- Submissions

Full Text

Novel Research in Sciences

The Parekh-Berger Hierarchical Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis Model

Bina Parekh1* and Stephen E Berger2

1Professor and Associate Chair PsyD Clinical Psychology Program, The Chicago School of

Professional Psychology, USA

2Professor and Coordinator Forensic Concentration, The Chicago School of Professional

Psychology, USA

*Corresponding author: Bina Parekh, Professor and Associate Chair PsyD Clinical Psychology Program, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, USA

Submission: March 3, 2022;Published: March 29, 2022

.jpg)

Volume10 Issue4March, 2022

Abstract

Traditionally, there have been two general approaches to analyzing data from a research study. One approach is quantitative in which participants receive scores of a quantitative nature. When those scores meet the criteria of an interval scale, the data are analyzed with parametric statistics. When the scores are not deemed to reflect at least an interval scale, the scores are analyzed with non-parametric techniques. Alternatively, participants engage in an interview rather than obtain scores on a scale or through a performance task. In the case of individual interviews, the transcripts are then analyzed with a qualitative technique [1]. One such approach, named Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA), was developed by Smith JA [2,3]. In Smith’s IPA, themes are extracted and applied back to the interviewed participants. Thus, Smith has primarily utilized an idiographic application of IPA. The current authors have developed an approach to IPA that makes it highly amenable to a nomothetic application. The Parekh-Berger Hierarchical IPA (HIPA) Model incorporates interrater reliability and extends the Specific Themes extracted from the interviews to Higher Order Themes, and a format has been developed to extend the Higher Order Themes to Superordinate Themes-where appropriate. In addition, a concept of Universal Specific Themes has also been developed as those Themes help extend IPA to a nomothetic application. This report provides a review of IPA and then details the Parekh-Berger HIPA Model. Specific examples of some results from the Parekh-Berger Model are provided as well a step by step approach to utilizing the Model as well as reporting the results of the HIPA Model .

Introduction

Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) is a qualitative approach that allows

researchers to understand and examine the ‘lived experiences’ of participants [4]. Smith et al

developed IPA to capture the personal meaning and narratives that often are not adequately

addressed with more quantitative forms of analysis [5]. IPA gives depth to understanding the

human condition by allowing participants to explain their experiences in their own voice.

It has been routinely found that IPA is an excellent method to examine constructs found

within clinical psychology [5]. The domain of clinical psychology consists of addressing the

emotional, psychological, behavioral, and intellectual adjustments of populations across the

lifespan [6]. Much of clinical psychology research is focused on aggregating large amounts

of quantitative data to understand people’s growth and development. In contrast, IPA is

distinctive because it emphasizes the importance of finding common meaning across fewer

participants by examining their rich personal expressions [7].

While there are a number of qualitative approaches available, the current authors have

found that the IPA approach developed by Smith has produced very valuable results when

analyzing the narratives of participants with unique ‘lived experiences [2]. The ability to

aggregate and develop thematic content that shows trends in participants’ experiences makes

it a particularly applicable methodological approach to those students conducting clinical

psychology dissertations. As Smith highlighted, it is extremely important for the researcher to provide the conditions for the participants to feel safe and

comfortable to share their stories [5]. Clinical psychology graduate

students are ideal researchers to implement IPA approaches since

they are taught methods for establishing rapport with others using

verbal and nonverbal techniques.

Because of the synchrony between IPA and clinical psychology,

the current authors have routinely used IPA with clinical

psychology dissertations, which has aided our development of

a hierarchical approach to IPA. The current authors have made

several modifications to the original IPA methodology that will be

discussed in this paper. The authors believe that these modifications

are particularly helpful when applied to understanding clinical

psychology phenomenon, as they lend themselves to providing a

more holistic and inclusive narration of participants’ experiences.

Allowing participants to share their stories on their own terms

through a semi-structured interview can reveal important nuanced

information that a quantitative study simply cannot replicate.

The Traditional IPA

Smith developed Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis

(IPA) to understand the participant responses in a single case

design or involving several participants [2]. Traditionally IPA can

be quite labor intensive, as it involves multiple steps of analysis

[5]. According to Smith JA et al. [8] their methodology is not strict

or inflexible, but rather it can be adjusted to suit the researcher’s

empirical style and end goals [8]. It should be duly noted that all

semi-structured interviews need to be transcribed for ease of

analysis. The following is a description of the stages involved in

conducting a traditional IPA.

The first stage is comprised of reading the transcripts several

times in order to become familiar with the transcript content.

Additionally, as the researcher becomes more familiar with the

content, they can make comments in the left-side margins [8].

There are no explicit rules or requirements for making these types

of comments and are based solely on the researcher’s impressions

and observations [9]. In the second stage of IPA, the researcher

rereads the transcripts and now begins to examine the information

in terms of emergent themes, which are denoted on the right-hand

margin [8]. This is perhaps the most challenging and crucial stage

of analysis. In some instances, it may be easy to provide names and

identifiers for themes (Specific Themes), yet in other cases it may

require considerable interactions with the transcripts for Specific

Themes to emerge from the text [9]. The key to this phase of

analysis is developing themes that allow for connections across all

participants but also maintains the uniqueness of each participant’s

expression [8].

In the third stage of the IPA, the researcher begins to cluster the

individual Specific Themes to capture theoretical or experiential

similarities. These thematic clusters are then assembled into Higher

Order Themes, which should comprehensively represent content

across all participants. 8,9 In the final stage, the Higher Order

Themes are written up highlighting the narratives of participants

[9]. By identifying the overlaps between general themes to create

a Higher Order Theme, IPA allows for theoretical unification, while

preserving the unique ‘lived experience [8].

The Parekh-Berger Hierarchical Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (HIPA) Model

The first modification in the Parekh-Berger model is that the

researcher does not read and reread every transcript. In some

instances, rereading part or even the entire transcript might

be done. In addition, the laborious process of note taking is not

deemed necessary. Instead, the researcher relies upon their first

impression-their own interpretive perspective as to possible

Specific Themes and notes those. This simplified process has turned

out to be sufficient for the generation of an initial list of possible

Specific Themes.

Another distinctive adaptation that the current authors have

made to traditional IPA is the utilization of interrater reliability.

It is imperative that IPA research has tools to evaluate and denote

the authenticity of its results [4]. Often, authentication involves

having participants review the actual transcripts for accuracy or

triangulating data among different methods or various stakeholders

[4]. The current authors have applied the statistical concept of

interrater reliability as a method to solidify the genuineness

of themes found across transcripts [10]. Interrater reliability

essentially examines if data collectors who examine the same

situation or phenomenon will record the same observations [10].

Thus, data collectors with higher degree of agreement will have

a higher interrater reliability. The current authors are proposing

two methods of using interrater reliability to examine consistency

in terms of themes: Blind Review and Independent Check Review.

In Blind Review, researchers give another reviewer the participant

transcripts and ask them to go through each transcript and

denote individual Specific Themes. In this method, it is important

to examine if the second evaluator, who is blind to the proposed

Specific Themes of the first reader, will find similar Specific Themes

in the transcript. The level of agreement between reviewer 1 and

reviewer 2 is calculated using an interrater reliability analysis.

Unfortunately, this method can be very time intensive and requires

a significant commitment on the part of the second reviewer.

Another method that is not as cumbersome to implement

is the Independent Check Review. In this method, the second

reviewer receives a list of proposed Specific Themes found in the

transcripts by the first reader. The second reviewer is to denote the

frequencies or number of times they find a specific theme across

the transcripts. The first reviewer has also conducted a frequency

count of their proposed Specific Themes; however, the second

reviewer is not privy to that information and must evaluate the

frequencies blindly/independently. Finally, the second reviewer’s

frequency count is compared to the first reviewer’s frequency

count to determine if there is agreement across both reviewers.

This method is less difficult to implement and still provides a solid

assessment of interrater reliability. The current authors believe that these two methods are essential to bolstering the consistency

of IPA designs. It is readily apparent that researcher’s individual

training, experiences, and possibly biases may impact the review

of transcripts. The current authors believe that reliability checks

are a method by which to enhance the empirical robustness of IPA

designs.

Higher Order Themes

In the traditional IPA, the task after the Specific Themes have been delineated is to group them together into clusters. The clusters are thought of as Higher Order Themes. An analogy can be made to Factor Analysis. In a Factor Analysis, participants receive scores on a number of measures. Then, through correlational techniques, various of the measures (or scales) are found to be related to each other and not to other scales (or groupings of scales). Thus, these correlated measures are grouped together under the label: Factor. Because these are all quantitative relationships, it is possible to determine the amount of variance among the scores is accounted for by each Factor. It is our perspective that IPA can be thought of as a non-quantitative factor analysis. The Specific Themes can be thought of as non-quantitative measures. Through logical and conceptual analysis, the researcher groups Specific Themes together and gives a name to that grouping that captures/reflects the Specific Themes that the researcher determines have a common relationship with each other. These groupings or clusters of Specific Themes are considered to be Higher Order Themes. An example of a similar concept can be found with the Wechsler Intelligence Scales. There are individual measures (e.g., Coding and Symbol Search). These are found to correlate with each other and are grouped together under a Higher Order concept called: Processing Speed. In IPA, the goal is to determine if there are Specific Themes that can be grouped together in Higher Order Themes that “tell the story” of what emerges across all of the interviews. Finally, in traditional IPA, the final task with the Higher Order Themes is to see if they can be arranged in a numbered order such that the names of the Higher Order Themes is a short-hand expression of the story that the participants have shared about their phenomenological experience has been of the life events being investigated. An example of this is provided at the end of the next section of this report.

Universal Specific Themes

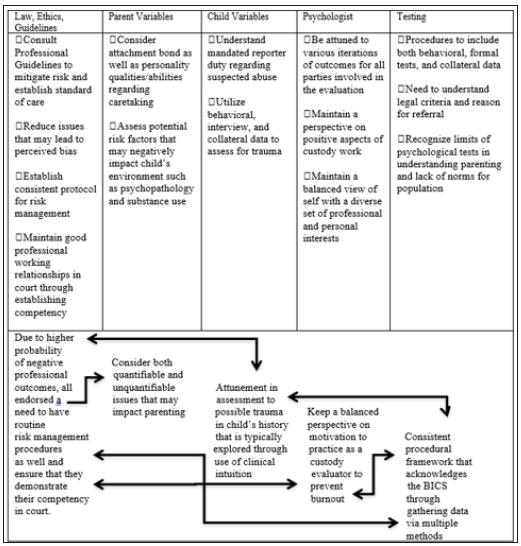

Figure 1: Pictorial Representation and Narrative of Universal Themes.

Another of the major modifications to Smith’s IPA approach is that we examine for Specific Themes that are expressed by every participant. We term these as Universal Specific Themes. It turns out that it is not a coincidence when every participant expresses the same Specific Theme in their separate and independent interviews. It is not that the interviewer probes for such Themes. They get expressed spontaneously during the course of each and every interview. We have found that when these Universal Specific Themes occur, they tell the story that emerges across the interviews of the experience that the participants have had in regard to the matter being investigated. Below, we provide a Figure from the dissertation of Ortega C et al. [11]. Psychologists who conduct child custody evaluations on referral from the Family Law Court were asked to share their experience of conducting such evaluations. Figure 1 clearly shows how Universal Specific Themes provide a short-hand version of the story that the Higher Order Themes reveal. As can be seen, across the psychologists, the story that emerged was that one has to start from a legal, ethical approach and then progress to addressing parent variables, then child variables, and then the psychologist her or himself is a variable in the mix with psychological testing factors having to be taken into account to complete the evaluation. As the bottom of the Figure show, these are not discrete steps, but each factor influences the others in the sensitive matter of child custody evaluations.

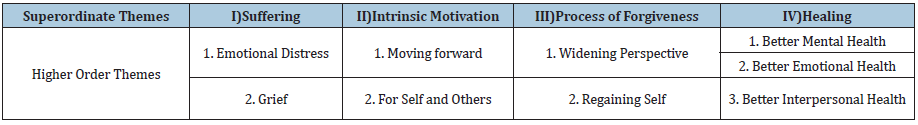

Superordinate Higher Order Themes

In a recent study, we had the experience of discovering that it is even possible to have Superordinate Higher Themes that subsume the Higher Order Themes that are extracted from the interviews [12]. In this study of women and men who had been sexually abused, and who reported that they had forgiven their abuser. In this study of the forgiveness process, a number of Higher Order Themes were extracted. Upon further analysis, it was determined that the Higher Order Themes themselves could be further grouped in a Hierarchy that contained the Higher Order Themes and their included Specific Themes. What also stood out was that the Superordinate Higher Order Themes turned out to reflect the model that had been proposed for how such forgiveness could occur psychologically. Table 1 presents the Superordinate Themes and the Higher Order Themes subsumed within them.

Steps in the Parekh-Berger Hierarchical Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis Model

The Parekh-Berger HIPA Model begins in the traditional manner. A determination is made of a psychological phenomenon of interest. The researcher defines a population for whom that phenomenon is relevant. Then, through sampling processes, participants are sought who agree to participate in a semi-structured interview. Using predetermined, mostly open-ended questions, the interviewer seeks to facilitate the participant expressing in their own words what their life experience has been like and what it has meant to them.

When the interviews are completed, the researcher reads and

reviews the transcripts and attempts to get a sense from each of the

transcripts what are the unique, individual themes that seem to be

expressed by the participant. The reviewer is attempting to identify

the individual pieces (Specific Themes) that are being expressed

by each participant. The reviewer is attempting to specify the

elements of the participant’s internal representations of what they

experienced-the phenomenology of the participant’s experience.

Once the first reader (reviewer) has extracted all of the possible

Specific Themes that they can identify (whether it is from one

reading of each transcript or several readings of any or all of the

transcripts), a second reader/reviewer is now involved. A decision

is made as to whether this reviewer will use the Blind Review

method of attaining an interrater reliability or the Independent

Check Review method. Accordingly, a final list of Specific Themes

is created that are not just the product of one person’s perceptions

of the interviews, but that there is some degree of independent

assessment and concordance regarding the Specific Themes that

appear to have been expressed by at least two participants and

recognized by two independent reviewers. Each Specific Theme is

now given a final official name. The Specific Themes are numbered

in the accordance with the sequence in which they were identified

in the transcripts.

Now comes the task of creating Higher Order Themes. Again,

the Parekh-Berger HIPA Model involves at least two researchers. In

the case of dissertations, the Chair of the Dissertation Committee

and the student then make an effort to group the Specific Themes

into Clusters that are called Higher Order Themes and given names

that are to reflect the concept that the Specific Themes have in

common. In other types of studies, the lead researcher enlists the

involvement of another researcher in the determination of Higher

Order Themes. It should be understood that the names of the Higher

Order Themes are an abstraction representing, in some sense, more

of the phenomenological experience of the participants that reflects

a conceptualization of the individual themes that cluster together.

The next step in the Parekh-Berger HIPA Model is to determine

an ordering of the Higher Order Themes. We have found that almost

invariably, the Higher Order Themes can be placed in a numbered

order such that their names basically tell the “story” that emerges

across the interviews that reflects the common, phenomenological

experiences of the participants, in a sort of short-hand way. Finally,

an examination if made of the Specific Themes of those that were

expressed by every participant. These Specific Themes are named:

Universal Specific Themes. Again, we have found that these

Universal Specific Themes also tell the story, in greater specificity

than the reading of the Higher Order Themes, yet less specificity

than the entirety of all of the Specific Themes. This process can be

seen in Figure 1.

Finally, it may be possible that even the Higher Order Themes

can be grouped into clusters that tell the story expressed by the participants. These types of themes are called Superordinate

Higher Order Themes. We have not found this to be common in the

several dozen HIPA studies of which we are aware. However, one

recent example emerged and can be seen in Table 1.

Our method for reporting the results of the Parekh-Berger HIPA

Model is to first present the list of Specific

Themes that has emerged retaining their sequential number

as part of their identification. Next, we present a Table showing

the Higher Order Themes in their numbered order with their

constituent Specific Themes listed under them. If Universal Specific

Themes are found that help delineate the story, then a chart or

Figure is constructed and presented at that point such as is seen

in Figure 1. Next, if Superordinate Higher Order Themes are

created, those are then presented in a Table or Chart such as is

seen in Table 1. Finally, the Results section of a report will present

specific quotes from the transcripts that illustrate the Specific

Themes and therefore the bases for which the various Higher Order

Themes were created. Thus these Tables or Charts are organized

and presented for each Higher Order Theme, one at a time, with

quotes for each of the Specific Themes that constitute that Higher

Order Theme. Now comes the task of creating a Discussion section

to explain and expand upon the perspectives gained from this

hierarchical ordering of Specific Themes, Higher Order Themes,

possible Universal Specific Themes and Superordinate Themes.

Reporting the Final Perspectives of the Study

The most traditional method for reporting the results and

conclusions from a study is to create a journal article with

introduction, methods, results and discussion section. Often,

that model suffices for reporting statistical tests and presenting

interpretations and discussing the results. Often, the traditional

method also works well for reporting IPA results for traditional

IPAs as well as for the Parekh-Berger HIPA Model. However, we have

found that the traditional journal format does not always do justice

to the wealth of personal experience that is revealed through IPA

methodology.

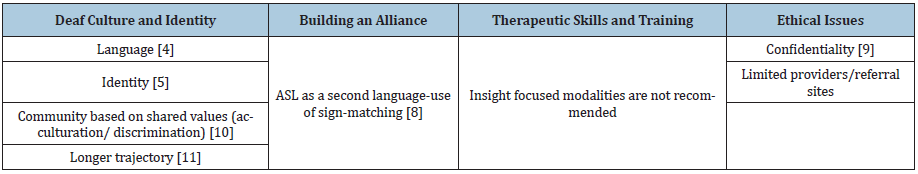

As an example that we can offer is the dissertation of our

former student, Tucker M et al. [13]. She interviewed therapists

who conducted psychotherapy using sign language with hearing

impaired patients. It was determined that the experiences of these

therapists would not be properly shared by a traditional journal

article. It was agreed that much more detail and information needed

to be reported. Consequently, a e-book was created. Presented

below is the Table from her dissertation (her Table 1, our Table 2)

that depicts the Higher Order Themes that were created with their

constituent Specific Themes.

Table 1: Superordinate themes and concomitant higher order themes that reflect the forgiveness process experienced by women and men who were sexually abused and report having forgiven their abuser.

Table 2: Higher order themes and component universal specific themes.

Note: The number of the universal specific themes is presented in brackets.

Summary and Conclusion

We have presented a model for conducting Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis that we have been using for a number of studies. The model from which we have worked is based on the methods developed by Smith JA [2]. We have termed our approach the Parekh-Berger Hierarchical Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis Model (HIPA). We and our colleagues have utilized the HIPA model in dozens of studies. Our Model has been applied in a nomothetic method. Consequently, we have relied upon having interrater reliabilities so that the resultant themes are not just a reflection of one person’s perspective of the “story” that emerges from the analyses of the interviews. In this article, we have provided the rationale for the HIPA model, delineated the steps in extracting themes from the interviews of participants and provided a guide as to how to report the results and interpretations of the resultant themes. We have also provided examples of what such results are best presented. It should be noted that by providing the list of the Specific Themes and the resultant Higher Order Themes along with specific quotes from the transcripts, readers are well able to create their own phenomenological interpretations of the presented results.

References

- Willig C (2001) Qualitative research design. Introducing qualitative research in psychology: Adventures in theory and method. Open University Press, Buckingham, UK.

- Smith JA (1996) Beyond the divide between cognition and discourse: Using interpretative phenomenological analysis in health psychology. Psychology and Health 11(2): 261-271.

- Smith JA (2004) Reflecting on the development of interpretative phenomenological analysis and its contribution to qualitative research in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 1(1): 39-54.

- Alase A (2017) The Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA): A guide to a good qualitative research approach. International Journal of Education & Literacy Studies 5(2): 9-19.

- Smith JA, Flowers P, Larkin M (2009) Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research. (2nd edn), Sage Publications, California, USA.

- American Psychological Association (2008) Clinical Psychology. American Psychological Association, Washington DC, USA.

- Creswell JW (2003) Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed approaches, Sage Publications, California, USA.

- Smith JA, Osborn M (2003) Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In: Smith JA (Eds.), Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Methods, Sage Publications, London, UK, pp. 51-80.

- Fade S (2004) Using interpretative phenomenological analysis for public health nutrition dietetic research: A practical guide. Proc Nutr Soc 63(4): 647-653.

- McHugh ML (2012) Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica (Zagreb) 22(3): 276-282.

- Ortega C, Berger SE (2016) Qualitative analysis of child custody evaluation practices. International Journal of Psychological and Behavioral Sciences 10(6): 2126-2137.

- You M, MacMillin M, Berger SE (2022) Intrinsic motivation, The process of forgiveness, and the effect of forgiveness on healing for sexual abuse survivors.

- Tucker M, Berger SE, Parekh B (2020) A phenomenological examination of the hearing therapist-deaf patient dyad: Barriers, language, culture, and training, e-book. Journal of Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Iris Publishers, California, USA, pp. 1-38.

© 2022 Bina Parekh. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)