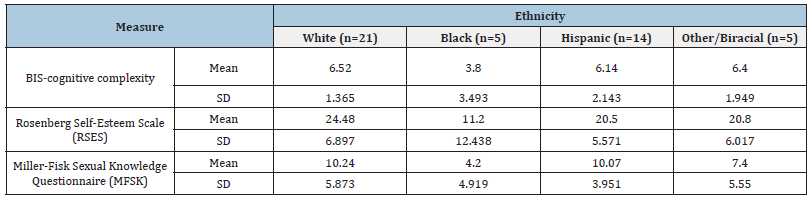

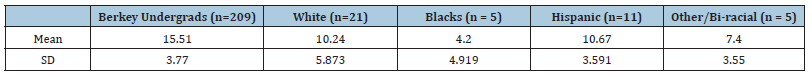

Analyses of ethnicity

When examining the ethnicity of the participants, four categories were delineated. Planned comparisons of the four groups across all the dependent measures revealed significant differences in one of the BIS categories, and in self-esteem scores, and on sexual knowledge scores. The means and standard deviations for each of the specific categories where differences were revealed are reported in Table 2. Those participants who identified as Black scored significantly lower on BIS Cognitive Complexity (not enjoy challenging mental tasks) than White (p=.009), Hispanic (p=.029), and Other/Biracial (p=.044) participants. Regarding Self- Esteem, participants who identified ethnically as Black reported significantly lower self-esteem scores than White (p=.001), Hispanic (p=.017), and Other/Biracial (p=.041) participants. Last, Black participants scored significantly lower on sexual knowledge than White (p=.025), and Hispanic (p=.036), but not lower than Other/Biracial participants (p=37).

Table 2:Means and standard deviations (with n in parentheses) for the 4 ethnicity categories for the significant ethnicity differences on bis cognitive complexity, self-esteem, and sex knowledge.

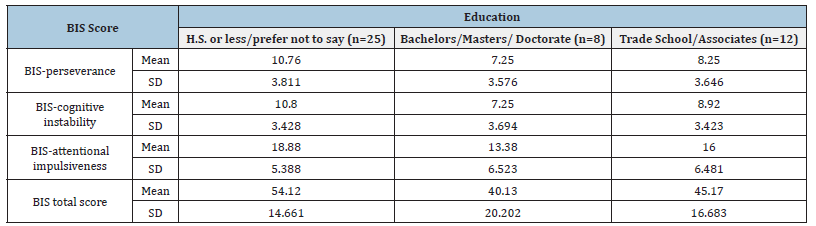

Analyses of education

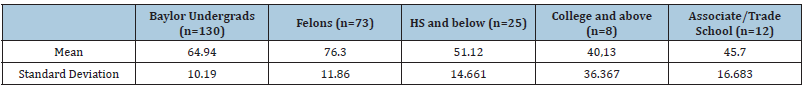

When examining Education levels that the participants listed, 3 specific categories were delineated: High school or less/Prefer not to say; Bachelors, Masters, and Doctorate; and Associates/ Trade school. A total of two participants did not indicate their education level and were grouped with high school or less. Planned comparisons of the three categories across all the dependent measures revealed significant difference on 3 subscales of the BIS and Total BIS score. The means and standard deviations for each of the specific education categories where differences were revealed are reported in Table 3. As seen in Table 3, on Non-Perseverance, High school or less and prefer not to say scored higher (p=.025) than those with a bachelors, masters, and doctorate education as well as compared to Trade School/Associates education (p=.062). Similarly, High School or less and prefer not to say scored higher on Cognitive Instability than those with Bachelors, Masters, and Doctorates (p=.016). High school or less/Prefer not to say scored higher on Attentional Impulsiveness than those with Bachelors, Masters, and Doctorate education (p=.026). Last, education category of High school or less/Prefer not to say scored higher on BIS Total than Bachelors, Masters, and Doctorate (p=.040). Thus, those with lower education levels exhibited higher impulsiveness on several BIS sub-scales and on Total Score.

Table 3:Means and standard deviations (with n in parentheses) for the 3 education categories for the significant education level differences on bis perseverance, cognitive instability, attentional impulsiveness, and total score

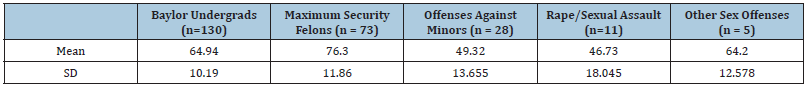

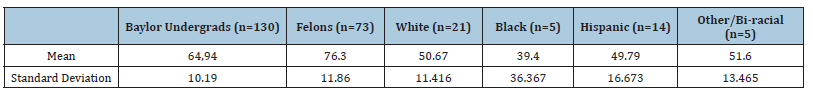

Comparisons with norms for BIS and for sex-knowledge

Null Hypothesis 4 proposed that there would not be any differences in the Total BIS scores obtained by each of the sexoffense categories and the norms available on the sex-knowledge quiz. Patton, Stanford, and Barratt (1995) provided means and standard deviations for male, Baylor University undergrad students as well as means and standard deviations for felons sentenced to a maximum-security prison. The means and standard deviations for these two groups are presented in Table 4 along with the means and standard deviations for each of the three sex-offender groups. In accord with null hypothesis 4, t-tests were computed comparing each of the sex-offender groups with the mean and standard deviation for the male, Baylor University students. Two of those three comparisons produced significant results. As can be seen in Table 4 the male, Baylor students scored higher on BIS Total Impulsiveness score compared to those who committed offenses against minors (t (156)=6.8978, p=.0001, and higher BIS Total Impulsiveness scores than those who committed rape or sexual assault offenses (t(139)=5.366, p=.0001), but not compared to those who committed other sexual offenses (t (133)=.1581, p=.8746). Thus, Null Hypothesis 4 can be rejected regarding those who committed offenses against minors and regarding those who committed Rape/Sexual Assaults.

Table 4:Means and standard deviations (n in parentheses) for three types of sex offenders and Baylor university male undergrads and maximum-security male felons on total BIS scores.

However, when the three sex-offense categories were each compared to the maximum-security felons, all three scored lower in Total BIS Impulsiveness score. Thus, the felons scored higher than those who committed offenses against minors (t (99)=9.8076, p=.0001), and higher BIS Total Impulsiveness score than those who committed rape or sexual assault offenses (t (82) =7.1563, p=.0001), and higher than those who committed other sexual offenses (t (76)=2,1998, p=03). Null Hypothesis 5 proposed that the three sex-offense categories would not differ from the available norm for the sex-knowledge scale. Gough (1974) provided norms for male, undergraduate UC Berkeley students. The means and standard deviations for the three sex offense categories and for the male, Berkeley undergrad students in 1974 are provided in Table 5. All three of the t-test comparisons of the norms for the UC Berkeley male undergrads with each of the sex offender categories were significantly different for sex-knowledge scores. Thus, the Berkley males scored higher in sex-knowledge than those who committed offenses against minors (t (235)=7.2114, p=.0001), and higher than those who committed rape/sexual assault crimes (t (218)=5.7024, p=.0001), and higher than those who committed other sexual offenses (t (212)=3.5857, p=.0004). Thus, Null Hypothesis 5 can be rejected. Additional paired comparisons were conducted comparing each ethnic group with the Berkley male undergraduates on sex-knowledge scores. The means and standard deviations are reported in Table 6.

Table 5:Means and standard deviations (n in parentheses) for three types of sex offenders and UC Berkeley male undergrads on sex-knowledge scores.

Table 6:Means and standard deviations (n in parentheses) for four ethnic groups and Berkeley university male undergrads for sex-knowledge scores.

Every t-test comparison was significant at the .0001 level. As can be seen in Table 6, the Berkley male undergraduates obtained higher sex-knowledge scores the white sex offenders (7(228)=5.7568, than the black sex offenders (t (212)=6.5659), higher than the Hispanic offender (t (218)=(4.159) and higher than the other/biracial group (T (212)=4/7588. If the Berkley norms can be taken as a “standard,” then each of the ethnic categories for the sex offenders could be deficient in their sexual knowledge. Additional paired comparisons were conducted comparing the total impulsiveness scores of each of the ethnic classifications with the male, Baylor U undergrads, and separately with the Maximum-Security felons on BIS Total scores. The means and standard deviations are presented in Table 7. Regarding the t-test comparisons of each ethnic category with the maximum-security felons, every comparison was significant at the .0001 level. Thus, it can be seen in Table 8 that the felons scored higher in impulsiveness than the white ethnic group (t (92)=8.7977), higher than the black ethnic group (t (76)=5.6043, higher than the Hispanic ethnic group (t (85)=7.1481, and higher than the Other/Bi-racial ethnic group (t (76)=4.4713. These results indicate that the felons scored as more impulsive than every one of the ethnic classifications.

Table 7:Means and standard deviations (n in parentheses) for four ethnic groups and Berkeley university male undergrads and maximum-security male felons on total bis scores.

Regarding the t-test comparisons of each ethnic category with the male, Baylor U undergrads, three of the comparison were significant at the .0001 level, whereas the comparison with the ethnic category of other/bi-racial was significant at the .0052 level. Thus, it can be seen in Table 8 that the Baylor males scored higher in impulsiveness than the white ethnic group (t (149)=5.8049),higher than the black ethnic group (t (133)=4.7281, higher than the Hispanic ethnic group (t 142)= 4,9213, and higher than the Other/ Bi-racial ethnic group (t133=2.8409). These results indicate that the male, Baylor undergrads scored as more impulsive than every one of the ethnic classifications. Additional paired comparisons were conducted comparing the scores of each of the 2 education classifications with the male, Baylor undergrads, and separately with the Maximum-Security felons on BIS Total scores. Means and standard deviations are presented in Table 8. Regarding the t-test comparisons of each education category with the maximumsecurity felons, every comparison was significant at the .0001 level. Thus, it can be seen in Table 9 that the felons scored higher in total impulsiveness score than the high school or less group (t (98)=9.3425), higher than the college and above education group (t (79)=7.6436, and higher than those with associate or trade school education group (t (83)=8.2408)., These results indicate that the felons scores as more impulsive than every one of the education classifications. Regarding the t-test comparisons of each education category with the male, Baylor U undergrads, every comparison was significant at the .0001 level. Thus, it can be seen in Table 9 that the felons scored higher in total impulsiveness score than the high school or less group (t (155)=2.2428), higher than the college and above education group (t (136)=6.2206, and higher than those with associate or trade school education group (t (140)=5.8472)., These results indicate that the college students scored as more impulsive than every one of the education classifications. Additional paired comparisons were conducted comparing the sex-knowledge scores of each of the education classifications with the male, Berkley U undergrads. The means and standard deviations are presented in Table 9.

Table 8:Means and standard deviations (n in parentheses) for 3 education classification groups and Baylor university male undergrads and maximum-security male felons on total BIS scores.

Table 9:Means and standard deviations (n in parentheses) for three educational groups and Berkeley university male undergrads on sex-knowledge scores.

Regarding the t-test comparisons of each education category with the male Berkeley undergrads, every comparison was significant the .0001 level. Thus, it can be seen in Table 8 that the Berkley males scored higher in sex-knowledge than the high school or less group (t (232)=11.208, p=.0001), higher than the college and above education group (t (215)=2.221, p=.0274), and higher than those with associate or trade school education (t (218)=85.5112)., These results indicate that the college students scored higher in sex-knowledge than every one of the education classifications.

Discussion

Sexual violence is a serious problem for public health and safety. A considerable amount of attention in recent media has been given to the discussion of sexual assaults and other sexually violent crimes, which have gone under reported for years. The perpetrators of these sexually violent offenses vary in age, sex, education history, socioeconomic status. The etiology of sexual offending remains complex, and researchers have used multiple theories to suggest why people sexual offend [9,10]. However, there is little to no research investigating personal factors, such as sexual knowledge and education, and personality characteristics such as impulsivity and self-esteem. Therefore, this study was designed to study the relationships among impulsivity, sexual knowledge, selfesteem, and types of sexual offenses. Significant relationships were found between sex offense categories, ethnicity, and education level and various of the impulsivity, self-esteem, and sex-knowledge scores. Regarding the measures of impulsivity, self-esteem and sex-knowledge, the findings are discussed first regarding each of the following three categorizations of the participants: first for sex offense categories, then for ethnicity and then for education level. Then, the scores for those categorizations of the sex-offenders were compared to the limited, available “norms” for the impulsivity and sex-knowledge measures. Significant differences were found for the sex-offender participants and “norms” for college students and maximum-security felons.

Sexual offense categories

Due to the limited responses received, it was necessary to create two specific categories of sexual offense and one broad category: Acts Against Minors, Rape/Sexual Assault, and a broad category of Other sexual offense. The offenses of the five participants whose sex offenses that fall under the category of Other include: sexual exploitation, transmission of harmful material online, kidnapping, and attempted kidnapping. The data revealed that the participants in the category Other had significant correlations to impulsivity worth discussing and exploring further. In this study, analysis of sexual offender typologies revealed significant findings for the broad, other category related to impulsivity in that this group of offenders had higher impulsivity scores than the other two categories of sex-offenders. The categories used in this study broadly match the literature that impulsivity is linked to sexual aggression [27]. High impulsivity has been linked to greater risk of recidivism; however, research has shown that individuals with internet crimes have low recidivism risk [28,29]. The findings here are inconsistent with findings from Ryan, Huss, and Scalora, who suggest rapists tend to have higher scores on impulsivity than child molesters and mixed offenders [30]. It may be that this sample of individuals was not representative of the general sexual offender population as it was not those who had been convicted of rape and/ or sexual assault who had the highest impulsivity scores. Certainly, the measure of impulsivity used could make a difference as well as the uniqueness of the 5 participants who were in the other category.

There were no significant correlations between the sexual offender typologies and self-esteem. This is consistent with the mixed research that has explored the relationships between selfesteem and aggression and violence [15]. Research has suggested that inflated self-esteem in conjunction with a distorted sense of self is linked to violence [31]. Conversely, research has also shown that violent offenders have significantly lower self-esteem than the general population [15,31]. Therefore, the exact relationship between sex offenses, sexual offenders and self-esteem scores appears to be complex and unestablished. There were no significant findings between sexual offender typologies and sexual knowledge. Sexual offender typologies were not a good predictor of level of sexual knowledge. However, as will be discussed later, the sexual offenders in this study were shown to score lower on sexual knowledge than the available norms. Also, to be discussed later, education level of the sexual offenders was found to be related to their sex-knowledge scores, which were lower than available norms. As will be discussed later, these results, taken together, suggest that sexual offenders are indeed deficient in their sexual knowledge, even at higher educational levels.

Ethnicity

According to the US Department of Justice, 57% of perpetrators of sexual offenses are White/Caucasian men [19]. Recent national data reveals that of the over 450,000 public registered sex offenders, 72% were listed as White, while 26.5% were listed as Black. The current study observed data from a total of twenty-one white men, five black men, fourteen Hispanic men, and five other/biracial men. It was found that the 5 Black participants showed significant differences from the other ethnicities on the BIS-Cognitive Complexity subscale, the RSES and the MFSK. First, examining the term cognitive complexity, as it relates to the BIS-11, it should be noted that high scores on this scale reflect low endorsement of cognitive complexity. The term cognitive complexity on this measure refers to enjoying challenging mental tasks. As it relates to other research, cognitive complexity has been defined as a multi-dimensional way of thinking that allows for individuals to better process different contexts and differences in individuals [32-34]. In this current study, participants who identified as Black scored significantly lower on the subscale of Cognitive Complexity, translating to a higher endorsement of saying they like and enjoy a mental task than other participants. One possible reason for this finding is that, in theory, individuals from an ethnic minority group should experience higher rates of cognitive complexity given their likelihood to have to navigate complex social constructs such as racism, discrimination and prejudice and interpersonal issues [35]. It could be that the participants in this study are forced in life to adapt to the changes of being a sex offender and navigating under the radar of others for fear of further persecution, discrimination, and prejudice beyond that which comes with their ethnicity. As a result, they need to be oriented to engaging in complex mental tasks that may serve as a survival mechanism as they have a sense that life (for them at least) is a complex puzzle-as reflected in one of the cognitive complexity items.

Consequently, Black individuals who are led to modify their lives due to their sexual offender status may end up feeling lonelier and more depressed. This study found that Black participants scored lower on overall self-esteem than White, Hispanic, and Other/ Biracial participants. It is recognized that the internalization of stigma resulting from the views of others results in low self-esteem. The participants of this study are a part of an extremely stigmatized and disadvantaged group. which is further problematic because of the nature of their offenses. Couple these factors with race and ethnicity, may result in Black participants views of themselves being further negatively reinforced as reflected in this study in their lower scores on the self-esteem measure. The research on sexual knowledge for this particular population has been scarce. Regarding sexual knowledge and sexual literacy, some research suggests that different race-ethnic groups are concerned about different aspects of reproductive health. Black/African Americans tend to be more concerned with side effects of contraceptives, which may be a result of a history of discrimination and general suspicion about medical doctors and the like [36,37], and thus these participants have incorporated a lesser extent of sex-knowledge than the other ethnic groups. It may also be as simple as these 5 participants generally having lower retainment/benefit of their education. The sample size in this study does not permit further examination of combinations of ethnicity and educational level and relationship with sex-knowledge scores.

Education

Education beyond high school requires a certain level of focus, goal-oriented behavior, and impulse control. The relationship between impulsivity and education was not what this study had originally set out to examine, however statistically significant results demand more attention be paid to this relationship that emerged. Among the three categories for education, individuals with High School or less/Prefer not to say unsurprisingly demonstrated high rates of impulsivity on three subscales and overall impulsivity. Several studies have examined the relationship between academic success and impulsivity in children generally finding that children with increased behavioral problems of inattention, hyperactivity,and impulsivity had lower academic success [38]. However very little research appears to examine the relationships for adult age individuals and impulsivity and intelligence [38]. Further, possible relationships between educational level, impulsivity, and sex-offense categories have not been investigated, but the results obtained here suggest that this might be a fruitful avenue of investigation. The pursuit of higher education requires a level of consistency, discipline, and delayed gratification. Participants of this study scored higher on non-perseverance (having a non-consistent lifestyle), cognitive instability, and attentional impulsiveness. The ability to focus on tasks, such as sitting through lecture, reading articles or other assigned readings is essential for education beyond high school. Therefore, the results obtained here that the 8 participants with college or higher education had lower impulsivity scores are consistent with extensive research suggesting that the ability to delay gratification and approach tasks thoughtfully are associated with higher academic success but are not a guarantee that one won’t commit (sexual) offenses [38].

Comparisons with norms for impulsivity and sexual knowledge

Sex-offense categories and norms for impulsivity: This study also wanted to examine and compare the relationship between sex offense categories and the (general population) norms for the BIS- 11 and Sexual Knowledge. Comparisons of the impulsivity scores for each of the sex offense categories with the norms available for the Baylor University undergraduate men found that two of the sex offender groups obtained higher total impulsivity scores than did the Baylor U males, but there was no difference with the other category. It is not immediately intuitive that college males would score as more impulsive than males convicted of sex-offenses against minor, rape, and assault, it might be that it is accurate that college men are quite impulsive, but their impulsiveness does not result in sexual offenses, although date rape on college campuses is real and possibly multiple factors operate regarding possible conviction and incarceration for this segment of the population. Once again, those whose offenses were categorized as Other may be unique in several ways. Regarding comparisons of impulsiveness scores with the maximum-security felons, the felons scored higher in total impulsivity scores than did all three of the sex offender categories. These findings make intuitive sense and are consistent with an expectation that impulsiveness would be a bigger problem for people who commit offenses that get them placed in maximum security, lending a degree of external validity to the findings obtained here.

Regarding sex-knowledge, all the sex-offender categories had lower sex-knowledge scores than the available “norms” for the UC Berkeley male, undergraduates. It should be noted that this “norm” dates from 1974. However, these findings that sexoffenders (males) appear to have less sexual knowledge than other males are consistent with expectations and makes intuitive sense [39]. Regarding maximum security felons there may be some environmental factors associated with impulsivity and being in a locked facility. Some of these factors may include prison culture and being less sensitive to punishment and being especially dangerous. Being less sensitive to punishment may increase acting impulsiveness. In contrast, individuals in this study who are all on parole or probation and risk the chance of returning to prison for any violation of their conditions, being impulsive would be particularly problematic.

Sex-knowledge and sex-offense category: Looking at sexual offenses and sexual knowledge scores compared to the norms of those UC Berkeley undergrads revealed that the undergrads scored significantly higher than all categories of offenses. These results are intuitively obvious and are consistent with the perspective that sex-offenders are deficient in their sexual knowledge. The exact relationship of their deficiency in sexual knowledge and committing sex offenses is a ripe area for future research.

Ethnicity and comparison with impulsivity and sexknowledge norms: Here the findings are quite simple and direct. It did not matter what ethnicity group the participants were classified into. All classifications scored lower in sex-knowledge than the norms available for the UC Berkeley males. Similarly, all 4 ethnic classifications scored lower in impulsivity than the Maximum-Security felons. These findings make intuitive sense and lend an element of external validity to the findings. In contrast, all 4 ethnic categories scored lowed in Total BIS scores than the Baylor University males. As indicated above, it is unclear what factors are at play in the impulsivity scores of college males such that they score higher than convicted sex-offenders, although these college males do score lower than maximum security felons.

Education levels compared to available norms:It was found that all education levels scored lower in sex-knowledge than the scores for the Berkeley males. That finding is not surprising and is consistent with the general conceptualization of sex-offenders. However, it is maybe a bit surprising that even those sex-offender who have college or higher education score lower in sex-knowledge than the UC Berkeley males. It appears that even in obtaining “higher” education, these men wind up missing significant sex knowledge.

Clinical implications:Preventing recidivism for sexual offenders is the main goal of treatment. Currently sex offender treatment in California uses a victim-centered approach. Based on findings from this study, treatment should focus on targeting impulsivity as a specific issue. Methods such as Cognitive-Behavior Therapy (CBT), Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT) and relapse prevention may be beneficial. It is the responsibility of the offender to avoid high risk situations and with the inclusion of these treatment approaches reoffending rates could be reduced because these approaches are likely to put emphasis of responsibility, resisting impulsive behavior and providing techniques to doing so. There were deficits of sexual knowledge among all categories of offenders, so for future clinical implications, a more comprehensive sexual education program should be implemented in schools and in treatment programs. Based on the results obtained here clinicians should not assume that higher formal education attained is not necessarily accompanied with adequate and appropriate sexeducation.

Organizations such as SIECUS fight for the advances of sex education through advocacy and policy. By enhancing educators and provided age-appropriate/developmentally appropriate sex education will arm individuals with the knowledge and foundation for long term positive sexual health outcomes, including less sexual violence and aggression. Treatment providers, as well as educators in all grade levels, should build upon information provided by individuals as they grow into personhood with changing wants, needs, and desires. Individuals treating sex offenders at all age levels should advocate for open discussion about issues related to sexuality and look for ways for individuals to develop a prosocial (non-criminal way to get their sexual needs met. Treatment providers who treat individuals who have committed a sexual offense are unique in that they must utilize empathy and compassion for a population that many people hold in the lowest regard. It is essential for treatment providers to have a level of selfawareness about their own attitudes and beliefs about sexuality. As result, treatment providers may experience burnout/fatigue and self-doubt and may even grow emotionally jaded. Providers should engage in frequent supervision and therapy, when available and needed to address any shifts in attitudes and beliefs as well as burnout concerns

Limitations and directions for future research:Although efforts were made to control for internal and external validity, there are several limitations to this study. The three measures used were self-report measures. Self-report measures pose a reliability risk and can be even more problematic for forensic populations due to positive impression management or fear of repercussion. Measures with reported reliability and validity were used where appropriate but a more current measure of sexual knowledge that are more current can incorporate more components of sexual health and knowledge would be beneficial to obtain a more valid measure of sexual knowledge. Additionally, the content of the questions is personal and may trigger some unwanted or uncomfortable memories and/or thoughts and possibly result in less than fully accurate reports. Research in which empathic relationships with the participants might be helpful in that regard. Thus, intensive interviews (Interpretive Phenomenological Analyses) might help deal with that problem rather than impersonal studies of filling out scales. Despite confidentiality of responses being clearly stressed in the informed consent, participants may not have been completely forthcoming.

Participants were obtained from two southern California sites. A more diverse geographical population would improve the generalizability of this study with this special population. Clearly the sample size was small, especially regarding several of the important classifications used in this study. The fact that significant differences could be obtained with such small samples suggests that there are very powerful effects regarding sex offenses committed and impulsivity, as well as the relationship of education with impulsivity in addition to possible ethnic differences in this forensic population. Therefore, future research will want to obtain larger samples to validate the findings suggested by these results. Additionally, future research may want to look at the differences within the offense categories of sexual offenses against minors.

Summary and conclusion

The purpose of this study was to examine if there was a significant difference in the level of impulsivity, sexual knowledge and self-esteem between sex offenders who committed different types of sex offenses. The participants were selected based on their participation in outpatient sex offender treatment in a southern California program. Data including general demographics, types of sexual offenses, levels of self-esteem using the RSES, impulsivity using the BIS-11, and sexual knowledge using the MFSKQ, from 44 participants. It was found that the relationships among type of sex offense committed, educational level, ethnic identity and impulsiveness, self-esteem and sex-knowledge are somewhat intuitive, but are complex when examined in depth. Based on the results of this research study, there is a great need for sexual literacy among sexual offenders. All the participants of this study were 18 years or older and still struggled with basic sexual knowledge, even those with college and beyond education. The findings from this study also highlighted the need to focus on impulsivity among this predominately male population. As reported above, impulsivity has been associated with lower academic success and possible higher risk for sexual offending, thus it would serve the community to address these concerns as early in development as possible. Implementing better sexual education across the nation and addressing with empathy and compassion the concerns of individuals who struggle with appropriate sexual behavior that is not harmful to others should be paramount.

References

- Hamilton JA (2020) Exploring the relationships between personality disorder, sexual preoccupation, and adverse childhood experiences among individuals who have previously sexually offended (Doctoral dissertation, Nottingham Trent University).

- Ackerman AR, Sacks M (2018) Disproportionate minority presence on us sex offender registries. justice policy journal 16(2): 1-20.

- Ó Ciardha C, Ward T (2013) Theories of cognitive distortions in sexual offending: What the current research tells us. Trauma Violence Abuse 14(1): 5-21.

- Kirkpatrick LA, Waugh CE, Valencia A, Webster GD (2002) The functional domain specificity of self-esteem and the differential prediction of aggression. J Pers Soc Psychol 82(5): 756-757.

- Kilpatrick DG (1992) Rape in America: A report to the nation. Technical Report.

- Center for Disease Control (2020) Violence Prevention: Sexual Violence.

- Ratnam D (2019) Delays in investigation, justice add to trauma of abuse victims.

- Bachman R (2000) A comparison of annual incidence rates and contextual characteristics of intimate-partner violence against women from the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) and the National Violence Against Women Survey (NVAWS). Violence Against Women 6(8): 839-867.

- Fernandez Y, Harris AJ, Hanson RK, Sparks J (2014) Stable-2007 coding manual revised 2012.

- Knight RA, Prentky RA (1990) Classifying sexual offenders. In Marshall WL, Laws DR, Barbaree HE (Eds.), Handbook of sexual assault, New York, USA, pp. 23-52.

- Eher R, Neuwirth W, Fruehwald S, Frottier P (2003) Sexualization and lifestyle impulsivity: clinically valid discriminators in sexual offenders. Int J of Offender Ther Comp Criminol 47(4): 452–567.

- Kanters T, Hornsveld RH, Nunes KL, Zwets AJ, Buck NM, et al. (2016). Aggression and social anxiety are associated with sexual offending against children. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health 15(3): 265-273.

- Bushman BJ, Baumeister RF (1998) Threatened egotism, narcissism, self-esteem, and direct and displaced aggression: Does self-love or self-hate lead to violence? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 75(1): 219.

- Twenge JM, Campbell WK (2003) Isn’t it fun to get the respect that we’re going to deserve? Narcissism, social rejection, and aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 29(2): 261-272.

- Ostrowsky MK (2010) Are violent people more likely to have low self-esteem or high self-esteem? Aggression and Violent Behavior 15(1): 69-75.

- Garofalo C, Holden CJ, Zeigler Hill V, Velotti P (2016) Understanding the connection between self‐esteem and aggression: The mediating role of emotion Aggress behav 42(1): 3-15.

- Gottfredson MR, Hirschi T (1990) A general theory of crime. Stanford University Press, USA, p. 316.

- Hanson RK, Morton Bourgon K (2004) Predictors of sexual recidivism: An updated meta-analysis. Public Safety Canada, USA.

- Knight RA, Thornton D (2007) Evaluating and improving risk assessment schemes for sexual recidivism: A long-term follow-up of convicted sexual offenders. Evaluating Risk Assessment Schemes.

- Mann RE, Hanson RK, Thornton D (2010) Assessing risk for sexual recidivism: Some proposals on the nature of psychologically meaningful risk factors. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment 22(2): 191-217.

- Kirby D (2002) The impact of schools and school programs upon adolescent sexual J sex res 39(1): 27-33.

- Somers CL, Gleason JH (2001) Does source of sex education predict adolescent sexual knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors? Education 121(4).

- Zelnik M, Kim YJ (1982) Sex education and its association with teenage sexual activity, pregnancy, and contraceptive use. Fam Plann Perspect 14(3): 117-126.

- Zabin LS, Hirsch MB, Smith EA, Streett R, Hardy JB (1986) Evaluation of a pregnancy prevention program for urban teenagers. Fam plann perspect 18(3): 119-126.

- Gallo A (2020) Treatment for non-contact sexual offenders: What we know and what we need. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity 27(1-2): 149-163.

- Gough HG (1974) A 24-Item version of the miller-fisk knowledge questionnaire. The J Psychol 87(2): 183-192.

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt EE (1995) Factor structure of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. J Clinic Psychol 51(6): 768-774.

- Ashenhurst JR, Harden KP, Corbin WR, Fromme K (2015) Trajectories of binge drinking, and personality change across emerging adulthood. Psychol Addict Behav 29(4): 978-991.

- Soldino V, Carbonell Vayá EJ, Seigfried Spellar KC (2019) Criminological differences between child pornography offenders arrested in Spain. Child Abuse Negl 98.

- Ryan T, Huss M, Scalora M (2017) Differentiating sexual offender type on measures of impulsivity and compulsivity. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity 24(1-2): 108-125.

- Thomaes S, Bushman BJ (2011) Mirror, mirror, on the wall, who’s the most aggressive of them all? Narcissism, self-esteem, and aggression. In Shaver PR, Mikulincer M (Eds.), Human aggression and violence: Causes, manifestations, and consequences Washington DC, American Psychological Association, pp. 203-219.

- Riggle ED, Rostosky SS (2011) A positive view of LGBTQ: Embracing identity and cultivating well-being. Rowman & Littlefield, p. 208.

- Abes ES, Jones SR (2004) Meaning-making capacity and the dynamics of lesbian college students’ multiple dimensions of identity. Journal of College Student Development 45(6): 612-632.

- Kelly GA (1955) The psychology of personal constructs. (1st edn), New York-Norton, USA.

- Crowder Meyer M, Gadarian SK, Trounstine J, Vue K (2020) A different kind of disadvantage: candidate race, cognitive complexity, and voter choice. Political Behavior 42(2): 509-530.

- Guzzo KB, Hayford S (2012) Race-ethnic differences in sexual health knowledge. Race Soc Probl 4(3-4): 158-170.

- Dehlendorf C, Rodriguez MI, Levy K, Borrero S, Steinauer J (2010) Disparities in family planning. Am J Obstet Gynecol 202: 214-220.

- Spinella M, Miley WM (2003) Impulsivity and academic achievement in college students. College Student Journal 37(4): 545.

- Walker JS, Bright JA (2009) False inflated self-esteem and violence: A systematic review and cognitive model. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology 20(1): 1-32.

© 2022 Brittanee Miller. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)